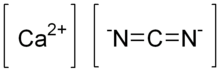

Calcium cyanamide, also known as Calcium carbondiamide, Calcium cyan-2°-amide or Calcium cyanonitride is the inorganic compound with the formula CaCN2. It is the calcium salt of the cyanamide (CN2−

2) anion. This chemical is used as fertilizer[3] and is commercially known as nitrolime. It also has herbicidal activity and in the 1950s was marketed as cyanamid.[4][5] It was first synthesized in 1898 by Adolph Frank and Nikodem Caro (Frank–Caro process).[6]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Calcium cyanamide

| |

| Other names

Cyanamide calcium salt, Calcium carbondiamide, Lime Nitrogen, UN 1403, Nitrolime

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.330 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1403 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CaCN2 | |

| Molar mass | 80.102 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid (Often gray or black from impurities) |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 2.29 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 1,340 °C (2,440 °F; 1,610 K)[1] |

| Boiling point | 1,150 to 1,200 °C (2,100 to 2,190 °F; 1,420 to 1,470 K) (sublimes) |

| Reacts | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H318, H335 | |

| P231+P232, P261, P280, P305+P351+P338 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

none[2] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[2] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 1639 |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Cyanamide Calcium carbide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

History

editIn their search for a new process for producing cyanides for cyanide leaching of gold, Frank and Caro discovered the ability of alkaline earth carbides to absorb atmospheric nitrogen at high temperatures.[7] Fritz Rothe, a colleague of Frank and Caro, succeeded in 1898 in overcoming problems with the use of calcium carbide and clarified that at around 1,100 °C not calcium cyanide but calcium cyanamide is formed in the reaction. In fact, the initial target product sodium cyanide can also be obtained from calcium cyanamide by melting it with sodium chloride in the presence of carbon:[8]

- CaCN2 + 2 NaCl + C → 2 NaCN + CaCl2

Frank and Caro developed this reaction for a large-scale, continuous production process. It was particularly challenging to implement because it requires precise control of high temperatures during the initial igniter step; the melting point of calcium cyanamide is only about 120°C lower than the boiling point of sodium chloride.

In 1901, Ferdinand Eduard Polzeniusz patented a process that converts calcium carbide to calcium cyanamide in the presence of 10% calcium chloride at 700 °C. The advantage of this reaction temperature (lower by about 400 °C), however, must be weighed against the large amount of calcium chloride required and the discontinuous process control. Nevertheless, both processes (the Rothe–Frank–Caro process and the Polzeniusz–Krauss process) played a role in the first half of the 20th century. In the record year 1945, a total of approximately 1.5 million tonnes was produced worldwide using both processes.[9] Frank and Caro also noted the formation of ammonia from calcium cyanamide.[10]

- CaCN2 + 3 H2O → 2 NH3 + CaCO3

Albert Frank recognized the fundamental importance of this reaction as a breakthrough in the provision of ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen and in 1901 recommended calcium cyanamide as a nitrogen fertilizer. Between 1908 and 1919, five calcium cyanamide plants with a total capacity of 500,000 tonnes per year were set up in Germany, and one in Switzerland.[11] It was at the time the cheapest nitrogen fertilizer with additional efficacy against weeds and plant pests, and had great advantages over the nitrogen fertilizers that were conventional at the time. However, the large-scale implementation of ammonia synthesis via the Haber process became a serious competitor to the very energy-intensive Frank–Caro process. As urea (formed via the Haber–Bosch process) was significantly more nitrogen-rich (46% nitrogen compared to ca. 20%), cheaper, and faster acting, the role of calcium cyanamide was gradually reduced to a multifunctional nitrogen fertilizer for niche applications. Other reasons for its loss of popularity were its dirty-black color, dusty appearance and irritating properties, as well as its inhibition of an alcohol-degrading enzyme which causes temporary accumulation of acetaldehyde in the body leading to dizziness, nausea, and alcohol flush reaction when alcohol is consumed around the time of bodily exposure.

Production

editCalcium cyanamide is prepared from calcium carbide. The carbide powder is heated at about 1000 °C in an electric furnace into which nitrogen is passed for several hours.[12] The product is cooled to ambient temperatures and any unreacted carbide is leached out cautiously with water.

- CaC2 + N2 → CaCN2 + C (ΔH

o

f = –69.0 kcal/mol at 25 °C)

It crystallizes in hexagonal crystal system with space group R3m and lattice constants a = 3.67 Å, c = 14.85 Å.[13][14]

Uses

editThe main use of calcium cyanamide is in agriculture as a fertilizer.[3] In contact with water, it hydrolyses into hydrogen cyanamide which decomposes and liberates ammonia:[5]

- CaCN2 + 3 H2O → 2 NH3 + CaCO3

It was used to produce sodium cyanide by fusing with sodium carbonate:

- CaCN2 + Na2CO3 + 2 C → 2 NaCN + CaO + 2 CO

Sodium cyanide is used in cyanide process in gold mining. It can also be used in the preparation of calcium cyanide and melamine.

Through hydrolysis in the presence of carbon dioxide, calcium cyanamide produces cyanamide:[clarification needed]

- CaCN2 + H2O + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2NCN

The conversion is conducted in slurries. For this reason, most commercial calcium cyanamide is sold as an aqueous solution.

Thiourea can be produced by the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with calcium cyanamide in the presence of carbon dioxide.[15]

Calcium cyanamide is also used as a wire-fed alloy in steelmaking to introduce nitrogen into the steel.

Safety

editThe substance can cause alcohol intolerance, before or after the consumption of alcohol.[5]

References

edit- ^ Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- ^ a b NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0091". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b Auchmoody, L.R.; Wendel, G.W. (1973). "Effect of calcium cyanamide on growth and nutrition of plan fed yellow-poplar seedlings". Res. Pap. Ne-265. Uppdr Darby, Pa: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station. 11 P. 265. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Carr, Charles W. (1953). The use of cyanamid for weed control in vegetable crops (MSc thesis). University of Massachusetts Amherst. doi:10.7275/18863820.

- ^ a b c Potential risks to human health and the environment from the use of calcium cyanamide as fertiliser, Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks, 1,534 kB, March 2016, Retrieved 22 July 2017

- ^ "History of Degussa: Rich harvest, healthy environment: Calcium cyanamide". Archived from the original on 2006-10-19. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Deutsches Reichspatent DRP 88363, "Verfahren zur Darstellung von Cyanverbindungen aus Carbiden", Erfinder: A. Frank, N. Caro, erteilt am 31. März 1895.

- ^ H.H. Franck, W. Burg, Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie und angewandte physikalische Chemie, 40(10), 686-692 (Oktober 1934).

- ^ "Commercialization of Calcium Carbide and Acetylene - Landmark". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ^ Angewandte Chemie, Band 29, Ausgabe 16, Seite R97, 25. Februar 1916

- ^ Eschenmooser, Walter (June 1997). "100 Years of Progress with LONZA". CHIMIA. 51 (6): 259-269. doi:10.2533/chimia.1997.259. S2CID 100485418.

- ^ Thomas Güthner; Bernd Mertschenk (2006). "Cyanamides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_139.pub2. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ F. Brezina, J. Mollin, R. Pastorek, Z. Sindelar. Chemicke tabulky anorganickych sloucenin (Chemical tables of inorganic compounds). SNTL, 1986.

- ^ Vannerberg, N.G. "The crystal structure of calcium cyanamide" Acta Chemica Scandinavica (1-27,1973-42,1988) (1962) 16, p2263-p2266

- ^ Mertschenk, Bernd; Beck, Ferdinand; Bauer, Wolfgang (2000). "Thiourea and Thiourea Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a26_803.pub3. ISBN 978-3527306732.

External links

edit- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0091". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Bioassay of Calcium Cyanamide for Possible Carcinogenicity (CAS No. 156-62-7)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 679.