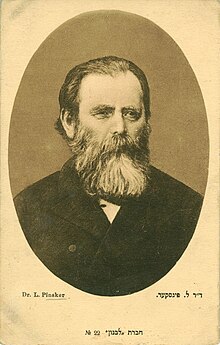

Leon Pinsker[a] or Judah Leib Pinsker (Hebrew: יהודה לייב פינסקר; Russian: Йехуда Лейб Пинскер; 25 December [O.S. 13 December] 1821 – 21 December [O.S. 9 December] 1891) was a physician and Zionist activist.

Leon Pinsker | |

|---|---|

| Лев Пинскер לעאָן פינסקער | |

| |

| Born | 13 December 1821 Tomaszów Lubelski, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 9 December 1891 (aged 69) Odessa, Russian Empire |

| Education | Law |

| Alma mater | Odessa University |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, political activist |

| Known for | Zionism |

| Movement | Hovevei Zion (Zionism) |

Earlier in life he had originally supported the cultural assimilation of Jews in the Russian Empire. He was born in the town of Tomaszów Lubelski in the southeastern border region of the Kingdom of Poland, and educated in Odessa, where he studied law but was unable to practice because of restrictions on occupations available to Jews.

Pinsker was a supporter of equal rights under the law for Jews, but his optimism was curtailed after the Odessa Pogroms. In response to the pogroms of 1871 and 1881, Pinsker founded the Zionist organization Hibbat Zion in 1881.

Political disagreements between religious and secular factions of the Odessa Committee, and Ottoman restriction on Jewish emigration, prevented Pinsker from resettling, and he died in Odessa in 1891. His remains were later brought to Jerusalem in 1934.

Biography

editLeon (Yehudah Leib) Pinsker inherited a strong sense of Jewish identity from his father, Simchah Pinsker, a Hebrew language writer, scholar and teacher. Leon attended his father's private school in Odessa and was one of the first Jews to attend Odessa University, where he studied law. Later he realized that, being a Jew, he had no chance of becoming a lawyer due to strict quotas on Jewish professionals and chose the career of a physician.

Jewish and Zionist activism

editPinsker believed that the Jewish problem could be resolved if the Jews attained equal rights. In his early years, Pinsker favored the assimilation path and was one of the founders of a Russian language Jewish weekly (see also: Haskala).

The Odessa pogrom of 1871 moved Pinsker to become an active public figure. In 1881, a bigger wave of anti-Jewish hostilities, many state-sponsored, swept southern Russia and continued until 1884. Then Pinsker's views changed radically, and he no longer believed that mere humanism and Enlightenment would defeat antisemitism.[1] In 1884, he organized an international conference of Hibbat Zion in Katowice (Upper Silesia, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia).[2]

As a professional physician, Pinsker preferred the medical term "Judeophobia" to the recently introduced "antisemitism". Pinsker knew that a combination of mutually exclusive assertions is a characteristic of a psychological disorder and was convinced that pathological, irrational phobia may explain this millennia-old hatred, wherein:

... to the living, the Jew is a corpse, to the native a foreigner, to the homesteader a vagrant, to the proprietary a beggar, to the poor an exploiter and a millionaire, to the patriot a man without a country, for all a hated rival.

His visit to Western Europe led to his famous pamphlet Auto-Emancipation, subtitled Mahnruf a seine Stammgenossen, von einem russischen Juden (Warning to His Fellow People, from a Russian Jew), which he published anonymously in German on 1 January 1882, and in which he urged the Jewish people to strive for independence and national consciousness.[3]

In his 1882 pamphlet Auto-Emancipation, Pinsker argued against Palestine as the destination for a Jewish commonwealth:

We must not attach ourselves to the place where our political life was once violently interrupted and destroyed. The goal of our present endeavors must be not the 'Holy Land', but a land of our own. We need nothing but a large piece of land for our poor brothers; a piece of land which shall remain our property, from which no foreign master can expel us. Thither we shall take with us the most sacred possessions which we have saved from the shipwreck of our former father-land, the God-idea and the Bible. It is only these which have made our old father-land the Holy Land, and not Jerusalem or the Jordan. Perhaps the Holy Land will again become ours. If so, all the better, but first of all, we must determine—and this is the crucial point—what country is accessible to us, and at the same time adapted to offer the Jews of all lands who must leave their homes a secure and unquestioned refuge, capable of being made productive.[4]

Despite being urged several times to amend his essay to say that Palestine was the only acceptable Jewish refuge, Pinkser refused, even writing in his will that he had not retracted his opinion.[5] Before his death, he reportedly said "Since the Holy Land cannot be a 'physical center' except for very few of our Jewish brethren, it would be far better for us to divide the work of national revival into two, with Palestine as our national (spiritual) center and Argentina as our cultural (physical) center."[5] Nevertheless, Pinsker became one of the founders and a chairman of the Hovevei Zion movement. As part of the movement, he focused on supporting settlements that already existed and helping them to achieve self-sufficiency before organizing any further migration and the establishment of new settlements. Younger activists, such as Menachem Mendel Ussishkin, actively opposed this approach, urging an acceleration of the pace of settlement. [6]

Zionist agricultural settlement

editIn 1890, the Russian authorities approved the establishment of the Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Palestine,[7] dedicated to the practical aspects of establishing Jewish agricultural colonies there. Pinsker headed this charity organization, known as the Odessa Committee. Disagreements between various Jewish religious and secular factions, an internal movement crisis and the ban by the Ottoman Empire on Jewish immigration in the 1890s caused Pinsker to doubt whether Eretz Israel would ever become the solution.

Death and legacy

editPinsker died in Odessa in 1891. His remains were brought to Jerusalem in 1934 and reburied in Nicanor's Cave next to Mount Scopus. Moshav Nahalat Yehuda, now a neighborhood in Rishon LeZion, is named after him, as well as a street in Tel Aviv and several other locales in Israel.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ The Jewish Question: Biography of a World Problem, Alex Bein

- ^ Battenberg, Friedrich (2000). Das europäischen Zeitalter der Juden. Bd.2: Von 1650 bis 1945. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt.

- ^ Battegay, Lubrich, Caspar, Naomi (2018). Jewish Switzerland: 50 Objects Tell Their Stories (in German and English). Basel: Christoph Merian. pp. 126–129. ISBN 9783856168476.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leon Pinsker (1906). Auto-Emancipation. Translated by D. S. Blondheim. The Macabaean Publishing Company.

- ^ a b Gur Alroey (2011). "'Zionism without Zion'? Territorialist Ideology and the Zionist Movement, 1882–1956". Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society. New Series. 18 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2979/jewisocistud.18.1.1.

- ^ Schimmel, Aaron (1 May 2023). "Herzl before Herzl". Mosaic Magazine. Retrieved 4 Nov 2024.

- ^ The Hovevei Zion in Russia-The Odessa committee 1889-1890