The Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq (Arabic: نزهة المشتاق في اختراق الآفاق, lit. "The Excursion of One Eager to Penetrate the Distant Horizons"), commonly known in the West as the Tabula Rogeriana (lit. "The Book of Roger" in Latin), is an atlas commissioned by the Norman King Roger II in 1138 and completed by the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi in 1154. The atlas compiles 70 maps of the known world with associated descriptions and commentary of each specific location by Al-Idrisi.[1][2][3][4]

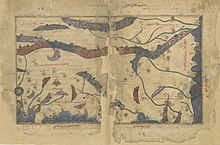

Map of al-Maghrib al-Aqsa and al-Maghrib al-Awsat (south-up) in MS arabe 2221, the oldest known surviving manuscript copy of Idrisi's Tabula Rogeriana. | |

| Author | Muhammad al-Idrisi |

|---|---|

| Media type | Atlas |

Creation of the Atlas

editAround 1138, the Norman King of Sicily, Roger II, invited Al-Idrisi, a Muslim geographer, to his court in Palermo, in search of help pursuing his political agenda. Sicily's vibrant multicultural environment led al-Idrisi to accept King Roger's invitation to his court. During the meeting, Al-Idrisi briefed Roger II on his familiarity and personal experiences traveling around North Africa and Western Europe, which prompted Roger II to commission an atlas from Al-Idrisi.[5] To produce the work, Al-Idrisi started gathering information for the maps by interviewing experienced travelers on their knowledge of the world, keeping "only that part... on which there was complete agreement and seemed credible, excluding what was contradictory."[1][5] King Roger II would occasionally participate in these interviews himself, reflecting his desire to compile information about his realm. Al-Idrisi drew inspiration from a number of sources, most of which are dated to the Golden Age of Islam during the Abbasid Caliphate, when scholarly work was flourishing in the Islamic world. Additionally, Al-Idrisi would send out agents to the different parts of the world represented in his map to fact-check the information given by the travelers.

Al-Idrisi's work was a significant departure from the "Atlas of Islam" tradition that preceded his work.[6] Al-Idrisi also derived map-making methods from the Balkhi school of Geography, a school which was founded during the 10th century in Baghdad under the Abbasid Caliphate.[7] It was from this school that he drew the scientifically rigorous and anthropologically detailed information that he incorporated into the atlas' creation. He also used some instruments King Roger II created to help calculate latitudes and longitudes.[8] This research process ultimately took some 15 years.

In 1154, just a few weeks before the king died, Al-Idrisi completed his atlas, producing a book with 70 sectional maps and a 300 lb (140 kg) silver disc engraved with the composite world map they formed. This would become known as the Nuzhat al-mushtaq fikhtiraq al-afaq, as well as the Book of Roger. This disc was made in accordance with Al-Idrisi's calculations of the circumference of the earth, and would lead to the later creation of a silver globe with the same map engraved on it.[8]

Description

editThe book, written in Arabic, is divided into seven "climatic zones" each of which is subdivided into ten sections. Each section is given its two-page spread map, for a total of 70 maps. The maps are oriented with North at the bottom, South at the top, with Mecca in the middle.[9] Each map was organized according to a coordinate system that, while inaccurate by modern standards, nonetheless ensured a level of rigor and consistency in scale from map to map.[10] Al-Idrisi added pages of commentary following each map he produced. The text incorporates descriptions of the physical, cultural, political, and socioeconomic conditions of each region.[2][11] This information was largely accurate, with inconsistencies being attributable to flawed accounts from the travelers interviewed.[10] The map and its details also convey the original intention of the map's patron. Areas in North Africa and Europe that were closer to Roger II's kingdom had more accurate information, while further areas such as Southeast Asia were less detailed. This reflects Roger II's desire to learn more about his domain and its surrounding areas, as well as Al-Idrisi's greater personal experience with these lands. The work showed, in al-Idrisi's words, "the seven climatic regions, with their respective countries and districts, coasts and lands, gulfs and seas, watercourses and river mouths".

It calculated the circumference to be 37,000 kilometres (23,000 mi) – an error of less than 10 percent – and it hinted at the concept of gravity. The different maps, when compiled together, made a rectangular map of the known world. In later editions, a smaller circular world map in which the south was drawn at the top and Mecca, at the center was added to the manuscript. Al-Idrisi's book came to be known as Kitab Rujar (Roger's Book). The original atlas and silver disc was destroyed in a rebellion headed by Matthew Bonnellus in 1160. The manuscript enjoyed wide popularity and use throughout the world. The medieval scholar Gabriel Sionita translated the book into Latin and printed it in Paris in 1619. The book was also translated into Spanish, German, Russian, Finnish, French, Italian, Austrian, and Swedish.[12] A total of 10 copies remain in various conditions, 5 of which are complete manuscripts.[2] Two of these are currently stored at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France including the oldest, which dates to about 1325, (MS Arabe 2221).[clarification needed] The discrepancies found between manuscripts from different locations are owed to the fact that al-Idrisi left multiple different drafts for the original work.[12] Another copy, made in Cairo in 1553, is in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Mss. Pococke 375). It was acquired in 1692.[13] The most complete manuscript, which includes the world map and all seventy sectional maps, is kept in Istanbul.[11]

Additionally, al-Idrisi created an abbreviated version of the book for Roger II's son, William II. This book, known as the "Little Idrisi," is still extant in multiple copies, and informs much of what scholars know today of al-Idrisi's original, extended work.[14]

Significance

editThis set of maps was profoundly influential for centuries to come. Many contemporary scholars hailed it as the greatest work of geography of the period.[15] Moreover, the atlas influenced later geographical works with its techniques, inspiring maps with similar levels of precision.

Additionally, Al-Idrisi's maps represented a shift in the philosophy of cartography. While the coordinates used were inaccurate by modern standards, they nonetheless illustrate that map-making was principally a scientific endeavor. Unlike previous cartographers, al-Idrisi aimed to be as accurate as possible and to provide as much reliable information about the various regions of the world, especially those contained in Roger II's realm. This contrasts heavily with prior Christian maps, which were solely based on the writings of the Bible. Islamic cartographers, while generally more accurate than their Christian counterparts, were still liable to use abstraction in their mapmaking. This made al-Idrisi's map one of a kind in its scope and ambitions, applying the techniques of the Balkhi School of Geography to an unprecedented scale and including detailed descriptions of all regions that it portrayed.[16]

In the 19th century, the manuscript experienced renewed interest and popularity with the rise of orientalism and interest in the East. Orientalists widely reprinted the book. In 1799, in Madrid, Jose Antonio Conde reprinted the section on Andalusia in its original Arabic with a Spanish translation. In 1828, Rosen Muller reprinted the section on Greater Syria and Palestine in Leipzig. In 1864, Reinhart Dozy reprinted the section containing information about Morocco, Sudan, Egypt, and Andalusia in Leon. These maps were used in a variety of activities, ranging from display to being taught and studied.[15]

On the work of al-Idrisi, S. P. Scott commented:

The compilation of Edrisi marks an era in the history of science. Not only is its historical information most interesting and valuable, but its descriptions of many parts of the earth are still authoritative. For three centuries geographers copied his maps without alteration. The relative position of the lakes which form the Nile, as delineated in his work, does not differ greatly from that established by Baker and Stanley more than seven hundred years afterwards, and their number is the same. The mechanical genius of the author was not inferior to his erudition. The celestial and terrestrial planisphere of silver which he constructed for his royal patron was nearly six feet in diameter, and weighed four hundred and fifty pounds; upon the one side the zodiac and the constellations, upon the other – divided for convenience into segments – the bodies of land and water, with the respective situations of the various countries, were engraved.[17]

Ten manuscript copies of the Book of Roger currently survive, five of which have complete text and eight of which have maps.[2] Two are in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, including the oldest, dated to about 1325. (MS Arabe 2221). Another copy, made in Cairo in 1553, is in the Bodleian Library in Oxford (Mss. Pococke 375). It was acquired in 1692.[13] The most complete manuscript, which includes the world map and all seventy sectional maps, is kept in Istanbul.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Houben, 2002, pp. 102–104.

- ^ a b c d Ahmad, 1992, pp. 156–161.

- ^ Al-Fora, Uthman (1983). "Al-Sharif Al-Idrisi and His Contributions to Geography" (PDF). King Saud University, Journal of the College of Education. 5: 159–185 – via King Saud University.

- ^ Editorial Board of Aljaranda (March 2016). "Travelers in Tarifa". Aljaranda. 89: 95–98 – via Dialnet.

- ^ a b Hasan, Muhammad ʻAbd al-Ghanī (1972). al-Sharīf al-Īdrīsī. Cairo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Antrim, Zayde (2018). Mapping The Middle East. London: Reaktion Books LTD. pp. 37–47. ISBN 978-1-78023-850-0.

- ^ Pastuch, Carissa (2022-01-13). "Al-Idrisi's Masterpiece of Medieval Geography | Worlds Revealed: Geography & Maps at The Library Of Congress". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ a b Ducne, Jean-Charles (December 1, 2011). "Les Coordonnees Geographiques De la Carte Manuscrite d'al-Idrs". Der Islam. 86 (2): 271–285. doi:10.1515/ISLAM.2011.022. S2CID 160351423.

- ^ Antrim, Zayde (2018). Mapping The Middle East. London: Reaktion Books LTD. pp. 37–47. ISBN 9781780238500.

- ^ a b Ducne, Jean-Charles (December 1, 2011). "Les Coordonnees Geographiques De la Carte Manuscrite d'al-Idrs". Der Islam. 86 (2): 271–285. doi:10.1515/ISLAM.2011.022. S2CID 160351423.

- ^ a b c Bacharach, 2006, p. 140.

- ^ a b Hasan, Muhammad ʻAbd al-Ghanī (1972). al-Sharīf al-Īdrīsī. Cairo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b The Book of Roger, BBC Online.

- ^ Parry, James V. 2004. "Mapping Arabia." Saudi Aramco World. January/February 2004. Pages 20–37.

- ^ a b Hasan, Muhammad ʻAbd al-Ghanī (1972). al-Sharīf al-Īdrīsī. Cairo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ducne, Jean-Charles (December 1, 2011). "Les Coordonnees Geographiques De la Carte Manuscrite d'al-Idrs". Der Islam. 86 (2): 271–285. doi:10.1515/ISLAM.2011.022. S2CID 160351423.

- ^ S. P. Scott (1904), History of the Moorish Empire, pp. 461-2

Sources

edit- Ahmad, Sayyid Maqbul (1992). "Cartography of al-Sharīf al-Idrīsī" (PDF). In Harley, John Brian; Woodward, David (eds.). Cartography in the traditional Islamic and south Asian societies. The history of cartography. Vol. 2.1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 156–174. ISBN 978-0-226-31635-2.

- Al-Fora, Uthman (1983). "Al-Sharif Al-Idrisi and His Contributions to Geography" (PDF). King Saud University, Journal of the College of Education. 5: 159–185 – via King Saud University.

- Antrim, Zayde (2018). Mapping the Middle East. London. ISBN 978-1-78023-850-0. OCLC 1004760121.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0

- Ducne, Jean-Charles (December 1, 2011). "Les Coordonnees Geographiques De la Carte Manuscrite d'al-Idrs". Der Islam. 86 (2): 271–285.

- Ḥasan, Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Ghanī. al-Sharīf al-Īdrīsī. N.p., 1972. Print.

- Houben, Hubert (2002). Roger II of Sicily: A Ruler between East and West. Cambridge: Cambridge University. ISBN 978-0-521-65208-7.

- Editorial Board of Aljaranda (March 2016). "Travelers in Tarifa". Aljaranda. 89: 95–98 – via Dialnet.

- Pastuch, Carissa (2022-01-13). "Al-Idrisi's Masterpiece of Medieval Geography | Worlds Revealed: Geography & Maps at The Library Of Congress". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

External links

edit- The World Maps of al-Idrisi

- Online exhibition, Bibliothèque nationale de France (French)

- View Online at the BNF (653 pages).