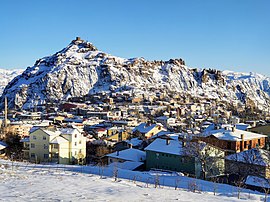

Şebinkarahisar is a town in Giresun Province in the Black Sea region of northeastern Turkey. It is the administrative seat of Şebinkarahisar District.[2] Its population is 10,695 (2022).[1]

Şebinkarahisar

Nikopolis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 40°17′19″N 38°25′24″E / 40.28861°N 38.42333°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Giresun |

| District | Şebinkarahisar |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ömer Şentürk (AKP) |

| Elevation | 1,364 m (4,475 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 10,695 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 28400 |

| Area code | 0454 |

| Climate | Csb |

| Website | www |

Name

editThe 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius writes that the Roman general Pompey captured the then ancient fortress and renamed it Colonia, in Greek Koloneia (Κολώνεια).[3] A Greek inscription of the ninth or tenth century found in the fortress securely identifies Şebinkarahisar with Koloneia. Curiously, the Seljuk historian Ibn Bibi and 14th-century coins minted by the Eretnids record an Armenian variation of the name, Koğoniya.[4] The historical Turkish form of this name was Kuğuniya.[5]

In the 11th century, a second name becomes associated with the place: the town retains the name Koloneia but the fortress above is called Mavrokastron, Greek for "Black Fortress". The Turkish toponym Karahisar (Greek: Γαράσαρη, actual Turkish name of the district: Gareysar), appearing first in the 14th century, is a translation of Mavrokastron.[6] The town was later called Şapkarahisar ("Black Fortress of Alum") or Kara Hisar-ı Şarkî/Şarkî Kara Hisar ("Black Fortress of the East"). The place has been known as Şebinkarahisar since the 19th century and both names were used. On 11 October 1924 Mustafa Kemal visited this town and proposed that the name Şebin Karahisar be used. In 1890, the geographical historian W. M. Ramsay indicated that the Armenians still call this city Nikopoli (from Greek Νικόπολη);[7] so do the Pontic Greeks to this day.[8] It should not be confused with the nearby Koyulhisar, where the ruins of ancient Roman Nikopoli lie.[9][better source needed]

History

editThe recorded history of Şebinkarahisar begins with the Third Mithridatic War. After the defeat of Mithridates VI, Pompey strengthened the town's fortifications and founded a Roman colony (colonia).

In the Byzantine period, the city was rebuilt by Justinian I (r. 527–565). In the 7th century, it became part of the Armeniac Theme, and later of Chaldia, before finally becoming the seat of a separate theme by 863. It was attacked by Arab raids in 778 and in 940.[10]

Şebinkarahisar fell to the Seljuk Turks soon after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. It remained in Turkish hands since, with the exception of a short-lived Byzantine recovery ca. 1106.[10] Through the following centuries, the fortress occupied a strategic position on the frontier between the Turkish-controlled interior and the Empire of Trebizond. The Danishmends held the fortress until the 1170s, when it passed into the hands of the Saltukids of Erzurum. In 1201/1202 the Mengujekids, vassals of the Seljuks of Rum, took over. Following the Mongol invasion of the mid-13th century, the fortress was under command of the Eretnids, who minted coins in the town. A succession of petty Turkmen warlords controlled the town until Uzun Hasan of the Ak Koyunlu took over in 1459, perhaps believing that the place constituted part of the dowry of his new Greek wife, the daughter of John IV of Trebizond.[11]

Mehmed II took the town for the Ottomans from Ak Koyunlu in 1461,[12] and consolidated his rule over the area in 1473 following his defeat of Uzun Hasan at the Battle of Otluk Beli. From Şebinkarahisar he sent a series of letters announcing his victory, including an unusual missive in the Uyghur language addressed to the Turkmen of Anatolia.[13] A careful survey of the fortifications above the town has revealed that the Ottomans invested heavily in repairs to the original Late Antique-Byzantine-Seljuk walls and, in addition, constructed an impressive “citadel complex” at the summit.[14] It became a sanjak centre as "Karahisar-I Şarki", initially in Rum Eyalet (1473-1514 and again 1520-1555), Bayburt Eyalet (1514-1516), Diyarbekir Eyalet (1516-1520), Erzurum Eyalet (1555-1805), Trabzon Eyalet (1805-1865) and Sivas Vilayet (1865-1923).

According to the Ottoman General Census of 1881/82-1893, the kaza of Şebinkarahisar (Karahisar-i Şarki) had a total population of 35.051, consisting of 19.421 Muslims, 8.512 Greeks and 7.118 Armenians.[15]

The Shabin-Karahisar uprising

editŞebinkarahisar was one of the few locations where Armenians actively resisted the Armenian genocide.[16][17]

As news of deportations and massacres in other parts of the Ottoman Empire reached the town, its Armenian population decided to make preparations for self-defence. On June 15, 1915 some 300 Armenians, mostly wealthy merchants, were arrested. On the following day, after further attempted arrests, fighting erupted and barricades were erected in the town's Armenian districts. By June 18 most of those districts had fallen or been abandoned. Some 5,000 Armenians from the town and nearby villages, 75% of them women and children, retreated into Şebinkarahisar's medieval fortress. It was then surrounded by Turkish troops, who directed heavy artillery at its walls. On the night of July 11, with food, water, and ammunition almost exhausted, the Armenians decided to secretly evacuate the fortress. However, the attempt was discovered and all who had left were killed. On July 12 those still inside the fortress surrendered. A massacre then followed in which all Armenian men were killed. Women and children survivors were held prisoner in the town before being deported like those of other towns.[18] Official Turkish records claim that during the revolt the Armenian rebels killed 403 civilian Turkish villagers.[19]

The Republic of Turkey

editWhen the republic was founded in 1923 the 10th Army was garrisoned here, bringing a boost to the local economy. Atatürk visited in 1924, on his way from seeing earthquake damage in Erzurum.

Geography

editŞebinkarahisar is a quiet town, 40 km from the provincial city of Giresun, standing on the north side of the valley of the river Avutmuş in the Giresun Mountains.

The town is hard to reach, the road along the riverbank is windy and narrow, and services are hard to provide.

The Şebin walnut is a particular variety of walnut grown on the valley sides.[20][dead link] Other local delicacies include a helva made from hazelnuts, a kind of cheese pudding called hoşmerim, small bread loaves called gilik, the corn and chick pea soup toyga çorbası, dolma made from the leaves of curled dock called evelik, stewed nettles and most of all the mulberry syrup, pekmez.

Climate

editŞebinkarahisar has a dry-summer continental climate (Köppen: Dsb),[21] with warm, dry summers, and cold winters.

| Climate data for Şebinkarahisar (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49.49 (1.95) |

45.72 (1.80) |

57.68 (2.27) |

79.65 (3.14) |

74.95 (2.95) |

39.18 (1.54) |

12.2 (0.48) |

8.82 (0.35) |

25.72 (1.01) |

55.02 (2.17) |

56.32 (2.22) |

50.87 (2.00) |

555.62 (21.87) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.7 | 8.1 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 86.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70.3 | 67.5 | 62.7 | 58.1 | 60.0 | 58.5 | 53.4 | 52.8 | 53.7 | 61.3 | 65.1 | 70.3 | 61.1 |

| Source: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

Places of interest

edit- Şebinkarahisar castle

- Atatürk House

- Kümbet Yaylası - A camping place

- Behramşah Cami - mosque built by the Seljuk Turks, in the neighbourhood of Avutmuş.

- Taşhanlar - Ottoman-period stone caravanserai, at the entrance to the castle

- Fatih Cami - Ottoman mosque next to the castle

- Virgin Mary Monastery - A Christian Monastery

- Surp Asdvadzadzin, an Armenian church built in 1274. Although destroyed by an accidental fire in the late 1800s, it was rebuilt. The new church could house 3,000 attendees.[8]

Notable people

edit- Katakalon Kekaumenos, prominent Byzantine general of the mid-11th century

- İdil Biret (born 1941), pianist. Her mother is from a Şebinkarahisar family

- Rahşan Ecevit (1923–2020), political leader and wife of former Prime Minister of Turkey Bülent Ecevit

- Ara Güler (1928–2018), Armenian photographer, born to a Şebinkarahisar family,

- Aziz Nesin (1915–1995), writer, was born to a Şebinkarahisar family and at one stage campaigned for Şebinkarahisar to be made again into a province in its own right

- Aram Haigaz (1900–1986), Armenian writer

- Andranik Ozanian (1865–1927), an Armenian general, national hero and politician

- Harutiun Shahrigian (1860–1915), Armenian politician, soldier, lawyer, and author

- Toros Toramanian (1864–1934), an Armenian architect

- Mehmet Emin Yurdakul (1869–1944), writer, former member of parliament for Şebinkarahisar

- Erdal Eren (1961–1980), communist activist

- Ashot Zorian (1905–1970), Armenian Egyptian painter; lived in Şebinkarahisar in the 1910s[23][24]

References

edit- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Procopius De Aedificiis 3.4.6-7

- ^ Bryer, Anthony; Winfield, David (1985). Byzantine Monuments and Topography of the Pontos. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. p. 146. ISBN 0-88402-122-X.

- ^ Cahen, Claude (2014). Holt, P.M. (ed.). The Formation of Turkey: The Seljukid Sultanate of Rum: Eleventh to Fourteenth Century. Routledge. p. Second page of Chapter 5. ISBN 9781317876250. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Bryer and Winfield, p. 146

- ^ W. M. Ramsay, The Historical Geography of Asia Minor, Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-108-01453-3, p. 57.

- ^ a b "From the Cultural Heritage Map: Şebinkarahisar Surp Asdvadzadzin". Hrant Dink Foundation.

- ^ Presenting Nikopolis (Garasari) region in greek

- ^ a b Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. p. 1138. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ Bryer and Winfield, p. 148

- ^ Winfield, David (1977). "The Northern Routes across Anatolia". Anatolian Studies. 27: 151–166. doi:10.2307/3642660.

- ^ Babinger, Franz (1978). Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time. Bollingen Series XCVI. ed. by William C. Hickman, trans. by Ralph Manheim. Princeton University Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-691-09900-6.

- ^ Robert W. Edwards, “The Fortress of Şebinkarahisar (Koloneia),” Corso di Cultura sull' Arte Ravennate e Bizantina 32 (1985), pp. 23-64.

- ^ Kemal Karpat (1985), Ottoman Population, 1830-1914, Demographic and Social Characteristics, The University of Wisconsin Press, p. 136-137

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian, "The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics" Published 1992 Palgrave Macmillan, p. 289, ISBN 0-312-04847-5

- ^ Edmund Herzig, Marina Kurkichayan, "The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity", Published 2005 Routledge, pg. 93, ISBN 0-7007-0639-9

- ^ Payaslian, Simon (2004). "The Armenian Resistance at Shabin-Karahisar in 1915". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Armenian Sebastia/Sivas and Lesser Armenia. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. pp. 399–426.

- ^ Öztürk, Özhan (2011). Pontus: Antik Çağ’dan Günümüze Karadeniz’in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi (Pontus: The Ethnic and Political History of the Black Sea Region from Antiquity to Today) (in Turkish). Ankara: Genesis Yayınları. pp. 543–544. ISBN 978-605-54-1017-9. book description Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Þebin Cevizi.Net - Anasayfa

- ^ "Table 1 Overview of the Köppen-Geiger climate classes including the defining criteria". Nature: Scientific Data.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Şebinkarahisar". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ Yan, Nair (2016-10-27). "Ashod Zorian Paintings Donated to the Armenian National Gallery". The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Ashod Zorian (1905–1970)". Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) Egypt. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

External links

edit- Photos of Şebinkarahisar(in Turkish)

- Carefully documented photographic survey and plan of the fortress at Şebinkarahisar

- The Municipality (in Turkish)

- Local İnformation (in Turkish)

- More Photos (in Turkish)

- Local News (in Turkish)