The imperial campaigns (Ottoman Turkish: سفر همايون, romanized: sefer-i humāyūn)[Note 1] were a series of campaigns led by Suleiman, who was the tenth and longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire.[1]

| Campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe and the Ottoman wars in the Near East | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

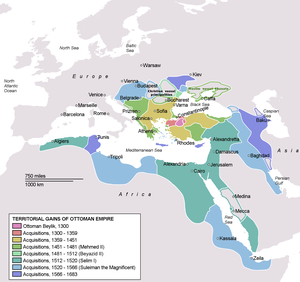

In 1520, Suleiman became the Sultan at the age of 25, succeeding his father Selim I (who had himself more than doubled the size of the Empire through his own campaigns), and began a series of military conquests.[2] In addition to campaigns led by his viziers and admirals, Suleiman personally led 13 campaigns.[3][Note 2] The total duration of these campaigns was ten years and three months.[4] The details of the first eight campaigns were preserved in Suleiman's diary.[3] His main opponents were Ferdinand I from the House of Habsburg (later the Holy Roman Emperor), and Tahmasp I of Safavid Persia. Most of Suleiman's campaigns were directed to the west.[5] In 1521 the Ottomans captured Belgrade, which had been besieged unsuccessfully by Mehmed the Conqueror, and in 1526 the Battle of Mohács ended with the defeat of Louis II of Hungary.[5] But Suleiman did not annex most of Hungary till 1541. In 1529 Suleiman's conquests were checked at the siege of Vienna. Although from 1529 to 1566 the borders of the Ottoman Empire moved further west, none of the later campaigns achieved the decisive victory that would secure the new Ottoman possessions.[6] He annexed most of the Near East in his conflict with the Safavids.[4] Under Suleiman's rule, the Ottoman annexed large swathes of North Africa as far west as Algeria, while the Ottoman fleet dominated the Mediterranean Sea.[7]

In January 1566 Suleiman, who had ruled the Ottoman Empire for 46 years, went to war for the last time.[8] Although he was 72 years old and suffered gout to the extent that he was carried on a litter, he nominally commanded his thirteenth military campaign.[8] On 1 May 1566, the Sultan left Constantinople at the head of one of the largest armies he had ever commanded.[8] Nikola Šubić Zrinski's success in an attack upon an Ottoman encampment at Siklós, and as a consequence Suleiman's siege of Szigetvár, blocked Ottoman's line of advance towards Vienna.[9] Although an Ottoman victory, the battle stopped the Ottoman push for Vienna that year, since Suleiman died during the siege.[10]

Usage

editThe table's columns (except for Notes and Images) are sortable by pressing the arrows symbols. The following gives an overview of what is included in the table and how the sorting works.

- #: number of the campaigns which Suleiman personally led. This does not include the campaigns led by his viziers and admirals.

- Campaign: name of the campaigns (alternative names for some campaigns are included below the first name)

Campaigns in continental Europe

Campaigns in the Near East

Amphibious campaigns in the Mediterranean

- Campaign dates: time period of campaign with opening and terminal dates of each campaign

- Notes: Campaign path which is in small font, describes Suleiman's exact direction in particular campaign. Suleiman's main battle/target is bolded. Below the campaign path there is a short description of the campaign, covering all major events.

- Image: presented image is closely related with campaign, usually showing the main battle/target

Campaigns

edit| # | Campaign[11] | Campaign dates[11] | Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belgrade or First Hungarian (Angurus) |

18 May 1521 – 19 October 1521 |

Campaign path: Filibe (Plovdiv)–Niš–Belgrade–Semendire (Smederevo)[11] The Ottomans under Suleiman made preparations for the conquest of Belgrade, which had been besieged unsuccessfully by Mehmed the Conqueror.[5] With a garrison of only 700 men, and receiving no aid from the Kingdom of Hungary, Belgrade fell in August 1521.[12] |

Belgrade in 16th century |

| 2 | Rhodes | 16 June 1522 – 30 January 1523 |

Campaign path: Kütahya–Denizli–Rhodes–Alaşehir[11] The Siege of Rhodes was the second and ultimately successful attempt by the Ottomans to expel the Knights of Rhodes (Knights Hospitaller) from their island stronghold and thereby secure Ottoman control of the Eastern Mediterranean. In the summer of 1522, Suleiman dispatched an armada of some 400 ships while personally leading an army of 100,000 across Asia Minor to a point opposite the island.[13] Following a siege of five months, Rhodes capitulated and Suleiman allowed the Knights of Rhodes to depart.[13] |

Siege of Rhodes |

| 3 | Mohács or Second Hungarian |

23 April 1526 – 13 November 1526 |

Campaign path: Belgrade–Peterwardein (Petrovaradin)–Eszek (Osijek)–Mohács–Buda (Ofen)–Szeged(Szegedin)–Bécse (Bečej)[11] On 29 August 1526, at the Battle of Mohács, the Christian forces led by Louis II of Hungary were defeated by Ottoman forces led by Suleiman.[14] After king Louis was killed in the battle, both the Kingdom of Hungary and Kingdom of Croatia became disputed territories between the Habsburg and Ottoman empires. While the nobles of both Hungary and Croatia nominated Austrian archduke Ferdinand I as the king of Hungary and Croatia,[15] the Ottomans appointed John Zápolya as the king.[16] After Hungarian resistance collapsed, the Ottoman Empire became the pre-eminent power in Southeast Europe.[17] |

Battle of Mohács |

| 4 | Vienna | 10 May 1529 – 16 December 1529 |

Campaign path: Mohács–Buda(Ofen)–Komorn (Komárom)–Győr–Vienna[11] The Ottomans' first attempt to capture Vienna failed in 1529.[18][19][20] Under Charles V and his brother Ferdinand, the Habsburgs reoccupied Buda, but Suleiman quickly regained control of Buda, and in the following autumn laid siege to Vienna.[18] Although a failure, the siege signalled the pinnacle of the Ottoman Empire's power and the maximum extent of Ottoman expansion in central Europe.[18] The campaign can also be viewed as a success, since John Zápolya was to rule thereafter most of Hungary as a vassal of Ottomans until his death.[21] |

Siege of Vienna |

| 5 | Kőszeg (Güns) or Great German (Turkish: Büyük Alman) |

25 April 1532 – 21 November 1532 |

Campaign path: Eszek (Osijek)–Babócsa–Rum–Styria–Güns (Kőszeg)–Pettau (Ptuj)–Varaždin–Požega[11] The Ottomans' second attempt to conquer Vienna failed in 1532.[22] After Suleiman crossed the river Drava at Osijek, instead of taking the usual route for Vienna, he turned westwards into Ferdinand's held Hungarian territory.[23] After taking a few minor places, he laid siege to a border town called Güns (Kőszeg).[23] According to some sources Suleiman was repulsed in the Siege of Güns.[22][24][25] In another account, Croatian baron Nikola Jurišić who was the city's commander, was offered terms for a nominal surrender.[23] In both versions, Suleiman withdrew at the arrival of the August rains.[23][26] Although he was stopped at Kőszeg and failed to conquer Vienna, since Ferdinand and Charles evaded an open field battle, Suleiman additionally secured his possession in Hungary by conquering several forts.[27] Immediately after the Ottoman withdraw, Ferdinand reoccupied devastated territory in Austria and Hungary.[28] Nevertheless, a peace treaty was concluded a year later with Ferdinand.[29] The treaty confirmed the right of John Zápolya as a king of all Hungary, but recognised Ferdinand's possession of that part of the country that enjoyed the status quo.[29] |

Monument of the Siege of Güns (Kőszeg) |

| 6 | Persia or Turkish: Irakeyn[Note 3] |

11 June 1534 – 8 January 1536 |

Campaign path: Konya–Sivas–Erzurum–Erciş–Tabriz–Sultaniye (Soltaniyeh)–Dargazin–Qasr-e Shirin–Baghdad–Irbil (Arbil)–Zagros–Tabriz–Khoy–Lake Van–Amid–Urfa (Şanlıurfa)–Aleppo–Adana–Konya–Istanbul[11] The Capture of Baghdad by Suleiman from the Safavid dynasty under Tahmasp I was part of the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555).[30] Baghdad was taken without resistance, as the Safavid government fled and left the city undefended.[30] |

16th century map of Tabriz, Matrakçı Nasuh |

| 7 | Corfu or Apulia (Turkish: Pulya) |

17 May 1537 – 22 November 1537 |

Campaign path: Filibe (Plovdiv)–Uskup (Skoplje)–Elbasan–Avlonya (Vlorë)–Corfu–Manastir (Bitola)–Selanik (Thessaloniki)[11] As a part of the Franco-Ottoman alliance, the Ottomans invaded Apulia in Southern Italy.[31] Although the Ottomans produced much terror, Otranto and Brindisi held out.[31] Since France failed to meet his commitment, Suleiman abandoned the campaign in Italy, and led the siege of Corfu against the Venetian-held island of Corfu.[31] It was part of the Ottoman–Venetian War (1537–1540). The Ottomans failed to capture Corfu.[32][33] |

Corfu in 16th century |

| 8 | Moldavia or Turkish: Kara Boğdan |

9 July 1538 – 27 November 1538 |

Campaign path: Babadaği (Babadag)–Jassy (Iaşi)–Suceava[11] In 1538 Suleiman invaded Moldavia.[34] The prince Peter IV Rareş fled into exile in Transylvania, and Suleiman occupied major cities of Moldavia, including the capital of Jassy (Iaşi).[34] He appointed Ştefan as the new king of Moldavia.[35] Suleiman also occupied Suceava and annexed Bessarabia.[34] |

Suceava Castle |

| 9 | Hungary or Buda (Turkish: Budin) |

20 June 1541 – 27 November 1541 |

Campaign path: Ofen (Buda)[11] When John Zápolya died, Ferdinand realized an opportunity to invade Hungary.[36] The Habsburgs attempted a siege of Buda (1541), which was governed by Isabella Jagiellon with support from Suleiman.[31] Suleiman took personal command of the Ottoman relief army, reached Buda, and defeated the Habsburgs.[31] Suleiman annexed Hungary to the Ottoman realm and appointed Isabella as queen regent of Transylvania (Turkish: Erdel).[37] |

Siege of Buda |

| 10 | Hungary or Gran (Esztergom) |

23 April 1543 – 16 November 1543 |

Campaign path: Eszek (Osijek)–Siklós–Ofen (Buda)–Gran (Esztergom)–Tata–Pest[11] In April 1543 Suleiman returned to capture the Hungarian towns that had gone over to the Austrians during Ferdinand's last invasion.[31] In August 1543 the Ottomans succeeded in the Siege of Esztergom (1543), which was followed by the capture of three Hungarian cities, providing better security for Buda: Székesfehérvár, Siklós and Szeged.[31] |

Siege of Esztergom |

| 11 | Persia or Iran |

29 March 1548 – 21 December 1549 |

Campaign path: Tabriz–Van–Muş–Bitlis–Amid (Diyarbakır)–Ergani–Harput (Elâzığ)–Amid–Urfa–Birecik–Aleppo–Hama–Hims–Antioch[11] During the Ottoman–Safavid Wars, Persia was accustomed to attacking the Ottomans from behind.[36] Attempting to defeat the Shah once and for all, Suleiman embarked on a second campaign against the Safavid dynasty. Suleiman abandoned the campaign with temporary Ottoman gains in Tabriz and Persian Armenia, a lasting presence in the province of Van, and some forts in Georgia.[36] |

Walled City of Van |

| 12 | Persia or Nakhchivan |

28 August 1553 – 31 July 1555 |

Campaign path: Kütahya–Ereğli (where Suleiman executed prince Mustafa)–Aleppo (for the winter)–Amid (Diyarbakır)–Erzurum–Kars–Karabağ (Nagorno-Karabakh)–Nahçıvan (Nakhchivan)–Erzurum–Sivas–Amasya (second winter)[11] Suleiman began his third and final campaign against the Safavid Empire, in which he first lost and then regained Erzurum. Ottoman territorial gains were secured by the Peace of Amasya in 1555. Suleiman returned Tabriz, but kept Baghdad, lower Mesopotamia, the mouths of the Euphrates and Tigris, and part of the Persian Gulf coast.[38] (Şehzade Mustafa, the heir apparent was executed during the campaign) |

Suleiman marching in Nakhichevan |

| 13 | Szigetvár (Szigeth)[Note 4] | 1 May 1566 – 6 September 1566 Suleiman died a day before the Ottoman victory |

Campaign path: Siklós–Pécs–Szigetvár (on 6 September the Suleiman died)[11] During an Ottoman advance towards Vienna and learning of the Zrinsky's success in an attack upon a Turkish encampment at Siklós, Suleiman decided to postpone his attack on Eger (German: Erlau) and instead attack Zrinsky's fortress at Szigetvár to eliminate him as a threat.[39][40] During the Siege of Szigetvár, Croatian commander Nikola Šubić Zrinski died in the final charge, and Suleiman died in his tent from natural causes, a day before the Ottoman victory.[10] The prolonged resistance at Szigetvár delayed the Ottoman push for Vienna that year.[10][41] Even if Suleiman had lived his army could not have achieved much in the short time that remained between the fall of Szigetvár and the onset of winter.[41] |

Siege of Szigetvár |

Suleiman's opponents

edit-

Louis II of Hungary

Campaigns 1 (Belgrade) and 3 (Mohács) -

Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam

Campaign 2 (Rhodes) -

Ferdinand I

Campaigns 4 (Vienna), 5 (Güns/Kőszeg), 9 (Buda), and 10 (Gran/Esztergom) -

Tahmasp I

Campaigns 6 (Iraqain), 11 (Iran), and 12 (Nakhchivan) -

Andrea Gritti

Campaign 7 (Corfu) -

Peter IV Rareş

Campaign 8 (Moldavia) -

Maximilian II

Campaign 13 (Szigetvár)

See also

editNotes

edit- Footnotes

- ^ The Ottoman Turkish name for the imperial campaigns, according to Şemseddin Sâmî (Frashëri) in his book (Kamûs-ül Â'lâm)

- ^ Some sources list 14 campaigns as Suleiman did made preparations for a campaign against his son Şehzade Beyazıt in 1559, but he renounced campaigning upon the latter's retreat to Persia (Encyclopaedia metropolitana: or Universal dictionary of knowledge, Volume 13. (1845) B. Fellowes).

- ^ The alternative name of Suleiman's sixth campaign is "Iraqain" (Turkish: Irakeyn), which refers to "The Two Iraqs": 'Irāq-i 'Ajem and 'Irāq-i 'Arab

- ^ Suleiman nominally commanded his thirteenth military campaign, but his Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha was the real operational commander of the Ottoman forces (Sakaoğlu (1999), pp. 140–141.).

- Citations

- ^ Zürcher (1999), p. 38.

- ^ Turnbull (2003), p. 45.

- ^ a b Pitcher (1972), p. 111.

- ^ a b Pitcher (1972), p. 112.

- ^ a b c Faroqhi (2008), p. 62.

- ^ Uyar and Erickson (2009), p. 74.

- ^ Mansel (2006), p. 61.

- ^ a b c Turnbull (2003), p. 55.

- ^ Turnbull (2003), p. 56.

- ^ a b c Turnbull (2003), p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Pitcher (1972), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Imber (2002), p. 49.

- ^ a b Kinross (1979), p. 176.

- ^ Turnbull (2003), p. 49.

- ^ Corvisier and Childs (1994), p. 289.

- ^ Turnbull (2003), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Kinross (1979), p. 187.

- ^ a b c Turnbull (2003), pp. 49–51.

- ^ Sander (1897), p. 49.

- ^ Egemen (2002), p. 505.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, Expo 70 ed., Vol 21, p.388

- ^ a b Wheatcroft (2009), p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Turnbull (2003), p. 51.

- ^ Thompson (1996), p. 442.

- ^ Ágoston and Alan Masters (2009), p. 583.

- ^ Vambery, p. 298.

- ^ Akgunduz and Ozturk (2011), p. 184.

- ^ Black (1996), p. 26.

- ^ a b Turnbull (2003), pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Cavendish (2006), p. 193.

- ^ a b c d e f g Turnbull (2003), p. 52.

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 432–433.

- ^ Kurat (1966), p. 49.

- ^ a b c Shaw (1976), p. 100.

- ^ Iorga (2005), p. 356. (Vol 2)

- ^ a b c Akgunduz and Ozturk (2011), p. 185.

- ^ Iorga (2005), pp. 26–27. (Vol 3)

- ^ Kinross (1979), p. 236.

- ^ Setton (1984), pp. 845–846.

- ^ Shelton (1867), pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Elliott (2000), p. 118.

References

edit- Ágoston, Gábor; Alan Masters, Bruce (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1.

- Akgunduz, Ahmed; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History: Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. ISBN 978-90-902610-8-9.

- Black, Jeremy (1996). Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47033-9.

- Cavendish, Marshall (2006). World and Its Peoples: The Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- Corvisier, André; Childs, John (1994). A dictionary of military history and the art of war. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-16848-5.

- Egemen, Feridun (2002). "Sultan Süleyman Çağı ve Cihan Devleti", Türkler, Cilt 9 (in Turkish). Yeni Türkiye Yayınları. ISBN 978-975-6782-42-2.

- Elliott, John Huxtable (2000). Europe divided, 1559–1598. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21780-0.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2008). The Ottoman Empire: a short history. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55876-449-1.

- Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650 : The Structure of Power. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-61386-3.

- Iorga, Nicolae (2005). Osmanlı İmparatorluğu tarihi, Vol 2 : 1451–1538 and Vol 3 : 1538–1640 (translated by Nilüfer Epçeli) (in Turkish). Yeditepe. ISBN 978-975-6480-17-5.

- Kinross, Patrick (1979). The Ottoman centuries : The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-08093-8.

- Kurat, Akdes Nimet (1966). Türkiye ve İdil boyu (in Turkish). Ankara Üniversitesi Basımevi.

- Mansel, Philip (2006). Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6880-0.

- Pitcher, Donald Edgar (1972). An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire. Brill.

- Sander, Oral (1987). Osmanlı diplomasi tarihi üzerine bir deneme (in Turkish). Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi.

- Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2001). Bu Mülkün Sultanları: 36 Osmanlı Padişahi (in Turkish). Oğlak Yayıncılık ve Reklamcılık. ISBN 978-975-329-299-3.

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The Sixteenth Century. Vol. III. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-161-3.

- Shaw, Stanford J. (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey. Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7.

- Shelton, Edward (1867). The book of battles: or, Daring deeds by land and sea. Houlston and Wright.

- Thompson, Bard (1996). Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6348-5.

- Turnbull, Stephen R (2003). The Ottoman Empire, 1326–1699. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-415-96913-0.

- Uyar, Mesut; J. Erickson, Edward (2009). A military history of the Ottomans: from Osman to Atatürk. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-98876-0.

- Vambery, Armin. Hungary in Ancient Mediaeval and Modern Times. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-4400-9034-9.

- Wheatcroft, Andrew (2009). The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01374-6.

- Zürcher, Erik Jan (1999). Arming the state: military conscription in the Middle East and Central Asia, 1775–1925. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-404-7.

Further reading

edit- Finkel, Caroline (2005). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1923. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02396-7.

- Imber, Colin (2009). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The Structure of Power (2 ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-57451-9.