This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Karachays or Karachai (Karachay-Balkar: Къарачайлыла, romanized: Qaraçaylıla or таулула, romanized: tawlula, lit. 'Mountaineers')[3] are an indigenous[4] North Caucasian-Turkic ethnic group native to the North Caucasus. They are primarily located in their ancestral lands in Karachay–Cherkess Republic, a republic of Russia in the North Caucasus. They have a common origin, culture, and language with the Balkars.[5]

Къарачайлыла | |

|---|---|

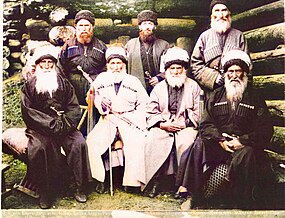

Karachay men in the 19th century | |

| Total population | |

| c. 250,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 226,271 205,578[1] | |

| 20,000[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Karachay, Kabardian, Russian, Turkish (diaspora) | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Balkars, Nogais, Kumyks, Circassians, Abazins, North Caucasian peoples | |

History

editAccording to Balkar historian, ethnographer and archaeologist Ismail Miziev who was a specialist in the field of North Caucasian studies, the theories on the origins of the Karachays and the neighboring Balkars is among "one of the most difficult problems in Caucasian studies," [6] due to the fact that they are "a Turk-speaking people occupying the most Alpine regions of Central Caucasus, living in an environment of Caucasian and Iranian (Ossetian) languages."[6] Many scientists and historians have made attempts to study the issue, but "the complexity of a problem lead to numerous hypotheses, often contradicting each other." He concluded that "Balkarians and Karachais are among the most ancient nationalities of Caucasus. The roots of their history and culture are intimately intertwined with the history and culture of many Caucasian peoples, as well as numerous Turk nationalities, from Yakutia to Turkey, from Azerbaijan to Tatarstan, from the Kumik and Nogai to the Altai and Hakass."[6]

Ankara University's professor Ufuk Tavkul, another specialist, locates that the ethnogenesis of Karachays-Balkars and Kumyks inside the Caucasus, not outside;[7] he then succinctly describes the ethnogenesis of peoples of the Caucasus, including the Karachays and Balkars, thus:

In the first millennium before Christ diverse groups representing the ancestors of the Abkhaz/Adyghe, Ossetian and Karachay-Balkar people lived in the Caucasus, who contributed to varying degrees to the emergence of these peoples. From the 7th century BC Kimmerian, Scythian, Sarmatian, Alan, Hun, Bulghar Turk, Avar, Khazar, Pecheneg, Kipchak, etc. groups invaded the Caucasus and settled there, causing a radical change in the ethnic map of the Central Caucasus.

By assimilating the local Caucasian people of Caucasid anthropological features who had brought to life the Koban culture of the Bronze Age, the Ossetians of an Iranian tongue and the Turkic-speaking Karachay-Balkars emerged in the Middle Caucasus. The Ossetian and Karachay-Balkar people and cultures were certainly fundamentally influenced by the Caucasian substratum belonging to the Koban culture (Betrozov 2009: 227)— "About Karachay-Balkar people: Ethnogenesis", in Sipos & Tavkul (2015), Karachay-Balkar folksongs, p. 44.[8]

Other research by Boulygina et al. (2020) shows Karachays' genetic connection to the pre-historic Koban culture.[9] A recent genetic study states the following: "Balkars and Karachays belong to the Caucasian anthropological type. According to the results of craniology, somatology, odontology, and dermatoglyphics, the native (Caucasian) origin of the Balkars and Karachays and their kinship with the representatives of neighboring ethnic groups and a minor role of the Central Asian component in their ethnogenesis were concluded."[10]

The state of Alania was established prior to the Mongol invasions and had its capital in Maghas, which some authors locate in Arkhyz, the mountains currently inhabited by the Karachay, while others place it in either what is now modern Ingushetia or North Ossetia. In the 14th century, Alania was destroyed by Timur and the decimated population dispersed into the mountains.

In the nineteenth century Russia took over the area during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. On October 20, 1828 the Battle of Khasauka took place, in which the Russian troops were under the command of General Georgy Emanuel. The day after the battle, as Russian troops were approaching the aul of Kart-Dzhurt, the Karachay elders met with the Russian leaders and an agreement was reached for the inclusion of the Karachay into the Russian Empire.[citation needed]

After annexation, the self-government of Karachay was left intact, including its officials and courts. Interactions with neighboring Muslim peoples continued to take place based on both folk customs and Sharia law. In Karachay, soldiers were taken from Karachai Amanat, pledged an oath of loyalty, and were assigned arms.[citation needed]

From 1831 to 1860, the Karachays were divided. A large portion of Karachays joined the anti-Russian struggles carried out by the North Caucasian peoples; while another significant portion of Karachays, due to being encouraged by the Volga Tatars and Bashkirs, another fellow Turkic Muslim peoples that have long loyal to Russia, voluntarily cooperated with Russian authorities in the Caucasian War. [citation needed] Between 1861 and 1880, to escape reprisals by the Russian army, some Karachays migrated to the Ottoman Empire although most Karachays remain in modern territory.[11] [need quotation to verify]

All Karachay officials were purged by early 1938, and the entire nation was administered by NKVD officers, none of whom were Karachay. In addition, the entire intelligentsia, all rural officials and at least 8,000 ordinary farmers were arrested, including 875 women. Most were executed, but many were sent to prison camps throughout the Caucasus.[12]

During the parade of sovereignties and the collapse of the USSR on November 30, 1990, KCHAO withdrew from the Stavropol Territory and became the Karachay-Cherkess Soviet Socialist Republic (KChSSR) as part of the RSFSR, which was approved by a resolution of the Supreme Council of the RSFSR on July 3, 1991.

In 1989–1997, the Karachay national movements appealed to the leadership of the RSFSR with a request to restore a separate autonomy of Karachay.[13]

On November 18, 1990, at the congress of Karachay deputies of all levels, the Karachay Soviet Socialist Republic (since October 17, 1991 — the Karachay Republic)[14][15] was proclaimed as part of the RSFSR, which was not recognized by the leadership of the RSFSR. On March 28, 1992, a referendum was held in which, according to the official results, the majority of the population of Karachay-Cherkessia opposed the division. The division was not legalized, and a single Karachay-Cherkessia remained.

Deportation

editIn 1942 the Germans permitted the establishment of a Karachay National Committee to administer their "autonomous region"; the Karachays were also allowed to form their own police force and establish a brigade that was to fight with the Wehrmacht.[16] This relationship with Nazi Germany resulted, when the Russians regained control of the region in November 1943, with the Karachays being charged with collaboration with Nazi Germany and deported.[17] Originally restricted only to family members of rebel bandits during World War II, the deportation was later expanded to include the entire Karachay ethnic group. The Soviet government refused to acknowledge that 20,000 Karachays served in the Red Army, greatly outnumbering the 3,000 estimated to have collaborated with the German soldiers.[12] Karachays were forcibly deported and resettled in Central Asia, mostly in Kazakhstan and Kirghizia.[18] In the first two years of the deportations, disease and famine caused the death of 35% of the population; of 28,000 children, 78%, or almost 22,000 perished.[19]

Diaspora

editAbout 10,000–15,756 Karachays and Balkars emigrated to the Ottoman Empire, with their migration reaching peaks in 1884–87, 1893, and 1905–06.[20]

Karachays were also forcibly displaced to the Central Asian republics of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kirghizia during Joseph Stalin's relocation campaign in 1944. Since the Nikita Khrushchev era in the Soviet Union, the majority of Karachays have been repatriated to their homeland from Central Asia. Today, there are sizable Karachay communities in Turkey (centered on Afyonkarahisar), Uzbekistan, the United States, and Germany.

Geography

editThe Karachay nation, along with the Balkars occupy the valleys and foothills of the Central Caucasus in the river valleys of the Kuban, Big Zelenchuk River, Malka, Baksan, Cherek, and others.

The Karachays are very proud of the symbol of their nation, Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe, with an altitude of 5,642 meters.

Culture

editLike other peoples in the mountainous Caucasus, the relative isolation of the Karachay allowed them to develop their particular cultural practices, despite general accommodation with surrounding groups.[21]

Karachay people live in communities that are divided into families and clans (tukums). A tukum is based on a family's lineage and there are roughly thirty-two Karachay tukums. Prominent tukums include: Abayhan, Aci, Batcha (Batca), Baychora, Bayrimuk (Bayramuk), Bostan, Catto (Jatto), Cosar (Çese), Duda, Hubey (Hubi), Karabash, Kochkar, Laypan, Lepshoq, Ozden (Uzden), Silpagar, Tebu, Teke, Toturkul, Urus.[citation needed]

Language

editKarachays speak the Karachay-Balkar language, which comes from the northwestern branch of Turkic languages. The Kumyks, who live in northeast Dagestan, speak a closely related language, the Kumyk language.

Religion

editThe majority of the Karachay are followers of Islam.[22] Some Karachays began adopting Islam in the 17th and 18th centuries due to contact with the Nogais, the Crimean Tatars, and most significantly, the Circassians.[23][24] The Sufi Qadiriya order has a presence in the region.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Russian Census of 2021". (in Russian)

- ^ – Malkar Türkleri Archived October 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peter B. Golden (2010). Turks and Khazars: Origins, Institutions, and Interactions in Pre-Mongol Eurasia. p. 33.

- ^ Szczśniak, Andrew L. (1963). "A Brief Index of Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Asiatic Russia". Anthropological Linguistics. 5 (6): 1–29. ISSN 0003-5483. JSTOR 30022425.

- ^ "КАРАЧАЕВЦЫ • Большая российская энциклопедия – электронная версия". old.bigenc.ru. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ a b c Miziev, Ismail (1994). The History of the Karachai-Balkarian People. Translated by P.B Ivanov. Nalchik: Mingi-Tau Publishing (Elbrus).

- ^ Sipos & Tavkul (2015), p. 42.

- ^ Sipos & Tavkul (2015), p. 44.

- ^ Boulygina, Eugenia; Tsygankova, Svetlana; Sharko, Fedor; Slobodova, Natalia; Gruzdeva, Natalia; Rastorguev, Sergey; Belinsky, Andrej; Härke, Heinrich; Kadieva, Anna; Demidenko, Sergej; Shvedchikova, Tatiana; Dobrovolskaya, Maria; Reshetova, Irina; Korobov, Dmitry; Nedoluzhko, Artem (2020-06-01). "Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome diversity of the prehistoric Koban culture of the North Caucasus". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 31: 102357. Bibcode:2020JArSR..31j2357B. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102357. ISSN 2352-409X. S2CID 218789467.

G2a Y-haplogroup which is frequent in modern Ossetians, Balkars, and Karachays was found in Koban culture

- ^ Dzhaubermezov, M. A.; Ekomasova, N. V.; Reidla, M.; Litvinov, S. S.; Gabidullina, L. R.; Villems, R.; Khusnutdinova, E. K. (January 2019). "Genetic Characterization of Balkars and Karachays Using mtDNA Data". Russian Journal of Genetics. 55 (1): 114–123. doi:10.1134/s1022795419010058. ISSN 1022-7954. S2CID 115153250.

- ^ Толстов В. (1900). История Хопёрского полка, Кубанского казачьего войска. 1696—1896. В 2-х частях. Т. 1. Тифлис. pp. 205–209.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Comins-Richmond, Walter (September 2002). "The deportation of the Karachays". Journal of Genocide Research. 4 (3): 431–439. doi:10.1080/14623520220151998. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 71183042.

- ^ Мякшев А. П. (2014). "Национальные движения депортированных народов как один из факторов распада союза ССР". Известия Саратовского Университета. Новая Серия. Серия История. Международные Отношения. 14 (4) (Известия Саратовского университета. Новая серия. Серия История. Международные отношения ed.): 40–46.

- ^ Тетуев А. И. (2016). "Особенности этнополитических процессов на Северном Кавказе в период системной трансформации российского общества (на материалах Кабардино-Балкарии и Карачаево-Черкесии)". Oriental Studies (1) (Вестник Калмыцкого института гуманитарных исследований РАН ed.): 90–98.

- ^ Смирнова Я. С. (1992). "Карачаево-Черкесия: этнополитическая и этнокультурная ситуация" (Исследования по прикладной и неотложной этнологии ed.). ИЭА РАН. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-11.

- ^ Norman Rich: Hitler's War Aims. The Establishment of the New Order, page 391.

- ^ In general, see Pohl, J. Otto (1999). Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30921-2.

- ^ Pohl lists 69,267 as being deported (Pohl 1999, p. 77); while Tishkov says 68,327 citing Bugai, Nikoli F. (1994) Repressirovannie narody Rossii: Chechentsy i Ingushy citing Beria, (Tishkov, Valery (2004). Chechnya: Life in a War-Torn Society. University of California Press. p. 25.); and Kreindler says 73,737 (Kreindler, Isabelle (1986). "The Soviet Deported Nationalities: A summary and an update". Soviet Studies. 38 (3): 387–405. doi:10.1080/09668138608411648.).

- ^ Grannes, Alf (1991). "The Soviet deportation in 1943 of the Karachays: a Turkic Muslim people of North Caucasus". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 12 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/02666959108716187.

- ^ Hamed-Troyansky 2024, p. 49.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2008). The Northwest Caucasus: Past, Present, Future. Central Asian studies series, 12. London: Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-415-77615-8.

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey E. (2011-05-25). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-59884-303-3.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin (1986). Islamic Peoples Of The Soviet Union. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-136-14266-6.

- ^ a b Bennigsen, Alexandre; Wimbush, S. Enders (1986). Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. Indiana University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-253-33958-4.

Further reading

edit- Hamed-Troyansky, Vladimir (2024). Empire of Refugees: North Caucasian Muslims and the Late Ottoman State. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-3696-5.

- Pohl, J. Otto (1999), Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949, Greenwood, ISBN 0-313-30921-3

- Sipos, János; Tavkul, Ufuk (2015). Karachay-Balkar folksongs (PDF). Translated by Pokoly, Judit. Budapest: L'Harmattan.