Serbian epic poetry (Serbian: Српске епске народне песме, romanized: Srpske epske narodne pesme) is a form of epic poetry created by Serbs originating in today's Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and North Macedonia. The main cycles were composed by unknown Serb authors between the 14th and 19th centuries. They are largely concerned with historical events and personages. The instrument accompanying the epic poetry is the gusle.

Serbian epic poetry helped in developing the Serbian national consciousness.[1] The cycles of Prince Marko, the Hajduks and Uskoks inspired the Serbs to restore freedom and their heroic past.[1] The Hajduks in particular, are seen as an integral part of national identity; in stories, the hajduks were heroes: they had played the role of the Serbian elite during Ottoman rule, they had defended the Serbs against Ottoman oppression, and prepared for the national liberation and contributed to it in the Serbian Revolution.[2]

History

editThe earliest surviving record of an epic poem related to Serbian epic poetry is a ten verse fragment of a bugarštica song from 1497 in Southern Italy about the imprisonment of Sibinjanin Janko (John Hunyadi) by Đurađ Branković,[3][4] however the regional origin and ethnic identity of its Slavic performers remains a matter of scholarly dispute.[5][6] From at least the Ottoman period up until the present day, Serbian epic poetry was sung accompanied by the gusle and there are historical references to Serb performers playing the gusle at the Polish–Lithuanian royal courts in the 16th and 17th centuries, and later on in Ukraine and Hungary.[7] Hungarian historian Sebestyén Tinódi wrote in 1554 that "there are many gusle players here in Hungary, but none is better at the Serbian style than Dimitrije Karaman", and described Karaman's performance to Turkish lord Uluman in 1551 in Lipova: the guslar would hold the gusle between his knees and go into a highly emotional artistic performance with a sad and dedicated expression on his face.[8] Chronicler and poet Maciej Stryjkowski (1547–1582) included a verse mentions the Serbs singing heroic songs about ancestors fighting the Turks in his 1582 chronicle.[9] Józef Bartłomiej Zimorowic used the phrase "to sing to the Serbian gusle" in his 1663 idyll Śpiewacy (Singers).[9]

In 1824, Vuk Karadžić sent a copy of his folksong collection to Jacob Grimm, who was particularly enthralled by The Building of Skadar. Grimm translated it into German, and described it as "one of the most touching poems of all nations and all times".[10][11]

Many of the epics are about the era of the Ottoman occupation of Serbia and the struggle for the liberation. With the efforts of ethnographer Vuk Karadžić, many of these epics and folk tales were collected and published in books in the first half of the 19th century. Up until that time, these poems and songs had been almost exclusively an oral tradition, transmitted by bards and singers. Among the books Karadžić published were:

- A Small Simple-Folk Slavonic-Serbian Songbook, 1814; Serbian Folk Song-Book (Vols, I-IV, Leipzig edition, 1823-8133; Vols. I-IV, Vienna edition, 1841-1862)

- Serbian Folk Tales (1821, with 166 riddles; and 1853)

- Serbian Folk Proverbs and Other Common Expressions, 1834.

- "Women's Songs" from Herzegovina (1866) - which was collected by Karadžić's collaborator and assistant Vuk Vrčević

These editions appeared in Europe when romanticism was in full bloom and there was much interest in Serbian folk poetry, including from Johann Gottfried Herder, Jacob Grimm, Goethe and Jernej Kopitar.[12]

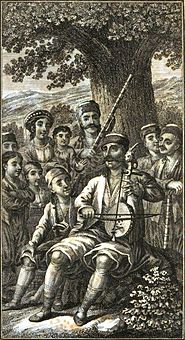

Gusle

editThe gusle (гусле) instrumentally accompanies heroic songs (epic poetry) in the Balkans.[13] The instrument is held vertically between the knees, with the left hand fingers on the neck.[13] The strings are never pressed to the neck, giving a harmonic and unique sound.[13] There is no consensus about the origin of the instrument, while some researchers believe it was brought with the Slavs to the Balkans, based on a 6th-century Byzantine source.[14] Teodosije the Hilandarian (1246–1328) wrote that Stefan Nemanjić (r. 1196–1228) often entertained the Serbian nobility with musicians with drums and "gusle".[15] Reliable written records about the gusle appear only in the 15th century.[14] 16th-century travel memoirs mention the instrument in Bosnia and Serbia.[14]

It is known that Serbs sang to the gusle during the Ottoman period. Notable Serbian performers played at the Polish royal courts in the 16th- and 17th centuries, and later on in Ukraine and in Hungary.[16] There is an old mention in Serbo-Croatian literature that a Serbian guslar was present at the court of Władysław II Jagiełło in 1415.[9] In a poem published in 1612, Kasper Miaskowski wrote that "the Serbian gusle and gaidas will overwhelm Shrove Tuesday".[9] Józef Bartłomiej Zimorowic used the phrase "to sing to the Serbian gusle" in his 1663 idyll Śpiewacy ("Singers").[9]

Corpus

editThe corpus of Serbian epic poetry is divided into cycles:

- Non-historic cycle (Неисторијски циклус/Neistorijski ciklus) - poems about Slavic mythology, characteristically about dragons and nymphs

- Pre-Kosovo cycle (Преткосовски циклус/Pretkosovski ciklus) - poems about events that predate the Battle of Kosovo (1389)

- Kosovo cycle (Косовски циклус/Kosovski ciklus) - poems about events that happened just before and after the Battle of Kosovo

- Post-Kosovo cycle (Покосовски циклус/Pokosovski ciklus) - poems about post-Battle events

- Cycle of Kraljević Marko (Циклус Краљевића Марка/Ciklus Kraljevića Marka)

- Cycle of hajduks and uskoks (Хајдучки и ускочки циклус, Хајдучке и ускочке песме) – poems about brigands and rebels

- Poems about the liberation of Serbia and Montenegro (циклус ослобођења Србије, Песме о ослобођењу Србије и Црне Горе) - poems about the 19th-century battles against the Ottomans

- Unsorted (Неразврстане/Nerazvrstane) – poems that do not belong to any of the cycles mentioned above

Poems depict historical events with varying degrees of accuracy.

Dying Pavle Orlović is given water by a maiden who seeks her fiancé; he tells her that her love, Milan, and his two blood-brothers Miloš and Ivan are dead.

—taken from the Serb epic poem

Notable people

edit- Benedikt Kuripečič (16th century), diplomat who traveled through Ottoman Bosnia and Serbia in 1530 and recorded that epic songs about Miloš Obilić are popular not only among Serbs in Kosovo but also in Bosnia and Croatia. He also recorded some legends about the Battle of Kosovo.[17]

- Dimitrije Karaman (fl. 1551), oldest known Serbian gusle player

- Avram Miletić (1755–after 1826), merchant and songwriter best known for writing the earliest collection of urban lyric poetry in Serbian.

- Old Rashko, one of the most important sources of epic poetry recorded by Vuk Karadžić.

- Filip Višnjić (1767–1834), Serbian guslar dubbed the "Serbian Homer" both for his blindness and poetic gift.

- Tešan Podrugović (1783–1815), Serb hajduk, storyteller and guslar who participated in the First Serbian Uprising and was one of the most important sources for Serbian epic poetry.

- Živana Antonijević (d. 1822), known as "Blind Živana", one of the favorite female singers of Vuk Karadžić.

- Vuk Karadžić (1787—1864) was a Serbian philologist and linguist who was the major reformer of the Serbian language. He deserves, perhaps, for his collections of songs, fairy tales, and riddles to be called the father of the study of Serbian folklore.

- Vuk Vrčević (1811-1882), collector of lyric poetry

- Petar Perunović (1880–1952), known as "Perun", famous guslar who performed for Nikola Tesla and the first to record Serbian epic poetry in a studio.

- Đuro Milutinović the Blind (1774–1844), guslar at Serbian court.

Characters

edit- Medieval era

- Tsar Dušan, Emperor

- Prince Lazar, Prince and legendary Emperor

- Pavle Orlović, knight

- Milan Toplica, knight

- Ivan Kosančić, knight

- Jugović brothers, including Boško Jugović

- Beg Kostadin

- Miloš Vojinović

- Voivode Prijezda

- Mali Radojica, hajduk

- Deli Radivoje

- "Zmaj Ognjeni Vuk" (Vuk the Fiery Dragon), based on Vuk Grgurević, the Serbian Despot (r. 1471–85)

- Ailing Dojčin, possibly based on despots John VII Palaiologos and Andronikos Palaiologos

- Relja the Winged

- Pop Milo Jovović

- Bajo Pivljanin

- Stari Vujadin

- Alil-Aga

- Sibinjanin Janko

- Jug Bogdan

- Janko od Kotara

- Starina Novak (partly)

- Musa Kesedžija, enemy of Kraljević Marko, he is the result of merging several historical people including Musa Çelebi son of Bayezid I and Musa from the Muzaka Albanian noble family while Jovan Tomić believes he is based on the supporter of Jegen Osman Pasha

- Djemo the Mountaineer, enemy of Kraljević Marko, a member of Muzaka noble family (Gjin Muzaka) or maybe Ottoman military person Jegen Osman Pasha

- General Vuča, enemy of Kraljević Marko, Tanush Dukagjin, a member of Dukagjini noble family or Prince Eugene of Savoy or Peter Doci

- Philip the Magyar, enemy of Kraljević Marko, Pipo of Ozora, an Italian condottiero, general, strategist and confidant of King Sigismund of Hungary.

- Arnaut Osman

Hajduk cycle

- Ognjen Hadzovic, hajduk, main character in Ženidba Hadzovic Ognjena.[18]

- Srbin Tukelija, hajduk, main character in Boj Arađana s Komadincima.[19]

Many other heroes of Serbian epic poetry are also based upon historical persons:

- Strahinja Banović — Đurađ II Stracimirović Balšić

- Jug Bogdan — Vratko Nemanjić

- Beg Kostadin — Constantine Dragaš

- Sibinjanin Janko — John Hunyadi

- Petar Dojčin — Petar Doci

- Maksim Crnojević — Staniša Skenderbeg Crnojević

- Bajo Pivljanin - Bajo Nikolić

- Mihajlo Svilojević — Michael Szilágyi

- Janko od Kotara - Janko Mitrović

- Manojlo Grčić - Manuel I Komnenos

- Relja the Winged - Hrelja

- Grujica Žeravica

Some heroes are paired with their horses, such as Prince Marko—Šarac, Vojvoda Momčilo—Jabučilo (a winged horse), Miloš Obilić—Ždralin, Damjan Jugović—Zelenko, Banović Strahinja—Đogin, Hajduk-Veljko—Kušlja, Jovan Kursula—Strina, Srđa Zlopogleđa—Vranac.[20]

Excerpts

editThere two pines were growing together,

and among them one thin-topped fir;

neither there were just some two green pines

nor among them one thin-topped fir,

but those two were just some two born brothers

one is Pavle, other is Radule

and among them little sis' Jelena.

- (Kraljević Marko speaks: )

"I'm afraid that there will be a brawl.

And if really there will be a brawl,

Woe to one who is next to Marko!"

"Thou dear hand, oh thou my fair green apple,

Where didst blossom? Where has fate now plucked thee?

Woe is me! thou blossomed on my bosom,

Thou wast plucked, alas, upon Kosovo!"

"Oh my bird, oh my dear grey falcon,[21]

How do you feel with your wing torn out?"

"I am feeling with my wing torn out

Like a brother one without the other."

Modern example of Serbian epics as recorded in 1992 by film director Paweł Pawlikowski in a documentary for the BBC Serbian epics; an anonymous gusle singer compares Radovan Karadžić, as he prepares to depart for Geneva for peace talk, to Karađorđe, who had led the First Serbian Uprising against the Turks in 1804:[22]

"Hey, Radovan, you man of steel!

The greatest leader since Karađorđe!

Defend our freedom and our faith,

On the shores of Lake Geneva."

Quotes

edit

Jacob GrimmThe ballads of Serbia occupy a high position, perhaps the highest position, in the ballad literature of Europe. They would, if well known, astonish Europe... In them breathes a clear and inborn poetry such as can scarcely be found among any other modern people.

Charles SimicEveryone in the West who has known these poems has proclaimed them to be literature of the highest order which ought to be known better.

Modern Serbian epic poetry

editEpic poetry is recorded still today. Some modern songs are published in books or recorded, and under copyright, but some are in public domain, and modified by subsequent authors just like old ones. There are new songs that mimic old epic poetry, but are humorous and not epic in nature; these are also circulating around with no known author. In the latter half of the 19th century, a certain MP would exit the Serbian parliament each day, and tell of the debate over the monetary reform bill in the style of epic poetry. Modern epic heroes include: Radovan Karadžić, Ratko Mladić and Vojislav Šešelj. Topics include: Yugoslav wars, NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, and the Hague Tribunal.

Popular modern Serbian epic performers, guslari (Guslars) include: Milomir "Miljan" Miljanić, Đoko Koprivica, Boško Vujačić, Vlastimir Barać, Sava Stanišić, Miloš Šegrt, Saša Laketić and Milan Mrdović.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Dragnich 1994, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Wendy Bracewell (2003). "The Proud Name of Hajduks". In Norman M. Naimark; Holly Case (eds.). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-8047-8029-2.

- ^ Matica Srpska Review of Stage Art and Music. Matica. 2003. p. 109.

...родовског удруживања и кнежинске самоуправе, а према механизму фолклорне рецепци^е садржаја званичне културе, српске епске јуначке песме, посебно бугарштице, прва је забележена већ 1497. године, чувају успомене и ...

- ^ Milošević-Đorđević, Nada (2001). Srpske narodne epske pesme i balade. Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva. p. 10. ISBN 9788617088130.

Крајем XV века, 1497. године, појављује се за сада први познати запис од десет бугарштичких стихова, које је у свом епу забележио италијански ... Јанка, ердељског племића (чије је право име Јанош Хуњади) у тамници српског деспота Ђурђа Бранковића.

- ^ Šimunović, Petar (1984), "Sklavunske naseobine u južnoj Italiji i naša prva zapisana bugaršćica", Narodna Umjetnost: Croatian Journal of Ethnology and Folklore Research (in Croatian), 21 (1), Institute of Ethonology and Folklore Research: 56–61 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske

- ^ Bošković-Stulli, Maja (2004), "Bugarštice", Narodna Umjetnost: Croatian Journal of Ethnology and Folklore Research (in Croatian), 41 (2), Institute of Ethonology and Folklore Research: 38–39 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske

- ^ Pejovic, Roksanda (1995). "Medieval music". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- ^ Petrović 2008, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e Georgijević 2003.

- ^ Alan Dundes (1996). The Walled-Up Wife: A Casebook. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-299-15073-0. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ Paul Rankov Radosavljevich (1919). Who are the Slavs?: A Contribution to Race Psychology. Badger. p. 332. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

skadar.

- ^ Milošević-Đorđević 1995.

- ^ a b c Ling 1997, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Bjeladinović-Jergić 2001, p. 489.

- ^ Vlahović 2004, p. 340.

- ^ Pejovic, Roksanda (1995). "Medieval music". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- ^ Pavle Ivić (1996). Istorija srpske kulture. Dečje novine. p. 160. ISBN 9788636707920. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

Бенедикт Курипечић. пореклом Словенаи, који између 1530. и 1531. путује као тумач аустријског посланства, у свом Путопису препричава део косовске легенде, спомиње епско певање о Милошу Обилићу у крајевима удаљеним од места догађаја, у Босни и Хрватској, и запажа настајање нових песама.

- ^ Karadžić 1833, pp. 265–271.

- ^ Karadžić 1833, pp. 271–276.

- ^ Политикин забавник 3147, p. 4

- ^ Black Lamb and Grey Falcon by Rebecca West is the title of one of the best-known books in English on the subject of Yugoslavia.

- ^ Judah, Tim (1997). The Serbs - History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Sources

edit- Bjeladinović-Jergić, Jasna (2001). Зборник Етнографског музеја у Београду: 1901-2001. Етнографски музеј. pp. 489–. ISBN 9788678910081.

- Dragnich, Alex N. (1994). Serbia's Historical Heritage. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-244-6.

- Georgijević, Krešimir (2003) [1936]. "Српскохрватска народна песма у пољској књижевности: Студија из упоредне историје словенских књижевности". Belgrade: Rastko; Српска краљевска академија.

- Karadžić, Vuk S. (1833). Narodne srpske pjesme. Vol. 4. Vienna: štamparija Jermenskog manastira.

- Ling, Jan (1997). "Narrative Song in the Balkans". A History of European Folk Music. University Rochester Press. pp. 86–90. ISBN 978-1-878822-77-2.

- Milošević-Đorđević, Nada (1995). "The oral tradition". The history of Serbian Culture. Rastko.

- Petrović, Sonja (2008). "Oral and Written Art Forms in Serbian Medieval Literature". In Mundal, Else; Wellendorf, Jonas (eds.). Oral Art Forms and Their Passage Into Writing. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 85–108. ISBN 978-87-635-0504-8.

- Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815624448.

- Vlahović, Petar (2004). Serbia: the country, people, life, customs. Ethnographic Museum. ISBN 978-86-7891-031-9.

Further reading

edit- Burić, Ranko (1989). "KOSOVSKI CIKLUS" (PDF). Etnološke sveske. 10: 119–125.

- Jakobson, Roman (1966). Slavic Epic Studies. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-088958-1.

- Locke, Geoffry N. W. (1997). The Serbian epic ballads: an anthology. Nolit. ISBN 9788619021562.

- Meredith, Owen (1861). Serbski Pesme, Or, National Songs of Serbia. London: Chapman and Hall. ( Public domain)

- Noyes, George Rapall; Bacon, Leonard (1913). Heroic Ballads of Servia. Boston: Sherman, French & Company. (Public Domain)

- Perić, Dragoljub Ž. (2013). "Temporal formulas in Serbian oral epic songs". Balcanica. 44 (44): 159–180. doi:10.2298/BALC1344159P.

- Petrović, Sonja (2005). "Charity, good deeds and the poor in Serbian epic poetry". Balcanica. XXXVI (36): 51–71. doi:10.2298/BALC0536051P.

- Petrovitch, Woislav M. (2007) [1915]. Hero Tales and Legends of the Serbians. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60206-081-4.

- Petrovitch, Woislav M. (1915). "Hero Tales and Legends of the Serbians". (illustrated) ( Public domain)

- Miodrag Stojanović; Radovan Samardžić (1984). Хајдуци и клефти у народном песништву. Српска академија наука и уметности, Балканолошки институт.

External links

edit- Lew, Mark D. (1999). "Serbian Epic Poetry".

- The Battle of Kosovo - Serbian Epic Poems Preface by Charles Simic Swallow Press/Ohio University Press, Athens 1987

- Audio