The Jewel Tower is a 14th-century surviving element of the Palace of Westminster, in London, England. It was built between 1365 and 1366, under the direction of William of Sleaford and Henry de Yevele, to house the personal treasure of King Edward III. The original tower was a three-storey, crenellated stone building which occupied a secluded part of the palace and was protected by a moat linked to the River Thames. The ground floor featured elaborate sculpted vaulting, described by historian Jeremy Ashbee as "an architectural masterpiece". The tower continued to be used for storing the monarch's treasure and personal possessions until 1512, when a fire in the palace caused King Henry VIII to relocate his court to the nearby Palace of Whitehall.

| The Jewel Tower | |

|---|---|

| Part of Palace of Westminster | |

| Old Palace Yard, London, England | |

The Jewel Tower | |

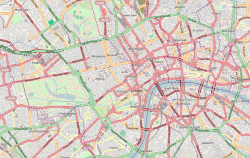

| Coordinates | 51°29′54″N 0°07′35″W / 51.498417°N 0.126472°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Intact |

| Site history | |

| Built by | Henry Yevele |

| Materials | Kentish Ragstone |

| Events | Westminster Palace fires of 1512 and 1834 |

At the end of the 16th century the House of Lords began to use the tower to store its parliamentary records, building a house alongside it for the use of the parliamentary clerk, and extensive improvements followed in 1621. The tower continued as the Lords' records office through the 18th century and several renovations were carried out to improve its fire-proofing and comfort, creating the present appearance of the tower. It was one of only four buildings to survive the burning of Parliament in 1834, after which the records were moved to the Victoria Tower, built for the purpose of storing archives, and part of the new neo-Gothic Palace of Westminster.

In 1869 the Jewel Tower was taken over by the newly formed Standard Weights and Measures Department, which used it for storing and testing official weights and measures. The tower became less and less suitable for this work as passing vehicular traffic increased, and by 1938 the department had given up on it in favor of other facilities. In 1948 the building was placed into the care of the Ministry of Works, which repaired the damage inflicted to the tower during the Second World War and restored the building extensively, clearing the surrounding area and opening the tower to tourists. Today the Jewel Tower is managed by English Heritage and receives about 30,000 visitors annually.

History

edit14th–16th centuries

editPurpose

editThe Jewel Tower was built within the Palace of Westminster between 1365 and 1366, on the instructions of King Edward III, to hold his personal treasure.[1] Edward had broadly three types of treasure: his ceremonial regalia, which was usually kept at the Tower of London or held by the Abbot of Westminster; the jewellery and plate belonging to the Crown, which was kept by the Royal Treasurer at Westminster Abbey; and his personal collection of jewels and plate.[2] English monarchs during this period used their personal jewels and plate as a substitute for cash, drawing on them to fund their military campaigns, or giving them as symbolic political gifts.[3] Edward accumulated what historian Jenny Stratford has described as a "vast store of jewels and plate", and his collection of personal treasure was at its greatest during the 1360s.[4]

Edward had managed this last category of personal treasure through an organisation called the Privy Wardrobe.[5] The Keeper of the Privy Wardrobe was responsible for guarding and recording the king's belongings, and dispatching particular items around the kingdom, potentially giving them as gifts to the monarch's family and friends.[6] The Privy Wardrobe was initially based in the Tower of London in Edward's reign and became focused on handling the supplies for his campaigns in France.[5] This probably encouraged the King to decide to build a new tower in Westminster to host a separate branch of the Privy Wardrobe specifically to manage his personal jewels and plate.[5] In practice, this branch also managed the clothes, vestments and similar goods belonging to the royal household – effectively, the non-military parts of the King's property.[7]

Construction

editWilliam of Sleaford was put in charge of the tower project as a whole; he was the clerk and surveyor of the king's works within the Palace of Westminster and the Tower of London, and became the Keeper of the Westminster Privy Wardrobe.[5] The Jewel Tower was designed and built by Henry de Yevele, a prominent royal architect, supported by a team of masons he commissioned for both this project and a neighbouring piece of work to build a new clock tower nearby.[8] Hugh Herland was taken on as the chief carpenter for both projects.[8] The payments for the project were recorded on an 8-foot-6-inch (2.59 m) long parchment roll, which is now held in the Public Record Office.[1]

Stone was brought in for the two towers: 98 boat-loads of rough stone and 13,782 feet (4,201 m) of dressed stone from Maidstone; 469 cart-loads from Reigate; 26 long tons (26 t) from Devon and 16 long tons (16 t) from Normandy.[9] Timber was brought from Surrey, red floor tiles from Flanders and 97 square feet (9.0 m2) of glass purchased for the Jewel Tower alone.[10] A contractor was employed to fix iron grilles to the windows, and 18 locks were purchased to secure the various doors.[11] A main workforce of 19 stonemasons, up to 10 carpenters and other specialised tradesmen worked on the site, and in July 1366, a team of 23 labourers dug out the new moat over the course of a month.[12]

The tower was constructed in the secluded south-west corner of the Palace of Westminster, overlooking the king's garden in the Privy Palace, the most private part of Westminster.[13] The tower was positioned so as not to encroach on the existing palace, but this meant it was built on top of land owned by the neighbouring Westminster Abbey.[1] It took six years for the abbey to convince the king to agree to compensate for them for this annexation.[1] William Usshborne, one of Edward's officials, was blamed for this and, when he later choked to death while eating a fish from a pond in the palace, the monks argued that this was divine justice for his role in the affair.[14][nb 1]

The tower was linked to the external walls of the palace, and further secured by its moat, which was connected to the River Thames by a 45-metre (148 ft) channel.[16] The top of its walls were crenelated, and in order to prevent potential intruders there were no windows on the outside of the tower at the ground floor level.[17] The keeper would have worked from the first floor, and Edward's treasure itself was kept on the second floor, in locked chests.[18]

Later medieval use

editThe Jewel Tower continued to be used by Edward's successors for storing treasure and personal possessions, until 1512, when a fire in Westminster Palace forced the royal court to relocate to Whitehall, along with the jewels and plate from the tower.[19] The king, Henry VIII, did not return to Westminster and instead built a new palace at Whitehall, but he continued to use the tower, then called the "Tholde Juelhous" ("the old Jewel House") for storing his wider household effects, including expensive cloths, linens, royal chess sets and walking sticks, but these appear to have been removed from the tower after his death.[20]

The Jewel Tower diminished in importance; probably during the 16th century, the palace walls on either side of the building were demolished, and part of the moat was filled in during 1551.[21] By the 1590s, the tower had begun to be used both for the storage of the Lords' records and as a house for the parliamentary clerk.[22] In 1600, a three-storey timber extension was built on the side of the tower for the clerk's use, as part of a wider renovation of the tower at a cost of £166, and the complex began to be termed the Parliament Office rather than the Jewel Tower.[23][nb 2][nb 3] The ground floor of the tower may have begun to be used as a kitchen and scullery for the new house at around this time.[26]

17th–18th centuries

editIn 1621, a subcommittee of the House of Lords concluded that the Lords' record keeping should be improved, and the tower was renovated to improve its storage facilities.[27] The first floor of the tower, used to store the documents, was renovated with brick vaulting, providing better fire protection than the original wooden ceiling, by Thomas Hicks at a cost of £6.[28] The chamber was further protected by a new iron door.[29]

The parliamentary clerk continued to live alongside the tower, except during the interregnum of 1649 and 1660, when the House of Lords was temporarily abolished.[30] The sewer feeding into the moat was blocked up around the middle of the century, and the moat, which previously seems to have been kept clean, was allowed to gradually fill up with debris, despite complaints from the House of Lords that this put the Jewel Tower at greater risk of fire and thieves.[31]

By 1716, the tower was reported to Parliament as being in a "ruinous condition", and an enquiry concluded that repairs and restoration should go ahead at a cost of £870.[32][nb 4] The work commenced under Nicholas Hawksmoor, the Surveyor General, but staff turnover in the Office of Works and accusations of corruption slowed the work.[33] Cut-backs were made, in particular to the plans to strengthen the roof of the tower with fire-resilient brick vaults; despite this, the costs totalled £1,118 by the end of the project in 1719.[33] The outside of the tower was reworked to form its modern appearance, with plainer, larger windows and a simpler parapet, and a new chimney to keep members of the House of Lords warm while they were reading the records.[33] Specialised wooden cupboards and shelves were installed on the first floor to hold the documents.[34] Further work was carried out in 1726 to improve the security and safety of the tower, particularly from the threat of fire, at a cost of £508.[35]

At some point in the 18th century, possibly in 1753, the upper and lower halves of the tower were divided into two separate areas.[36] The spiral staircase from the ground floor kitchen to the upper floors, holding the records, was removed, and a window on the first floor was turned into a doorway so that the upper floors could be accessed from the neighbouring house.[26] A fire-resistant stone vaulted ceiling was installed in on the first floor, possibly also in 1753 at a cost of £350.[26]

An investigation by the Board of Works in 1751 concluded that the parliamentary clerk's house was in a poor condition and unsuitable for habitation.[37] In particular, it lacked a kitchen and scullery, and the cooking was still being carried out in the ground floor rooms of the Jewel Tower.[37] Two three-storey brick houses – later titled 6–7 Old Palace Yard – were built in its place between 1754 and 1755, possibly by the architect Kenton Couse, at a cost of £2,432.[38] The Jewel Tower was accessed from the Old Palace Yard through a central passageway that ran between the houses, and a range of subsidiary buildings were built behind the houses, joining them and the tower, while the tower continued to be used for preparing food.[38]

19th–21st centuries

edit1801–1945

editBy the 19th century, the tower was obscured by the surrounding buildings, and was accessed through the brick-built office in front of it, according to the antiquarian and engraver John Smith.[39] The tower began to become too small for storing all the House of Lords' records, and from 1827 onwards only the acts, journals and minute-books were kept in the tower.[40]

A fire swept through Westminster in 1834, destroying most of the old palace, but the Jewel Tower, which was separated from the main fire and was positioned away from the prevailing wind, survived, along with its store of records from the House of Lords.[41][nb 5] Westminster was rebuilt, and in 1864 substantial changes were made at the tower: the Parliamentary records in the tower were moved to a fire-proof storage facility at the new Victoria Tower; 6–7 Old Palace Yard ceased to be used by the clerk as a house, and the kitchen in the ground floor of the tower was closed.[43] Around this time, the tower began to be called the Jewel Tower once again, partially in the incorrect belief that it had held the Crown Jewels during the medieval period.[44]

In 1866, the Standards of Weights, Measures, and Coinage Act was passed by Parliament, creating a department of the Board of Trade called the Standard Weights and Measures Department.[45] This department was responsible for maintaining the weights and measures used in the country – in particular, the primary and secondary standards, the physical "master" weights and lengths that other measuring devices could be compared against.[46]

The house alongside the Jewel Tower was taken over by the new department in 1869, and the standards and testing equipment were installed in the tower itself, which was felt to be particularly suitable for making scientific measurements, because of its thick walls.[47] The roof, which was in poor condition, was repaired.[48] The ground floor was used as a weighing room and for storing glass fluid measures, the first floor held the standards of length, and the second floor was used as a museum to display old historical equipment.[48]

During the coming decades, however, the suitability of the tower for the work of the department came into question.[48] The condition of the roof remained problematic, and steel girders had to be added to support the main timbers.[49] Increasing traffic levels around the tower led to subsidence and high levels of vibration, effecting the operation of the delicate instruments, and worsened after the opening of Lambeth Bridge in 1932.[48] Some of the department's work was transferred to their Bushy House facility in Teddington in the 1920s, and in 1938 the department relinquished the tower altogether.[50]

In the Second World War, the tower was hit by an incendiary device dropped by German bombers in 1941.[51] The resulting fire caused significant damage to the roof, destroying much of the original fabric.[52]

Post-war and 21st century

editRestoration

editThe tower was placed into the guardianship of the Ministry of Works in 1948.[53] The ministry carried out extensive repairs, attempting to retain a mixture of the medieval and newer features in the building.[54] They removed the old medieval elm and oak foundations and replaced them with concrete supports, and installed a replacement roof in 1949, removing the first floor entrance and reinstalling the spiral staircase from the ground floor in 1953.[55] The inside of the tower was rendered to hide the traces of the various work.[54] The Jewel Tower was opened for tourists in 1956, and drew between 500 and 800 visitors each week.[56]

Between 1954 and 1962, most of the buildings that had been constructed around the tower over the years, including the parliamentary legal offices, a stable, a row of houses and the Prime Minister's chauffeur's house, were demolished, and a new garden, College Green, was laid out beside the tower, on top of an underground parking lot.[57] The medieval moat was re-excavated in 1956, and filled with water between 1963 and the 1990s, when its poor water quality led to its being drained and lined with gravel.[58]

Several archaeological investigations into the tower were carried out in the post-war period.[59] Investigations were carried out during the renovations throughout 1948 to 1956. Further work followed to the east of the tower between 1962 and 1964, uncovering the landing dock.[60] Another project was carried out in 1994 and 1995, uncovering part of the original garden of the tower and the 16th-century adjoining timber house, and an architectural survey between 2009 and 2011 determined that one of the wooden doors on the second floor was probably an original feature from 1365.[61]

Tourism

editIn the 21st century the Jewel Tower is managed by English Heritage as a tourist attraction, and protected under UK law as a scheduled monument[62] and a Grade I Listed Building.[63] [64] In 1987 the Jewel Tower and the surrounding site of Westminster Palace were declared a World Heritage Site, the UN noting that the tower formed one of the "precious vestiges of medieval times" in the area.[65]

Between 2007 and 2012 an average of 30,000 visitors came to the tower each year, with non-English speaking visitors making up a high proportion.[66] The architecture of the tower has made it a challenging site to operate as a tourist attraction; the fluctuating heat and humidity, and capacity constraints, have prevented it being adapted to house more delicate historical artefacts or accommodate additional visitor numbers.[67]

Archaeologists have recovered over 400 objects associated with the tower, and various Delftware drinking jars and an Iron Age sword are displayed inside, along with a set of historiated capitals, described by the historian Jeremy Ashbee as "important and rare examples of English Romanesque sculpture", originating from the Westminster Hall of the 1090s, and a set of weights and measures, on loan from the Science Museum.[68]

Architecture

editThe Jewel Tower is a three-storey building of Kentish ragstone with a brick parapet, structurally largely unchanged since the 14th century.[69] The walls that once faced away from the palace are finely coursed, but the interior two walls are more crudely finished.[70] The external windows are almost all 18th-century in origin and made from Portland limestone.[71] The jagged remnants of the former palace walls jut out from the sides of the tower.[72] The moat, now dry, stretches away east from the tower, passing by the former landing stage for boats from the Thames, 6 metres (20 ft) long and made from ashlar stone.[73] The clearances of the post-war era mean that there are now few neighbouring buildings to the tower, and it is much more visible than in previous centuries.[74]

The ground floor of the tower is entered from the north, and is made up of two chambers, a larger room 7.5 by 4 metres (25 by 13 ft), a smaller turret room in the south-east corner, 4 by 3 metres (13.1 by 9.8 ft).[75] The windows in the main room are a mixture of early 18th-century designs, combined with a surviving large medieval window embrasure on the eastern side.[76] The main chamber has elaborate stone vaulting, considered by historian Jeremy Ashbee to be "one of the most impressive medieval interiors in London... an architectural masterpiece".[76] The vaulting features 16 carved Reigate Stone bosses, including grotesque heads, birds, flowers and the devil, some designed to form amusing visual illusions.[77] The ground floor is used by English Heritage as a gift shop and cafe.[78]

The first floor is reached by a 20th-century spiral staircase, and follows the same two-room design as the first floor.[79] It has a roof of groin-vaulted Portland stone, probably from the 18th century, and the windows are mostly 18th century in origin, with one 20th century reconstruction.[80] The iron door to the larger chamber carries the date of its installation, 1621, and its lock carries the letters "IR", standing for King James I.[81] The neighbouring room is barrel-vaulted in brick, with a recess in the wall that was originally a latrine, and the original 1719 iron-shutters on its north window.[82] The first floor contains an exhibit on the history of the UK Parliament.[78]

The spiral staircase to the second floor is original.[83] The floor continues the two-room design, and the roof, largely a post-war replacement with only a few surviving medieval timbers, is intended to resemble the original medieval design.[84] The fireplace and windows are original, as probably is the 14th-century wooden door to the floor.[83] Both the wall between the two rooms, and its stone doorway, were built in the 18th century.[85] The room contains a display on the history of the tower, and some of the original wooden foundations of the building.[86]

Notes

edit- ^ The pond referred to in this account may have been the moat of the Jewel Tower.[15]

- ^ Earlier scholarship had argued that the Jewel Tower began its new role as a document storage facility in 1621. Work in the early 21st century demonstrated that this began earlier, at the end of the 16th century.[24]

- ^ It is challenging to accurately compare 17th-century and modern financial sums. £166 in 1600 would be worth between £34,100 and £7,910,000 in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used.[25]

- ^ It is challenging to accurately compare 18th-century and modern financial sums. £870 in 1716 would be worth between £125,400 and £15,240,000 in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used.[25]

- ^ The records of the House of Commons were destroyed in the main fire. Only four buildings in Westminster Palace, including the Jewel Tower, survived the fire.[42]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Taylor 1991, p. 6

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 9–10

- ^ Stratford 2012, p. 3

- ^ Stratford 2012, p. 42

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1991, p. 10

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 10–11

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 12; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 5, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ a b Taylor 1991, p. 7

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 7, 9

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 9; Ashbee 2013, p. 7

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 9; Ashbee 2013, p. 9

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 9; Ashbee 2013, pp. 15, 25

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 3, 21

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 16

- ^ Jeremy Ashbee, "Divine Retribution at the Jewel Tower, Westminster", English Heritage, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 24

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 28; Ashbee 2013, p. 14

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 8, 10

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 12

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 12–13; Ashbee 2013, pp. 27–28

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 13; Ashbee 2013, p. 15

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 36; Taylor 1991, p. 13; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 5, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 36; Taylor 1991, p. 13; Ashbee 2013, p. 28; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 5, retrieved 13 September 2014; "Significance of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 36; Ashbee 2013, p. 28; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 5, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ a b Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ a b c Ashbee 2013, p. 8

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 15; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 5, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 15; Ashbee 2013, p. 11

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 16

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 16–17, 24; Ashbee 2013, p. 30

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 17; Wilson & Hurst 1957, pp. 159–160

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 17, 20

- ^ a b c Taylor 1991, pp. 20–21; Ashbee 2013, p. 33

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 12–13

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 21 ;Ashbee 2013, p. 11

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 8, 34

- ^ a b Taylor 1991, p. 24

- ^ a b Taylor 1991, p. 24; MacKinder 2006, p. 6

- ^ Smith 1807, pp. 33, 39

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 35

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 25; Ashbee 2013, p. 35; "History of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ "History of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014; "Significance of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 24–25; "History of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ "Significance of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Turner 1983, p. 51

- ^ Turner 1983, p. 51; Taylor 1991, p. 25

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 25

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1991, p. 26

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 27

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 26; "History of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 27; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 7, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 27; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, pp. 5–6, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 2, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ a b Ashbee 2013, p. 38

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 9, 12; Taylor 1991, p. 28; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, pp. 6–7, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Hansard (17 July 1956), "Jewel Tower, Westminster (Visitors)", Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 3, 17, 40

- ^ Wilson & Hurst 1957, pp. 159–160; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, pp. 6, 8, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ "Jewel Tower, Greater London Authority", English Heritage, 2007, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Wilson 1964, p. 270; Ashbee 2013, p. 17

- ^ Bridge 2011, p. 8; Greenwood & Maloney 1995, p. 353

- ^ Historic England. "The Jewel House (1003580)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "The Jewel House (or Tower) of the Palace of Westminster (1225529)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, p. 2, retrieved 13 September 2014; "The Jewel House (Or Tower) of the Palace of Westminster, Westminster", British Listed Buildings, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ "Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret's Church", UNESCO, 2008, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, pp. 17–18, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, pp. 11, 15, retrieved 13 September 2014; Atkins (2007), "The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey, including St. Margaret's Church, World Heritage Site Management Plan" (PDF), Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, pp. 78, 186, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 20; Batty, Lorna; Ashbee, Jeremy; Kemkeran-Smith, Annie; Lambarth, Sarah; Gomez, Natalie; Sydney, Alex; Allen, Kath; Davies, Nicole (2012–13), "Jewel Tower – Final Interpretation Plan" (PDF), English Heritage, pp. 8, 12, 14, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 14; "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 14

- ^ "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 28

- ^ Wilson 1964, p. 270

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 3

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 4, 40

- ^ a b Ashbee 2013, p. 4

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 6–7; "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ a b "Facilities at Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 12

- ^ Ashbee 2013, pp. 12–13; "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 13

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 13; "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ a b Ashbee 2013, p. 9

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 9; "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

- ^ Ashbee 2013, p. 11

- ^ "Description of the Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014; "Facilities at Jewel Tower", English Heritage, retrieved 13 September 2014

Bibliography

edit- Ashbee, Jeremy (2013). The Jewel Tower. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781848022393.

- Bridge, Martin (2011). "The Jewel Tower, Abingdon Street, Westminster, London: Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers, Scientific Dating Report, Research Report Series No. 109-2011". Research Report Series. London, UK: English Heritage. ISSN 2046-9799.

- Greenwood, Pamela; Maloney, Cath (1995). "Fieldwork Round-up". London Archaeologist. 7 (13): 333–354.

- MacKinder, Tony (2006). Proposed Ticket Office, 6–7 Old Palace Yard and The Jewel Tower Garden: An Archaeological Watching Brief Report. London, UK: Museum of London Archaeology Service.

- Smith, David L. (2012). "The House of Lords 1529–1629". In Jones, Clyve (ed.). A Short History of Parliament. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. pp. 29–41. ISBN 9781843837176.

- Smith, John Thomas (1807). Antiquities of Westminster; the Old Palace; St. Stephen's Chapel, (now the House of Commons). London, UK: J. T. Smith. OCLC 1864911.

- Stratford, Jenny (2012). Richard II and the English Royal Treasure. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843833789.

- Taylor, A. J. (1991) [1965]. The Jewel Tower: Westminster (2nd ed.). London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781850743637.

- Turner, Gerald L'E. (1983). Nineteenth-Century Scientific Instruments. Berkeley, US and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520051607.

- Wilson, David M.; Hurst, John G. (1957). "Medieval Britain in 1956". Medieval Archaeology. 1: 147–171. doi:10.1080/00766097.1957.11735387.

- Wilson, David M. (1964). "Medieval Britain in 1962 and 1963". Medieval Archaeology. 8: 231–299. doi:10.1080/00766097.1964.11735681.