The Songs of Distant Earth is the sixteenth studio album by English musician, songwriter and producer Mike Oldfield, released on 21 November 1994 by WEA. It is a concept album[2] based on the 1986 science fiction novel The Songs of Distant Earth by Arthur C. Clarke.[3] The album reached No. 24 on the UK Albums Chart.

| The Songs of Distant Earth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 21 November 1994 | |||

| Recorded | 1993–1994 | |||

| Studio | Roughwood Croft, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 55:51 | |||

| Label | WEA | |||

| Producer | Mike Oldfield | |||

| Mike Oldfield chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Revised cover | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Songs of Distant Earth | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Allmusic | |

Background

editIn 1993, Oldfield completed his 1992–1993 tour to promote his previous album, Tubular Bells II (1992), his first concert tour since 1984. The album was his first of the initial three that he was contracted to produce for Warner Music UK, following his signing to the label in 1992.[4] When Oldfield was ready to record a follow-up, label chairman Rob Dickins suggested that he make a concept album based on the 1986 science fiction novel The Songs of Distant Earth by Arthur C. Clarke.[5] Oldfield deemed the story not one of Clarke's best, "but it had lots of atmosphere" and started to think of musical ideas on travelling through space and landing on another world and the events that take place on it.[5] The title of the book particularly attracted Oldfield, calling it "intrinsically musical, a natural starting point".[6][7] Oldfield visited Clarke in Sri Lanka to discuss the possibility and found out he was a fan of his soundtrack to the 1984 film The Killing Fields and felt "delighted" about the album. Clarke was given a copy of Tubular Bells II for listening; he was impressed enough and agreed to collaborate.[8]

Writing and recording

editOldfield chose to have the album follow the novel's plot "loosely".[6] It recounts the destruction of Earth in the year 3600 after the Sun goes nova, for which the planet has 1,600 years to prepare, sending spaceships to nearby planetary systems.[7] The album took longer for Oldfield to complete than he had initially planned, in part because he considered some of his usual instruments - including acoustic guitars - too "Earth-bound" for the setting, opting instead to create a "new vocabulary" of sounds in the studio.[6] This led Oldfield to broaden his repertoire and appeal, and resulted in an album which he classed as "very ambient".[9]

He made extensive use of samples, including from the sample CD Datafile One (1991) by Zero-G, Led Zeppelin's "When the Levee Breaks" (1971), film soundtracks, and world music recorded in Polynesia and Lapland.[9] While the album was being mixed and cut, Oldfield was concerned that being a solely digital recording, it would sound too "angular". As a test, a copy was made onto recording tape using Dolby SR, a type of noise reduction, which he thought produced some nice results but greater loss of clarity.[9] The liner notes contains a foreword by Clarke about the development of his book, from short story to novel. He ends it with a note about the album: "Since the finale of the novel is a musical concert, I was delighted when Mike Oldfield told me that he wished to compose a suite inspired by it. I was particularly impressed by the music he wrote for The Killing Fields and now, having played the CD-ROM of The Songs of Distant Earth, I feel he has lived up to my expectations. Welcome back into space, Mike: there's still lots of room out here."[10]

CD-ROM content

editOldfield faced difficulty in writing music to the story at first and needed some "in between space" to help visualise it. This was alleviated when he received a copy of the 1993 graphic adventure puzzle game Myst for the PC and was impressed with the graphics, which greatly influenced his decision to have 3D computer-generated video accompany the music for the album on the Enhanced CD format, combining features of a standard CD with CD-ROM content. The result was graphics that Oldfield had in his mind while writing the music.[11] Oldfield felt contemporary music at the time of recording lacked any real excitement, but felt the reverse as he worked on the interactive technology. This, and his interest in Myst, sparked his wish to make his own game that helped the player on their own spiritual development.[7] While composing for the CD-ROM Oldfield had trouble adapting a theme by Jean Sibelius for it, which turned into a rage where be "banged out a theme. Like a sort of miracle, it worked!"[7]

The CD-ROM allows users to travel through a futuristic city on board a spaceship and towards a central control system, inside of which houses a musical tower. The user must answer a musical puzzle which provides a series of options that trigger a different song on the album.[7]

Release

editThe album was released in the UK on 21 November 1994. It went to No. 24 on the UK Albums Chart and reached gold certification by the British Phonographic Industry. Its US release followed in January 1995 on Reprise Records.[11][12]

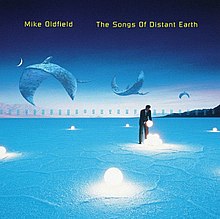

The album was released as a CD and, shortly afterwards, as an Enhanced CD of which two versions were made. Both versions' initial pressings contained an image of a manta ray flying in front of a planet on the front cover; later pressings change the image to one of a suited man holding a glowing orb with manta rays flying overhead. The second pressing of the enhanced CD contains slightly more multimedia content, including the full version of the "Let There Be Light" video. The CD audio content is the same on all versions of the album. It was also released as a vinyl LP, which has become a rare item.

The enhanced CD content, for Apple Macintosh PowerPC computers only, was rendered on Silicon Graphics computers and used Apple's QuickTime II technology.[13] The re-release back cover lists the "CD ROM Track" as track 000 (where all tracks have a three-digit number), and a length of 0:00. Produced in 1994 it was an early example of Enhanced CD content.[14]

Oldfield used Emagic Logic Audio for sequencing and Pro Tools hardware for the recording of the album using a combination of tape and hard drive recording.[15]

Track listing

edit- "In the Beginning" – 1:24

- "Let There Be Light" – 4:52

- "Supernova" – 3:29

- "Magellan" – 4:41

- "First Landing" – 1:16

- "Oceania" – 3:27

- "Only Time Will Tell" – 4:19

- "Prayer for the Earth" – 2:10

- "Lament for Atlantis" – 2:44

- "The Chamber" – 1:49

- "Hibernaculum" – 3:32

- "Tubular World" – 3:23

- "The Shining Ones" – 2:59

- "Crystal Clear" – 5:42

- "The Sunken Forest" – 2:39

- "Ascension" – 5:48

- "A New Beginning" – 1:33

Personnel

editMusic

- Mike Oldfield – various instruments

- Eric Caudieux – additional programming

- Mark Rutherford – additional rhythm loops

- Sugar "J" – additional rhythm loops

- Pandit Dinesh – tablas

- Molly Oldfield – keyboards

- Cori Josias – vocals

- Ella Harper – vocals

- David Nickless – vocals

- Roame – vocals

- Nils-Aslak Valkeapää – Sámi chant for a joik on "Prayer for the Earth"

- Members of Verulam Consort – vocals

- Tallis Scholars – vocals

Excerpts:

- Bill Anders – reading from the Book of Genesis while orbiting the Moon on Christmas Eve, 1968 on "In the Beginning"[10]

- "Vahine Taihara" by Tubuai Choir

- Mike Joseph – self hypnosis tape on "Crystal Clear"

Production

- Mike Oldfield – production, engineer

- Gregg Jackman – assistant engineer

- Steve MacMillan – assistant engineer

- Tom Newman – assistant engineer

- Richard Barrie – technical engineer

- Bill Smith Studio – design, art direction

- Simon Fowler – portrait photography

Certifications and sales

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[16] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[17] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Summaries | ||

| Worldwide | — | 750,000[18] |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

edit- ^ The Songs of Distant Earth review at AllMusic

- ^ "Mike Oldfield: Recording Songs Of Distant Earth". soundonsound.com. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Notes about Tubular Bells II". Tubular.net. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- ^ Oldfield 2008, p. 248.

- ^ a b Oldfield 2008, p. 244.

- ^ a b c "Promotional blurb for 'The Songs of Distant Earth'". WEA. 1994. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Salem, Charlie (February 1995). "Totally Tubular". Internet and Comms Today. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Pre-release promotional blurb for 'The Songs of Distant Earth'". WEA. 1994. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b c White, Paul (February 1995). "Tubular Worlds". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b Arthur C. Clarke (1994). The Songs of Distant Earth (Mike Oldfield vinyl LP cover). Warner Music UK Ltd. 4509-98581-1.

- ^ a b Gillen, Marilyn A. (5 November 1994). "Oldfield Pioneers Music/Cyberspace Border". Billboard. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "The Songs Of Distant Earth Press Release". WEA. 30 November 1994. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ The Songs of Distant Earth (Mike Oldfield CD cover). Warner Music UK Ltd. 1994. 4509-98581-1.

- ^ "Mike Oldfield". Sound on Sound. November 2002. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Paul White (February 1995). "Tubular Worlds". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Salaverrie, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (PDF) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Fundación Autor/SGAE. p. 940. ISBN 84-8048-639-2. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "British album certifications – Mike Oldfield – The Songs of Distant Earth". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Who Is Selling Where". Billboard. 17 February 1996. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

Sources

- Oldfield, Mike (2008). Changeling - Autobiography of Mike Oldfield. Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-753-51307-1.