Kashmar (Persian: کاشمر; /kɑːʃˈmær/)[a] is a city in the Central District of Kashmar County, Razavi Khorasan province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district.[4] Kashmar is near the river Shesh Taraz in the western part of the province, and south of the province's capital Mashhad, in Iran, from east to Bardaskan, west to Torbat-e Heydarieh, north to Nishapur, south to Gonabad. Until two centuries ago, this city was named Torshiz (ترشیز).

Kashmar

Persian: کاشمر | |

|---|---|

City | |

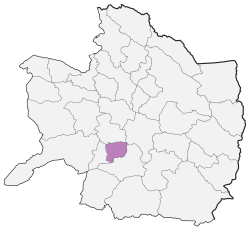

Location of Kashmar County in Razavi Khorasan province | |

| Coordinates: 35°14′41″N 58°27′39″E / 35.24472°N 58.46083°E[1] | |

| Country | Iran |

| Province | Razavi Khorasan |

| County | Kashmar |

| District | Central |

| Elevation | 1,063 m (3,488 ft) |

| Population (2016 Census)[2] | |

| • Urban | 102,282 |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| Area code | (+98) 051 552 |

| Kashmar at GEOnet Names Server | |

Demographics

editPopulation

editAt the time of the 2006 National Census, the city's population was 81,527 in 21,947 households.[5] The following census in 2011 counted 90,200 people in 26,445 households.[6] The 2016 census measured the population of the city as 102,282 people in 31,775 households.[2]

Historical legends

editKashmar is a city with ancient history and many legendary stories Among the historical legends are about the Cypress of Kashmar.[7]

Cypress of Kashmar

editThe Cypress of Kashmar is a mythical cypress tree of legendary beauty and gargantuan dimensions. It is said to have sprung from a branch brought by Zoroaster from Paradise and to have stood in today's Kashmar in northeastern Iran and to have been planted by Zoroaster in honor of the conversion of King Vishtaspa to Zoroastrianism. According to the Iranian physicist and historian Zakariya al-Qazwini King Vishtaspa had been a patron of Zoroaster who planted the tree himself. In his ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt, he further describes how the Al-Mutawakkil in 247 AH (861 AD) caused the mighty cypress to be felled, and then transported it across Iran, to be used for beams in his new palace at Samarra. Before, he wanted the tree to be reconstructed before his eyes. This was done in spite of protests by the Iranians, who offered a very high sum of money to save the tree. Al-Mutawakkil never saw the cypress, because he was murdered by a Turkish soldier (possibly in the employ of his son) on the night when it arrived on the banks of the Tigris.[8][9]

Fire Temple of Kashmar

editKashmar Fire Temple was the first Zoroastrian fire temple built by Vishtaspa at the request of Zoroaster in Kashmar. In a part of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, the story of finding Zarathustra and accepting Vishtaspa's religion is regulated that after accepting Zoroastrian religion, Vishtaspa sends priests all over the universe And Azar enters the fire temples (domes) and the first of them is Adur Burzen-Mihr who founded in Kashmar and planted a cypress tree in front of the fire temple and made it a symbol of accepting the Zoroastrian religion. And he sent priests all over the world, and commanded all the famous men and women to come to that place of worship.[10]

Religion

editThe city is fourth pilgrimage city in Iran and it is the second most pilgrimage city after Mashhad in Razavi Khorasan Province.[11]

Education

editAt present, Kashmar has five higher education centers, including Payame Noor University of Kashmar, Islamic Azad University of Kashmar,[12] Jihad University of Kashmar, Kashmar Higher Education Center and the School of Nursing. According to the statistics of the above institute, 3,794,420 students are studying in the country's universities, of which about 3,500 are Kashmir students.[13]

Souvenirs

editThe city is a major producer of raisins and has about 40 types of grapes. It is also internationally recognized for exporting saffron and handmade Persian rugs. The main souvenirs of this city are the Kashmar carpet, raisins, grapes, saffron, dried fruits, and the confectionary sohan.[14]

Kashmar carpet

editKashmar carpet is a regional Persian carpet named after its origin, the city of Kashmar, that is produced throughout the Kashmar County. The carpets are handmade and are often available with landscape and hunting designs.[15][16][17] The history of carpet weaving in Kashmar dates back to 150 years and the contemporary art of carpet weaving dates back to 1920. However, between 1260 and 1280, mass production of carpets was recorded by historians. The first master weaver in the Kashmar region was Mohammad Kermani, who, despite his last name, was not from Kerman, but people say he was born in a village called Forutqeh near Kashmar. According to historians, the master weaver brought the knowledge of carpet weaving from Kerman province, and his first work was probably commissioned by Saeed Hossein Sajjadi, a native and resident of Forutqeh and a famous carpet manufacturer.[18]

Alcoholic beverages

editDespite the prohibition of alcohol in Iran, Kashmar is reported to have 3300 hectares of vineyards.[19] 50% of the raisins produced in the city are exported to Europe.[20] In Germany, a company produces its beverages with the brand "Kashmar", which is especially favoured among the Iranian diaspora in Germany.[19] The unregulated and illegal production of alcohol within the city caused two deaths in 2018 from intoxication.[21] in the same year, a manufactury with 300 liters alcohol was found and destroyed.[22]

Historical sites, ancient artifacts and tourism

editTomb of Hassan Modarres

editThe Tomb of Sayyid Hassan Modarres is the burial site of Sayyid Hassan Modares, former Prime Minister of Iran. It was built in 1937 in Kashmar, Iran, as opposed to using the former tomb of Kashmar in the vast gardens of Kashmar. The tomb building consists of a central dome, four dock and a dome made of turquoise, in the style of Islamic architecture and the Safavid dynasty. Seyed Hassan Modares lived during the Pahlavi dynasty and was from the Sadat of Tabatabai. He was a political constitutionalist.[23][24][25]

Hassan Modarres Museum

editThe Hassan Modarres Museum is a Museum belongs to the 21st century and is located in Kashmar, Razavi Khorasan Province in Iran.[26][27]

Imamzadeh Seyed Morteza

editImamzadeh Seyed Morteza is related to the Qajar dynasty and is located in Razavi Khorasan Province, Kashmar. Massive trees, waterfalls and swimming pools add to the attractions of this place, and on the other hand, a good number of living rooms provide a good base for traveling to this place, as well as the many shops and dining halls.[28][29]

Imamzadeh Hamzeh

editImamzadeh Hamzah, Kashmar the oldest mosque in Kashmar, includes the tomb of Hamza al-Hamza ibn Musa al-Kadhim, the garden and the public cemetery, and is as an Imamzadeh.[30][31]

Jameh Mosque of Kashmar

editJameh Mosque of Kashmar, the place where Jumu'ah is performed, was built in Kashmar in 1791 by Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. This Mosque is opposite the Amin al-tojar Caravansarai.[32][33]

Haji Jalal Mosque

editHaji Jalal Mosque is a Qajar dynasty period mosque in Kashmar, Razavi Khorasan Province.[34]

Kohneh Castle, Zendeh Jan

editKohneh Castle is a Castle related to the 1st millennium and is located in the Kashmar County, Zendeh Jan village.[35]

Atashgah Manmade-Cave

editThe Atashgah Manmade-Cave or Atashgah Cave is located 20 km (12 mi) northwest of Kashmar city, Iran and the cave has two entrance passages.[36]

Atashgah Castle

editAtashgah Castle is a castle in the city of Kashmar, and is one of the attractions of Kashmar. This castle was built by the Sasanian government and it was famous in ancient times.[37][38]

Rig Castle

editRig castle is a Castle related to the Seljuq dynasty and is located in the Kashmar County, Quzhd village.[39][40]

Amin al-tojar Caravansarai

editAmin al-tojar Caravansarai is a caravanserai related to the Qajar dynasty and is located in Kashmar. This Caravansarai is opposite the Jameh Mosque of Kashmar.[41][42]

Haj Soltan Religious School

editThis school is one of the buildings of the Qajar era, which has a central courtyard and is surrounded on four sides by two-story rooms and two north and south porches.[43][44]

Talaabad Watermill

editTalaabad Watermill is a Watermill related to the late Safavid period and is located in Kashmar County, Central District, Quzhd village.[45][46]

Yakhchāl of Kashmar

editThe Yakhchāl of Kashmar is a historical Yakhchāl belongs to the Qajar dynasty and is located in Kashmar County, Razavi Khorasan Province.[47]

Arg of Kashmar

editArg of Kashmar Or Arg of Hosen is a historical Citadel located in Kashmar County in Razavi Khorasan Province, The lifespan of this building goes back to Qajar dynasty.[48]

Imamzadeh Mohammad

editImamzadeh Mohammad is a Imamzadeh belongs to the History of modern and is located in Kashmar County, Razavi Khorasan Province in Iran.[49][50]

Grave of Pir Quzhd

editGrave of Pir Quzhd is a historical Grave related to the Before the 11th century AH and is located in Quzhd, Razavi Khorasan Province.[51][52]

Qanats of Quzhd

editThe Qanats of Quzhd is a historical Qanat is located in Quzhd in Kashmar County.[53][54]

Seyed Morteza Forest Park

editThe Seyed Morteza Forest Park is a Forest Park is located in Kashmar, Razavi Khorasan Province in Iran.[55][56]

Ultralight Airport Kashmar

editUltralight Airport Kashmar is an airport in the city of Kashmar in Iran, which is located on a 17-hectare land in the southwest of Razavi Khorasan province, about 240 kilometers from the city of Mashhad; And with one runway, it has the capacity to accept all light and ultralight aircraft.[57]

Notable people

editManouchehr Eghbal

editManuchehr Eqbal (Persian: منوچهر اقبال; 13 October 1909 – 25 November 1977) was an Iranian royalist politician. He held office as the Prime Minister of Iran from 1957 to 1960. He served as the minister of health in Ahmad Ghavam's cabinet, minister of culture in Abdolhosein Hazhir's cabinet, minister of transportation in RajabAli Mansur's cabinet, and interior minister in Mohammad Sa'ed's cabinet. He also served as the governor of East Azarbaijan province.[58] In 1957, he became prime minister, replacing Hussein Ala.[58][59] Eghbal continued as prime minister until fall 1960 and was replaced by Sharif Emami.[60] Until his death, he served as a top executive in Iran's National Oil Company. He was also one of the close aides to the Shah.[61]

Fateme Ekhtesari

editFateme Ekhtesari, also Fatemeh Ekhtesari, (born 1986) is an Iranian poet.[62][63] Ekhtesari lived in Karaj and she writes in Persian.[64] In 2013, she appeared at the poetry festival in Gothenburg (Göteborgs poesifestival). After she arrived back in Iran she was imprisoned and later released on bail. Her verdict came in 2015 when she was sentenced to 99 lashes and 11.5 years imprisonment for crimes against the Iranian government, for immoral behaviour and blasphemy.[65]

Alireza Faghani

editAlireza Faghani (Persian: عليرضا فغانى, born 21 March 1978) is an Iranian international football referee who has been officiating in the Persian Gulf Pro League for several seasons and has been on the FIFA list since 2008. Faghani has refereed important matches such as the 2014 AFC Champions League Final, the 2015 AFC Asian Cup Final, the 2015 FIFA Club World Cup Final, the 2016 Olympic football final match. He has refereed matches in the 2017 Liga 1, 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup, 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia and the 2019 AFC Asian Cup. Alireza migrated to Australia in September 2019.

Fereydoun Jeyrani

editFereydoun Jeyrani (Persian: فریدون جیرانی; born in 1951, Bardaskan) is an Iranian film director, screenwriter, and Television presenter. He was the director, producer and host of haft (Seven) (an Iranian television series about Iranian Cinema) until 2012. Along with his unconventional performance in Haft, he is best known for directing Red, The Season Salad, Water and Fire, Pink and I am a Mother.[66][67] Jeyrani TV Host Haft First series.

Mohammad Khazaee

editMohammad Khazaee (Persian: محمد خزاعی, born 12 April 1953 in Kashmar, Iran)[68] is the former Ambassador of Iran to the United Nations. He presented his credentials to the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in July 2007.[68] He was elected as Vice President of the United Nations General Assembly on 14 September 2011.

Ali Rahmani

editAli Rahmani (علی رحمانی) was born in Kashmar (25 May 1967). He was the first managing director of Tehran Stock Exchange.[69][70] He is an associate professor at Alzahra University.

Iran Teymourtash

editIran Teymourtāsh (Persian: ایران تیمورتاش; 1914–1991), the eldest daughter of Abdolhossein Teymourtāsh, is considered a pioneer among women activists in 20th-century Iran. Her father's position as the second most powerful political personality in Iran, from 1925 to 1932, afforded Iran Teymourtāsh the opportunity to play a prominent role in that country's women's affairs early in life.[71][72][73]

Military operations

editIran–U.S. RQ-170 incident

editOn 5 December 2011, an American Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was captured by Iranian forces near the city of Kashmar in northeastern Iran. The Iranian government announced that the UAV was brought down by its cyberwarfare unit which commandeered the aircraft and safely landed it, after initial reports from Western news sources disputedly claimed that it had been "shot down".[74] The United States government initially denied the claims but later President Obama acknowledged that the downed aircraft was a US drone.[75][76] Iran filed a complaint to the UN over the airspace violation. Obama asked Iran to return the drone. Iran is said to have produced drones based on the captured RQ-170.

Ban of Americans

editIn 2018, a pair of American citizens were issued hunting permits by the city of Kashmar. This was seen as irregular, and a commission was formed to protect the interests of the city against foreign influence. All involved departments were investigated severely and American citizens were banned from entering the city.[77]

Kashmar Great earthquake

editThe Kashmar earthquake occurred on 25 September 1903, at 1:20 am UTC time in Iran. Its magnitude is 6.5 on the Richter scale. The U.S. Geological Survey[78] also estimated the quake at 35°12′N 58°12′E / 35.2°N 58.2°E E and its magnitude was 6.5 on the Richter scale..

The death toll from the earthquake was about 200.

Geographical location

editKashmar County with two central district and Farah Dasht, and to the center of Kashmar city has occupied an area of about 3390 square kilometers of Khorasan Razavi Province With the County of Kuhsorkh. This city is adjacent to Khalilabad from the west, to Nishapur and Bardaskan from the north and northwest, to Torbat-e Heydarieh from the east and northeast, and to the Feyzabad from the south and southwest. Kashmar city has two mountainous areas of the Rivash in the north and Fagan Bajestan heights in the south and desert and arid regions in the west and south and fertile plains in the suburbs and its towns. In terms of climate, it can be said that Kashmar has all three types of climate because the northern parts of the city are mountainous and cold, the central regions are temperate and the southern regions are arid and semi-arid due to its proximity to the Lut desert.[79][80]

Climate

editKöppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies its climate as cold desert (BWk) with short, cool winters and long, hot summers.[81]

| Climate data for Kashmar (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

26.4 (79.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35.4 (95.7) |

38.6 (101.5) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.6 (108.7) |

42.6 (108.7) |

38.4 (101.1) |

35.2 (95.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

35.5 (95.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

29.2 (84.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.8 (3.6) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−15.8 (3.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.1 (1.22) |

33.7 (1.33) |

45.4 (1.79) |

28.5 (1.12) |

12.7 (0.50) |

1.8 (0.07) |

0.7 (0.03) |

0.2 (0.01) |

1.0 (0.04) |

4.4 (0.17) |

12.9 (0.51) |

22.3 (0.88) |

194.7 (7.67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 29.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61.0 | 55.0 | 48.0 | 40.0 | 30.0 | 22.0 | 21.0 | 21.0 | 23.0 | 32.0 | 46.0 | 57.0 | 38.0 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 184.0 | 186.0 | 212.0 | 251.0 | 308.0 | 348.0 | 370.0 | 361.0 | 317.0 | 281.0 | 215.0 | 188.0 | 3,221 |

| Source: NOAA[82] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

edit-

Kashmar Enghelab sport complex

-

Tree in Kudak park

-

Traffic police booth

-

Shohada' Square

-

Old wooden door Symbol Kashmar

-

Grave of Pir Quzhd

-

Yakhchāl of Eshaqabad

-

Yakhchāl of Talabad

-

Rig Castle

-

Amin al-tojar Caravansarai

-

Jameh Mosque of Kashmar

-

Kashmar in 2021

-

Kashmar in 2021

-

Kashmar in 2021

-

Imamzadeh Mohammad in 2021

-

Haji Jalal Mosque in 2021

Media related to Kashmar at Wikimedia Commons

Kashmar travel guide from Wikivoyage

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ OpenStreetMap contributors (1 November 2024). "Kashmar, Kashmar County" (Map). OpenStreetMap (in Persian). Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ a b Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1395 (2016): Razavi Khorasan Province. amar.org.ir (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Kashmar can be found at GEOnet Names Server, at this link, by opening the Advanced Search box, entering "-3069992" in the "Unique Feature Id" form, and clicking on "Search Database".

- ^ Habibi, Hassan (c. 2015) [Approved 21 June 1369]. Approval of the organization and chain of citizenship of the elements and units of the divisions of Khorasan province, centered in Mashhad. rc.majlis.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Defense Political Commission of the Government Council. Proposal 3223.1.5.53; Approval Letter 3808-907; Notification 84902/T125K. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2024 – via Islamic Parliament Research Center.

- ^ Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006): Razavi Khorasan Province. amar.org.ir (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1390 (2011): Razavi Khorasan Province. irandataportal.syr.edu (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2022 – via Iran Data Portal, Syracuse University.

- ^ "كاشمر شهر سروهاي افسانه اي". Mehr News Agency. 19 March 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "The Destruction of Sacred Trees". www.goldenassay.com. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "The Cypress of Kashmar and Zoroaster". www.zoroastrian.org.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "تاریخچه و نقشه جامع شهر کاشمر در ویکی آنا". ana.press. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "دومین شهر زیارتی خراسان رضوی". khorasan.iqna.ir. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Islamic Azad University Kashmar | Admission | Tuition | University". www.unipage.net. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "گهواره های دانش در کاشمر، مهد پرورش نخبگان". Young Journalists Club. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "اداره میراث فرهنگی شهرستان کاشمر – سوغات کاشمر". kashmar.razavichto.ir. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Ford, P.R.J. (1989). The oriental carpet: a history and guide to traditional motifs, patterns, and symbols. Portland House. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-517-67224-2. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

The town of Kashmar in Khorassan province, between Meshed and Birjand, weaves carpets in a variety of styles and in a stitch which may also be described as intermediate between Meshed and Birjand. The design shown ...

- ^ Bennett, I.; Aschenbrenner, E.; Parsons, R.D. (1981). Oriental Rugs: Persian. Oriental Textile Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-907462-12-5. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

Kashmar lies at the edge of the great salt desert about 150 km (100 miles) south-west of Meshed. Under its earlier name of Turshiz its carpets had an indifferent reputation. The change of name occurred under the reign of ...

- ^ Carpet Museum of Iran (2001). The indigenous elegance of Persian carpet: a collection from the Carpet Museum of Iran. Andishe Zand Pub. Co. p. 57. ISBN 9789649063034. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Review of the Carpet Industry in Kashmar". www.jozan.net. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ a b "تولید عرق کاشمر با نشان شیر درآلمان". VOA-PNN (in Persian). Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "صادرات 50 درصد کشمش کاشمر به کشورهای اروپایی". ایسنا (in Persian). 27 October 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "يك نفر ديگر از مصرف كنندگان مشروبات الكلي در كاشمر جان باخت". ایرنا (in Persian). Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "300 ليتر مشروبات الكلي در كاشمر كشف شد". ایرنا (in Persian). Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Seyed Hassan Modares Tomb". en.shahrmajazi.com. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Tomb of Hassan Modares on site seeiran

- ^ "Seyed Hassan Modares Tomb". www.itto.org. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "موزه شهید مدرس؛ نمایشگر بخشی از هویت تاریخی کاشمر". khorasan.iqna.ir. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "200 اثر در موزه شهيد مدرس نگهداري مي شود". Islamic Republic News Agency. 24 November 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "امامزاده سید مرتضی(ع)؛ نگین گردشگری مسافران نوروزی". International Quran News Agency. khorasan.iqna.ir. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "امامزاده سید مرتضی فرصتی برای گردشگری مذهبی در شهرستان کاشمر". www.dana.ir. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Imamzadeh Hamzeh". Imamzadeh Hamzeh; Shelter of travelers to the sun. iqna. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "امام زاده سید حمزه کاشمر ،نگین فرهنگی منطقه". www.dana.ir. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Kashmar information database". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "مسجد جامع کاشمر؛ میراثی ماندگار با قدمتی بیش از دو قرن + عکس". khorasan.iqna.ir. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "معرفی مسجد حاجي جلال شهرستان کاشمر". salamabadi.ir. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "قلعه کهنه زنده جان". seeiran.ir. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "غارهایی در دل طبیعت خراسان رضوی+تصاویر". Tasnim News Agency. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Atashgah castle". www.itto.org. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Irania Encyclopedia (Persian)". Irania Encyclopedia.

- ^ "بقایای قلعه ریگ". www.kojaro.com. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "معرفی بقایای قلعه ریگ". salamabadi.ir. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "موقوفه امین التجار با بیش از یک قرن قدمت". www.qudsonline.ir. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "موقوفه "امین التجار"؛ نگین گردشگری در جنوب خراسانرضوی". Tasnim News Agency. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "مدرسه حاج سلطان میراثی که در سکوت متولیان تخریب می شود/ قديمي ترين حوزه علميه کاشمر در آستانه نابودی". Mehr News Agency. 23 July 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "مدرسه علمیه حاج سلطان العلماء". seeiran.ir. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "فهرست آثار ثبتی – اداره میراث فرهنگی شهرستان کاشمر". kashmar.razavichto.ir. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "آسیاب آبی طلاآباد کاشمر". aftab-hotel.com. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "یخدان فروتقه کاشمر مرمت-شد". Islamic Republic News Agency. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "خرابه های ارگ قدیم". seeiran.ir. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "بازسازی امامزاده سیدمحمد کاشمر نیازمند کمک خیران است". Tasnim News Agency. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "مقبره امامزاده سيد محمد كاشمر به عنوان ميقات الرضا (ع) شناخته شد". Islamic Republic News Agency. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "چهارشنبهي اهالي کاشمر... معرفي "مزار پير" در گزارش ايسنا". Iranian Students News Agency. 28 September 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "مزار پيران در آبادیهای كاشمر نياز به توجه دارد". iqna.ir. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "قناتهاي کاشمر، ميراث در خطر". Iranian Students News Agency. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ "بانک اطلاعاتي قنات هاي کشور". www.webcitation.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ "پارک جنگلی سید مرتضی". seeiran.ir. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "کاشمر، دیار سروهای سر به فلک کشیده". www.kashmari.ir. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "معاون ناجا از فرودگاه سبک کاشمر بازدید کرد". Islamic Republic News Agency. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Iran premier will quit". Schenectady Gazette. 2 April 1957. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Iran minister resigns post". Gettysburg Times. Tehran. 3 April 1957. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Iran teachers' protest Iranian premier from office". The Press Courier. 5 May 1961. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ "Centers of Power in Iran" (PDF). CIA. May 1972. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Poeter fängslade". Aftonbladet. 26 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Sveriges Radio (6 September 2013). "Ung persisk poesi gör motstånd". Sveriges Radio. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Kritiker, Medverkande, 2013, En motståndsrörelse på mitt skrivborg, page 185

- ^ "Iranska poeter ska ha släppts". SVT. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Shakhsiatnegar

- ^ Cinetmag

- ^ a b United Nation's press release

- ^ Theodoulou, Michael (7 October 2008). "US economic crisis gives cheer in Tehran". The National. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012.

- ^ "Tehran Stock Exchange names Ali Rahmani MD" (Press release). Tehran Stock Exchange. 2 January 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Agheli, Bagher, Teymourtash Dar Sahneye-h Siasate-h Iran ("Teimurtash in the Political Arena of Iran") (Javeed: Tehran, 1371).

- ^ Behnoud, Masoud, Een Se Zan, Ashraf Pahlavi, Mariam Firouz, va Iran Teymourtash

- ^ Cronin, Stephanie, The Making of Modern Iran: State and Society Under Reza Shah (Routledge: London, 2003) ISBN 0-415-30284-6.

- ^ Peterson, Scott; Faramarzi, Payam (2011). "Exclusive: Iran hijacked US drone, says Iranian engineer". csmonitor.com. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Mungin, Lateef (22 October 2013). "Iran claims released footage is from downed U.S. drone". CNN.

- ^ "Obama says U.S. has asked Iran to return drone aircraft". CNN. CNN Wire Staff. 22 October 2013.

- ^ "جلوگیری از ورود آمریکاییها به کاشمر". Iranian Students News Agency. 23 June 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ The Preliminary Determination of Epicenters (PDE) Bulletin

- ^ "اداره کل میراث فرهنگی گردشگری و صنایع دستی خراسان رضوی". kashmar.razavichto.ir. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "نگاهي به جاذبه هاي تاريخي و گردشگري كاشمر". Islamic Republic News Agency. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Climate: Kashmar – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Kashmar". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 1 January 2024.