Lincoln is a city in Logan County, Illinois, United States. First settled in the 1830s, it is the only town in the U.S. that was named for Abraham Lincoln before he became president; he practiced law there from 1847 to 1859. Lincoln is home to two prisons. It is also the home of the world's largest covered wagon and numerous other historical sites along the Route 66 corridor.

Lincoln, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Logan County Courthouse | |

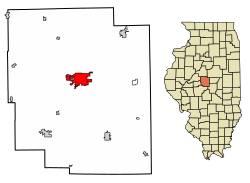

Location of Lincoln in Logan County, Illinois. | |

| Coordinates: 40°09′02″N 89°23′28″W / 40.15056°N 89.39111°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Logan |

| Township | East Lincoln, West Lincoln |

| Government | |

| • Acting Mayor | Tracy L. Welch |

| Area | |

• Total | 6.25 sq mi (16.19 km2) |

| • Land | 6.25 sq mi (16.18 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 589 ft (180 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 13,288 |

| • Density | 2,127.10/sq mi (821.28/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 62656 |

| Area code | 217 |

| FIPS code | 17-43536 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2395710[1] |

| Wikimedia Commons | Lincoln, Illinois |

| Website | http://www.lincolnil.gov/ |

The population was 13,288 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Logan County.[3]

History

editThe town's standard history holds that it was officially named on August 27, 1853, in an unusual ceremony. Abraham Lincoln, having assisted with the platting of the town and working as counsel for the newly laid Chicago & Mississippi Railroad which led to its founding, was asked to participate in a naming ceremony for the town. On this date, the first sale of lots took place in the new town. Ninety were sold at prices ranging from $40 to $150. According to tradition Lincoln was present. At noon he purchased two watermelons and carried one under each arm to the public square. There he invited Latham, Hickox, and Gillette, proprietors, to join him, saying, "Now we'll christen the new town," squeezing watermelon juice out on the ground.[4] Legend has it that when it had been proposed to him that the town be named for him, he had advised against it, saying that in his experience, "Nothing bearing the name of Lincoln ever amounted to much." The town of Lincoln was the first city named after Abraham Lincoln, while he was a lawyer and before he was President of the United States.[5][6]

Despite that story, newspaper reports make it clear that the city's name of Lincoln had been chosen at least several weeks before the August 27 date.[7][8][9] The new site of Lincoln was about three-quarters of a mile from the small settlement of Postville.[10] "The position is fine and commanding, and if it does not make a big city, we have no doubt it will soon arrive at the dignity of a flourishing and respectable town," the Illinois State Register wrote. "We will also add that the town was named by the proprietors, of whom our enterprising citizen, Virgil Hickox, is one, in honor of A. Lincoln, esq., the attorney of the Chicago and Mississippi Railroad Company."[10]

Lincoln College (chartered Lincoln University), a private four-year liberal arts college, was founded in early 1865 and granted 2 year degrees until 1929. News of the establishment and name of the school was communicated to President Lincoln shortly before his death, making Lincoln the only college to be named after Lincoln while he was living. Despite the city of Lincoln's 90%+ white population, Lincoln college was an HBCU. After a cyber attack in 2021, Lincoln College closed permanently in May 2022.[11] The College had an excellent collection of Abraham Lincoln–related documents and artifacts, housed in a museum which was open to the general public before their closure.

The City of Lincoln was located directly on U.S. Route 66 from 1926[12] through 1978. This is its secondary tourist theme after the connection with Abraham Lincoln. The Lincoln City Hall was built in 1895. A phone booth was installed on the roof of the building in the 1960s for weather spotting.[13]

American author Langston Hughes spent one year of his youth in Lincoln.[14] Later on, he was to write to his eighth-grade teacher in Lincoln, telling her his writing career began there in the eighth grade, when he was elected class poet.

American theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Helmut Richard Niebuhr lived in Lincoln from 1902 through their college years. Reinhold Niebuhr first served as pastor of a church when he served as interim minister of Lincoln's St. John's German Evangelical Synod church following his father's death.[15] Reinhold Niebuhr is best known as the author of the Serenity Prayer.

The City of Lincoln features the stone, three-story, domed Logan County Courthouse (1905). This courthouse building replaced the earlier Logan County Courthouse (built 1858) where Lincoln once practiced law; the earlier building had fallen into serious decay and could not be saved. In addition, the Postville Courthouse State Historic Site contains a 1953 replica of the original 1840 Logan County courthouse; Postville, the original county seat, lost its status in 1848 and was itself annexed into Lincoln in the 1860s.[16]

Lincoln was also the site of the Lincoln Developmental Center (LDC); a state institution for the developmentally disabled. Founded in 1877, the institution was one of Logan County's largest employers[17] until closed in 2002 by then-Governor George Ryan due to concerns about patient maltreatment. Despite efforts by some Illinois state legislators to reopen LDC, the facility remains shuttered.[18][19][20][21]

Geography

editAccording to the 2010 census, Lincoln has a total area of 6.4 square miles (16.58 km2), all land.[22]

I-55 (formerly U.S. Route 66) connects Lincoln to Bloomington and Springfield. Illinois Route 10 and Illinois Route 121 run into the city. Amtrak serves Lincoln Station daily with its Lincoln Service and Texas Eagle routes. Service consists of four Lincoln Service round-trips between Chicago and St. Louis, and one Texas Eagle round-trip between San Antonio and Chicago. Three days a week, the Eagle continues on to Los Angeles.[23][24] Lines of the Union Pacific and Canadian National railroads run through the city. Salt Creek (Sangamon River Tributary) and the Edward R. Madigan State Fish and Wildlife Area are nearby.

Climate

editLincoln has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa). Monthly means range from 26.1 °F (−3.3 °C) in January to 74.6 °F (23.7 °C) in July.[25] There are 126 days below freezing while there are 24 days above 90 °F (32 °C).[25] Since having an average record minimum of −11 °F (−24 °C) (-24 °C) according to XMACIS,[26] It lies in the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 5b.

The highest temperature was 113 °F (45 °C) on July 15, 1936, and the lowest was −34 °F (−37 °C) on January 15, 1927.[27]

| Climate data for Lincoln, IL (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1906–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

75 (24) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

102 (39) |

105 (41) |

113 (45) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

95 (35) |

83 (28) |

72 (22) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

62 (17) |

74 (23) |

83 (28) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

94 (34) |

92 (33) |

85 (29) |

72 (22) |

61 (16) |

96 (36) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.5 (1.4) |

39.5 (4.2) |

51.7 (10.9) |

64.4 (18.0) |

74.8 (23.8) |

83.3 (28.5) |

85.5 (29.7) |

84.0 (28.9) |

79.2 (26.2) |

66.3 (19.1) |

51.4 (10.8) |

39.2 (4.0) |

62.8 (17.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.1 (−3.3) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

41.4 (5.2) |

52.6 (11.4) |

63.6 (17.6) |

72.3 (22.4) |

74.6 (23.7) |

72.6 (22.6) |

66.3 (19.1) |

54.1 (12.3) |

41.7 (5.4) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

52.2 (11.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 17.8 (−7.9) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

40.8 (4.9) |

52.4 (11.3) |

61.3 (16.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

61.3 (16.3) |

53.4 (11.9) |

41.8 (5.4) |

32.0 (0.0) |

23.1 (−4.9) |

41.7 (5.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

1 (−17) |

12 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

49 (9) |

53 (12) |

51 (11) |

38 (3) |

26 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

3 (−16) |

−10 (−23) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −34 (−37) |

−23 (−31) |

−14 (−26) |

−1 (−18) |

24 (−4) |

35 (2) |

41 (5) |

36 (2) |

22 (−6) |

7 (−14) |

−3 (−19) |

−29 (−34) |

−34 (−37) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.17 (55) |

1.92 (49) |

2.70 (69) |

4.24 (108) |

4.37 (111) |

4.16 (106) |

4.91 (125) |

3.47 (88) |

3.30 (84) |

3.42 (87) |

2.88 (73) |

2.29 (58) |

39.83 (1,012) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.7 (14) |

6.2 (16) |

1.8 (4.6) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.6 (1.5) |

4.9 (12) |

19.3 (49) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.3 | 8.9 | 10.5 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 10.5 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 8.0 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 117.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.3 | 4.4 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 16.5 |

| Source: NOAA[27][25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 5,639 | — | |

| 1890 | 6,725 | 19.3% | |

| 1900 | 8,962 | 33.3% | |

| 1910 | 10,892 | 21.5% | |

| 1920 | 11,882 | 9.1% | |

| 1930 | 12,855 | 8.2% | |

| 1940 | 12,752 | −0.8% | |

| 1950 | 14,362 | 12.6% | |

| 1960 | 16,890 | 17.6% | |

| 1970 | 17,582 | 4.1% | |

| 1980 | 16,327 | −7.1% | |

| 1990 | 15,418 | −5.6% | |

| 2000 | 15,369 | −0.3% | |

| 2010 | 14,504 | −5.6% | |

| 2020 | 13,288 | −8.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] | |||

According to the 2010 United States Census, Lincoln had 14,504 people. Among non-Hispanics this includes 13,262 White (91.4%), 528 Black (3.6%), 118 Asian (0.8%), and 227 from two or more races. The Hispanic or Latino population included 336 people (2.3%).

There were 5,877 households, out of which 29.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.1% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with children & no husband present, and 40.1% were non-families. 33.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 29.7% had someone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.25 and the average family size was 2.83.

The population was spread out, with 78.5% over the age of 18 and 17.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.0 years. The gender ratio was 47.9% male & 52.1% female. Among 5,877 occupied households, 64.6% were owner-occupied & 35.4% were renter-occupied.

As of the census of 2000, there were 15,369 people, 5,965 households, and 3,692 families residing in the town. The population density was 2,596.6 inhabitants per square mile (1,002.6/km2). There were 6,391 housing units at an average density of 1,079.8 per square mile (416.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.79% White, 2.82% African American, 0.16% Native American, 0.89% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.45% from other races, and 0.86% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.19% of the population.

There were 5,965 households, out of which 28.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.7% were married couples living together, 11.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.1% were non-families. 33.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.89.

The town's population is spread out, with 21.6% under the age of 18, 13.8% from 18 to 24, 26.4% from 25 to 44, 21.5% from 45 to 64, and 16.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $34,435, and the median income for a family was $45,171. Males had a median income of $33,596 versus $22,500 for females. The per-capita income for the town is $17,207. About 8.5% of families and 10.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.9% of those under age 18 and 8.7% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

editThe United States Postal Service operates the Lincoln Post Office.[29]

The Illinois Department of Corrections Logan Correctional Center is located in unincorporated Logan County, near Lincoln.[30]

Cresco Labs opened their cultivation site there and has since replaced over 250 jobs lost when the bottle factory closed down. The farm has shown to be an integral factor in Lincoln’s economy.[citation needed]

Education

editMost of Lincoln is in the Lincoln Elementary School District 27 while parts are in West Lincoln-Broadwell Elementary School District 92 and Chester-East Lincoln Community Consolidated School District 61. All of Lincoln is in Lincoln Community High School District 404.[31]

Notable people

edit- Scott Altman, NASA astronaut and space shuttle Columbia commander

- Brian Cook, forward for five NBA teams

- Henry Darger, writer and artist

- William D. Gayle, Illinois State Representative and Mayor of Lincoln

- Langston Hughes, poet, novelist, playwright

- Terry Kinney, actor, cofounder of the Steppenwolf Theatre Company

- David T. Littler, Illinois state legislator and lawyer

- Edward R. Madigan, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture (1991–1993), congressman (1973–1991)

- Robert Madigan, Illinois State Senator

- William Keepers Maxwell, Jr., author; his 1979 novel So Long, See You Tomorrow is set in Lincoln

- Kelly McEvers, journalist and correspondent for NPR

- Alberta Nichols, composer for Broadway, radio and films of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s[32]

- H. Richard Niebuhr, prominent American theologian, brother of Reinhold Niebuhr

- Reinhold Niebuhr, prominent American theologian and author of Serenity Prayer, brother of H. Richard Niebuhr

- Stella Pevsner, children's book author

- Clifford Quisenberry, Illinois State Representative

- Rip Ragan, MLB pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds

- Dick Reichle, MLB outfielder for the Boston Red Sox

- Bill Sampen, former Major League baseball pitcher

- Kevin Seitzer, former Major League Baseball player

- Tony Semple, former National Football League player

- Willis R. Shaw, Illinois state senator

- John Schlitt, lead singer of Christian rock band Petra

- Larry Tagg, rock musician, songwriter, teacher, and historian

- John Turner Illinois State Representative and judge

- Emil Verban, MLB second baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals, Philadelphia Phillies, Chicago Cubs and Boston Braves

- Dennis Werth, MLB first baseman for the New York Yankees and Kansas City Royals

References

edit- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lincoln, Illinois

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence B. Stringer, ed., History of Logan County, 2 vols. (Chicago: Pioneer Publishing Co., 1911), 1:568-69

- ^ "Lincoln College Museum - Lincoln, Illinois". Mount Pleasant, Iowa: Greg Watson. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Lincoln History". Lincoln, Illinois. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "Railroad Extension to Postville". The Daily Alton Telegraph. August 16, 1853. p. 2. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "By reference to..." Alton Daily Courier. August 18, 1853. p. 2. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "Great Sale of Lots in the Town of Lincoln". Illinois State Register. August 18, 1853. p. 3. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Some of our readers..." Illinois State Register. August 25, 1853. p. 1. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ "They found their home in college. Then it closed forever". Washington Post. November 27, 2022. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ "Introduction to the Railroad Heritage and Route 66 Heritage of Lincoln, Illinois". Findinglincolnillinois.com.

- ^ Hinckley, Jim (2017). Route 66: America's Longest Small Town. Quarto Publishing Group USA. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7603-5753-8.

- ^ "Langston Hughes biography: African-American history: Crossing Boundaries: Kansas Humanities Council". Kansasheritage.org.

- ^ Fox, Richard (1985). Reinhold Niebuhr. San Francisco: Harper & Row. pp. 5 to 24. ISBN 0-06-250343-X.

- ^ "Logan Co. Courthouse History of Lincoln, Illinois". Findinglincolnillinois.com.

- ^ "Layoffs mean more limbo for Lincoln Developmental Center | Local News". Pantagraph.com. August 12, 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Kurt Erickson (March 19, 2010). "Eight years later, closed Lincoln Developmental Center remains in limbo". Herald-Review.com. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "State of Illinois Home - IGNN (Illinois Government News Network)". 3.illinois.gov. Archived from the original on May 7, 2003.

- ^ "State of Illinois Home - IGNN (Illinois Government News Network)". 3.illinois.gov. Archived from the original on September 12, 2003.

- ^ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ "Amtrak Lincoln Service and Missouri River Runner Timetable" (PDF). Amtrak. September 13, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Amtrak Texas Eagle Timetable" (PDF). Amtrak. March 11, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Station: Lincoln, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "XMACIS". XMACIS. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ "Post Office Location - LINCOLN Archived 2012-08-21 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Logan Correctional Center." Illinois Department of Corrections. Retrieved on October 12, 2010. "1096 1350th Street P.O. Box 1000 Lincoln, Il 62656"

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Logan County, IL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2024. - Text list

- ^ American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (1980). ASCAP biographical dictionary of composers, authors and publishers. Bowker. ISBN 978-0-8352-1283-0.

External links

edit- City of Lincoln, Illinois

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.