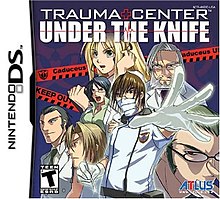

Trauma Center: Under the Knife

Trauma Center: Under the Knife[a] is a simulation video game developed by Atlus for the Nintendo DS. The debut entry in the Trauma Center series, it was published in Japan and North America by Atlus in 2005, and by Nintendo in Europe in 2006. Set in a near future where medical science can cure previously incurable diseases, the world's population panics when a new manmade disease called GUILT begins to spread. Doctor Derek Stiles, a surgeon possessing a mystical "Healing Touch", works with the medical research organization Caduceus to find a cure to GUILT. The gameplay combines surgery-based simulation relying on the DS's touchscreen controls with a story told as a visual novel.

| Trauma Center: Under the Knife | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Atlus |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Director(s) | Kazuya Niinou |

| Producer(s) | Katsura Hashino |

| Designer(s) | Makoto Kitano |

| Programmer(s) | Nobuyoshi Miwa |

| Artist(s) | Maguro Ikehata |

| Writer(s) | Shogo Isogai |

| Composer(s) | Kenichi Tsuchiya Shoji Meguro Kenichi Kikkawa |

| Series | Trauma Center |

| Platform(s) | Nintendo DS |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Simulation, visual novel |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Designed to take advantage of the DS's control options after planned development for earlier consoles stalled due to inadequate hardware, development lasted just over a year. Its early inspirations included Western television series ER and Chicago Hope, with science fiction elements incorporated during a later stage. Development proved challenging for the staff, who were veterans of the Megami Tensei franchise and had little experience with genres outside role-playing.

The game was positively reviewed by journalists, who praised the title for its use of the DS controls while criticising its difficulty spikes and repetition. While a commercial disappointment in Japan, it sold beyond expectations in both North America and Europe, boosting Atlus' profits for that year. A remake for the Wii, Trauma Center: Second Opinion, released the following year. A DS sequel, Under the Knife 2, was released in 2008.

Gameplay

editTrauma Center: Under the Knife is a video game that combines surgical simulation gameplay with storytelling using non-interactive visual novel segments using static scenes, character portraits, text boxes, and voice clips during gameplay segments.[1][2][3] The top screen of the Nintendo DS is dedicated to story sequences and level statistics displayed as 2D artwork, while the bottom touch screen is dedicated to the operations themselves rendered using 3D models.[2][4] Players take on the role of protagonist Derek Stiles, a young surgeon with a mystical ability called the Healing Touch. Each operation tasks players with curing the patient of one or multiple ailments within a time limit.[4][5]

Operations take place from a first-person view over the affected area.[6] The ten available surgical tools are required for different operations and injuries, selected using icons along the edges of the touch screen.[4][7] Each operation is prefaced by a briefing, describing the patient's condition and possible treatments. Depending on the operation, players may need to drain blood pools obstructing the operating area, use a surgical laser to treat small tumors or virus clusters, a scalpel to open incisions or excise larger tumors, a scanner for detecting hidden ailments, forceps to close wounds and introduce or extract objects, a syringe to inject a variety of medications, and sutures to sew up both wounds and incisions. The player must frequently apply antibiotic gel to treat minor injuries and prevent infection. The player may also require the "hand" option for situations such as a heart massage or placing objects such as synthetic membranes. During one operation, several of these tools will be needed. Each operation ends with the sutured wound being treated and a bandage being applied.[8] All of these actions are accomplished using the DS stylus.[4]

Operations range from treating surface wounds and extraction operations, to special operations where Stiles must confront strains of a man-made parasitic infection dubbed GUILT. These strains can be highly mobile, complicating the operation.[4] Some operations are affected by environmental hazards, such as turbulence on a plane.[7] A key story-based ability is Stiles's Healing Touch, triggered by drawing a five-pointed star on the touch screen. The Healing Touch slows down time for a limited period, allowing the player to perform operation actions without the patient dying.[2][5] Points are awarded with how fast and efficiently an action is performed, and graded from "Bad" to "Cool".[5] After each operation, the player is graded on their performances, with rankings going from "C" (the lowest) to "S" (the highest).[5][7] After an operation is completed in the story mode, players can attempt it again in the Challenge mode for a higher score.[5] The player can save their game after each story chapter.[7][8] If the patient dies or the timer runs out, the game ends and the player must restart from their last save.[8]

Synopsis

editTrauma Center is set in a near future Earth of 2018, where medical science has advanced to the point that previously major diseases such as AIDS and cancer are easily cured. The world's pioneering medical foundation is Caduceus, a multinational, semi-covert organization dedicated to researching and curing intractable diseases.[9] The story follows Derek Stiles, a young doctor who discovers his mystical Healing Touch during a difficult operation on an emergency patient from a car crash. After treating another patient infected with an unknown parasitic disease, Stiles is offered a position at Caduceus, which he accepts. The parasite is known as the Ganglia Utrophin Immuno Latency Toxin (GUILT for short), a manmade disease being distributed by the medical terrorist cell, Delphi. Along with his companion and assistant, nurse Angela "Angie" Thompson, Stiles begins confronting new strains of GUILT in different patients, along with surviving attempts on his life by Delphi. During their work, several Caduceus staff members are infected, including the director, Richard Anderson. While the strain is eventually removed, Anderson ultimately succumbs to the stress on his body from multiple operations and gives his position to Stiles's former superior, Robert Hoffman.

During an attempted raid by Delphi on Caduceus, the intruder is identified as Angie's father Kenneth Blackwell. Trailing him to a Delphi laboratory, Stiles and Angie successfully treat a highly-virulent GUILT strain, first in a nascent form in a test subject, and then in Blackwell himself. Once cured, Blackwell offers his full cooperation and rejects Caduceus's offer of amnesty, wishing to serve out his term in prison to atone for his actions. Blackwell's information leads to the location of Delphi's headquarters, which consisted of an ocean vessel. When Stiles and Angie assist with a raid in cooperation with Caduceus Europe, they find that Delphi has been using children to incubate GUILT, and after curing the patients, they encounter Delphi's leader, Adam, now a vegetable host for all seven strains of GUILT, as well as a unique, eighth strain known as "Bliss." Caduceus Europe impound Adam's remains, and Stiles is hailed for his actions.

Development

editThe original plan for Trauma Center was created by the game's producer Katsura Hashino. During this early stage, many staff compared the game to similar surgery simulations for Windows.[6] The concept behind Trauma Center originated several years before development started. While Atlus had explored the possibilities of a surgical simulation game, gaming hardware at the time was not able to realize their vision. This changed with internal previewing of the DS, which had the controls and functions to make the simulation elements work as intended. Planning for the game began in the summer of 2004.[10] Most of the staff were veterans of Atlus's Megami Tensei role-playing video game (RPG) franchise, making the development a difficult one due to its thematic and gameplay differences. Production proved a challenge due to the new gaming hardware and its deviation from the RPG mechanics Atlus was known for. One of the more difficult elements was getting the gameplay to function, which they finally achieved after settling on a first-person perspective for surgery.[6]

According to director Kazuya Niinou, the team drew inspiration from Western television series including ER and Chicago Hope, and unspecified Japanese television series and comics during their early work.[10] The scenario was written by Shogo Isogai, who faced problems when creating a narrative that would be respectful towards the medical profession while being fun, and confront very different themes to his work on the Megami Tensei series. While keeping in line with creating a medical drama, Isogai was told to add science fiction elements, which was a relief for him as he did not need to be accurate to a field he knew little about. The team needed to think carefully about the naming of GUILT strains, which were all derived from Greek words, which sharply contrasted their free borrowing of demon names for the Megami Tensei series. They also strove to push away from the common video game motif of seemingly glorifying death.[6] The characters were designed by Maguro Ikehata.[11][12] The art style was described as "very anime-styled".[13] The operation graphics were originally very stylised, but Hashino disapproved. While they decided against being too realistic, they managed to strike an aesthetic balance between realistic and cartoon graphics.[6]

The music was composed by Kenichi Tsuchiya, Shoji Meguro and Kenichi Kikkawa. Meguro and Tsuchiya were both veterans of the Megami Tensei franchise, particularly its Persona and Devil Summoner subseries.[14] The opening was one of the themes created by Meguro, who acted as sound director for the project. He found the limited sound environment even more of a challenge than earlier consoles he had composed for. Tsuchiya's work focused on environmental themes and general sound design, while Kikkawa's scores focused on orchestral tracks.[6] While Meguro and Kikkawa composed standard-definition music and reduced it to fit into the DS sound environment, Tsuchiya composed his tracks within the sound environment. At the time, Atlus did not have a MIDI interface for DS composition, so the composers had to guess what the sound would be like when transplanted into the game.[14]

Release

editThe game was first announced in July 2004 alongside five other Atlus titles for the DS.[15] The game was released in Japan on June 16, 2005.[16] A commercial demo was released through Nintendo's online store on May 29.[17] While it lacked the high amount of blood and gore that would have earned it a mature rating, its content still merited a CERO rating of "B", indicating an age range of early teens and up.[6][10] Its release was supported by a guidebook published by Enterbrain in July of that same year.[18] A soundtrack album was released by Sweep Records in October 2011.[14]

The game was first revealed under its English name at the 2005 Electronic Entertainment Expo.[19] It released in North America on October 4.[20] The game was localized for the West by Atlus USA.[13] For the game's English version, the game's setting was changed from Japan to North America. Derek Stiles's English name was written as a pun on the word "stylus", referencing the DS stylus.[21] The English dub was handled by PCP Productions, who had previously worked with Atlus on Shin Megami Tensei: Digital Devil Saga.[22] Voice acting was restricted to shoutouts during operations, while Stiles himself did not have a voice actor.[23] Due to their lack of a European branch, Atlus USA did not publish the game in the region. The game was instead published by Nintendo of Europe on April 28, 2006.[13][24][25]

Reception

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 81/100 (45 reviews)[26] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| 1Up.com | B[27] |

| Eurogamer | 7/10[2] |

| Famitsu | 31/40[28] |

| GamePro | [29] |

| GameSpot | 7.8/10[4] |

| GameSpy | [30] |

| IGN | 8/10[5] |

| Official Nintendo Magazine | 80%[7] |

| PALGN | 7/10[31] |

In Japan, Trauma Center did not appear in Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu's top 500 best-selling titles for 2005, indicating sales of less than 15,000 units.[32] In contrast, the North American release was described by Atlus staff as "absolutely fabulous", with sales going "off the charts".[33] The game's popularity prompted Atlus to issue further print runs of the game.[34] The game also met with strong sales in Europe.[35] While Atlus had seen financial losses prior to 2006, the international success of Trauma Center contributed to the company making a profit.[36]

Famitsu praised the game's innovative use of the touch screen,[28] while Christian Nutt of 1UP.com called the game a standout title for the DS due to its polished controls and unconventional premise.[27] Eurogamer's Tom Bramwell praised the gameplay and[specify], although he found faults in the game's presentation and confusing or arbitrary mechanics.[2] GamePro called the game "a cure for what has been a spell of mediocrity on the DS".[29] GameSpot's Alex Navarro praised the game's balancing of narrative and arcade-style gameplay.[4]

Justin Leeper, writing for GameSpy, felt that Trauma Center could succeed in appealing to a broader audience than other titles with unconventional gameplay ideas.[30] Craig Harris of IGN was surprised by how much he enjoyed his time playing.[5] Tom East of Official Nintendo Magazine called Trauma Center "engaging, fun and highly original",[7] and Matt Keller of PALGN generally enjoyed the gameplay experience despite its short length and other issues with the difficulty and graphics.[31]

The use of the DS touch screen and stylus were generally lauded by critics;[2][4][5][7][30] East called it a concept only made possible by the hardware,[7] while Leeper had issues with stylus motions registering.[30] The story was generally praised, with many calling it both silly and engaging,[2][4][5][7][29] and a few noting its handling of mature themes.[2][27] Others also negatively noted the large amount of text, which slowed the game's pace.[2][7] Difficulty spikes in later portions of the game, lack of room for improvisation, and general repetitiveness were noted by reviewers as detrimental factors.[2][4][5][7][27][28][31]

Legacy

editDuring their 2005 gaming awards, GameSpot nominated Trauma Center in their "Most Innovative Game" category.[37] In the years following its release, Trauma Center would become a notable success for Atlus, breaking into mainstream gaming when they had previously been restricted to niche success. In a feature by Jess Ragan for 1UP.com, Trauma Center: Under the Knife was described as having "helped pull the Nintendo DS out of a debilitating software drought and demonstrated the system's potential to both hardcore gamers and skeptical outsiders alike".[38] Website VentureBeat listed Under the Knife as one of the most memorable games of 2005 due to breaking away from gaming trends and creating an experience focused on saving lives.[39]

Following the release of Under the Knife, most of Hashino's team shifted to work on the Persona series, with a small number of staff being assigned to form a new team for further development of the series.[40] This group would be known internally as "CadukeTeam".[41] The Trauma Center series would be continued with three subsequent games on Nintendo hardware; Trauma Center: New Blood for the Wii in 2007, the direct sequel Trauma Center: Under the Knife 2, released in 2008 for the DS; and Trauma Team for the Wii in 2010.[1] A remake of Under the Knife, Trauma Center: Second Opinion, was released for the Wii in 2006 as a launch title for the console.[1][42] In a series retrospective, Peter Davison of USGamer noted both the series' notable position in Atlus's gaming library, and how the titles made use of the Nintendo console mechanics.[1]

Notes

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d Davison, Peter (2013-08-07). "It's Time We Had a New Trauma Center". USGamer. Archived from the original on 2016-02-17. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bramwell, Tom (2005-11-01). "Trauma Center: Under the Knife Review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ "Trauma Center: Under the Knife". Atlus. Archived from the original on 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Navarro, Alex (2005-10-06). "Trauma Center: Under the Knife Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Harris, Craig (2005-10-07). "Trauma Center: Under the Knife Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g :::超執刀 カドゥケウス:::. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2006-08-24. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k East, Tom (2008-01-10). "Review: Trauma Center: Under the Knife". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ a b c "Trauma Center: Under the Knife - System". Atlus. Archived from the original on 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Behind the Scalpel - The Story of Trauma Center". Atlus. Archived from the original on 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- ^ a b c Nintendo Inside Special - 超執刀 カドゥケウス. Nintendo Inside (in Japanese). 2005-04-16. Archived from the original on 2006-07-08. Retrieved 2018-12-01. Translation[usurped]

- ^ Atlus (2005-10-04). Trauma Center: Under the Knife (Nintendo DS). Atlus USA. Scene: Credits.

- ^ :::超執刀 カドゥケウス::: 4コマ漫画 - 「貫禄」作・画 池端 まぐろ. Atlus (in Japanese). 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ a b c Schaedel, Nick (2006-09-02). "Sliced Gaming Feature: Trauma Centre Interview". Sliced Gaming. Archived from the original on 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b c 超執刀カドゥケウス サウンドトラック. Sweep Record (in Japanese). 22 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-06-08. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ Niizumi, Hirohiko (2004-08-05). "Atlus reveals DS surgery game". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ [DS] 超執刀 カドゥケウス. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2013-10-24. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ 店頭体験会で『超執刀カドゥケウス』の魅力“タッチパネル手術”に挑戦!. Dengeki Online (in Japanese). 2005-05-19. Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ 超執刀カドゥケウス 公式ガイドブック. Enterbrain (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ^ Adams, David (2005-05-13). "Pre-E3 2005: Atlus Announces Lineup". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-12-21. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Adams, David (2005-10-04). "Trauma Center Opens Its Practice". IGN. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ^ Yip, Spencer (2006-11-20). "Nintendo LA Wii Event: Chat with Atlus". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "PCB - Credits". PCB Productions. Archived from the original on 2019-02-16. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- ^ Casamassina, Matt (2006-09-07). "Interview: Trauma Center: Second Opinion". IGN. Archived from the original on 2014-06-17. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ Graves, Robert (2005-11-16). "NoE To Publish Trauma Center In Europe". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Pallesen, Lasse (2006-02-20). "Trauma Centre: Under the Knife Coming to Europe this April". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on 2018-11-30. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Trauma Center: Under the Knife for Nintendo DS". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ a b c d Nutt, Christian (2005-10-10). "Trauma Center: Under the Knife". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ a b c (DS) 超執刀 カドゥケウス. Famitsu (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2016-07-04. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ a b c "Review: Trauma Center: Under the Knife". GamePro. 2005-10-12. Archived from the original on 2009-06-24. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ a b c d Leeper, Justin. "GameSpy: Trauma Center: Under the Knife Review". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2017-01-14. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ a b c Keller, Matt (2006-04-29). "Trauma Center: Under the Knife Review". PALGN. Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ 2005年テレビゲームソフト売り上げTOP500. Geimin.net. Archived from the original on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ^ Anderson, John (2006-02-06). "Mapping The World With Atlus: Jim Ireton on Atlus' Import Aspirations". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- ^ "Trauma Center Resuscitated". IGN. 2006-06-27. Archived from the original on 2012-12-28. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ Gibson, Ellie (2006-08-09). "Trauma Center for Wii launch". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2016-07-14. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ Winkler, Chris (2006-11-27). "Index Becomes Atlus' New Parent Company". RPGFan. Archived from the original on 2007-05-10. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ "GameSpot's Best and Worst of 2005 awards kick off". GameSpot. 2005-12-16. Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Ragan, Jess (2007-10-10). "Filling a Niche: Bold Video Games that Bucked the Mainstream". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 2016-06-14. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ Kleckner, Stephen (2015-07-28). "10 years later: GamesBeat's most memorable games of 2005". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on 2018-12-01. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- ^ "Exclusive: Behind The Scenes Of Atlus' Persona 4". Gamasutra. 2009-10-06. Archived from the original on 2018-02-21. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- ^ Kanada, Daisuke (2007-10-01). ディレクター金田のカドゥケウス日誌 Vol.01. Atlus (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- ^ Yip, Spencer (2006-05-10). "Surprise titles coming from Atlus". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 2010-02-19. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

Explanatory notes

edit- ^ Known in Japan as Chōshittō Kadukeusu (超執刀 カドゥケウス, lit. Super Surgical Operation: Caduceus)