Lake City is a city in and the county seat of Columbia County, Florida, United States.[4] As of the 2020 census, the city's population was 12,329, up from 12,046 at the 2010 census. It is the principal city of the Lake City Micropolitan Statistical Area, composed of Columbia County, as well as a principal city of the Gainesville—Lake City, Florida Combined Statistical Area. Lake City is 60 miles west of Jacksonville.

Lake City, Florida | |

|---|---|

| City of Lake City | |

Top, left to right: Downtown Lake City, Columbia County Courthouse, Lake Isabella, Lake Montgomery, Lake DeSoto, 1912 Columbia County Bank building, Hotel Blanche, T. G. Henderson House | |

| Nickname: The Gateway to Florida | |

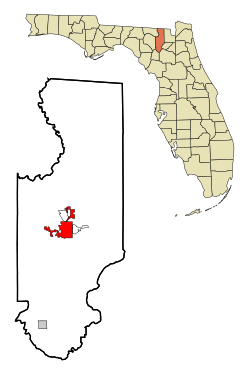

Location in Columbia County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 30°11′N 82°38′W / 30.183°N 82.633°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Columbia |

| Settled | 1821 |

| Incorporated | 1859 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Noah Walker |

| • City Manager | Don Rosenthal |

| Area | |

• City | 12.25 sq mi (31.73 km2) |

| • Land | 11.85 sq mi (30.69 km2) |

| • Water | 0.40 sq mi (1.04 km2) 3.20% |

| Elevation | 197 ft (60 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 12,329 |

| • Density | 1,040.60/sq mi (401.79/km2) |

| • Metro | 67,531 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 32024-32025, 32055-32056 |

| Area code | 386 |

| FIPS code | 12-37775[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0305917[2] |

| Website | www |

Lake City began as the town of Alligator[5] in 1821 near the Seminole settlement known as Alligator Village. Alligator became the seat of Columbia County in 1832 when it was formed from Duval and Alachua counties. In 1858, Alligator was incorporated and renamed Lake City. The Battle of Olustee, the largest American Civil War battle in Florida, took place near Lake City in 1864. In 1884, the Florida Agricultural College was established in Lake City as a land grant college; it was relocated to Gainesville in 1905 to form part of the University of Florida. The city's sesquicentennial was held in 2009.[6]

Lake City is known as "The Gateway to Florida" because it is adjacent to the intersection of Interstate 75 and Interstate 10. The city is the site of Lake City Gateway Airport, formerly known as NAS Lake City. Florida Gateway College is located in Lake City.

History

editTimucua and Spanish Florida

editIn 1539, Hernando de Soto and his Spanish expedition arrived in Tampa Bay. The de Soto expedition proceeded north from Tampa Bay looking for gold. His expedition met a large Native American group called the northern Utina, possibly near present-day Lake City, who were part of the western Timucua people. Some northern Utina were led by powerful chiefs. In the 17th century Spanish missionaries established missions in this area, west of the site of present-day Lake City. Called Santa Cruz de Tarihica, it was used by the Spanish to develop agriculture and bring Native Americans within their sphere.[7]

Alligator

editIn the 18th century, a Seminole community called Alligator Village (Alapata Telophka) occupied this area. Historians do not know when it was established, but its existence was documented by the U.S. Army in 1821. A February 1821 report by Captain John H. Bell mentions that the mico (chief) of Alligator Village had recently died and missed a gathering of chiefs. The most famous resident of Alligator Village was Alligator Warrior (Halpatter Tustenuggee), also known as Chief Alligator. He was the grandson of Micanopy (King) Payne (Mekk-Onvpv Pin) and led Seminole warriors in the Second Seminole War (1835–1842) to resist their people's relocation to the Arkansas Territory (now known as Oklahoma).

After Florida became a territory of the United States in 1821, pioneer and immigrant settlers from the United States formed their own settlement adjacent to Alligator Village and called it Alligator.[8] Following the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the residents of Alligator village relocated to the banks of Peace Creek in the newly established Seminole reservation, leaving Alligator Town on its own. When Columbia County was formed in 1832 from Duval and Alachua counties, Alligator Town was designated as the seat of the county government.

During the Seminole Wars, several forts were established in the area, including Fort White on the Santa Fe River, and Fort Alligator, also called Fort Lancaster, in present-day downtown Lake City. By 1845, the last of the Seminole left the area of present-day Lake City or were forcibly removed by the US Army.[9] In 1847, Company C of the Florida Volunteers, which was composed of Lake City members, served in the Mexican–American War.

In November 1858, a railroad was completed connecting Jacksonville to Alligator, which opened the town to more commerce and passenger traffic. Alligator Town was incorporated and its name changed to Lake City in 1859; M. Whit Smith was elected as the town's first mayor.[10] According to an urban legend, the name was changed because the mayor's wife Martha Jane, who had recently moved to the town, refused to hang her lace curtains in a town named Alligator.[11]

Civil War

editDuring the American Civil War the railroad between Lake City and Jacksonville was used to send beef and salt to Confederate soldiers. During the summer of 1862, the 8th Florida Infantry Regiment was mustered in at Lake City. The unit was soon deployed to Virginia and fought as part of the Army of Northern Virginia.[12]

In February 1864, Union troops under Truman Seymour advanced west from Jacksonville. His objective was to disrupt Confederate supplies, and obtain African-American recruits and supplies.[13] Confederate General Joseph Finnegan assembled troops and called for reinforcements from P. G. T. Beauregard in response to the Union threat. On February 11, 1864, Finnegan's troops defeated a Union cavalry raid in Lake City.[13] After the Union cavalry was repulsed, Finnegan moved his forces to Olustee Station about ten miles east of Lake City. The Confederate presence at Olustee Station was reinforced to prepare for the Union troops coming from Jacksonville.

Union forces engaged the Confederates at the Battle of Olustee on February 20, 1864, near the Olustee Station. It was the only major battle in Florida during the war. Union casualties were 1,861 men killed, wounded or missing; Confederate casualties were 946 killed, wounded or missing. The Confederate dead were buried in Lake City.[14] In 1928 a memorial for the Battle of Olustee was established in downtown Lake City.

The Civil War badly damaged Florida's railroads, including the Florida, Atlantic and Gulf Central Railroad. The railroad was rebuilt by carpetbagger George William Swepson and was renamed the Florida Central Railroad in 1868. In 1869, the Pensacola and Georgia Railroad was merged with a railroad from Jacksonville to Lake City to form the Jacksonville, Pensacola and Mobile Railroad. In 1874, a fire destroyed most of the wooden buildings in Lake City.[15]

Modern Lake City

editIn 1874, Lake City's first newspaper was published, called the Lake City Reporter. In 1876, the Bigelow Building was completed; it later was adapted for use as the City Hall. In 1891, Lake City became the first city in Florida to have electric lights from a local power and light company.

By the early 20th century, Lake City had become an important railroad junction, served by the Seaboard Air Line, Atlantic Coast Line, Georgia Southern and Florida Railroad.[16] Hotel Blanche was built in 1902 as an attraction for expected tourists. The hotel was Lake City and Columbia County's major hotel and central business center from 1902 to 1955.

The population of Lake City in 1900 was 4,013; in 1905 was 6,509; and 1910 was 5,032.[5]

Florida Agricultural College was established in 1884 as part of the Morrill Land Grant Act; in 1904 it became a full university with twenty-five instructors. In 1905 the Florida Agricultural College was moved to Gainesville, becoming part of the University of Florida.[11] Columbia High School constructed a second building in 1906 that was used until 1922.

In 1907, Lake City officials leased the former property of the Florida Agricultural College to the Florida Baptist Convention; they founded a Baptist college called Columbia College. Columbia College lasted for ten years until the college became overwhelmed with debt. Columbia College deeded the land and buildings back to Lake City in 1919. During World War I, the campus of Columbia College was used as a training site for local troops for the war. The facility was adapted for use as U.S. Hospital No. 63, the predecessor of the Veterans Hospital constructed in Lake City. More than 34 Lake City soldiers were killed in World War I.[17]

In 1940, the population of Lake City was 5,836. During World War II, a number of institutions were established to help with the war effort as well as those in Lake City. The Lake Shore Hospital was dedicated in 1940 to provide medical care for those in the Lake City area. The Lake City Woman's Club became the United Service Organizations (USO) headquarters to entertain service personnel stationed in Lake City. Naval Air Station Lake City was commissioned in 1942 on the site of the Lake City Flying Club air field. NAS Lake City was a support facility for Naval Air Station Jacksonville and trained pilots to fly the Lockheed Ventura. Military operations at NAS Lake City ended in March 1946, and it was decommissioned as an active naval air station.[18]

After World War II a local air base was converted for use in 1947 as the Columbia Forestry School. The Columbia Forestry School had low enrollments and funds, forcing the school to seek help from the Florida legislature. The University of Florida assumed management of the school, and in 1950 it became the University of Florida Forest Ranger School. As part of the network of community colleges established in Florida, the school became the Lake City Junior College and Forest Ranger School in 1962. Lake City Junior College was renamed to Lake City Community College in 1970; in 2010, it was renamed as Florida Gateway College.[19]

By 1950, the population of Lake City was 7,571. The forestry products industry (turpentine, lumber, and pulpwood) had become a mainstay of the local economy.[11]

During the Korean War, five Lake City soldiers were killed. A monument was dedicated in 1985 in their honor and memory.

In 1958, the Columbia Amateur Radio Society[20] was formed. This was a group of amateur radio operators who enjoyed the ability to communicate all over the world. This radio club still exists today. Lake City's centennial was celebrated in 1959 with parades, fireworks, and a 58-page book documenting one hundred years of progress, A Century in the Sun. The citizens of the town dressed in period attire, complete with whiskers. A good-natured clash arose between the men with additional facial hair and the women who did not like it.[11]

In 1963, Interstate 75 and Interstate 10 were opened, intersecting at Lake City. In the 1960s, Columbia County schools were not desegregated. In 1970, a judge ordered all Columbia County public schools to integrate. During the Vietnam War, 23 local Lake City soldiers were either killed or M.I.A.[21]

In 1978, the Columbia County Public Library was established. Downtown Lake City was revitalized in the 1990s with new businesses, shops, and restaurants. In 2000, Lake City had a population of 9,980.

On 10 June 2019, Lake City was hit by a cyber ransomware attack that rendered many of the city's communication systems inoperable. On 25 June 2019, the City's insurance company, the Florida League of Cities, paid 42 bitcoins—over US$480,000—for a mechanism to retrieve the City's files and data.[22]

Geography

editLake City is located in northern Florida at 30°11′N 82°38′W (30.1896, –82.6397). It lies near the intersection of Interstate 10 and Interstate 75. Jacksonville is 60 miles (97 km) to the east, Tallahassee is 106 miles (171 km) to the west, Gainesville is 46 miles (74 km) to the south, and Valdosta, Georgia, is 62 miles (100 km) to the northwest.

According to the United States Census Bureau, Lake City has a total area of 12.4 square miles (32.2 km2), of which 12.0 square miles (31.1 km2) is land, and 0.39 square miles (1.0 km2) or 3.20%, is water.[23]

Climate

editLake City is part of the humid subtropical climate zone of the Southeastern United States. Due to its latitude and relative position north of Florida's peninsula it is subject at times to continental conditions, which cause rare cold snaps that may affect sensitive winter crops.[24] The hottest temperature ever recorded in the city was 106 °F (41 °C) on June 4, 1918, and the coldest temperature ever recorded was 6 °F (−14 °C) on February 13, 1899.[25]

| Climate data for Lake City, Florida, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

102 (39) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

96 (36) |

91 (33) |

91 (33) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 79.3 (26.3) |

81.8 (27.7) |

85.1 (29.5) |

89.2 (31.8) |

93.9 (34.4) |

96.8 (36.0) |

96.7 (35.9) |

95.5 (35.3) |

93.1 (33.9) |

89.0 (31.7) |

84.3 (29.1) |

80.4 (26.9) |

97.9 (36.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 63.2 (17.3) |

67.0 (19.4) |

73.1 (22.8) |

78.7 (25.9) |

85.2 (29.6) |

88.3 (31.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

88.8 (31.6) |

86.0 (30.0) |

79.4 (26.3) |

71.3 (21.8) |

65.5 (18.6) |

78.0 (25.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 52.1 (11.2) |

55.5 (13.1) |

60.8 (16.0) |

66.6 (19.2) |

73.4 (23.0) |

78.2 (25.7) |

80.0 (26.7) |

79.6 (26.4) |

76.6 (24.8) |

69.0 (20.6) |

60.2 (15.7) |

54.5 (12.5) |

67.2 (19.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 40.9 (4.9) |

44.0 (6.7) |

48.6 (9.2) |

54.5 (12.5) |

61.6 (16.4) |

68.1 (20.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

70.4 (21.3) |

67.3 (19.6) |

58.6 (14.8) |

49.1 (9.5) |

43.5 (6.4) |

56.4 (13.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 25.1 (−3.8) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

33.9 (1.1) |

42.2 (5.7) |

51.6 (10.9) |

63.2 (17.3) |

67.2 (19.6) |

67.6 (19.8) |

60.4 (15.8) |

44.7 (7.1) |

33.2 (0.7) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 7 (−14) |

6 (−14) |

19 (−7) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

49 (9) |

57 (14) |

59 (15) |

44 (7) |

32 (0) |

18 (−8) |

9 (−13) |

6 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.27 (108) |

3.23 (82) |

4.29 (109) |

3.55 (90) |

3.47 (88) |

7.55 (192) |

7.16 (182) |

7.28 (185) |

5.86 (149) |

2.50 (64) |

1.91 (49) |

2.91 (74) |

53.98 (1,371) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.2 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 14.7 | 15.7 | 17.0 | 11.5 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 9.9 | 128.1 |

| Source: NOAA[26][27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 131 | — | |

| 1860 | 659 | 403.1% | |

| 1870 | 964 | 46.3% | |

| 1880 | 1,379 | 43.0% | |

| 1890 | 2,020 | 46.5% | |

| 1900 | 4,013 | 98.7% | |

| 1910 | 5,032 | 25.4% | |

| 1920 | 3,341 | −33.6% | |

| 1930 | 4,416 | 32.2% | |

| 1940 | 5,836 | 32.2% | |

| 1950 | 7,571 | 29.7% | |

| 1960 | 9,465 | 25.0% | |

| 1970 | 10,575 | 11.7% | |

| 1980 | 9,257 | −12.5% | |

| 1990 | 10,005 | 8.1% | |

| 2000 | 9,980 | −0.2% | |

| 2010 | 12,046 | 20.7% | |

| 2020 | 12,329 | 2.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] | |||

Lake City first appeared in the 1850 U.S. Census as "Alligator", with a total recorded population of 131.[29]

| Race | Pop 2010[30] | Pop 2020[31] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 6,453 | 5,886 | 53.57% | 47.74% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 4,432 | 4,312 | 36.79% | 34.97% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 47 | 37 | 0.39% | 0.30% |

| Asian (NH) | 192 | 314 | 1.59% | 2.55% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 0 | 9 | 0.00% | 0.07% |

| Some other race (NH) | 25 | 91 | 0.21% | 0.74% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 247 | 493 | 2.05% | 4.00% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 650 | 1,187 | 5.40% | 9.63% |

| Total | 12,046 | 12,329 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 12,329 people, 4,569 households, and 2,321 families residing in the city.[32]

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 12,046 people, 4,650 households, and 2,558 families residing in the city.[33]

Religion

editAround 40% of the people of Lake City are affiliated with a religion. Evangelicalism is the largest religious affiliation with 27.9% followed by Protestant (4.7%), Black Protestantism (3.5%), Catholicism (2.4%) and other religions (1.6%). 59.8% are not affiliated with any religion.[34]

Mountaintop Ministries Worldwide, formerly End Time Ministries and commonly called End Timers, was established near Lake City by Charles Meade in 1984. The basis of the ministry was that Lake City would be the only place to survive Armageddon and believers were to stay in an underground bunker on Meade's property.[35]

Ancestry/ethnicity

editAs of 2016 the largest self-reported ancestry groups in Lake City, Florida are:[36]

| Largest single ancestries in 2016 (excluding Hispanic/Latino groups) |

Percent |

|---|---|

| English | 16.4% |

| Irish | 10.1% |

| German | 9.9% |

| Subsaharan African | 6.9% |

| Italian | 5.1% |

| American | 2.9% |

| French | 2.7% |

| Polish | 1.7% |

| West Indian | 1.5% |

| Scotch-Irish | 1.4% |

| Dutch | 1.1% |

| Norwegian | 1.1% |

| Scottish | 0.9% |

| Welsh | 0.6% |

Economy

editLake City and Columbia County are known as "The Gateway to Florida" because Interstate 75 runs through them, carrying a large percentage of Florida's tourist and commercial traffic. Lake City is the northernmost sizable town/city in Florida on Interstate 75 and the location where I-10 and I-75 intersect. Interstate 10 is the southernmost east-west major interstate highway and traverses the country from Jacksonville, Florida, to Santa Monica, California. U.S. 41 and U.S. 90 (the U.S. highway versions of I-75 and I-10) have intersected in Lake City since 1927, long before the Interstate highways were built. The city relies on travelers for a considerable part of its economy.

Lake City is the location of the Osceola National Forest's administrative offices.

Since 2000, three companies have begun large operations in Lake City: Hunter Panels, New Millennium and United States Cold Storage. Target built their first company-owned and third-party-operated perishable food distribution center in Lake City in 2008.[37]

In 2011, The top employers in the Lake City area are:[38]

| Rank | Company name | Business description | # Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Columbia County School System | Education/Schools/Training & Development Centers | 1,400 |

| 2 | VA Medical Center | Healthcare | 1,200 |

| 3 | Anderson Columbia Co., Inc. | Asphalt/Paving | 775 |

| 4 | PCS Phosphate | Manufacturer | 706 |

| 5 | HAECO | Aircraft Maintenance | 635 |

| 6 | Wal-Mart Supercenter | Retail Sales | 505 |

| 7 | Lake City Medical Center | Healthcare | 430 |

| 8 | Sitel | Call Center | 358 |

| 9 | Shands at Lake Shore | Healthcare | 353 |

| 10 | CCA - Lake City Correctional Facility | Correctional Facility | 279 |

| 11 | City of Lake City | Government | 260 |

| 12 | S&S Food Stores | Convenience Stores | 249 |

| 13 | Columbia County Manager | Government | 248 |

| 14 | Florida Gateway College | Education | 225 |

| 15 | Health Care Center of Lake City | Healthcare | 163 |

| 16 | Publix Super Markets, Inc. | Grocery Stores | 151 |

| 17 | Corbitt Manufacturing Co., Inc. | Manufacturer | 115 |

| 18 | New Millennium | Manufacturer | 82 |

| 19 | Target Food Distribution Center | Distribution | 78 |

Arts and culture

editOlustee Battle Festival

editEvery February since 1976, Lake City has hosted the Olustee Battle Festival and reenactment of the Battle of Olustee spanning three days. The festival begins with a memorial service at Oak Lawn Cemetery in Lake City to honor those who died from both sides on day one and ends with a reenactment at the Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park on day three. From day one to day three various activities from live entertainment to exhibits are on display in downtown Lake City and the Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park.[39]

Alligator Warrior Festival

editThe Alligator Warrior Festival is held each year on the weekend of the 3rd Saturday in October to recognize the early history of Columbia County prior to the Civil War.[40] The first Alligator Festival was held in 1995 at Olustee Park in downtown Lake City. Starting in 2010 the annual festival has been held at O'Leno State Park 20 miles (32 km) south of Lake City where the appropriate facilities exist for a full-scale battle reenactment, historic camping and large crowds.[40]

Parks and recreation

edit- Alligator Lake Park

- Falling Creek Falls

- Olustee Park

- Wilson Park

- Osceola National Park

- Southside Sports Complex

- Youngs Park

Government

editLake City is governed by a council/city manager form of government. The city council consists of five members, with four representing four city districts, while the Mayor serves at-large throughout all of Lake City. The administration of Lake City consists of The City Manager's Office, The Assistant City Manager, Human Resources, Procurement, Finance and Technology.[41]

The Lake City Police Department was founded around 1861 during the Civil War. The first fire department was established in 1883 to complement the police department. Argatha Gilmore was the Chief of Police in 2009 after serving 25 years with the Tallahassee Police Department.

-

Lake City Police Department vehicle

-

City Hall

Education

editThe Columbia County School District, the only school district in the entire county,[42] operates nine elementary schools, three middle schools, two high schools and an alternative school. Lake City also has one higher education institution, Florida Gateway College, that offers associate degrees and four-year bachelor's degrees.

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editAirport

editThe Lake City Gateway Airport is a local center of business. The airport is classified as a general aviation facility, but two on-site operations are somewhat unusual. HAECO (formerly TIMCO) is an aircraft modification and rehabilitation operation for large (B-727, 737 and Airbus A-320 A-319) civilian and military aircraft. The U.S. Forest Service uses C-130 transport aircraft in support of its forest fire-fighting operations in the southeastern United States.

Interstate

editU.S. Highways

edit

Railroad

editLake City was a scheduled stop for Amtrak's Sunset Limited between Los Angeles and Orlando from 1993 to 2005, when damage to railroad lines and bridges by Hurricane Katrina caused the curtailment of all service east of New Orleans,

Freight service is provided by the Florida Gulf & Atlantic Railroad, which acquired most of the former CSX main line from Pensacola to Jacksonville on June 1, 2019.

Notable people

edit- Brian Allen, NFL linebacker

- Blayne Barber, PGA golf player

- Jerome Carter, NFL safety

- Fred P. Cone, 27th Governor of Florida

- Grace Elizabeth, model[43]

- Shayne Edge, former Florida Gators and Pittsburgh Steelers punter

- Yatil Green, NFL wide receiver Miami Dolphins

- Harold Hart, NFL player

- Bertram Herlong, bishop, Episcopal Diocese of Tennessee

- Timmy Jernigan, NFL defensive tackle

- Michael Kirkman, MLB pitcher, World Series, Texas Rangers

- Kimberly Diane Leach, last victim of serial killer Ted Bundy

- Trey Marshall, NFL safety

- Martha Mier, pianist and composer

- Dwight Stansel, state representative and farmer

- John Franklin Stewart, MLB, 2nd base

- Pat Summerall, NFL placekicker, television sportscaster

- Jasin Todd, former Shinedown guitarist

- Laremy Tunsil, NFL offensive lineman

- Reinard Wilson, NFL linebacker

- Chubby Wise, fiddler

- Susie Wiles, daughter of Pat Summerall and incoming Chief-of-Staff to 47th U.S. President Donald Trump

References

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lake City, Florida

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 90.

- ^ "History". Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Morris; McCarthy, Kevin (2009). Lake City Florida: A Sesquicentennial Tribute. Nature Coast Publishing House. pp. 2–5.

- ^ Taylor, George (February 21, 2009). "Alligator Town Marker". George Lansing Taylor Collection Main Gallery. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ "Lake City". vivafl500.org. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ "Lake City Florida. Celebrating 150 Years. A Guide to the Sesquicentennial Celebration." Lake City, FL, 2009, pg. 21.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Morris (March 8, 2008). "Lake City's 150th birthday — time for a celebration". Lake City Reporter. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2008.

- ^ "Battle Unit Details - The Civil War (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ a b "Events Leading up to the Battle of Olustee". battleofolustee.org. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ^ "Olustee Battlefield". Florida Public Archaeology Network. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Morris; McCarthy, Kevin (2009). Lake City Florida: A Sesquicentennial Tribute. Nature Coast Publishing House. pp. 30–31.

- ^ "Lake City". vivafl500.org. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Morris; McCarthy, Kevin (2009). Lake City Florida: A Sesquicentennial Tribute. Nature Coast Publishing House. pp. 86–88.

- ^ Williams, Morris; McCarthy, Kevin (2009). Lake City Florida: A Sesquicentennial Tribute. Nature Coast Publishing House. pp. 159–170.

- ^ Summers, Susan (November 13, 1990). "Forest Technology Program, Lake City Community College: The Founding of a School, the Evolution of a College". Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ "The Columbia Amateur Radio Society". Nf4cq.com. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Morris; McCarthy, Kevin (2009). Lake City Florida: A Sesquicentennial Tribute. Nature Coast Publishing House. pp. 221–247.

- ^ "Lake City pays 42 bitcoin ransom to cyber attacker to restore hacked systems". June 25, 2019.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Lake City city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for". Weather Channel. October 12, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "1850 Census of Population: Florida" (PDF). Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Lake City city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Lake City city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Lake City city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Lake City city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Religion statistics for Lake City city (based on Columbia County data)". Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Klebnikov, Alex Heard and Peter (December 27, 1998). "Apocalypse Now. No, Really. Now!". The New York Times Magazine. The New York Times Company. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "Target Distribution Centers | Target Corporate". Pressroom.target.com. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ [1] Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Annual Olustee Festival". Olusteefestival.com. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ a b "Alligator Warrior Festival". Alligatorfest.org. November 9, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Mayor and Council". lcfla.com.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Columbia County, FL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 4, 2024. - Text list

- ^ "Get to Know Stunning Victoria's Secret Fashion Show Model Grace Elizabeth". maxim.com. December 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

External links

edit- City of Lake City official website

- Florida Index, historical newspaper for Lake City, Florida fully and openly available in the Florida Digital Newspaper Library