Revanchism (French: revanchisme, from revanche, "revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse the territorial losses which are incurred by a country, frequently after a war or after a social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s France in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War among nationalists who wanted to avenge the French defeat and reclaim the lost territories of Alsace-Lorraine.[1]

Revanchism draws its strength from patriotic and retributionist thought and is often motivated by economic or geopolitical factors. Extreme revanchist ideologues often represent a hawkish stance, suggesting that their desired objectives can be achieved through the positive outcome of another war. It is linked with irredentism, the conception that a part of the cultural and ethnic nation remains "unredeemed" outside the borders of its appropriate nation-state.[2]

Revanchist politics often rely on the identification of a nation with a nation state, mobilizing sentiments of ethnic nationalism to claim territories outside of where members of the ethnic group currently live. Such claims are often presented as being based on ancient or even autochthonous occupation of a territory since "time immemorial".

History

editFrance

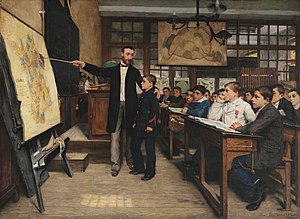

editThe instance of revanchism that gave these groundswells of opinion their modern name came in the 1870s. French revanchism was a deep sense of bitterness, hatred and demand for revenge against Germany, especially because of the loss of Alsace and Lorraine following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.[3][4] Paintings that emphasized the humiliation of the defeat came in high demand, such as those by Alphonse-Marie-Adolphe de Neuville.[1]

Georges Clemenceau, of the Radical Republicans, opposed participation in the scramble for Africa and other adventures that would divert the Republic from objectives related to the "blue line of the Vosges" in Alsace-Lorraine. After the governments of Jules Ferry had pursued a number of colonies in the early 1880s, Clemenceau lent his support to Georges Ernest Boulanger, a popular figure, nicknamed Général Revanche, who it was felt might overthrow the Republic in 1889. This ultranationalist tradition influenced French politics up to 1921 and was one of the major reasons France went to great pains to woo the Russian Empire, resulting in the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894 and, after more accords, the Triple Entente of the three great Allied powers of World War I: France, Great Britain, and Russia.[5]

French revanchism influenced the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 following the end of World War I, which restored Alsace-Lorraine to France and extracted reparations from the defeated Germany. The conference was not only opened on the anniversary of the proclamation of the German Empire; the treaty also had to be signed by the new German government in the same room, the Hall of Mirrors.

Germany

editA German revanchist movement developed in response to the losses of World War I. Pan-Germanists within the Weimar Republic called for the reclamation of the property of a German state due to pre-war borders or because of the territory's historical relation to Germanic peoples. The movement called for the reincorporation of Alsace-Lorraine, the Polish Corridor and the Sudetenland (see Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia—parts of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary until its dismemberment after World War I). Those claims, supported by Adolf Hitler, led to World War II, with the invasion of Poland. This irredentism had also been characteristic of the Völkisch movement in general and of the Pan-German League (Alldeutscher Verband). The Verband wanted to uphold German "racial hygiene" and were against breeding with, in their eyes, inferior races like the Jews and Slavs.[6]

Greece

editGreek revanchism refers to the political sentiment or movement advocating for the restoration or reclaiming of territories historically or culturally once associated with Greece, but currently under the control of other states. Stemming from unresolved territorial disputes, Greek revanchism often manifests in nationalist rhetoric, diplomatic tensions, and occasional military confrontations. Historical grievances, such as the population exchanges between Greece and Turkey following World War I, also fuel revanchist sentiments.[7] While Greek revanchism has influenced foreign policy decisions and public discourse, it remains a contentious and complex issue in the broader context of regional geopolitics and international relations.[8]

Poland

editIn the 1920s and 1930s, Poland was trying to reclaim ethnic Polish lands that had been seized by German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires:

Poland counted herself among the revisionist powers, with dreams of a southward advance, even a Polish presence on the Black Sea. The victim of the revisionist claims of others, she did not see the Versailles frontiers as fixed either. In 1938 when the Czech state was dismembered at the Munich conference, Poland issued an ultimatum of her own to Prague, demanding the cession of the Teschen region; the Czech government was powerless to resist.[9]

Sweden

editSweden lost Finland to Russia at the conclusion of the Finnish War (1808–09), ending nearly 600 years of Swedish rule. For most of the rest of the 1800s there was talk, but few practical plans and little political will, of reclaiming Finland from Russia. Since Sweden was never able to challenge Russia's military might on its own, no attempts were made.

During the Crimean War in 1853 to 1856, the Allied nations initiated talks with Sweden to allow troop and fleet movements through Swedish ports to be used against Russia. In return, the Allies would help Sweden reclaim Finland with the help of an expeditionary force. In the end, the plans fell through and Sweden never became involved in the fighting.

Hungary

editThe idea of Greater Hungary is associated with Hungarian revisionist aims at least to regain control over Hungarian-populated areas in Hungary's neighbouring countries. The outcome of the Treaty of Trianon of 1920 is to this day remembered in Hungary as the Trianon trauma.[10] According to a study, two-thirds of Hungarians agreed in 2020 that parts of neighbouring countries should belong to them.[11]

Mexico

editSome Mexican nationalists consider the Southwestern United States to be Mexican territory that must be returned.[12][13] The territory belonged to Mexico until 1836 when Texas established itself as its own nation. Texas citizens then voted to join the United States in the Texas annexation (1845) leading to the 1846-48 Mexican–American War and, as a consequence of the war, the Mexican Cession of further territory that now constitutes much of the western US.

In 1865, as the American Civil War ended, Maximilian "was actively recruiting Confederate refugees to colonize northern Mexico and bring their slaves with them. Grant foresaw that Maximilian was creating a base from which diehard rebels would carry on a revanchist war against the United States and create an obstacle protecting Maximilian's empire against invasion by U.S. forces".[14]

Russia

editThe annexation of the Crimean peninsula by the Russian Federation in April 2014, together with accusations by Western and Ukrainian leaders that Russia is supporting separatist actions by ethnic Russians in the secessionist Donbas region, has been cited by a number of prominent media outlets in the West as evidence of a revanchist policy on the part of the Kremlin and Russian President Vladimir Putin.[15][16] The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has the same origins.[17][18]

Some Russian nationalists consider Alaska to be Russian territory that must be returned.[19] Alaska was legally sold to the United States by Russia in 1867.

Argentina

editArgentina considers the British-controlled Falkland Islands to be part of the Tierra del Fuego Province. In 1994, Argentina's claim to the territories was added to its constitution.[20]

During the interwar period, the Argentine fascist ideology Nacionalista and organizations such as the Alliance of Nationalist Youth openly supported plans to annex Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile and some southern and eastern parts of Bolivia, which they claimed belonged to Argentina via past territories of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

Spain

editSpain ceded Gibraltar to Britain under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713. Spain's claim to Gibraltar became government policy under the regime of the dictator Francisco Franco and has remained in place under successive governments following the Spanish transition to democracy.[21]

Iraq

editSaddam Hussein's government sought to annex several territories. In the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), Saddam claimed that Iraq had the right to hold sovereignty to the east bank of the Shatt al-Arab river held by Iran.[22]

The Iraqi government, echoing claims made by Iraqi nationalists for years, justified the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 by claiming that Kuwait had always been an integral part of Iraq and only became an independent nation due to the interference of the British government.[23]

It has been suspected that Saddam Hussein intended to invade and annex a portion of Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province on the justification that the Saudi region of Al-Hasa had been part of the Ottoman province of Basra that the British had helped Saudi Arabia conquer in 1913.[24]

Turkey

editThe 21st century has seen a domestic trend in Turkish politics, where the revival of Ottoman traditions and culture has been accompanied by the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP, founded in 2001) which came to power in 2002, along with claims to territory once held by the Ottoman Empire. The use of the ideology by Justice and Development Party has mainly supported a greater influence of Ottoman culture in domestic social policy which has caused issues with the secular and republican credentials of modern Turkey.[25][26] The AKP have used slogans such as Osmanlı torunu ("descendant of the Ottomans") to refer to their supporters and also their former leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (who was elected President in 2014) during their election campaigns.[27] These domestic ideals have also seen a revival of neo-Ottomanism in the AKP's foreign policy. Besides acting as a clear distinction between them and ardent supporters of secularism, the social Ottomanism advocated by the AKP has served as a basis for their efforts to transform Turkey's existing parliamentary system into a presidential system, favouring a strong centralised leadership similar to that of the Ottoman era. Critics have thus accused Erdoğan of acting like an "Ottoman sultan".[28][29][30]

The rise in Ottomanism has also been accompanied by claims to territories held by Armenia, with prominent examples including in 2015, a crowd of Turkish youth rallying in Armenian populated districts of Istanbul chanted "We must turn these districts into Armenian and Kurdish cemeteries."[31] In September 2015, a 'Welcome' sign was installed in Iğdır and written in four languages, Turkish, Kurdish, English, and Armenian. The Armenian portion of the sign was protested by the "Fight against Armenian groundless allegations” alliance (ASIMDER) who demanded its removal.[32] In October 2015, the Armenian writing on the 'Welcome' sign was heavily vandalized.[33] The Armenian portion of the sign was ultimately removed in June 2016.[34] The Mayor of Igdir also claimed that the existence of the Armenian state was a "historical mistake", and that Armenia is actually Turkish territory, illegally occupied by Armenians, waiting to be re-integrated into Turkey.[34]

Ukraine

editOn 24 March 2021, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed the Decree No. 117/2021 approving the "strategy of de-occupation and reintegration of the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol", complementing the activities of the Crimean Platform.[35] On 10 May 2022, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said that "In the first months" of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine "the victory for us looked like withdrawal of Russian forces to the positions they occupied before February 24 and payment for inflicted damage. Now if we are strong enough on the military front and we win the battle for Donbas, which will be crucial for the following dynamics of the war, of course the victory for us in this war will be the liberation of the rest of our territories", including Donbas and Crimea.[36]

China

editThe People's Republic of China (PRC) has used historical claims in the South China Sea (SCS) as justification for island building activities and revised territorial claims. The "nine-dash line" map extends the area that the PRC identifies as within its sovereign territory disregarding several international laws of the sea. In addition to civil and military confrontations in the SCS, other territorial disputes have affected Japan,[37] India,[38] and Taiwan. See also Chinese irredentism.

See also

edit- Expansionism

- Franco-Prussian War (1870)

- French–German enmity

- French Third Republic (1870–1940)

- Former eastern territories of Germany

- Greater Israel

- Greater Palestine

- Historical revisionism

- Independence movement in Puerto Rico

- Irredentism

- Irish republicanism

- Legal status of Hawaii

- Legal status of Texas

- Lists of active separatist movements

- Karelian question

- Mutilated victory

- Ogaden War

- Polish–Czechoslovak border conflicts

- Polish–Lithuanian War

- Polish–Ukrainian War

- Quebec sovereignty movement

- Reconquista (Mexico)

- Recovered Territories

- Rump state (a geopolitical state of existence that revanchism may create, seek to correct, or both)

- Status quo ante bellum

- Uti possidetis

References

edit- ^ a b Jay, Robert (1984). "Alphonse de Neuville's 'The Spy' and the Legacy of the Franco-Prussian War". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 19–20: 151–162. doi:10.2307/1512817. JSTOR 1512817. S2CID 193058659.

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013), ch. 6.

- ^ Karine Varley, "The Taboos of Defeat: Unmentionable Memories of the Franco-Prussian War in France, 1870–1914." in Jenny Macleod, ed., Defeat and Memory: Cultural Histories of Military Defeat in the Modern Era (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) pp. 62–80.

- ^ Karine Varley, Under the Shadow of Defeat: The War of 1870–71 in French Memory (2008)

- ^ See W. Schivelbusch, The Culture of Defeat, p. 106 (Henry Holt and Co. 2001)

- ^ Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. Richard S. Levy, 528–529, ABC-CLIO 2005

- ^ Ploumidis, Spyridon G. (2020). "Nationalism and authoritarianism in interwar Greece (1922–1940)". Conservatives and Right Radicals in Interwar Europe. Routledge. pp. 215–236. doi:10.4324/9780429275272-10. ISBN 978-0-429-27527-2.

- ^ Dedja, Stiljan (22 January 2024). "Greece continues to hinder Albania on its European path". Sot News. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Overy, Richard; Wheatcroft, Andrew (1999). The Road to War. Penguin. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-14-028530-7.

- ^ Kulish, Nicholas (7 April 2008). "Kosovo's Actions Hearten a Hungarian Enclave". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ "NATO Seen Favorably Across Member States". pewresearch.org. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Fuentes, Carlos (2003). "Unidad y diversidad del español, lengua de encuentros" [Unity and Diversity of the Spanish Language, Language of Encounters]. Congresos de la Lengua (in Spanish). Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Krauze, Enrique (April 6, 2017). "Will Mexico Get Half of Its Territory Back?". The New York Times.

- ^ Doyle, Don H. (2024). The Age of Reconstuction: How Lincoln's New Birth of Freedom Remade the World. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, p. 74.

- ^ Romano, Carlin (21 July 2014). "Revanchism and Its Costs". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 27 Jul 2014.

- ^ Niblett, Robin (12 April 2014). "The West must not blame itself for Putin's revanchism". CNN.com. Retrieved 27 Jul 2014.

- ^ "Putin's revanchist excuses for going to war". The Strategist. 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Hailing Peter the Great, Putin draws parallel with mission to 'return' Russian lands". Reuters. 9 June 2022.

- ^ Farand, Chloe (31 March 2017). "Russian nationalists want Alaska back - 150 years after it was sold to the US". Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "Constitución Nacional". Argentine Senate (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2004.

La Nación Argentina ratifica su legítima e imprescriptible soberanía sobre las Islas Malvinas, Georgias del Sur y Sandwich del Sur y los espacios marítimos e insulares correspondientes, por ser parte integrante del territorio nacional.

- ^ "Spain won't dare invade Gibraltar – They'd lose more than a war". The Jerusalem Post. 13 April 2017.

- ^ Goldstein, Erik (2005). Wars and Peace Treaties: 1816 to 1991. Taylor & Francis. p. 133. ISBN 9781134899128.

- ^ R. Stephen Humphreys, Between Memory and Desire: The Middle East in a Troubled Age, University of California Press, 1999, p. 105.

- ^ Amatzia Baram, Barry Rubin. Iraq's Road To War. New York, New York, USA: St. Martin's Press, 1993. Pp. 127.

- ^ "İstanbul Barosu'ndan AKP'li vekile çok sert tepki". www.cumhuriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "AKP'li vekil: Osmanlı'nın 90 yıllık reklam arası sona erdi". www.cumhuriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "İslami Analiz". www.islamianaliz.com. Archived from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "AKP'nin Osmanlı sevdası ve... - Barış Yarkadaş". Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "Yeniden Osmanlı hayalinin peşinden koşan AKP, felaketi yakaladı!." www.sozcu.com.tr (in Turkish). 15 May 2013. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "Kılıçdaroğlu: AKP çökmüş Osmanlıcılığı ambalajlıyor". T24 (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- ^ "Armenian-Populated Districts of Istanbul Attacked". Asbarez. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Kurdish Mayor of Igdir Installs 'Welcome' Sign in Armenian". Asbarez. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "İlçe girişindeki Ermenice yazıyı tahrip ettiler" (in Turkish). CNN Turk. 12 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Armenian Signboards Removed in Igdir". Asbarez. 21 June 2016.

- ^ "Zelensky enacts strategy for de-occupation and reintegration of Crimea". Ukrinform. Government of Ukraine. 24 March 2021.

Decree No. 117/2021 of March 24 on enactment of the relevant decision of the National Security and Defense Council was published on the website of the Head of State.

- ^ "Ukraine has upgraded its war aims as confidence grows, says foreign minister". Financial Times. 10 May 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10.

- ^ Lee, John (2013-03-02). "Beware a revanchist China". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- ^ "Taming the Revanchist Dragon". www.delhipolicygroup.org. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

Bibliography

edit- Akçam, Taner (2007), A Shameful Act, London: Macmillan

- Akmeșe, Handan Nezir (2005), The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to World War I, London: IB Tauris

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (26 June 2018), Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide, Princeton University Press (published 2018), ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7