The Princess Theatre was a joint venture between the Shubert Brothers, producer Ray Comstock, theatrical agent Elisabeth Marbury and actor-director Holbrook Blinn. Built on a narrow slice of land located at 104–106 West 39th Street, just off Sixth Avenue in New York City, and seating just 299 people, it was one of the smallest Broadway theatres when it opened in early 1913. The architect was William A. Swasey, who designed the Winter Garden Theatre two years earlier.[1][2]

| |

| |

| Address | 104–106 West 39th Street |

|---|---|

| Location | New York City |

| Owner | The Shubert Organization |

| Type | Broadway |

| Capacity | 299 |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1913 |

| Demolished | 1955 |

| Architect | William A. Swasey |

Though small, the theatre had a profound effect on the development of American musical theatre. After producing a series of plays, the theatre hosted a famous series of sophisticated musicals by the team of Jerome Kern, Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, between 1915 and 1918 that were believable, humorous and musically innovative, and integrated their songs with their stories. These were considered an artistic step forward for American musical theatre, inspiring the next generation of writers and composers. Afterwards, the theatre hosted more plays and later served as a movie theatre and a recreation center. It was torn down in 1955.[2][3]

Theatre building

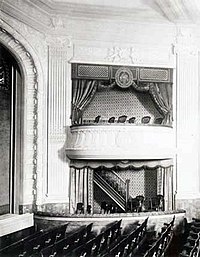

editThough fairly drab on the outside, looking like a six-story office building, except for its marquees and gaudy electric sign over the main entrance, the Princess was elegant inside. A blend of Georgian and French Renaissance styles, the auditorium contained fourteen rows of seats and twelve boxes off the proscenium arch and was hailed for its excellent acoustics and sight-lines. The decor included neoclassical inspired plasterwork and antique French tapestries hung from the side walls.

1910s

editOriginally planned as a venue for short dramatic plays, the early shows at the Princess failed to attract an audience.[4] Even so, some of these plays found success elsewhere. For example, Hobson's Choice (1915) played well in London the following year and became a success on film. Theatre agent Elisabeth Marbury was tasked with booking the theatre to improve its fortunes and approached young Jerome Kern, who suggested a collaboration with Guy Bolton, to write a series of musicals specifically tailored to its smaller setting, with an intimate style and modest budgets.[3] She and Comstock asked for meaningful, modern, sophisticated pieces that would provide an alternative to the star-studded revues and extravaganzas of Ziegfeld and others or the thinly-plotted, slapdash, gaudy Edwardian musical comedies and operetta imports from Europe.[4][5]

Kern and Bolton's first "Princess Theatre musical" was Nobody Home (1915), an adaptation of a 1905 London show by Paul Rubens called Mr. Popple (of Ippleton). The show was notable for Bolton's realistic take on courtship complications and Kern's song "The Magic Melody", the first Broadway showtune with a basic jazz progression. Their second show, with Philip Bartholomae and lyrics by Schuyler Green, was an original musical called Very Good Eddie (1915). The little show ran for 341 performances on a modest budget[6] then toured into the 1918–19 season.[7]

British humorist and lyricist/playwright P. G. Wodehouse had supplied some lyrics for Very Good Eddie but now joined the team and collaborated with Kern and Bolton at the theatre for Oh, Boy! (1917), which ran for 463 performances and was one of the first American musicals to have a successful London run.[8] According to Bloom and Vlastnik, Oh, Boy! represents "the transition from the haphazard musicals of the past to the newer, more methodical modern musical comedy ... the libretto is remarkably pun-free and the plot is natural and unforced. Charm was uppermost in the creators' minds ... the audience could relax, have a few laughs, feel slightly superior to the silly undertakings on stage, and smile along with the simple, melodic, lyrically witty but undemanding songs".[9] Next, the team wrote Oh, Lady! Lady!! (1918). Two other shows, Leave It to Jane and Have a Heart, were written by the three in 1917 for the Princess but presented elsewhere.[5] They also wrote several musicals for other theatres, such as Miss 1917.

The Princess Theatre shows featured modern American settings and simple scene changes (one set for each act) to more aptly suit the small theatre, eschewing operetta traditions of foreign locales and elaborate scenery.[4] According to historian Gerald Bordman, writing in The Musical Times,

"These shows built and polished the mold from which almost all later major musical comedies evolved. As they all dealt with the smart set they were stylishly mounted – sometimes with settings by the fashionable Elsie de Wolfe. ... The characters and situations were, within the limitations of musical comedy license, believable and the humor came from the situations or the nature of the characters. Kern's exquisitely flowing melodies were employed to further the action or develop characterization. The integration of song and story is periodically announced as a breakthrough in ... musical theater. Great opera has always done this, and it is easy to demonstrate such integration in Gilbert and Sullivan or the French opera bouffe. However, early musical comedy was often guilty of inserting songs in a hit-or-miss fashion. The Princess Theatre musicals brought about a change in approach. [Lyricist] P. G. Wodehouse, the most observant, literate, and witty lyricist of his day, and the team of Bolton, Wodehouse, and Kern had an influence which can be felt to this day.[5]

The collaboration among Kern, Bolton and Wodehouse was much praised. An anonymous admirer (believed by some critics to be the young Lorenz Hart),[10] wrote a verse in praise of the trio[11] that begins:

- This is the trio of musical fame,

- Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern.

- Better than anyone else you can name

- Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern.[10]

In February 1918, Dorothy Parker wrote in Vanity Fair:

Well, Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern have done it again. Every time these three gather together, the Princess Theatre is sold out for months in advance. You can get a seat for Oh, Lady! Lady!! somewhere around the middle of August for just about the price of one on the stock exchange. If you ask me, I will look you fearlessly in the eye and tell you in low, throbbing tones that it has it over any other musical comedy in town. But then Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern are my favorite indoor sport. I like the way they go about a musical comedy. ... I like the way the action slides casually into the songs. ... I like the deft rhyming of the song that is always sung in the last act by two comedians and a comedienne. And oh, how I do like Jerome Kern's music. And all these things are even more so in Oh, Lady! Lady!! than they were in Oh, Boy! [12]

Oh, Lady! Lady!! was the last successful "Princess Theatre show". Kern and Wodehouse disagreed over money, and the composer decided to move on to other projects.[13] Kern's importance to the partnership was illustrated by the fate of the last musical of the series, Oh, My Dear! (1918), to which he did not contribute. It was composed by Louis Hirsch, and ran for 189 performances: "Despite a respectable run, everyone realized there was little point in continuing the series without Kern."[6] Musicals by other teams followed at the theatre, but without especial success.

1920s

editIn 1922, drama returned to the Princess for another seven years, but success did not. The theatre's most popular plays in this decade were Diff'rent by Eugene O'Neill (1921) and a production of Six Characters in Search of an Author (1922). After a brief stint as the Lucille La Verne Theatre in 1928, the Shuberts sold the theatre. In 1929, the New York Theatre Assembly took over the Princess, and renamed it the Assembly Theatre. However, within half a year, the theatre was closed, and remained unused until 1933, when it reopened as the Reo Theatre, and was, like so many other former legitimate houses, now being used as a movie theatre. A year later, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) acquired the theatre, and used it as a recreation center for neighborhood workers.[2]

1930s to 1950s

editHowever, in 1937, legitimate theatre returned to the theatre, now called the Labor Stage, with a surprise hit. The revue Pins and Needles became the longest-running Broadway show of the day, running for 1,108 performances. When the show moved to the Windsor Theatre, the ILGWU reclaimed the Labor Stage briefly as its recreation hall.[4]

On October 5, 1947, Elia Kazan, Cheryl Crawford, Robert Lewis and Anna Sokolow met in a rehearsal space at the Labor Stage to form what would become the Actors Studio.[14] The same year, movies returned to the theatre, now renamed the Cinema Dante, screening foreign features. A year later, it got another name change, The Little Met, and in 1952, yet one final name, the Cine Verdi.[2] By the mid-50s, the old Princess was on the outskirts of the theatre district, which had migrated north, and in 1955, the little theatre was torn down, replaced by an office building.

Selected productions

edit- Fear (1913)

- The Critic (1915)

- Hobson's Choice (1915)

- Nobody Home (1915)

- Very Good Eddie (1915)

- Oh, Boy! (musical) (1917)

- Oh, Lady! Lady!! (1918)

- Oh, My Dear! (1918)

- Diff'rent (1921)

- Six Characters in Search of an Author (1922)

- Mister Malatesta (1923)

- Pins and Needles (1937)

Notes

edit- ^ "12 Shows to Open Here This Month", The New York Times, October 3, 1942

- ^ a b c d Kenrick, John. "Demolished Broadway Theatres: Princess", Musicals101.com, accessed November 12, 2015

- ^ a b Mroczka, Paul. "Broadway History: The Princess Musicals, Bigger Was NOT Better", BroadwayScene.com, July 8, 2013, accessed November 12, 2015

- ^ a b c d Bloom and Vlastnik, pp. 230–31

- ^ a b c Bordman, Gerald. "Jerome David Kern: Innovator/Traditionalist", The Musical Quarterly, 1985, Vol. 71, No. 4, pp. 468–73

- ^ a b Kenrick, John. "History of The Musical Stage 1910–1919: Part I", Musicals 101.com: The Cyber Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre, TV and Film, accessed November 12, 2015

- ^ Slonimsky, Nicholas and Laura Kuhn (ed). Kern, Jerome (David)". Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, Volume 3 (Schirmer Reference, New York, 2001), accessed May 10, 2010 (requires subscription)

- ^ Oh, Boy! was staged in London as Oh, Joy! in 1919, when it ran for 167 performances: see Jasen, p. 279

- ^ Bloom and Vlastnik, p. 277

- ^ a b Steyn, Mark. "Musical debt to a very good Guy", The Times, November 28, 1984, p 12

- ^ The poem is patterned after "Baseball's Sad Lexicon", about the Chicago Cubs' infield. See Frankos, Laura. "Musical of the Month: Oh, Boy!", New York Public Library, August 27, 2012, accessed September 11, 2015

- ^ quoted in Green, p. 110

- ^ Suskin, Steven (2000). Show Tunes: The Songs, Shows, and Careers of Broadway's Major Composers. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-512599-3.

- ^ Carnicke, Sharon Marie. Stanislavsky in Focus, Routledge (1998), p. 47 ISBN 90-5755-070-9

References

edit- Bloom, Ken and Vlastnik, Frank. Broadway Musicals: The 101 Greatest Shows of all Time. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, New York, 2004. ISBN 1-57912-390-2

- Green, Benny. P. G. Wodehouse – A Literary Biography, Pavilion Books, London, 1981. ISBN 0-907516-04-1

- Jasen, David. P. G. Wodehouse – Portrait of a Master, Garnstone Press, London, 1974. ISBN 0-85511-190-9

External links

edit- Media related to Princess Theatre (New York City, 1913-1955) at Wikimedia Commons

- Princess Theatre at the Internet Broadway Database