The List of National Historic Landmarks in Montana contains the landmarks designated by the U.S. Federal Government for the U.S. state of Montana. There are 28 National Historic Landmarks (NHLs) in Montana.

The United States National Historic Landmark program is operated under the auspices of the National Park Service, and recognizes structures, districts, objects, and similar resources nationwide according to a list of criteria of national significance.[1] The Montana landmarks emphasize its frontier heritage, the passage of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Montana's contributions to the national park movement, and other themes.

Three sites in Montana extend across the Idaho or North Dakota state line, and are listed by the National Park Service as Idaho NHLs or North Dakota NHLs.

| [2] | Landmark name | Image | Date designated[3] | Location | County | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bannack Historic District |  |

July 4, 1961 (#66000426) |

Bannack 45°09′40″N 112°59′44″W / 45.1611°N 112.9956°W | Beaverhead | Site of Montana's first major gold discovery in 1862, and served as the capital of Montana Territory briefly.[1] |

| 2 | Butte–Anaconda Historic District |  |

July 4, 1961 (#66000438) |

Butte 46°00′59″N 112°32′10″W / 46.01646°N 112.5361°W | Deer Lodge and Silver Bow | One of the largest and most famous boomtowns in the American West; the district includes more than 6,000 contributing properties.[4] |

| 3 | Camp Disappointment |  |

May 23, 1966 (#66000434) |

Browning 48°35′57″N 112°47′53″W / 48.599167°N 112.798056°W | Glacier | Lewis and Clark Expedition site.[5] |

| 4 | Chief Joseph Battleground of Bear's Paw |  |

June 7, 1988 (#70000355) |

Chinook 48°22′39″N 109°12′34″W / 48.3775°N 109.20944°W | Blaine | Site of the final engagement of the Nez Perce War.[6] |

| 5 | Chief Plenty Coups (Alek-Chea-Ahoosh) Home |  |

January 20, 1999 (#70000354) |

Pryor 45°25′35″N 108°32′54″W / 45.426389°N 108.54833°W | Big Horn | The 2-story house of Crow Nation chief Plenty Coups during 1884-1932, plus a log store and the Plenty Coups Spring.[7] |

| 6 | Deer Medicine Rocks |  |

March 2, 2012 (#12000244) |

near Lame Deer | Rosebud | |

| 7 | First Peoples Buffalo Jump |  |

July 21, 2015 (#15000623) |

Ulm 47°28′46″N 111°31′27″W / 47.47946°N 111.52427°W | Cascade | Believed to be the largest buffalo jump in North America, and maybe the world; possibly the most-utilized on the continent as well |

| 8 | Fort Benton Historic District |  |

November 5, 1961 (#66000431) |

Fort Benton 47°49′10″N 110°40′11″W / 47.819444°N 110.6697°W | Chouteau | Established as a fur trading center in 1847, the fort prospered with the growth of steamboat traffic starting in 1859 and an 1862 gold strike, but declined with the advent of the railroad.[8] |

| 9 | Fort Union Trading Post |  |

July 4, 1961 (#66000103) |

Williston, North Dakota 47°59′58″N 104°02′26″W / 47.999444°N 104.040556°W | Richland County, North Dakota and Roosevelt County, Montana | Most important fur trading post on the upper Missouri until 1867. Visitors included John James Audubon, George Catlin, Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, Sitting Bull, Karl Bodmer, and Jim Bridger. |

| 10 | Going-to-the-Sun Road |  |

February 18, 1997 (#83001070) |

Glacier National Park 48°44′00″N 113°46′00″W / 48.7333°N 113.76667°W | Flathead and Glacier | Main parkway through the heart of Glacier National Park.[2] |

| 11 | Grant-Kohrs Ranch |  |

December 19, 1960 (#72000738) |

Deer Lodge 46°24′30″N 112°44′22″W / 46.40833°N 112.73944°W | Powell | John Grant, the original owner of the ranch, from 1853, is sometimes credited with founding the range-cattle industry in Montana. Conrad Kohrs, who bought the ranch c.1866, was among the foremost "cattle kings" of his era.[9] |

| 12 | Great Falls Portage |  |

May 23, 1966 (#66000429) |

Great Falls 47°31′52″N 111°09′05″W / 47.531111°N 111.151389°W | Cascade | The Lewis and Clark Expedition undertook an 18-mile, 31-day portage at Great Falls, one of the most difficult ordeals of their westward trip. The Great Falls Portage NHL is within Giant Springs State Park.[10] |

| 13 | Great Northern Railway Buildings |  |

May 28, 1987 (#87001453) |

Glacier National Park 48°46′05″N 113°46′11″W / 48.76812°N 113.76982°W | Flathead and Glacier | These lodges or associated buildings, dated c.1913-1915, represent European-style hostelries unique among NPS concessions. The landmark contains 5 building groups: Granite Park Chalet, Many Glacier Hotel, Sperry Chalet, Two Medicine Store, and Belton Chalet |

| 14 | Hagen Site |  |

July 19, 1964 (#66000432) |

Glendive | Dawson | An archeological site representing one of the Crow villages after the tribe had split from the Hidatsa on the Missouri River (c. 1550-1675); site has evidence of horticulture and diet.[11] |

| 15 | Lake McDonald Lodge |  |

May 28, 1987 (#87001447) |

Glacier National Park 48°36′55″N 113°52′41″W / 48.61538°N 113.8781°W | Flathead | A Swiss chalet-style hotel in Glacier National Park.[12] |

| 16 | Lemhi Pass |  |

October 9, 1960 (#66000313) |

Tendoy, ID 44°58′29″N 113°26′41″W / 44.97472°N 113.444722°W | Beaver- head (MT) and Lemhi, ID |

See main listing under Idaho. |

| 17 | Lolo Trail |  |

October 9, 1960 (#66000309) |

Lolo Hot Springs, MT 46°38′07″N 114°34′47″W / 46.635278°N 114.57972°W | Missoula, MT, Clear- water, ID, and Idaho, ID |

|

| 18 | Northeast Entrance Station |  |

May 28, 1987 (#87001435) |

Yellowst. National Park 45°00′10″N 110°00′33″W / 45.00281°N 110.0092°W | Park | Rustic entrance station built in 1935 that is a prime example of form fitting function, in Yellowstone National Park. |

| 19 | Pictograph Cave |  |

July 19, 1964 (#66000439) |

Billings 45°44′12″N 108°25′47″W / 45.73667°N 108.42972°W | Yellow- stone |

One of the key archeological sites used in determining the sequence of prehistoric occupation on the northwestern Plains. The deposits indicate occupation from 2600 BC to after 1800 AD.[13] |

| 20 | Pompey's Pillar |  |

July 23, 1965 (#66000440) |

Pompey's Pillar 45°59′43″N 108°00′20″W / 45.995278°N 108.00556°W | Yellow- stone |

The massive natural block of sandstone was a major landmark on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Clark's signature is carved on its surface.[14] |

| 21 | Rankin Ranch | May 11, 1976 (#76001119) |

Avalanche Gulch, north of Townsend 46°37′46″N 111°34′11″W / 46.629412°N 111.569648°W | Broad- water |

Residence (1923–56) of Jeannette Rankin, first woman elected to U.S. House of Representatives (1916), had two terms 1917-19 & 1941-43, only member to oppose the declaration of war against Japan in 1941.[15] | |

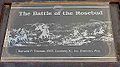

| 22 | Rosebud Battlefield-Where the Girl Saved Her Brother |  |

October 6, 2008 (#72000735) |

Kirby 45°13′17″N 106°59′21″W / 45.221389°N 106.989167°W | Big Horn | Site of the Battle of the Rosebud[16] |

| 23 | Charles M. Russell House and Studio |  |

December 21, 1965 (#66000430) |

Great Falls 47°30′35″N 111°17′09″W / 47.509650°N 111.285921°W | Cascade | Home and studio of artist Charles M. Russell.[17] |

| 24 | Three Forks of the Missouri |  |

October 9, 1960 (#66000433) |

Three Forks 45°55′39″N 111°30′18″W / 45.9275°N 111.505°W | Gallatin | Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, first European-American to visit this spot, concluded the Missouri River originated where the Three Forks joined.[18] |

| 25 | Travelers Rest |  |

October 9, 1960 (#66000437) |

Lolo 46°45′00″N 114°05′20″W / 46.75°N 114.08889°W | Missoula | Campsite used during the westward passage of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805 as the party prepared to cross the Bitterroot Mountains, and again during return passage in 1806. |

| 26 | Virginia City Historic District |  |

July 4, 1961 (#66000435) |

Virginia City 45°17′37″N 111°56′41″W / 45.293611°N 111.944722°W | Madison | More than 200 historic 19th century buildings remain in this 1860s mining town; it also served as the Montana Territorial Capitol during the same period. |

| 27 | Burton K. Wheeler House |  |

December 8, 1976 (#76001129) |

Butte 46°00′20″N 112°31′17″W / 46.00565°N 112.52151°W | Silver Bow | Former residence of noted Montana Senator Burton K. Wheeler.[19] |

| 28 | Wolf Mountains Battlefield-Where Big Crow walked Back and Forth |  |

October 6, 2008 (#00001617) |

Birney 45°17′18″N 106°34′53″W / 45.28823°N 106.58146°W | Rosebud | Site of the Battle of Wolf Mountain.[20] |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ National Park Service. "National Historic Landmarks Program: Questions & Answers". Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ Numbers represent an alphabetical ordering by significant words. Various colorings, defined here, differentiate National Historic Landmarks and historic districts from other NRHP buildings, structures, sites or objects.

- ^ The eight-digit number below each date is the number assigned to each location in the National Register Information System database, which can be viewed by clicking the number.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-306 Archived 2009-03-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-303 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS webpage: NPS-gov-940 Archived 2012-09-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS webpage: NPS-gov-919** Archived 2008-01-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS webpage: NPS-gov-300 Archived 2008-04-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS webpage: NPS-gov-1235 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS webpage: NPS-gov-298 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-301 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-1630 Archived 2005-03-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-307 Archived 2012-09-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-308 Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-1630 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, April 2009, webpage: "National Historic Landmarks Program (NHL)". Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2009..

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-299 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-302 Archived 2003-11-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, March 2009, webpage: NPS-gov-1631 Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ NPS, April 2009, webpage: "National Historic Landmarks Program (NHL)". Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2009..