Lisbon is the county seat of Columbiana County, Ohio, United States.[5] The population was 2,597 at the 2020 census.[6] Lying along the Little Beaver Creek, the village is located 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Youngstown.

Lisbon, Ohio | |

|---|---|

| |

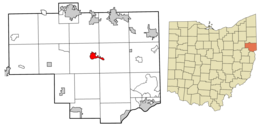

Location of Lisbon in Columbiana County and in the State of Ohio | |

| Coordinates: 40°46′24″N 80°44′53″W / 40.77333°N 80.74806°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Columbiana |

| Founded | 1803 |

| Named for | Lisbon, Portugal |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Peter Wilson (I)[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.68 sq mi (4.36 km2) |

| • Land | 1.68 sq mi (4.36 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,014 ft (309 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 2,597 |

| • Density | 1,542.16/sq mi (595.43/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 44432 |

| Area code(s) | 330, 234 |

| FIPS code | 39-44030[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2398448[3] |

| School District | Lisbon Exempted Village School District |

| Website | http://www.lisbonvillage.com/ |

History

editLisbon was platted on February 16, 1803, by Baptist minister Lewis Kinney, originally named New Lisbon after Lisbon, Portugal.[7] The village was incorporated under a special act of legislature on February 7, 1825.[8]

Initially known for its iron and whiskey production, New Lisbon became an economic hub of many sorts into the Industrial Revolution, and one of the largest towns on the Sandy and Beaver Canal.[9] During this time, the village claimed the county's first bank, the Columbiana Bank of New Lisbon; its first insurance company, and the first Ohio newspaper, The Ohio Patriot, founded by an Alsatian immigrant, William D. Lepper.[10]

Lisbon has the distinction of being the northernmost western town involved in military actions during the American Civil War. Confederate Army general John Hunt Morgan surrendered to New Lisbon militia forces in nearby West Point at the end of Morgan's Raid into Ohio.[11]

After the failure of the canal, the town had to wait until the late 1860s to receive railroad access once the Niles and New Lisbon Railroad opened. It and the later Pittsburgh, Marion & Chicago Railway helped bring industry to the area, including the porcelain manufacturing R. Thomas and Sons Company.[9] The village was renamed Lisbon in 1895.[12]

In 1900, the modern drinking straw was invented and patented in Lisbon.[13][14]

In 1899, Jacob L. Beilhart founded the Spirit Fruit Society, an intentional community to practice his newly developed beliefs, in Lisbon.[15] Its goal was to "teach mankind how to apply the truths taught by Jesus Christ," which included a rejection of jealousy and materialism.[16][15] The commune only attracted about a dozen residents, mostly from outside the area.[15] However, views against marriage and promoting free love were not accepted well in Lisbon, and the group left for Chicago in late 1904.[15][17][16]

Lisbon became a qualified Tree City USA as recognized by the National Arbor Day Foundation in 1981.[18]

Geography

editLisbon is located at 40°46′26″N 80°46′3″W / 40.77389°N 80.76750°W (40.773874, -80.767553).[19]

The following highways pass through Lisbon:

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 1.69 square miles (4.38 km2), all land.[20]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 303 | — | |

| 1820 | 746 | 146.2% | |

| 1830 | 1,129 | 51.3% | |

| 1860 | 1,381 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,569 | 13.6% | |

| 1880 | 2,028 | 29.3% | |

| 1890 | 2,278 | 12.3% | |

| 1900 | 3,330 | 46.2% | |

| 1910 | 3,084 | −7.4% | |

| 1920 | 3,113 | 0.9% | |

| 1930 | 3,405 | 9.4% | |

| 1940 | 3,379 | −0.8% | |

| 1950 | 3,293 | −2.5% | |

| 1960 | 3,579 | 8.7% | |

| 1970 | 3,521 | −1.6% | |

| 1980 | 3,159 | −10.3% | |

| 1990 | 3,037 | −3.9% | |

| 2000 | 2,788 | −8.2% | |

| 2010 | 2,821 | 1.2% | |

| 2020 | 2,597 | −7.9% | |

| source:[21] | |||

2010 census

editAs of the census[22] of 2010, there were 2,821 people, 1,138 households, and 693 families residing in the village. The population density was 1,669.2 inhabitants per square mile (644.5/km2). There were 1,287 housing units at an average density of 761.5 per square mile (294.0/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 97.4% White, 1.1% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 0.2% from other races, and 0.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.2% of the population.

There were 1,138 households, of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.4% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.5% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.1% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 3.00.

The median age in the village was 39.6 years. 23.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.3% were from 25 to 44; 28.1% were from 45 to 64; and 15.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the village was 47.3% male and 52.7% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census[4] of 2000, there were 2,788 people, 1,133 households, and 696 families residing in the village. The population density was 2,521.1 inhabitants per square mile (973.4/km2). There were 1,253 housing units at an average density of 1,133.0 per square mile (437.5/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 97.74% White, 0.90% African American, 0.22% Native American, 0.22% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.29% from other races, and 0.61% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.61% of the population.

There were 1,133 households, out of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.5% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.5% were non-families. 34.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 3.07.

In the village, the population was spread out, with 24.9% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 22.6% from 45 to 64, and 15.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.0 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $27,841, and the median income for a family was $36,707. Males had a median income of $29,271 versus $19,826 for females. The per capita income for the village was $14,097. About 10.1% of families and 14.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.4% of those under the age of 18 and 5.2% of those 65 years or over.

Arts and culture

editLisbon is host to the annual Columbiana County Fair in the summer and the Lisbon Johnny Appleseed Festival in the fall; the pioneer is said to had planted an apple tree nursery in the area in the 1800s.[23] The Dulci-More Festival, a music festival dedicated to the Appalachian dulcimer and other traditional musical instruments, formerly took place over Memorial Day weekend at Camp McKinley, a Boy Scout camp near Lisbon from 1995 to 2019.[24]

Folk band Bon Iver paid tribute to the village in the instrumental song "Lisbon, OH", from their 2011 Grammy Award-winning album Bon Iver, Bon Iver.

The village is home to the public Lepper Library, founded in 1897. The building site on Lincoln Way and a $10,000 grant were donated by Virginia Lepper in memory of her late husband.[25]

In 2020, Lisbon became an official North Country National Scenic Trail Town.

Government

editLisbon operates under a mayor–council government, where there are six council members elected as a legislature in addition to an independently elected mayor who serves as an executive.[1] The current mayor is Peter Wilson (I).[1] Additionally, Lisbon has a Board of Trustees of Public Affairs, a three-member board elected separately from the village council.

Education

editChildren in Lisbon are served by the public Lisbon Exempted Village School District. The current schools in the district are McKinley Elementary School (grades K–5) and David Anderson Junior/Senior High School (grades 6–12). The school's athletic teams are known as the Blue Devils. In 1995, the Lisbon Blue Devils boys football team won the OHSAA Division V State Championship against Mariemont High School, the only such championship in football to be held by a Columbiana County school.[26][27]

The Columbiana County Career and Technical Center is immediately south of city limits.

Media

editLisbon is home to the Morning Journal, a local newspaper serving Columbiana County. The result of multiple mergers, it began printing in 1909.[28]

Notable residents

edit- William W. Armstrong, journalist, 15th Ohio Secretary of State

- George M. Ashford, surveyor, pioneer of Arctic Alaska

- Reasin Beall, U.S. Representative from Ohio's 6th district

- Jacob L. Beilhart, communitarian leader, founder of Spirit Fruit Society

- Lucretia Longshore Blankenburg, suffragist and writer

- William T. H. Brooks, U.S. Army Major General during the American Civil War

- John C. Chaney, U.S. Representative from Indiana's 2nd district

- John Hessin Clarke, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

- Charles D. Coffin, U.S. Representative from Ohio's 17th district

- Larry Csonka, former National Football League fullback[29]

- Katy Easterday, football and basketball player with the Pittsburgh Panthers

- George A. Garretson, U.S. Army Brigadier General

- John M. Gilman, politician who served in the Ohio and Minnesota House of Representatives

- Howard Melville Hanna, businessman

- Mark Hanna, U.S. Senator from Ohio and chairman of the Republican National Committee

- Andrew W. Loomis, U.S. Representative from Ohio's 17th district

- Fighting McCooks, famed officers in the Union Army during the American Civil War

- Daniel McCook, attorney and Union Army major

- George Wythe McCook, 4th Ohio Attorney General, Union Army colonel

- Henry Christopher McCook, clergyman and author, Union Army chaplain

- John James McCook, lawyer and professor, Union Army chaplain

- Robert Latimer McCook, Union Army brigadier general

- Roderick S. McCook, U.S. Navy officer

- Betty McKenna, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League third basewoman

- William McKinley Sr., pioneer of the iron industry in eastern Ohio, father of President William McKinley

- Thayer Melvin, 4th West Virginia Attorney General

- James D. Moffat, 3rd President of Washington & Jefferson College

- William Duane Morgan, newspaper editor and politician

- Stephen Paxson, missionary who started over 1,300 Sunday schools in the American frontier

- Zach Paxson, singer-songwriter

- Robert Walker Tayler, U.S. Representative from Ohio's 18th district

- John Thomson, U.S. Representative from Ohio's 6th, 12th, and 17th districts

- Clement Vallandigham, copperhead leader and U.S. Representative from Ohio's 3rd district

References

edit- ^ a b c "2020 General Election Results for Columbiana County" (PDF). Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lisbon, Ohio

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Lisbon village, Ohio". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Overman, William Daniel (1958). Ohio Town Names. Akron, OH: Atlantic Press. p. 76.

- ^ Mack, Horace (1879). History of Columbiana County, Ohio: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Unigraphic. p. 107.

- ^ a b "Lisbon Village Website". Village of Lisbon. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ Robert E. Cazden (1998). "The German Book Trade In Ohio Before 1848". Ohio History. 84: 57–77.

- ^ Mahoning Valley Civil War Round Table Archived October 18, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McCord, William B. (1905). History of Columbiana County, Ohio and Representative Citizens. Biographical Publishing Company. p. 269.

- ^ ""Sucker" U.S. Patent". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ "Lisbon Village History". Village of Lisbon. Retrieved August 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Fogarty, Robert S.; Grant, H. Roger (Spring 1980). "Free Love in Ohio: Jacob Beilhart and the Spirit Fruit Colony". Ohio History. 89 (2): 206–21. PMID 11617838. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Murphy, James L. (1989). The Reluctant Radicals. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-7423-9.

- ^ Murphy, James L. (July 1979). "Jacob Beilhart and the Spirit Fruit Society". Echoes. 18 (7): 1, 3. hdl:1811/38882. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ "Tree Cities Ohio" [1]. Arbor Day Foundation. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. No. XLIII. 1871. pp. 830–831. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.. Full text of "Johnny Appleseed: a pioneer hero" at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Dulci-More Festival 14". billschillingmusic.googlepages.com. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ "About Us". Lepper Library. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Yappi. "Yappi Sports Football". Archived from the original on January 13, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ OHSAA. "Ohio High School Athletic Association". Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ "Ogden Newspapers to Acquire Lisbon (OH) Morning Journal". Dirks, Van Essen & April. December 2, 2003. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ Reiner, Michael (February 8, 2024). "Former NFL player with Lisbon connection to help present Super Bowl trophy". WKBN-TV. Retrieved February 8, 2024.