The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2023) |

LGBTQ theatre (also known as gay theatre, lesbian theatre or queer theatre) is theatre that is based on the lives of gay and lesbian people and gay and lesbian culture. Some LGBTQ theatre is specifically about the experiences of gay men or lesbian women.[1] Collectively, LGBTQ theatre forms part of LGBTQ culture.

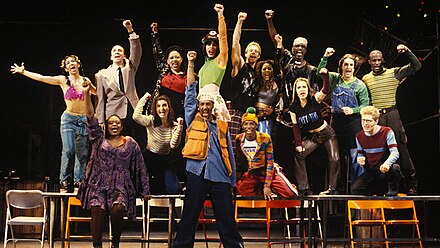

Famous examples of LGBTQ theatre include the musical Rent by Jonathan Larson and the play Bent by Martin Sherman.

History of LGBTQ theatre

editAncient Greece

editIn Ancient Greece, homosexuality was considered normal and was even promoted in some settings. In Thebes, it was actively practiced and legally "incentivized".[2] The theater was considered a "tool to promote society's values"[3] and homosexuality was showcased in these plays. In Aristophanes' play, The Knights, the protagonist Agoracritus, openly admits to having been a "passive" partner.[4] In another one of Aristophanes' plays, Thesmophoriazusae, the character of Euripides, directs what could be seen as homophobic comments to his colleague, Agathon. Other characters in the play ridicule his behavior and point out their obsession with masculinity.[5] As the play is a comedy, many have interpreted the character as humorous. A theorized example of homosexuality in the Iliad is Achilles and Patroclus. Historians and contemporaries theorize that the characters had a more than platonic relationship.[6] The story of Achilles and Patroclus was portrayed in William Shakespeare's play, Troilus and Cressida.

Before 20th century

editHomosexuality was not significantly notarized in the centuries following the downfall of Ancient Greece and leading up until the 20th century. Theatre during that time period is not known to have any LGBTQ themes or ideas. Homosexuality was known and written about starting closer to the 20th century. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the idea of homosexuality was very stigmatized around the world. In the UK, the punishment for any act of sodomy was execution.[7] Additionally, there was a shift in the classification of homosexual men, as sodomy was no longer an act, but an identity.[7] During an era where homosexuality was criminalized, plays about the lives of gay men, were not present. However, since the era of Shakespeare, men were used to playing women's roles in theatre.[8] Women were seen as unfit to play characters in plays, so men would dress up like women to portray female characters.[9] This continued until the 19th century when the popularization of opera allowed women to access the world of theater.[10] As the Cafe grew in popularity, its owner decided to add poetry readings, and with their popularity, plays were also added. Cafe Cino was the birthplace of Off-Off Broadway, where The Madness of Lady Bright, the first admittedly LGBTQ play was performed.[10] The show was the longest-running at the Cafe Cino and was performed over 200 times to packed houses.[11] Four years later, the first LGBTQ play to be on Off-Broadway, was performed, The Boys in the Band.[10] This play garnered serious attention, as it was performed at a legitimate playhouse. Although reactions were mixed, The Boys in the Band cemented a legacy for itself and is considered one of the classic LGBTQ plays.[12] By 1983, the first LGBTQ play on Broadway was performed. La Cage aux Folles, was a musical based on the 1978 movie, La Cage aux Folles.[13] The story surrounds a middle-aged homosexual couple who learns how deep their love truly is after navigating obstacles. The play was groundbreaking because of the characterization of its main characters, one being the owner of a Saint-Tropez drag club, and the other its star performer. The play received high praise and was performed 1,761 times, and was revived in the fall of 2004.[13]

Late 20th-21st century

editThe mid-20th century saw the rise of LGBTQ plays and the popularization of them. Even with the stigma around the LGBTQ community, especially with the rise in the AIDS epidemic, LGBTQ pride and media were becoming mainstream. Plays, TV shows, and films about LGBT-identifying people were becoming common pieces of media. Popular musicals began to pop up throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the most famous being Rent, which came out in the 1990s. The musical is set in the early 1990s, and it centers around a group of New Yorkers, as they struggle with their careers, love lives, and the AIDS epidemic. The play was seen as groundbreaking and was performed over 5,000 times and ran for 12 years.[14] The legacy that Rent produced allowed for a range of LGBTQ productions to be performed across the world. One of the most notable productions that came in the wake of Rent was The Book of Mormon, a musical created by the creators of the hit TV show, South Park. The musical follows two inexperienced Mormon missionaries as they preach to a Ugandan village.[15] The musical encroached upon the boundaries of Mormonism, a sect of Christianity that is primarily known for having conservative viewpoints, such as believing in traditional marriage between a man and a woman.[16] The musical received support from the LGBTQ community because of its willingness to cross the lines that had previously not been in musical theatre.

Legacy

editThe history of LGBTQ theatre has inspired many plays and musicals over the years. As the genre grew, playwrights and screenwriters cited the "classics" as their reference for their projects. A prominent play that has been cited as "influential", was one of the first, The Boys in the Band.[10] The play became prominent throughout the U.S. when it came out for being the "most frank description of being gay", and instantly received praise and criticism.[17] The play, for many, was cited as their first time being exposed to homosexuality. In 2018, an article by the New York Times came out, where people submitted stories about how they heard about The Boys in the Band, and how it affected them. The play was revived for its fiftieth anniversary in 2018 with a cast including Matt Bomer, Jim Parsons, and Zachary Quinto.[10] The play's producer Ryan Murphy, stated "The guys that who are the leads, are the first generation of gay actors who said, ‘We’re going to live authentic lives and hope and pray our careers remain on track’ — and they have. I find that profound." The play was brought back with two other gay "classics", Angels in America and Torch Song Trilogy.[10]

LGBTQ theatre around the world

editBackground

editLGBTQ theatre has become much more popular in the last century, including in North America, Asia, and Europe. However, not all people are accepting of this use of theatre. In the past and present there has been a lot of controversy over identifying as LGBT, and LGBTQ influence to the public. Over the past few centuries, LGBTQ representation has been much more apparent all over the world, including places like the U.S., with things like pride parades and many forms of representation, but there are also places like Asia where there is a plentiful number of LGBTQ identifying individuals who are lacking representation because of the place in the world and the government control over things like LGBTQ rights and representation. The idea of being an LGBTQ individual is still not accepted as a whole yet, in most countries around the world, so the likelihood of LGBTQ theatre being a part of culture in many countries is slim. Whereas places like Europe, Australia, and the U.S., are far more likely to have many more resources for expression than places like Asia and Africa.

North America

editIn the U.S., LGBTQ theatre is relatively well known and has been for the past few decades. It has been around for longer than that but suffered a lot of controversy.[18] Some of these shows include Rent in 2005 and written by Chris Columbus, it is an LGBTQ story about that contracting of AIDS, and the controversy surrounding it, or The Prom by Chad Beguelin, it follows a group of Indiana teens trying to their lesbian friend because she was banned from bringing her girlfriend to the prom, due to them living in a conservative town. These musicals/plays portray LGBTQ characters and provide representation to their audiences. The U.S. has been a hub for LGBTQ representation and this is very apparent through LGBTQ theatre. This includes more than just Broadway there is a plentiful amount of smaller theatres that premiere LGBTQ centered plays all around the U.S. Playbill posted the article, and stated, "Diversionary Theatre was founded in 1986 to provide quality theatre for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities. The mission of the theatre is to provide an inspiring and thought-provoking theatrical platform to explore complex and diverse LGBTQ stories."[10] This theatre and many other smaller theatres have similar missions, their missions being to present diversity among LGBTQ individuals and to educate people about the community.

Europe

editEurope, similar to the U.S., has a more progressive view on LGBTQ theatre and has been accepting of the LGBTQ community while also providing representation. In Europe LGBTQ theatre can date back all the way to the 6th century BC in Ancient Greece. Although technically it is not classified as LGBT, men would dress as women, because women were not yet allowed in the theatre industry, and this can be seen as a form of drag.[12] Even Shakespeare produced plays that may be seen by some, as equivalent to LGBTQ plays currently. Current LGBTQ theatre is more accepted in Europe but in past centuries there were many restrictions regarding what could be put on stage and what could not, causing a lot of restrictions specifically on LGBTQ theatre. This was apparent all the way up until the mid-1900s specifically in the UK. Lord Chamberlain was a large part of these restrictions, he was a prominent figure in controlling theatre in the UK during the 1900s.[12] He was the highest-ranking member in The Royal Household of the United Kingdom, meaning he had the power to censor or grant, or not grant licenses to certain plays.[19] However, later some of those restrictions would be lifted and in the 21st century many LGBTQ plays could be seen in theatre.

Asia

editAsia, in comparison to many other continents, LGBTQ theatre is not as prominent, and much less supported.[20] In the past, specifically, Taiwan has gone through many changes and challenges in government, including, being under martial law, and events like colonization visible in the 1800s, which included the LGBTQ community. In Taiwan conservatism is still widely present which represses many citizens in general but especially those of the LGBTQ community.[20] Not only has LGBTQ identity been questioned in Taiwan but so has individual identity because they had been under so much restriction for so long. Consequently, queer theater was not prevalent until post-martial law. But during this time it did become very popular.[20]

Many Taiwanese queer theatres had similar themes, those being queer identification and, gender and sexuality. A very important person during this time in LGBTQ theatre was Lai Sheng-Chuan, who would end up bringing LGBTQ theatre to light, by influencing his work from the government, by criticizing them, as well as dreams that many Taiwanese people wished to achieve because the martial law was abolished.[20]

The first known queer theater in Taiwan was Maoshi established in 1988 by Tian ChiYuan who would end up dying from AIDS. He would use theatre to fight homophobia as well as the stigma people had on AIDS, during times of extreme conservatism.[20] His goal was to break social norms and to bring light to people of the LGBTQ community. Some of Tian ChiYuan most known plays are adaptations of whitewater and Legend of the white snake, which were both centered around homoerotic love, which was an unseen public topic during the 1990s.[20] Even after Tian ChiYuan's death, people would continue to create adaptations of whitewater because of its symbolism of queer trauma and people wanted that legacy to continue, because of his amazing influence in LGBTQ theatre.

Backlash to LGBTQ theater

editBackground

editLGBT theater has faced backlash ranging from audiences to critics for over a century. The most well-known backlash against LGBTQ theater is The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oscar Wilde received backlash on his well-known novel from critics and readers who called the work "unclean" and "contaminated" for its LGBT themes.[21]

LGBTQ theater was also faced with backlash in the 1970s as well like when the play The Boys in the Band was staged in the Black Box Theater at the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center in March 1970. The Fulton County Commission threatened to cut public funding due to its portrayal of gay life, labeling it "filthy content."[22] Nevertheless, the play continued to be staged for two weeks and would be staged again at Buckhead Theatre in 1976.

A similar backlash was faced in 2016 when a bomb threat disrupted a Moscow, Russia screening of a transgender film.[23] Similar events occurred only 3 years before this when screenings of several films at the LGBTQ theater festival Side by Side were disrupted in Moscow by bomb threats.[24] The festival's screenings were disrupted on numerous occasions, and has been coming back in Russia due to a law "against gay propaganda among minors."[25]

Like this, LGBTQ theatre has faced backlash for many years due to the nature of its content about gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer folks, and this still is occurring to the present day.

Incidents

editThe backlash against LGBTQ theater ranges from physical to financial threats and is a big part of the barriers that LGBTQ theater faces due to the nature of its content. These backlashes are often because of what LGBTQ theater is about — showing the lives and stories of LGBTQ folks living their lives, such as musicals like Rent and plays like Angels in America.[26][27] Even among these threats that often threaten one's life and the whole theater, LGBTQ theater continues to work its best in order to put the show on board and show people the lives and experiences that folks face, especially those related to LGBTQ themes.

Physical threats

editThere have been many threats that LGBTQ theater faced physically, such as bomb threats. In June 2018, the Gay Men's Chorus concert was canceled due to a bomb threat at Alex Theatre, and hundreds were forced to evacuate due to this threat.[28][29]

Financial and cancellation threats

editThere have been many backlashes against LGBT theater relating to the withdrawal of financial support as well as canceling the show itself.

Financial threats are the most common in the LGBTQ theater and threaten many stages where LGBTQ performances can be held. In July 2023, House Republicans voted to eliminate funding to LGBTQ community centers, accusing the centers of having in place "supporting communism, drag shows, and the administration of hormone replacement therapy to young people."[30] Many other politicians were against this amendment by calling the decision "one of the most obvious and disgusting examples of bigotry that I’ve seen in my career and in my life."[30] Because of these financial withdrawals of financial support in LGBTQ community centers, LGBTQ theater also faces backlash as LGBTQ community centers are very closely related to LGBTQ theater and often provide places to stage a community LGBTQ theater. With the funds getting cut in the community centers, it causes much fewer stages to exist in LGBTQ theater.

The cancellation of shows occurs most often in school plays, where student actors often have to cancel shows because of school administration. For example, in Florida’s Duval County Public Schools in January 2023, administrators stopped production of the play Indecent, which detailed a love affair between two women, due to its "mature content."[31] In February 2023, Indiana’s Northwest Allen County Schools canceled a production of the play Marian after adults protested over its depiction of a same-sex couple and a non-binary character.[31]

There were also threats over the cancellation of shows in non-school plays as well. One of the well-known cancellation threats was the Angels in America premiere in Charlotte, North Carolina. In this premiere, the Angels in America show was on the brink of getting the entire show canceled due to protests from locals and barely managed to get confirmed to put the show on play merely a few hours before the show was supposed to start. This, in turn, made the show more successful as more people gathered to see what the fuss was all about, and sold out the tickets.[32] But although this is a successful case of an LGBTQ theater not getting canceled and being able to premiere, it still shows the threats that LGBTQ theater faces because of the nature of LGBTQ theater.

As such, LGBTQ theater still faces many backlash and struggles to be presented in the same way that other theaters are presented.

Backlash outside of America

editAround the world

editThere are also backlashes against LGBTQ theater around the world, and these backlashes often differ due to the cultural aspects and the laws and regulations set in place.[33] Depending on the country, the backlashes may range from simple protests to arrests due to breaking the laws set in place there.

Russia

editIn November 2022, a theater in the Southern Russian city of Novosibirsk was canceled just days after local Culture Ministry authorities stated that they would investigate whether or not the performance violated anti-LGBTQ legislation set in place in 2013.[34] Although the Siberian Theater announced that the play was canceled due to technical difficulties, the show's cancellation came only days after many posts emerged on social media to investigate whether the show broke the Russian laws banning the "promotion of non-traditional sexual relations with minors."[35] The show was canceled just 20 minutes before the start, and while authorities declined to say whether the cancellation was due to the announced investigation, many believe that the cancellation was due to the relationship of two characters in the show, where they, at one point, act out a scene from The Princess and The Ogre as two men.

Hungary

editIn June 2018, the Hungarian State Opera canceled over a dozen performances of the musical Billy Elliot after a newspaper columnist accused the production of being "gay propaganda."[36] A June 1 column by Zsofia N. Horvath in the conservative paper Magyar Idők claimed that this musical involving a boy searching to become a ballet dancer exposes young audience members to "unrestrained gay propaganda," going "against the objectives of the state...in a situation where the population is already aging and decreasing." This caused 15 of the shows to be canceled.[37]

Notable LGBTQ theatre people

editBelow is a collection of multiple notable LGBTQ actors,[38][39] directors, and playwrights[40] It contains different people from throughout the eras, going as far back as 1854, and to recent, more modern roles.

One of the first and most notable LGBTQ playwrights was Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde, or Oscar Wilde.[41] Born October 16, 1854, in Dublin, Ireland, he is known for works such as The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest.[41] Due to his homosexuality at that time, he was arrested and sent to prison.[41]

Tennessee Williams, or Thomas Lanier Williams III, was born March 26, 1911, and is known as a very notable, openly gay playwright.[42] He wrote plays such as The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.[42] Alongside plays, Williams also wrote short stories, poetry and some memoirs, and was also inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.[42]

Edward Franklin Albee III was born March 12, 1928, and wrote many plays throughout his life, some notable ones including The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?, Three Tall Women, and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?.[43] He was openly gay and never hid his homosexuality.[43]

Tony Kushner was born July 16, 1956, and lives his life as an openly gay American playwright.[44] He is best known for his work on Angels in America, which won a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award, he also received the National Medal of Arts from Barack Obama in 2013.[44]

Mart Crowley was born August 21, 1935, and is best known for his work on the play Boys in the Band, which had gay themes.[45] Other works include Remote Asylum and A Breeze from the Gulf.[45]

John Waters was born April 22, 1946, and is known for being an openly gay actor, playwright, filmmaker, and his iconic pencil mustache.[46] He has appeared in films such as Seed of Chucky and Suburban Gothic, but also wrote and directed the film Hairspray, which was later turned into a Broadway musical.[46]

Harvey Fierstein was born June 6, 1954, and is an openly gay actor and playwright.[47] He is mostly known for his work with productions like Hairspray and films like Independence Day.[47] He also wrote the book for the musical La Cage aux Folles and has won four Tony Awards for Best Actor in a Play, Best Play, Best Book of a Musical, and Best Actor in a Musical.[47]

Plays & Musicals with LGBT+ characters or themes

editMusicals

edit- Bare: A Pop Opera by Jon Hartmere and Damon Intrabartolo

- Bare: The Musical by Jon Hartmere, Damon Intrabartolo, and Lynne Shankel

- Cabaret by Fred Ebb, John Kander, and Joe Masteroff

- La Cage Aux Folles by Harvey Fierstein and Jerry Herman

- The Color Purple by Stephen Bray, Marsha Norman, Brenda Russell, and Allee Willis

- Falsettos by William Finn and James Lapine

- Fun Home by Lisa Kron and Jeanine Tesori

- Hedwig and the Angry Inch by John Cameron Mitchell and Stephen Trask

- Kinky Boots by Harvey Fierstein and Cyndi Lauper

- Kiss of the Spider Woman by Fred Ebb, John Kander, and Terrence McNally

- Rent by Jonathan Larson

- Spring Awakening by Steven Sater and Duncan Sheik

- A Strange Loop by Michael R. Jackson

- The View UpStairs by Max Vernon

Plays

edit- Angels in America by Tony Kushner

- Bent by Martin Sherman

- The Boys in the Band by Mart Crowley

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams

- Corpus Christi by Terrence McNally

- The Laramie Project by Moisés Kaufman and members of the Tectonic Theater Project

- M. Butterfly by David Henry Hwang

- The Normal Heart by Larry Kramer

- Stop Kiss by Diana Son

- Torch Song Trilogy by Harvey Fierstein

- The Prince by Abigail Thorn

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Wang, Wencong (June 2014). "Lesbianism and Lesbian Theatre". Comparative Literature: East & West. 21 (1): 113–123. doi:10.1080/25723618.2014.12015466. ISSN 2572-3618.

- ^ Flynn, James. "Love and Soldiers". National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Hemingway, Colette. "Theater in Ancient Greece | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Aristophanes. Knights. 1255

- ^ Thesmophoriazusae lines 383–530

- ^ Wittenberg, Hayley Rhodes (2023-06-02). "He Whom I Loved as Dearly as My Own Life: An Analysis of the Relationship Between Achilles and Patroclus". Scientia et Humanitas. 13: 47–57. ISSN 2470-8178.

- ^ a b "18th century Queer Cultures #1: the Macaroni and his ancestors • V&A Blog". V&A Blog. 2015-03-04. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Women Performers in Shakespeare's Time | Folger Shakespeare Library". folger.edu. 2019-11-12. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "When men were men (and women, too)". Harvard Gazette. 2003-07-17. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g Green, Jesse (2018-02-26). "A Brief History of Gay Theater, in Three Acts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Caffe Cino: Birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b c "LGBTQ+ Playwrights, Plays and all that jazz | Library". 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b "La Cage aux Folles | The Shows". Broadway: The American Musical. PBS. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Grode, Eric (2021-02-25). "The Birth of 'Rent,' Its Creator's Death and the 25 Years Since". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Russo, Gillian (2022-03-03). "Guide to The Book of Mormon on Broadway". New York Theatre Guide. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "LGBTQ Issues & the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (2010-03-03). "'The Band' Helped Writers Find Their Beat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ Grunfeld, Aaron (June 21, 2016). "15 Regional Companies Leading the Charge in Gay Theatre". Playbill. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Lord chamberlain | Definition, Duties, & Censorship | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b c d e f Tu, KaiChieh (2016-09-04). "Taiwanese Experimental and Queer Theater: Always Political, Always Queer". The Theatre Times. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Ross, Alex (August 1, 2011). "How Oscar Wilde Painted Over "Dorian Gray"". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Controversy and Resilience in the Theater". Georgia Exhibits. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Kozlov, Vladmir (April 26, 2016). "Bomb Threat Disrupts Moscow Screening of Transgender Film". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Chernov, Sergey (November 27, 2013). "Film Festival Faces Bomb Threats and Cancellations". The Moscow Times. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Russia: Expanded 'Gay Propaganda' Ban Progresses Toward Law". Human Rights Watch. November 25, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "The Greatest LGBTQ+ Musicals". Matinee. January 6, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Wilkie, Tiffany (June 21, 2021). "35 Plays to Pick Up for LGBTQ+ Pride Month". Performer Stuff. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Lozano, Carlos (June 23, 2018). "Bomb threat leads to cancellation of concert by Gay Men's Chorus at Alex Theatre". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Bomb threat forces evacuation of Gay Men's Chorus performance". Pasadena Weekly. June 28, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Migdon, Brooke (July 18, 2023). "House Republicans eliminate funding to LGBTQ community centers after tense hearing". The Hill. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Natanson, Hannah (May 2, 2023). "The culture war's latest casualty: The high school musical". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Butler, Isaac; Kois, Dan (February 13, 2018). "Angels in North Carolina: How one Southern theater won a culture battle but lost the culture wars". Slate. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "#OUTLAWED "THE LOVE THAT DARE NOT SPEAK ITS NAME"". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Time, Current (November 21, 2022). "Children's Theater Canceled In Russia Following Promised Investigation Of Alleged LGBTQ 'Propaganda'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "In Russia, a children's play was canceled due to an alleged violation of an anti-LGBTI+ law". Sloboden Pečat. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Karasz, Palko (June 22, 2018). "'Billy Elliot' Musical Branded Gay Propaganda in Hungary; Cancellations Follow". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ McPhee, Ryan (June 25, 2018). "Hungarian Production of Billy Elliot Cancels Portion of Run After Conservative Backlash". Playbill. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "Openly Gay Actors". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "LGBT Actors". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ "Notable LGBTQ Playwrights". QueerBio.com. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b c "Oscar Wilde | Biography, Books, & Facts". Britannica. Retrieved 2024-02-01.

- ^ a b c "Tennessee Williams | Plays, Education, Biography, & Facts". Britannica. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b "Edward Albee | Pulitzer Prize-Winning Playwright". Britannica. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b "Tony Kushner | Writer, Actor, Producer". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b "Mart Crowley | Producer, Script and Continuity Department, Writer". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b "John Waters | Actor, Writer, Director". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ a b c "Harvey Fierstein | Actor, Writer, Soundtrack". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-02-02.