On 21 September 1976, Orlando Letelier, a leading opponent of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, was assassinated by car bombing, in Washington, D.C. Letelier, who was living in exile in the United States, was killed along with his colleague Ronni Karpen Moffitt, who was in the car with her husband Michael.[1] The assassination was carried out by agents of the Chilean secret police (DINA), and was one among many carried out as part of Operation Condor. Declassified U.S. intelligence documents confirm that Pinochet directly ordered the killing.[2]

| Assassination of Orlando Letelier | |

|---|---|

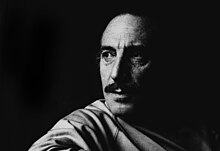

Letelier in 1976 | |

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Date | September 21, 1976 9:30 am (UTC-04:00) |

| Target | Orlando Letelier |

Attack type | Car bombing |

| Deaths | 2 |

| Injured | 1 |

| Perpetrators | DINA |

Background

editIn 1971, Letelier was appointed ambassador to the United States by Salvador Allende, the socialist president of Chile.[3] Letelier had lived in Washington, D.C., during the 1960s and had supported Allende's campaign for the presidency. Allende believed Letelier's experience and connections in international banking would be highly beneficial to developing US–Chile diplomatic relations.[4] During 1973, Letelier served successively as Minister of Foreign Affairs, then Interior Minister, and, finally, Defense Minister. After the Chilean coup of 1973 that brought Augusto Pinochet to power, Letelier was one of the first members of the Allende administration to be arrested by the Chilean government and sent to a political prison in Tierra del Fuego.

He was held for 12 months in different concentration camps and suffered severe torture: first at the Tacna Regiment, then at the Military Academy. Later, he was sent to a political prison for eight months at Dawson Island. From there, he was transferred to the basement of the Air Force War Academy, and finally to the concentration camp of Ritoque. Eventually, international diplomatic pressure, especially from Diego Arria, then Governor of the Federal District of Venezuela, and United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger[5] resulted in Letelier's sudden release on the condition that he immediately leave Chile for Venezuela. He was told by the officer in charge of his release that "the arm of DINA is long; General Pinochet will not and does not tolerate activities against his government." This was a clear warning to Letelier that living outside of Chile would not guarantee his safety.[6]

After his release in 1974, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he became a senior fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies, an independent international policy studies think tank.[7] He plunged into writing, speaking and lobbying the US Congress and European governments against Augusto Pinochet's regime, and soon he became the leading voice of the Chilean resistance, in the process preventing several loans (especially from Europe) from being awarded to the military government. He was described by his colleagues as being "the most respected and effective spokesman in the international campaign to condemn and isolate" Pinochet's government.[8] Letelier was assisted at the Institute for Policy Studies by Ronni Moffitt, a 25-year-old fundraiser who ran a "Music Carryout" program that produced musical instruments for the poor, and also campaigned for democracy in Chile.[9]

Letelier soon became a person of interest for Operation Condor, a campaign initiated by right-wing governments in South America to gather intelligence on opposition movements and to assassinate the leaders of these movements. Former General and political figure Carlos Prats, who had become a vocal opponent of the Pinochet government,[10] was killed in Buenos Aires by a radio-controlled car bomb on September 30, 1974, in an assassination planned and executed by members of DINA.[11] Letelier's pro-democracy campaign and his vehement criticisms of Pinochet had been under watch by the Chilean government. Letelier became a target in DINA director Manuel Contreras' efforts to eliminate resistance to the Pinochet government.[12]

In October 1975, Letelier became the Director of Planning and Development for the International Political Economy Programme of the Transnational Institute, an international think tank for progressive politics affiliated with the Institute for Policy Studies. Through the institute's operations in the Netherlands, Letelier convinced the Dutch government not to invest US$63 million in the Chilean mining industry.[13][14] On 10 September 1976, the Chilean government revoked Letelier's Chilean citizenship. Pinochet signed a decree declaring that the former ambassador's citizenship be canceled due to his interference "with normal financial support to Chile"[13] and his efforts "to hinder or prevent the investment of Dutch capital in Chile".[14] Later that day, in a speech delivered at the Felt Forum in Madison Square Garden, Letelier proclaimed:

Today Pinochet has signed a decree in which it is said that I am deprived of my nationality. This is an important day for me. A dramatic day in my life in which the action of the fascist generals against me makes me feel more Chilean than ever. Because we are the true Chileans, in the tradition of O'Higgins, Balmaceda, Allende, Neruda, Gabriela Mistral, Claudio Arrau and Victor Jara, and they – the fascists – are the enemies of Chile, the traitors who are selling our country to foreign investments. I was born a Chilean, I am a Chilean and I will die a Chilean. They were born traitors, they live as traitors and they will be known forever as fascist traitors.[15]

Attack

editOrlando Letelier was driving to work in Washington, D.C., on 21 September 1976, with Ronni Moffitt (January 10, 1951 – September 21, 1976) and her husband of four months, Michael. Letelier was driving, while Moffitt was in the front passenger seat, and Michael was in the back behind his wife.[16] As they rounded Sheridan Circle in Embassy Row at 9:35 am EDT, an explosion erupted under the car, lifting it off the ground. When the car came to a halt after colliding with a Volkswagen illegally parked in front of the Irish Embassy, Michael was able to escape from the rear end of the car by crawling out of the back window. He then saw his wife stumbling away from the car and, assuming that she was safe, went to assist Letelier, who was still in the driver seat,[17] barely conscious and appearing to be in great pain. Letelier's head was rolling back and forth, his eyes moved slightly, and he muttered unintelligibly.[citation needed] Michael tried to remove Letelier from the car, but was unable to do so, despite the fact that much of Letelier's lower torso was blown away and his legs had been severed.[18]

Both Ronni Moffitt and Orlando Letelier were taken to the George Washington University Medical Center shortly thereafter. At the hospital, it was discovered that Ronni's larynx and carotid artery had been severed by a piece of flying shrapnel.[18] She drowned in her own blood some 30 minutes after Letelier's death,[17] while Michael suffered only a minor head wound. Michael estimated the bomb was detonated at approximately 9:30 am; the medical examiner report set the time of Letelier's death at 9:50 am and Moffitt's at 10:37 am, the cause of death for both listed as explosion-incurred injuries due to a car bomb placed under the car on the driver's side.[citation needed]

Diego Arria intervened once again by bringing Letelier's body to Caracas, Venezuela, for burial, where it remained until the end of Pinochet's rule.

Cover-up effort

editA United States Department of Justice affidavit from August 23, 1991 detailed the efforts of the Pinochet regime to cover up its role in the assassinations of Letelier and Moffitt.[19] The extensive efforts were codenamed "Operación Mascarada".[19]

Investigation and prosecution

editInvestigators initially determined that the explosion was caused by a plastic explosive, molded to concentrate the force of its blast into the driver's seat. The bomb was attached by wires or magnets to the car's underside, and blew a "circular hole, 2 to 2½ feet in diameter" in the driver's seat.[16] The bomb was not believed to have been controlled by a timing device or a remote-controlled detonator.[16]

In the days after the incident, spokespersons for the United States Department of State said the department "expresses its gravest concern about Dr. Orlando Letelier's death".[5] Due to the assassination of Prats and the attempted assassination of Bernardo Leighton, the incident was believed to have been the latest of a series of state-sponsored assassination attempts against Chilean political exiles.[5] A spokesman for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) said that this was the first incident of violence against Chilean exiles on American soil, according to agency records.[5]

The FBI eventually uncovered evidence that Michael Townley, a DINA US expatriate, had organized the assassination of Orlando Letelier on behalf of Chile. Townley and Armando Fernandez Larios, who was also implicated in the murder, had been given visas to enter the United States.

In 1978, Chile agreed to turn Townley over to the United States, where he began to testify extensively. Townley pleaded guilty and confessed that he had contacted five anti-Castro Cuban exiles to help him booby-trap Letelier's car. According to Jean-Guy Allard, after consultations with the Coordination of United Revolutionary Organizations (CORU) leadership, including Luis Posada Carriles and Orlando Bosch, those elected to carry out the murder were Cuban-Americans José Dionisio Suárez Esquivel,[20] Virgilio Paz Romero, Alvin Ross Díaz, and brothers Guillermo and Ignacio Novo Sampol.[citation needed] According to the Miami Herald, Luis Posada Carriles was at this meeting, which formalized details that led to Letelier's death and also the Cubana bombing two weeks later. Townley also agreed to provide evidence against these men in exchange for a deal that involved his pleading guilty to a single charge of conspiracy to commit murder and being given a ten-year sentence. His wife, Mariana Callejas, also agreed to testify in exchange for not being prosecuted. In later time, it was acknowledged that Townley intended to leave Chile so he could seek protection from Manuel Contreras and his deputy Pedro Espinoza.[19]

On January 9, 1979, the trial of the Novo Sampol brothers and Díaz began in Washington, D.C. All three were found guilty of murder. Guillermo Novo and Díaz were sentenced to life imprisonment. Ignacio Novo received eight years. However the three were acquitted at a new trial. Townley served about half of a 10-year sentence and was freed under the Witness Protection Program. Dionisio Suarez and Virgilio Paz remained fugitives until they were apprehended in the 1990s. They pleaded guilty and served short sentences.

In 1987, Larios fled Chile with the assistance of the FBI, claiming he feared that Pinochet was planning to kill him because he refused to co-operate in cover-up activities related to the Letelier murder. On February 4, 1987, Larios pleaded guilty to one count of acting as an accessory to the murder. In exchange for the plea and information about the plot, the authorities dropped the charges.

Several other people were also prosecuted and convicted for the murder. Among them were General Manuel Contreras, former head of the DINA, and Brigadier Pedro Espinoza Bravo, also formerly of the DINA. Contreras and Espinoza were convicted in Chile on November 12, 1993, and sentenced to seven and six years of prison respectively.

In 2000, 16,000 documents that were previously secret were released by various United States government departments and agencies as part of an effort to declassify materials related to political violence and human rights violations from the late 1960s to early 1990s in Chile.[21] According to United States Department of State, Pinochet called fellow right-wing president, Paraguayan General Alfredo Stroessner, in 1976 and requested that Townley and Fernandez Larios received passports with phony names.[21] Almost immediately after stamping the visas, State Department officials realized the passports had been falsely obtained and canceled the visas; however, Townley and Fernandez Larios were able to enter the US in August 1976.[21]

Pinochet, who died on December 10, 2006, was never charged in relation to this case.

Diplomatic resolution of civil liability

editThe Chilean government pushed back against efforts by the Letelier and Moffitt families for judicial determinations of civil liability to be made in the United States.[22]

As Chile was unwilling to submit to a determination by a U.S. tribunal, a State Department principal deputy legal advisor, Michael Kozak, originated an idea to settle the dispute invoking the arbitration clause of the 1914 Chile-United States peace treaty.[22][23]

Chile agreed and in the early 1990s the arbitration commission determined the amounts of the payments to be made to the families.[23]

Allegations of U.S. foreknowledge

editAccording to John Dinges, author of The Condor Years (The New Press 2003), documents released in 2015 revealed a CIA report dated April 28, 1978 that showed the agency by then had knowledge that Pinochet ordered the murders.[24] The report stated “Contreras told a confidant he authorized the assassination of Letelier on orders from Pinochet."[24] A State Department document also referred to eight separate CIA reports from around the same date, each sourced to “extremely sensitive informants” who provided evidence of Pinochet’s direct involvement in ordering the assassination and in directing the subsequent cover-up.[24] FBI Carter Cornick, an FBI special agent credited with solving the case with his partner Robert Scherrer, said that the information was hearsay gathered from people who might provide the CIA with information but would never appear in court.[24] However, documented Michael Townley confessions which were published by the National Security Archive in November 2023 indicated that DINA head Manuel Contreras was in fact the one who ordered the assassination.[25] Townley even at point sent Contreas a letter where he accused him of misleading Pinochet on details surrounding the assassination.[26][25]

When Townley and his Chilean associate tried to obtain B-2 visas to the United States in Paraguay, Landau was told by Paraguayan intelligence that these Paraguayan subjects were to meet with General Vernon A. Walters in the United States, concerning CIA business. Landau was suspicious of this declaration, and cabled for more information. The B-2 visas were revoked by the State Department on August 9, 1976.[27] However, under the same names, two DINA agents used fraudulent Chilean passports to travel to the U.S. on diplomatic A-2 visas, in order to shadow Letelier.[27][28] Townley himself flew to the U.S. on a fraudulent Chilean passport and under another assumed name. Landau had made copies of the visa applications though, which later documented the relationship of Townley and DINA with the Paraguayan visa applications.

According to Dinges, documents released in 1999 and 2000 establish that "the CIA had inside intelligence about the assassination alliance at least two months before Letelier was killed, but failed to act to stop the plans." The intelligence was about Condor's plans to kill prominent exiles outside of Latin America, but did not specify Letelier was the target. It also knew about an Uruguayan attempt to kill U.S. Congressman Edward Koch, which then-CIA director George H. W. Bush warned him about only after Orlando Letelier's murder.[citation needed]

Kenneth Maxwell claims that U.S. policymakers were aware not only of Operation Condor in general, but in particular "that a Chilean assassination team had been planning to enter the United States." A month before the Letelier assassination, Kissinger ordered "that the Latin American rulers involved be informed that the 'assassination of subversives, politicians and prominent figures both within the national borders of certain Southern Cone countries and abroad ... would create a most serious moral and political problem." Maxwell wrote in his review of Peter Kornbluh's book, "This demarche was apparently not delivered: the U.S. embassy in Santiago demurred on the ground that to deliver such a strong rebuke would upset the dictator", and that, on September 20, 1976, the day before Letelier and Moffitt were killed, the State Department instructed the ambassadors to take no further action with regard to the Condor scheme. [Maxwell, 2004, 18].

On April 10, 2010, the Associated Press reported that a document discovered by the National Security Archive indicated that the State Department communique that was supposed to have gone out to the Chilean government warning against the assassinations had been blocked by then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.[29]

During the FBI investigation into the assassination, documents in Letelier's possession were copied and leaked to journalists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak of The Washington Times and Jack Anderson by the FBI before being returned to his widow.[30] The documents purportedly show Letelier was working with Eastern Bloc Intelligence agencies for a decade and coordinating his activities with the surviving political leadership of the Popular Unity coalition exiled in East Berlin.[31] The FBI suspected that these individuals had been recruited by the Stasi.[32] Documents in the briefcase showed that Letelier had maintained contact with Salvador Allende’s daughter, Beatriz Allende who was married to Cuban DGI station chief Luis Fernandez Ona.[31][33]

The documents showed Letelier was receiving $5,000 a month from the Cuban government and under the supervision of Beatriz Allende, he used his contacts within the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS),[33][34] and western human rights groups to organize a campaign within the United Nations as well as the US Congress to isolate the new Chilean government[33] This organized pressure on Pinochet’s government was allegedly closely coordinated by the Cuban and Soviet governments, perhaps using individuals like Letelier to implement these efforts. Letelier's briefcase also contained his address book containing the names of dozens of known and suspected Eastern Bloc intelligence agents. Correspondence between Letelier and individuals in Cuba had been handled via Julian Rizo, who used his diplomatic status to hide his activities.[32][35]

Fellow IPS member and friend Saul Landau described Evans and Novak as part of an “organized right wing attack”. In 1980, Letelier's widow, Isabel, wrote in The New York Times that the money sent to her late husband from Cuba was from western sources, and that Cuba had simply acted as an intermediary,[36] although Novak and Evans point out that the documents from Beatriz Allende were very clear on the source of the money.[33]

Around the time he was identified as a murder suspect in the U.S. and Chilean press in March 1978, Townley, using the alias J. Andres Wilson, sent a letter to Contreas where he issued a series of bitter complaints about the operational mistakes in the Letelier assassination mission that had led to his public identification.[26][25] Townley also claimed Contreras had not “let his Excellency [Pinochet] know the truth about this case.”[26][25] In one of his first "confession" letters that he wrote the same month, Townley acknowledged that he was in fact employed by DINA and was "following orders from Gen. Contreas" when he carried out the assassination.[37] In a letter dated March 14, 1976, Townley recounted how he received orders to carry out the assassination from Contreas' deputy Pedro Espinoza, and later also added that he in fact recruited the assassination team composed of American Cuban exiles after entering the U.S. on false visas he obtained in Paraguay.[38] However, Townley stated that his source of foreign assistance was in fact the so-called “Red Condor,” the Condor network of Southern Cone secret police services.[38]

In popular culture

editBritish film director Alan Clarke was in the pre-production stages of making the story into a film titled Assassination on Embassy Row, based on Saul Landau's book of the same title. Whilst putting the film together in the US, Clarke was diagnosed with lung cancer and returned to the United Kingdom. Following Clarke's death in 1990, the project was shelved.

A minor character in the 1983 film Scarface, Dr. Orlando Gutiérrez, was based on Letelier.[39] Gutiérrez is a Bolivian investigative journalist who intends to expose the ties between the corrupt Bolivian military junta and drug lord Alejandro Sosa (based on Roberto Suárez Gómez). Tony Montana and one of Sosa's henchmen plant a bomb in Gutiérrez' car, planning to detonate it in front of the United Nations Building in New York, but Montana changes his mind at the last minute and kills the henchman.

The 1986 novel Waking the Dead (which was adapted into film in 2000) includes a car bomb placed on American soil by Chilean operatives.

See also

edit- Attempted assassination of Bernardo Leighton

- Chilean political scandals

- Chile under Pinochet

- Eugenio Berríos, DINA biochemist who allegedly produced the explosive used in the bombing

- List of incidents of political violence in Washington, D.C.

- National Security Archive

- Operation Condor

- United States and state-sponsored terrorism

- United States and state terrorism

Notes

edit- ^ John, Dinges; Landau, Saul (September 16, 2014) [Pantheon Books, first edition January 1, 1980]. Assassination on Embassy Row. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-0394508023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Pinochet directly ordered killing on US soil of Chilean diplomat, papers reveal Archived November 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. October 8, 2015.

- ^ McCann 2006, p. 132.

- ^ McCann 2006, p. 133.

- ^ a b c d Binder, David (September 22, 1976). "Opponent of Chilean Junta Slain In Washington by Bomb in His Auto". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

His release from prison resulted in large part from intervention by Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger.

- ^ Dinges & Landau 1981, p. 83.

- ^ McCann 2006, p. 134.

- ^ Kornbluh, Peter (2004), The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability, New York: The New Press, p. 349, ISBN 1-56584-936-1, OCLC 56633246.

- ^ The Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Awards, Institute for Policy Studies, archived from the original on August 29, 2019, retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ "Chilean agent convicted over Prats' killing", BBC News, November 20, 2000, archived from the original on July 26, 2008, retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ^ Nagy-Zekmi, Silvia; Leiva, Fernando (2004), Democracy in Chile: The Legacy of September 11, 1973, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, p. 180, ISBN 1-84519-081-5, OCLC 60373757.

- ^ McCann 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ^ a b Diuguid, Lewis H. (September 16, 1976), "Chile Decree Lifts Citizenship Of Ex-Ambassador Letelier", The Washington Post, p. A30.

- ^ a b Letelier's Trips to Holland and the Stevin Group Affair, Transnational Institute, November 17, 2005, archived from the original on April 16, 2013, retrieved August 9, 2012

- ^ Transcript of Orlando Letelier's Speech at the Felt Forum, Madison Square Garden on September 10, 1976, Transnational Institute.

- ^ a b c Lynton, Stephen J.; Meyer, Lawrence (September 22, 1976), "Ex-Chilean Ambassador Killed by Bomb Blast", The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Orlando Letelier: Murdered in central Washington DC Archived August 2, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. BBC. 21 September 2011

- ^ a b John Dinges. The Condor Years: How Pinochet And His Allies Brought Terrorism To Three Continents. The New Press, 2005. p. 7 Archived May 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 1565849779

- ^ a b c Marcy, Eric B. (August 23, 1991). "Department of Justice, "Draft; Marcy/Letelier/Affidavit," August 23, 1991 [Original in English and Spanish translation]". National Security Archive. Archived from the original on November 25, 2023. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Cova, Antonio de la. "Jose Dionisio Suarez Esquivel". Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c Loeb, Vernon (November 14, 2000). "Documents Link Chile's Pinochet to Letelier Murder". The Washington Post. p. A16. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Scharf, Michael P.; Williams, Paul R. (2010). Shaping Foreign Policy in Times of Crisis: The Role of International Law and the State Department Legal Adviser. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-521-16770-3. LCCN 3009036861.

kozak.

- ^ a b Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (January 1992). "Chile-United States Commission Convened Under the 1914 Treaty for the Settlement of Disputes: Decision with Regard to the Dispute Concerning Responsibility for the Deaths of Letelier and Moffitt". International Legal Materials. 31 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1017/S0020782900018404. S2CID 249001496.

- ^ a b c d AM, John Dinges On 10/14/15 at 11:23 (October 14, 2015). "A Bombshell on Pinochet's Guilt, Delivered Too Late". Newsweek. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "The Pinochet Dictatorship Declassified: Confessions of a DINA Hit Man". National Security Archive. November 22, 2023. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c Wilson, J. Andreas (March 1, 1978). "Townley Papers, "Dear Don Manuel" [letter from Townley to DINA chief General Manuel Contreras], Undated [Spanish original and English translation]". National Security Archives. Archived from the original on November 25, 2023. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ a b U.S. State Department (September 1, 1976). "Issuance of Visas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ^ U.S. State Department (September 1, 1976). "Visas to Enter United States under False Pretenses" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- ^ "Cable Ties Kissinger to Chile Scandal". Associated Press in The Boston Globe. April 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

As secretary of state, Henry Kissinger canceled a U.S. warning against carrying out international political assassinations that was to have gone to Chile and two neighboring nations just days before a former ambassador was killed by Chilean agents on Washington's Embassy Row in 1976, a newly released State Department cable shows.

- ^ Lee Lescaze. “Letelier Briefcase Opened to Press”, The Washington Post. Feb 17, 1977

- ^ a b Jack Anderson and Les Whitten. “Letelier's 'Havana Connection' ”, The Washington Post, Dec 20, 1976

- ^ a b Robert Moss, The Letelier Papers. Foreign Report; March 22, 1977

- ^ a b c d Roland Evans and Robert Novak, Letelier Political Fund. The Washington Post; February 16, 1977

- ^ Jack Anderson and Les Whitten. “Letelier's 'Havana Connection'”, The Washington Post, Dec 20, 1976

- ^ Roland Evans and Robert Novak, Behind the Murder of Letelier. Indianapolis News; March 1, 1977

- ^ Isabel, The Revival of Old Lies about Orlando Letelier. The New York Times; November 8, 1980

- ^ Townley, Michael (March 13, 1978). "Townley Papers, "Confesión y Acusación [Confession and Accusation]," March 13, 1978". National Security. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Townley, Michael (November 25, 2023). "Townley Papers, "Relato de Sucesos en la Muerte de Orlando Letelier el 21 de Septiembre, 1976 [Report of Events in the Death of Orlando Letelier, September 21, 1976]," March 14, 1976". National Security Archive. Archived from the original on November 25, 2023. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Stevenson, Damian (2015). Scarface: The Ultimate Guide. Lulu.com. p. 75. ISBN 978-1329305236.

References

edit- Dinges, John; Landau, Saul (1981), Assassination on Embassy Row, New York: Pantheon Books, ISBN 0-394-50802-5, OCLC 6144488.

- Dinges, John (2004), The Condor Years: How Pinochet and his Allies brought Terrorism to Three Continents, New York: The New Press, ISBN 1-56584-764-4, OCLC 52846073.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2001), The Trial of Henry Kissinger, New York: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-631-9, OCLC 46240330.

- McCann, Joseph T. (2006), Terrorism on American Soil: A Concise History of Plots and Perpetrators from the Famous to the Forgotten, Boulder: Sentient Publications, ISBN 1-56584-936-1, OCLC 70866968.

- Branch, Taylor; Propper, Eugene (1982), Labyrinth, New York: Viking Press, ISBN 0-670-42492-7, OCLC 8110876.

External links

edit- Michael Townley and the Death of Orlando Letelier

- Orlando Letelier Archive held by the Transnational Institute.

- MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base Nine legal documents from the trials of Letelier's assassins. Includes trial transcripts.

- Institute for Policy Studies, where Letelier and Moffitt worked at the time, gives circumstances surrounding bombing.

- John Dinges John Dinges was a correspondent for The Washington Post in South America from 1975 to 1983, author of The Condor Years: How Pinochet and his Allies Brought Terrorism to Three Continents (The New Press 2004) and (with Saul Landau) Assassination on Embassy Row (Pantheon 1980), (Asesinato en Washington, Lasser 1980, Planeta 1990)

- National Security Archive page with documents and information about Latin America

- New Docs Show Kissinger Rescinded Warning on Assassinations Days Before Letelier Bombing – video report by Democracy Now!

- Washington Knew Pinochet Ordered an Act of Terrorism on US Soil – but Did Nothing About It. Peter Kornbluh for The Nation. September 21, 2016.