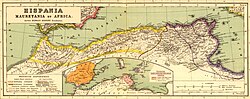

Mauretania (/ˌmɒrɪˈteɪniə, ˌmɔːrɪ-/; Classical Latin: [mau̯.reːˈt̪aː.ni.a])[5][6] is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It extended from central present-day Algeria to the Atlantic,[7][8] encompassing northern present-day Morocco, and from the Mediterranean in the north to the Atlas Mountains.[7] Its native inhabitants, of Berber ancestry, were known to the Romans as the Mauri and the Masaesyli.[1]

Mauretania | |

|---|---|

| 3rd century BC – 7th century AD[1] | |

Mauretania | |

| Status | Tribal Berber kingdoms (3rd century BC – 40 AD) Provinces of the Roman Empire (44 AD – 7th century AD) Independent kingdoms (431 AD[1] – 8th century) |

| Capital | Volubilis[2] Iol / Caesarea[3] |

| Common languages | Berber, Latin |

| Religion | Roman paganism, local beliefs, Christianity[4] |

| King | |

• 110–80 BC | Bocchus I |

• 25 BC - 23 AD. | Juba II |

• 20–40 AD | Ptolemy of Mauretania. |

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity |

• Established | 200 BC |

• client state of the Roman Empire | 25 BC |

• Division into Roman provinces | 44 AD |

• Disestablished | 44 AD |

| Today part of | Algeria Morocco Spain ∟Ceuta ∟Melilla |

In 25 BC, the kings of Mauretania became Roman vassals until about 44 AD, when the area was annexed to Rome and divided into two provinces: Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis. Christianity spread there from the 3rd century onwards.[9] After the Muslim Arabs subdued the region in the 7th century, Islam became the dominant religion.

Moorish kingdom

editMauretania existed as a tribal kingdom of the Berber Mauri people. In the early 1st century Strabo recorded Maûroi (Μαῦροι in Greek) as the native name of a people opposite the Iberian Peninsula. This appellation was adopted into Latin, whereas the Greek name for the tribe was Mauroúsii (Μαυρούσιοι).[10][11] The Mediterranean coast of Mauretania had commercial harbours for trade with Carthage from before the 4th century BC, but the interior was controlled by Berber tribes, who had established themselves in the region by the Iron Age.

King Atlas was a legendary king of Mauretania credited with inventing the celestial globe.[12] The first known historical king of the Mauri, Baga, ruled during the Second Punic War of 218–201 BC. The Mauri were in close contact with Numidia. Bocchus I ([fl.] 110 BC) was father-in-law to the redoubted Numidian king Jugurtha.

After the death of king Bocchus II in 33 BC Rome directly administered the region from 33 BC to 25 BC. Mauretania eventually became a client kingdom of the Roman Empire in 25 BC when the Romans installed Juba II of Numidia as their client-king. On his death in AD 23, his Roman-educated son Ptolemy of Mauretania succeeded him. The Emperor Caligula had Ptolemy executed in AD 40.[13] The Roman Emperor Claudius annexed Mauretania directly as a Roman province in AD 44, placing it under an imperial governor (either a procurator Augusti, or a legatus Augusti pro praetore).

Kings

edit

| Name | Reign | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlas | 6th Century BC | Mythical king of Mauretania[14] | |

| Bagas | fl. 225 BC | ||

| Bocchus I | c. 110 – c. 80s BC | ||

| Mastanesosus | c. 80s BC – 49 | ||

| Bogud | 49 – c. 38 BC | Co-ruler with Bocchus II | |

| Bocchus II | 49 – c. 33 BC | Co-ruler with Bogud | |

| Juba II | 25 BC – AD 23 | Roman client king | |

| Ptolemy | 20 – 40 AD | Last king of Mauretania Began reign as co-ruler with Juba II Assassinated by Caligula |

Roman province(s)

editIn the 1st century AD, Emperor Claudius divided the Roman province of Mauretania into Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Tingitana along the line of the Mulucha (Muluya) River, about 60 km west of modern Oran:

- Mauretania Tingitana was named after its capital Tingis (now Tangier); it corresponded to northern Morocco (including the current Spanish enclaves).

- Mauretania Caesariensis was named after its capital Caesarea (now Cherchell); and comprised western and central Algeria.

Mauretania gave the empire one emperor, the equestrian Macrinus. He seized power after the assassination of Caracalla in 217 but was himself defeated and executed by Elagabalus the next year.

Emperor Diocletian's Tetrarchy reform (293) further divided the area into three provinces, as the small, easternmost region of Sitifensis was split off from Mauretania Caesariensis.

The Notitia Dignitatum (c. 400) mentions them as still existing, two being under the authority of the Vicarius of the diocese of Africa:

- A Dux et praeses provinciae Mauritaniae et Caesariensis, i.e. a Roman governor of the rank of Vir spectabilis, who also held the high military command of dux, as the superior of eight border garrison commanders, each styled Praepositus limitis ..., followed by (genitive forms) Columnatensis, Vidensis, inferioris (i.e. lower border), Fortensis, Muticitani, Audiensis, Caputcellensis and Augustensis.

- A (civilian) Praeses in the province of Mauretania Sitifensis.

And, under the authority of the Vicarius of the diocese of Hispaniae:

- A Comes rei militaris of Mauretania Tingitana, also ranking as vir spectabilis, in charge of the following border garrison (Limitanei) commanders: and to whom three extraordinary cavalry units were assigned:

- Praefectus alae Herculeae at Tamuco

- Tribunus cohortis secundae Hispanorum at Duga

- Tribunus cohortis primae Herculeae at Aulucos

- Tribunus cohortis primae Ityraeorum at Castrabarensis

- Another Tribunus cohortis at Sala

- Tribunus cohortis Pacatianensis at Pacatiana

- Tribunus cohortis tertiae Asturum at Tabernas

- Tribunus cohortis Friglensis at the Fortress of Friglas or Frigias, near Lixus[15]

- Equites scutarii seniores

- Equites sagittarii seniores

- Equites Cordueni

- A Praeses (civilian governor) of the same province of Tingitana

Late Antiquity

editMauro-Roman Kingdom

editDuring the crisis of the 3rd century, parts of Mauretania were reconquered by Berber tribes. Direct Roman rule became confined to a few coastal cities (such as Septem in Mauretania Tingitana and Cherchell in Mauretania Caesariensis) by the late 3rd century.[16]

Historical sources about inland areas are sparse, but these were apparently controlled by local Berber rulers who, however, maintained a degree of Roman culture, including the local cities, and usually nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Roman Emperors.[17]

The Western kingdom more distant from the Vandal kingdom was the one of Altava, a city located at the borders of Mauretania Tingitana and Caesariensis....It is clear that the Mauro-Roman kingdom of Altava was fully inside the Western Latin world, not only because of location but mainly because it adopted the military-religious-sociocultural-administrative organization of the Roman Empire...[18]

In an inscription from Altava in western Algeria, one of these rulers, Masuna, described himself as rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum (king of the Roman and Moorish peoples). Altava was later the capital of another ruler, Garmul or Garmules, who resisted Byzantine rule in Africa but was finally defeated in 578.[19]

The Byzantine historian Procopius also mentions another independent ruler, Mastigas, who controlled most of Mauretania Caesariensis in the 530s. In the 7th century there were eight Romano-Moorish kingdoms: Altava, Ouarsenis, Hodna, Aures, Nemenchas, Capsa, Dorsale(ar) and Cabaon.[20]

The last resistance against the Arab invasion was sustained in the second half of the 7th century mainly by the Roman-Moorish kingdoms -with the last Byzantine troops in the region- under the leadership of the Christian king of Altava Caecilius, but later ended in complete defeat in 703 AD (when the queen Kahina died in battle).

Vandal kingdom

editThe Vandals conquered the Roman province beginning in the 420s.

The city of Hippo Regius fell to the Vandals in 431 after a prolonged siege, and Carthage also fell in 439. Theodosius II dispatched an expedition to deal with the Vandals in 441, which failed to progress farther than Sicily.[clarification needed] The Western Empire under Valentinian III secured peace with the Vandals in 442, confirming their control of Proconsular Africa. For the next 90 years, Africa was firmly under the Vandal control. The Vandals were ousted from Africa in the Vandalic War of 533–534, from which time Mauretania at least nominally became a Roman province once again.

The old provinces of the Roman Diocese of Africa were mostly preserved by the Vandals, but large parts, including almost all of Mauretania Tingitana, much of Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Sitifensis and large parts of the interior of Numidia and Byzacena, had been lost to the inroads of Berber tribes, now collectively called the Mauri (later Moors) as a generic term for "the Berber tribes in the province of Mauretania".

Praetorian prefecture of Africa

editIn 533, the Roman army under Belisarius defeated the Vandals. In April 534, Justinian published a law concerning the administrative organization of the newly acquired territories. Nevertheless, Justinian restored the old administrative division, but raised the overall governor at Carthage to the supreme administrative rank of praetorian prefect, thereby ending the Diocese of Africa's traditional subordination to the Prefecture of Italy (then still under Ostrogoth rule).

Exarchate of Africa

editThe emperor Maurice sometime between 585 and 590 AD created the office of "Exarch", which combined the supreme civil authority of a praetorian prefect and the military authority of a magister militum, and enjoyed considerable autonomy from Constantinople. Two exarchates were established, one in Italy, with seat at Ravenna (hence known as the Exarchate of Ravenna), and one in Africa, based at Carthage and including all imperial possessions in the Western Mediterranean. The first African exarch was the patricius Gennadius.[21]

Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Sitifensis were merged to form the new province of Mauretania Prima, while Mauretania Tingitana, effectively reduced to the city of Septem, was combined with the citadels of the Spanish coast (Spania) and the Balearic Islands to form Mauretania Secunda. The African exarch was in possession of Mauretania Secunda, which was little more than a tiny outpost in southern Spain, beleaguered by the Visigoths.

The last Spanish strongholds were conquered by the Visigoths in 624 AD, reducing "Mauretania Seconda" opposite Gibraltar to only the fort of Septem.

Religion

editChristianity is known to have existed in Mauretania as early as the 3rd century.[9] It spread rapidly in these areas despite its relatively late appearance in the region.[22] Although it was adopted in the urban areas of Mauretania Caesariensis, the hinterlands retained the Romano-Berber religion.[23]

See also

edit- Gaetuli tribe (namesake of Getulia)

- Mauretania Caesariensis

- Mauretania Tingitana

- Syphax

- Victor Maurus, a Christian Mauretanian martyr and saint

- Zeno of Verona

References

edit- ^ a b c "region, North Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. August 9, 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Volubilis".

- ^ "Iol - ancient city, Algeria". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 Aug 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ E. Wilhit, David (2017). Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition. Taylor & Francis. pp. 344–345. ISBN 9781135121426.

- ^ The Classic Latin Dictionary, Follett, 1957, only gives "Mauritania"

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ a b Phillip C. Naylor (7 May 2015). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-8108-7919-5.

- ^ Alan K. Bowman, Edward Champlin, Andrew Lintott (1996). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 597. ISBN 978-0-521-26430-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Early Christianity in Contexts: An Exploration across Cultures and Continents

- ^ Strabo, Geographica 17.3.2 (English translation): "Here dwell a people called by the Greeks Maurusii, and by the Romans and the natives Mauri, a populous and flourishing African nation, situated opposite to Spain" (οἰκοῦσι δ᾽ ἐνταῦθα Μαυρούσιοι μὲν ὑπὸ τῶν Ἑλλήνων λεγόμενοι, Μαῦροι δ᾽ ὑπὸ τῶν Ῥωμαίων καὶ τῶν ἐπιχωρίων, Λιβυκὸν ἔθνος μέγα καὶ εὔδαιμον, ἀντίπορθμον τῇ Ἰβηρίᾳ.).

- ^ Lewis and Short, Latin Dictionary, 1879, s.v. "Mauri".

- ^ Diodorus Siculus; Bib. IV, 27; Alexander Polyhistor, fr. 3, F.G.H. III, p. 212; John of Antioch, fr. 13, F.H.G. IV, p. 547.

- ^ Anthony A. Barrett, Caligula: The Corruption of Power (Routledge, 1989), pp. 116–117.

- ^ Rabasa, José (1993). Inventing America: Spanish Historiography and the Formation of Eurocentrism. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780806125398. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Villaverde Vega, Noé Tingitana en la antigüedad tardía, siglos III-VII: autoctonía y romanidad en el extremo occidente mediterráneo. Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia, 2001 ISBN 8489512949, 9788489512948 p. 275 (spanish)

- ^ Wickham, Chris (2005). Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400 - 800. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-921296-5.

- ^ Wickham, Chris (2005). Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400 - 800. Oxford University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-19-921296-5.

- ^ Noé Villaverde, Vega: "El Reino mauretoromano de Altava, siglo VI" (The Mauro-Roman kingdom of Altava) p.355

- ^ Aguado Blazquez, Francisco (2005). El Africa Bizantina: Reconquista y ocaso (PDF). p. 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07.

- ^ "Map showing the eight romano-berber kingdoms". Archived from the original on 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ^ Julien (1931, v.1, p.273)

- ^ Peasant and Empire in Christian North Africa, Leslie Dossey, page 25

- ^ Early Christianity in Contexts: An Exploration across Cultures and Continents

Further reading

edit- Aranegui, Carmen; Mar, Ricardo (2009). "Lixus (Morocco): from a Mauretanian sanctuary to an Augustan palace". Papers of the British School at Rome. 77: 29–64. doi:10.1017/S0068246200000039. S2CID 162724447.

- Papi, Emanuele (2014). "Punic Mauretania?". In Josephine Crawley Quinn, Nicholas C. Vella (ed.). The Punic Mediterranean. Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. Cambridge University. pp. 202–218. ISBN 978-1107055278.

- Roller, Duane W. (2003). The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene: Royal Scholarship on Rome's African Frontier. Routledge Classical Monographs. ISBN 0415305969.