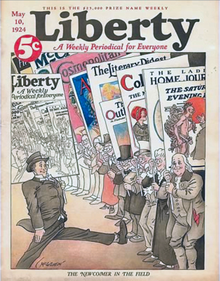

Liberty was an American weekly general-interest magazine, originally priced at five cents and subtitled, "A Weekly for Everybody." It was launched in 1924 by McCormick-Patterson, the publisher until 1931, when it was taken over by Bernarr Macfadden until 1941. At one time it was said to be "the second greatest magazine in America," ranking behind The Saturday Evening Post in circulation.[citation needed] It featured contributions from some of the biggest politicians, celebrities, authors, and artists of the 20th century. The contents of the magazine provided a unique look into popular culture, politics, and world events through the Roaring Twenties, Great Depression, World War II, and postwar America. It ceased publication in 1950 and was revived briefly in 1971.

First issue | |

| Executive Editor | John Neville Wheeler |

|---|---|

| Cartoon Editor | Lawrence Lariar |

| Former editors | Fulton Oursler (1931–1941) Darrell Huff (1941–1946) |

| Staff writers | Robert Benchley Rob Wagner |

| Categories | General-interest |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Publisher | McCormick-Patterson (1924–1931) Bernarr Macfadden (1931–1941) John Cuneo (1941–1944) Paul Hunter (1944) |

| Founder | Robert R. McCormick and Joseph Medill Patterson |

| First issue | May 10, 1924 |

| Final issue | 1950 |

| Company | Kimberly-Clark (1941–1944) |

| Country | U.S. |

| Based in | New York City |

History

editLiberty Magazine was founded in 1924[1] by cousins Colonel Robert Rutherford McCormick and Captain Joseph Medill Patterson, owners and editors of the Chicago Tribune and New York Daily News respectively. In 1924, the owners held a nationwide contest to name the magazine offering $20,000 ($360,000 in current dollar terms) to the winning entry. Among tens of thousands of entries, Charles L. Well won with his title Liberty "A Weekly for Everybody."[2]

The publication constantly lost money under the family duo, though achieving high circulation. It is believed to have lost McCormick and Patterson as much as $12 million over the course of their ownership, and as a result, it was sold to Bernarr MacFadden in 1931.

Under MacFadden's early leadership, the magazine was a strong proponent of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and an article proclaiming him to be physically fit to hold office may have held substantial sway in the outcome of the election. MacFadden led the magazine to considerable success, until it was discovered in 1941 that he had been falsifying circulation reports by as many as 20,000 copies to increase advertising revenue. John Cuneo and Kimberly-Clark Paper company took over for MacFadden in 1941 and righted the indiscretions, but ad revenues never recovered.

In 1926 and 1927, Liberty published the last six Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, including "The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place,” the last of the 60 stories.

The 1944 film noir classic Double Indemnity was based on a novel that was serialized over eight issues of Liberty. The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain was also serialized in Liberty.

Following the lead of The Saturday Evening Post, in 1942 Liberty increased its cover price from five to ten cents, resulting in a drop in sales, down to 1.4 million, and in advertising dollars. In 1944, the magazine was passed on to Paul Hunter, and until its final publication in 1950,[3] a number of different owners tried to revive its former popularity, to no avail.[4] A Canadian edition was published under a series of different ownerships, among them sports entrepreneur Jack Kent Cooke, through the mid-1960s.

In 1968, Dr. Seuss sued Liberty over a copyright dispute regarding cartoons he had sold to the magazine in 1932. Unlike most publications at the time, Liberty typically bought not only first serial rights, but all publishing and distribution rights to the work of their contributors. Liberty won the case, and their copyrights were solidly established by a landmark ruling in copyright law.[citation needed]

Editors

editThe first editor was John Neville Wheeler: in 1924, he became executive editor of Liberty and served in that capacity until early 1926 while continuing to run the Bell Syndicate.

Other editors included Fulton Oursler, in the Macfadden years, and Darrell Huff.

Two prominent editors in the fiction department died a month apart in 1939. Elliot Balestier, Rudyard Kipling's brother-in-law, was an associate editor from the magazine's founding through his death on October 17, 1939.[5] Oscar Graeve, former editor of The Delineator, died in the Liberty offices on November 20, 1939.[6]

Beginning in 1942, the cartoon editor was Lawrence Lariar, who started The Thropp Family, the first comic strip to run as a continuity in a national magazine.[7]

Contributors

editLiberty carried work by many of the most important and influential writers of the period. As a general interest magazine, it featured content across a broad range of genres including adventure, mystery and suspense, western, biographies and autobiographies, love, war, humor, and a whole host of opinion and interest articles.[8] Unusual for a magazine of the era, they bought the rights to many of the printed works outright, and these remain in the hands of the Liberty Library Corporation.

Authors

editThe magazine featured works of fiction from literary giants whose legacy is still strongly felt today. Examples of some of Liberty's most well known authors include F. Scott Fitzgerald, P. G. Wodehouse, Dashiell Hammett, George Bernard Shaw, Agatha Christie, H. L. Mencken, Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Benchley, Paul Gallico, Irvin S. Cobb, John Galsworthy, MacKinlay Kantor, F. Hugh Herbert, J. P. McEvoy, H. G. Wells, and Louis Bromfield.[9]

Celebrities

editAs a general interest magazine for the masses, Liberty frequently had opinion pieces by the biggest names in sports and entertainment of the day, many of whom remain iconic in American culture. Featured in Liberty's pages are articles by Frank Sinatra, Harry Houdini, Groucho Marx,[10] Shirley Temple, Mae West, Jack Dempsey, W.C. Fields, Mary Pickford, Greta Garbo, Al Capone, Babe Ruth, Mickey Rooney, Jean Harlow, and Joe DiMaggio.[11]

Statesmen and historical figures

editPerhaps giving Liberty its greatest historical significance and value is its contributions by some of the most influential world leaders and historical figures, including Mahatma Gandhi, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Benito Mussolini, Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky, and Amelia Earhart.[12] The articles written by these figures provide insight into the minds of those who changed history, supplemented by a large quantity of articles written about these figures.

Illustrators

editLiberty's image library consists of 1,300 full-color covers, 12,000 article illustrations, and 15,000 cartoons from a combined 818 artists. Some of the greatest artists and cartoonists of the 20th Century contributed images to Liberty. Included within the magazine's pages are James Montgomery Flagg (of "Uncle Sam Wants You" fame), Walt Disney, Dr. Seuss, Leslie Thrasher, John Held Jr., Peter Arno, McClelland Barclay, Robert W. Edgren, Neysa McMein, Arthur William Brown, Emmett Watson, Wallace Morgan, Ralph Barton, W. T. Benda, John T. McCutcheon, Willy Pogany, Harold Anderson, and many more.[13]

Reading time

editA memorable feature was the "reading time," provided on the first page of each article so readers could know how long it should take to read an article, such as "No More Glitter: A Searching Tale of Hollywood and a Woman's Heart," Reading Time: 18 minutes, 45 seconds." This was calculated by a member of the editorial staff who would carefully time himself while reading an article at his usual pace; then he would take that time and double it.[14]

in 2003, columnist and writing instructor Roy Peter Clark calculated the reading time of the February 10, 1940, issue:

- I tested Liberty's calculation by timing my reading of two short pieces, a fictional story and an analysis of national politics. The first one promised me I could read it in 5 minutes, 25 seconds. (It took me 4 minutes and 40 seconds.) Reading Time for the next was 5 minutes and 35 seconds. (For me, 4 minutes, 50 seconds.) I'm not the fastest reader in the world, but I do have practice and education on my side, which leads me to the conclusion that the magazine got the average reading time about right. Now there is a difference between Clock Time and Experience Time. We say that "Time dragged," or that it "Flew by." Some stories read so well that they trap us in Story Time ("I couldn't put it down"). Others forces us to slog through dense verbiage, an experience where seconds can seem like minutes... In the 58 pages of Liberty magazine, there were 15 features marked by Approximate Reading Time. Rounded off to minutes, here they are in order: 21, 19, 14, 5, 17, 7, 4, 12, 5, 28, 7, 15, 8, 9, 7. I'll do the math: 178 minutes. That's two minutes shy of three hours. That doesn’t count the time it would take to read the ads, the movie reviews, and do the crossword puzzle. Liberty magazine existed in a world without television and the Internet. Time pressures on readers and potential readers change with the times.[15]

Cultural references

editOver 120 full-feature films and television shows have been produced from content within Liberty, including Mister Ed The Talking Horse, Double Indemnity, and Sergeant York.

In the Marx Brothers comedy The Cocoanuts, Groucho Marx exhorts his hotel employees, "Remember, there's nothing like liberty—except Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post!"

In her working notes for The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand mentioned the character Peter Keating as "the kind of person who occasionally reads Liberty magazine",[16] though this reference did not enter the final version of the book. As Rand depicted Keating as a despicable, shallow opportunist and hypocrite, this was no recommendation for the magazine.

In "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty", author James Thurber makes a reference to the magazine.

In the Alvino Rey song, "I Said No," the female singer teasingly turns down her male caller with a songful of rejections: "I said no, no, no". The song's twist ending is that she is actually saying "no" to a Liberty subscription.[citation needed]

The publication of a poem in the magazine forms part of a sub-plot in "The Chicken Thief", an episode in the second series of The Waltons television series.

Toni Morrison also makes reference to it Liberty The Bluest Eye (1970) when describing the nameless woman from Mobile.

1970s revival as The Nostalgia Magazine

edit| Former editors | James Palmer |

|---|---|

| Categories | Nostalgia |

| Frequency | Quarterly |

| Founder | Robert Whiteman |

| First issue | Summer 1971 |

| Final issue | Fall 1976 |

| Company | Liberty Library Corporation and Twenty First Century Communications, Inc. |

| Country | U.S. |

| Based in | New York City |

In 1969, Robert Whiteman, who as a youngster sold the magazine door-to-door, partnered with Irving Green to purchase the Liberty Library Corporation, holder of the many rights of Liberty magazine.[17] Shortly after, in 1971, in partnership with Twenty First Century Communications, Inc., Liberty was revived as a quarterly nostalgia-oriented magazine.

Liberty: The Nostalgia Magazine was originally dedicated solely to reprinting material from the original Liberty, with each issue having a theme. The "Crime" issue featured vintage reports about John Dillinger, Bruno Hauptmann, J. Edgar Hoover, and other newsworthy personalities of the 1920s and '30s. The "Funny Men" issue was devoted to famous comedians (Laurel and Hardy, Burns and Allen, Milton Berle, Charlie Chaplin, etc.). Each issue featured reprints of a humorous essay by Robert Benchley and vintage film reviews by Rob Wagner and other former staff columnists.

The compilation-of-archival-material format ran for only eight issues, when Whiteman and Green's Liberty Library Corporation fully took over publication.[18] The Summer 1973 issue, under new editor James Palmer, was themed "The Sex Gods and Goddesses of Hollywood," in the wake of Burt Reynolds posing naked in the April 1972 issue of Cosmopolitan.[19] Palmer wrote: "There's no doubt about it, it's the bad girls and guys who stir our imagination. And the more they can shock us (in this supposedly shockproof age) the better... Therefore, we've decided to change the format of Liberty from all nostalgia to Liberty Then and Now."[20] Palmer offered his own take on the Burt Reynolds affair by publishing a nude centerfold of a W. C. Fields look-alike. Readers were outraged by the radical change in focus, and Palmer's tenure as editor ended after two issues. He was replaced by a rotating succession of editors, who modified the "then and now" approach by reinstating the vintage material but contrasting it with new overviews (a look at vintage comic strips, a retrospective about "old movies," etc.). A special "50th Anniversary" issue, consisting largely of archival material, was published in 1974. The new Liberty ended with the Fall 1976 issue.

The complete run of the 1970s version was briefly available online via Google Book Search. Liberty Library Corporation, which still owns the rights to the Liberty archives, stated at the time that Google would also eventually digitize the 1,387 issues that comprised the original magazine's run.[21] As of 2014, collections of Liberty articles were available via the Amazon Kindle store.)

Liberty Library Corporation now offers a similar online feature called "The Watchlist"[22] which features early stories linked to current news headlines. A recent pairing, for example, was a 2009 headline about New York Yankees player salaries and a 1938 article by Joe DiMaggio titled "How Much Is a Ball Player Worth?"[23]

In 2014, glendonTodd Capital acquired a controlling share of Liberty Library Corporation.[24] The company hoped to revive the brand and reinvigorate the content after its 40-year dormancy.

References

edit- ^ Daniel Niemeyer (December 2012). 1950s American Style: A Reference Guide (hard cover). Lulu.com. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-304-54574-9. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Liberty: The Stories Never Die". Liberty Magazine. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Philip Nel (January 2005). Dr. Seuss: American Icon. A&C Black. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8264-1708-4. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "A short history of Liberty Magazine with an examination of issues from 1935". Collecting Old Magazines. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Boston Herald, October 19, 1939.

- ^ Richmond Times Dispatch, November 21, 1939.

- ^ Rochelle, Ogden J. "How Busy Can Man Get?" Editor & Publisher, March 19, 1949.

- ^ "Liberty Magazine: The Stories Never Die". Liberty Magazine. Liberty Library Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Liberty Magazine Historical Archive, 1924-1950". Gale Digital Collections. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Inside the Icons". Liberty Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Liberty Magazine Historical Archive, 1924-1950". Gale Digital Collections. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Liberty Magazine Historical Archive, 1924-1950". Gale Digital Collections. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "The Art of Liberty". Liberty Magazine. Liberty Library Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Liberty Magazine". Retro Galaxy. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ^ "Clark, Roy Peter. "An Idea Whose Time Has Come", Poynter Online, October 10, 2003". Poynter.org. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ^ Journals of Ayn Rand, 12 February 1936.

- ^ "About Liberty Magazine". Liberty Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ Cail, Dave "Lostboy". "- History - (up to 2023): National Lampoon". Heavy Metal Magazine Fan Page.

- ^ "Burt Reynolds changed the way we thought about sex — by getting naked on a bearskin rug". The Washington Post. September 7, 2018.

- ^ Palmer, James (Summer 1973). "The New Look of Liberty". Liberty Then and Now. p. 8.

- ^ Liberty 1971-76. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Budd Shulberg. "The Watchlist". Liberty Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ DiMaggio, Joe (June 18, 1938). "How Much Is a Ball Player Worth". Liberty Magazine. Archived from the original on 2010-02-08.

- ^ "Dallas-based startup The Liberty Project to launch June 24, 2015". StartupBeat. May 21, 2015.

Further reading

edit- Churchill, Allen (1969). The Liberty Years, 1924-1950. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-535807-8. OCLC 645075589 – via Internet Archive.

External links

edit- Official website

- "Liberty Magazine Historical Archive, 1924-1950". Gale.

- "Liberty Magazine". RetroGalaxy.com. Archived from the original on 2005-12-15.

- "Liberty, A Weekly for Everybody". magazineart.org: A visual encyclopedia of American magazine art 1870-1940. Archived from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2023-01-14.