Healthcare in Somalia is largely in the private sector. It is regulated by the Ministry of Health of the Federal Government of Somalia. In March 2013, the central authorities launched the Health Sector Strategic Plans (HSSPs), a new national health system that aims to provide universal basic healthcare to all citizens by 2016. Somalia has the highest prevalence of mental illness in the world, according to the World Health organization.[1] Some polls have ranked Somalis as the happiest people in Sub-Saharan Africa.[2]

History

editDuring the medieval era, traditional forms of medicine were often used. During the colonial era, due to the distrust that existed in northwest Somalia towards British colonial administrators, there was minimal development in healthcare training. The BMA (British Military Administration) diminished the inflow of Italians into southern Somalia which hampered the building of facilities.[3]

Until the collapse of the federal government in 1991, the organizational and administrative structure of Somalia's healthcare sector was overseen by the Ministry of Health. Regional medical officials enjoyed some authority, but healthcare was largely centralized. The socialist government of former President of Somalia Siad Barre had put an end to private medical practice in 1972.[4] Much of the national budget was devoted to military expenditure, leaving few resources for healthcare, among other services.[5]

Somalia's public healthcare system was largely destroyed during the ensuing civil war. As with other previously nationalized sectors, informal providers have filled the vacuum and replaced the former government monopoly over healthcare, with access to facilities witnessing a significant increase.[6] Many new healthcare centers, clinics, hospitals and pharmacies have in the process been established through home-grown Somali initiatives.[6] The cost of medical consultations and treatment in these facilities is low, at $5.72 per visit in health centers (with a population coverage of 95%), and $1.89–3.97 per outpatient visit and $7.83–13.95 per bed day in primary through tertiary hospitals.[7]

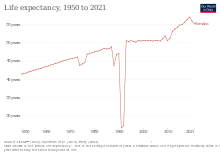

Comparing the 2005–2010 period with the half-decade just prior to the outbreak of the conflict (1985–1990), life expectancy actually increased from an average of 47 years for men and women to 54 years for men and 57 years for women.[8]

Child mortality and morbidity

The last three decades of armed conflicts, lack of functioning government, economic collapse, and disintegration of the health system and other public services - together with recurrent droughts and famines – has turned Somalia into one of the world's most difficult environments for survival. This is bluntly reflected in the poor child health conditions, as twenty per cent of the children die before they reach the age of five, more than one third are underweight, and almost fifty percent experience stunting.[11] The under-five mortality rate in Somalia is among the highest in the world, while the prevalence of malnutrition has remained at record high levels for decades. It is therefore likely that malnutrition contributes to more than half of the under-five deaths in Somalia. Pneumonia, diarrhoea and neonatal causes account for a large proportion of childhood deaths.[12]

The number of one-year-olds fully immunized against measles rose from 30% in 1985–1990 to 40% in 2000–2005,[9][13] and for tuberculosis, it grew nearly 20% from 31% to 50% over the same period.[9][13] In keeping with the trend, the number of infants with low birth weight fell from 16 per 1000 to 0.3, a 15% drop in total over the same timeframe.[9][14] Between 2005 and 2010 as compared to the 1985–1990 period, infant mortality per 1,000 births also fell from 108 to 85.[9][10][15] Significantly,

Maternal mortality

Maternal mortality per 100,000 births fell from 1,600 in the pre-war 1985–1990 half-decade to 850 in the 2015.[9][16][17] The number of physicians per 100,000 people also rose from 3.4 to 4 over the same timeframe,[9][13] as did the percentage of the population with access to sanitation services, which increased from 18% to 26%.[9][13]

According to United Nations Population Fund data on the midwifery workforce, there is a total of 429 midwives (including nurse-midwives) in Somalia, with a density of 1 midwife per 1,000 live births. Eight midwifery institutions presently exist in the country, two of which are private. Midwifery education programs on average last from 12 to 18 months, and operate on a sequential basis. The number of student admissions per total available student places is a maximum 100%, with 180 students enrolled as of 2009. Midwifery is regulated by the government, and a license is required to practice professionally. A live registry is also in place to keep track of licensed midwives. In addition, midwives in the country are officially represented by a local midwives association, with 350 registered members.[18]

According to a 2005 World Health Organization estimate, about 97.9% of Somalia's women and girls underwent female circumcision,[19] a pre-marital custom mainly endemic to Northeast Africa and parts of the Near East.[20][21] Encouraged by women in the community, it is primarily intended to protect chastity, deter promiscuity, and offer protection from assault.[22][23] By 2013, UNICEF in conjunction with the Somali authorities reported that the prevalence rate among 1- to 14-year-old girls in the autonomous northern Puntland and Somaliland regions had dropped to 25% following a social and religious awareness campaign.[24] About 93% of Somalia's male population is also reportedly circumcised.[25]

Somalia has one of the lowest HIV infection rates on the continent. This is attributed to the Muslim nature of Somali society and adherence of Somalis to Islamic morals.[26] While the estimated HIV prevalence rate in Somalia in 1987 (the first case report year) was 1% of adults,[26] a more recent estimate from 2014 now places it at only 0.5% of the nation's adult population.[27]

Although healthcare is now largely concentrated in the private sector, the country's public healthcare system is in the process of being rebuilt, and is overseen by the Ministry of Health.[28] The current Minister of Health is Ahmed Mohamed Mohamud.[29] The autonomous Puntland region maintains its own Ministry of Health,[30] as does the Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia.[31]

Health sector strategic plans

editIn March 2013, the federal government under former Minister of Health Maryam Qaasim launched the Health Sector Strategic Plans (HSSPs) for each of Somalia's constituent zones. The new national health system aims to provide universal basic healthcare to all citizens by 2016. While the government's institutional capacity is developing, UN agencies would in the interim through public-private partnerships administer immunization among other associated health programs. The HSSPs are valued at US$350 million in total, with between 70%-75% earmarked for health services. Once finalized, the new national healthcare system is expected to ameliorate human capital in the health sector, as well as improve funding for health programs and overall health infrastructure.[32]

In May 2014, the Federal Government launched the Essential Package of Health Services (EPHS) within the framework of the Health Sector Strategic Plans.[33] The EPHS was originally designed in 2008 by the Somali Ministry of Health, with the goal of establishing standards for national health services vis-a-vis governmental and private healthcare providers, as well as for partnered UN agencies and NGOs.[34] It aims to provide a holistic spectrum of free health services to all citizens, including in rural areas. With a focus on strengthening reproductive and emergency obstetric care services for women and children, the EPHS's core programmes are to eliminate communicable illness; ameliorate reproductive, neonatal, child and maternal health; improve health control and surveillance, including water and sanitation promotion; supply first-aid and treatment to the terminally ill or wounded; and to treat common illnesses, HIV and other STDs, and tuberculosis. The Somali health authorities are slated to implement the Essential Package of Health Services in nine regions, with UNICEF, UNFPA and WHO representatives providing additional support. The initiative will continue through to the end of 2016, and is expected to ensure that health facilities operate with better equipment, more healthcare workers, and for longer shifts. It is also centered on growing institutional capacity through training medical personnel, health sector reform, and policy development facilitation.[33]

Hospitals

editMedical hospitals and facilities in Somalia's administrative provinces include:[35][36]

- Awdal

- Dr. Aden Farah Abraar Regional Hospital

- Borama Fistula Hospital

- Alaale Hospital

- Al Hayat Medical Centre

- Bakool

- Hudur Hospital

- Banaadir

- Adden Abdulle Hospital

- Kalkaal Hospital

- Banadir Hospital

- Somali Sudanese Specialized Hospital

- Digfeer Hospital

- Dr. Xasan Jis Memory Hospital

- Erdoğan Hospital

- Keysaney Hospital

- Lazaretto Forlanini Hospital

- Martini Hospital

- Medina Hospital

- SOS KDI M&C Hospital

- Yardimeli Hospital (under construction)

- Daryeel Specialist Hospital (since 2016, 4 darjiino)

- Makka Hospital

- MOGADISHU UROLOGICAL CENTER

- Bari

- Bosaso General Hospital

- Qardho General Hospital

- Bay

- Bay Regional Hospital

- Baidoa Hospital

- Burhakaba Hospital

- Dinsor Hospital

- Filsan Medical Hospital

- Tayo Hospital

- Galguduud

- Abudwak Maternity and Children's Hospital

- Adaado Hospital

- Dusamareb Hospital

- El-Dher District Referral Hospital

- Istalin Hospital

- Gedo

- East Bardera Mothers and Children's Hospital

- Garbahaarey Hospital

- Khalil Hospital

- Luuq Hospital

- West Bardera Maternity Unit

- Hiran

- Dove Voluntary Hospital

- Lower Juba

- Kismayo Hospital

- Mareerey Hospital

- Kismayo Medical Center

- Lower Shebelle

- Afgooye District Hospital

- Belet Hawa Hospital

- Brava Regional Hospital

- Hayat 2 Hospital

- Marka Regional Hospital

- Qoryoley District Hospital

- VMB Maternity Hospital

- Middle Shebelle

- Adale Medical Center

- Jowhar Regional Hospital

- Balcad General Hospital

- Mudug

- Galkayo South Hospital

- Mudug Regional Hospital

- Harardere District Referral Hospital

- Nugal

- Nugal General Hospital

- Sanaag

- Badhan Hospital

- Dhahar Hospital

- Erigavo Referral Hospital

- Las Khorey Hospital

- Sool

- Las Anod Hospital

- Taleh Hospital

- Togdheer

- Burao General Hospital

- Buhoodle District Hospital

- Sheikh Hospital

- Woqooyi Galbeed

- Almedina Multispeciality Hospital

- Arab Medical Union Hospital

- Berbera District Hospital

- Edna Adan Maternity Hospital

- Gabiley District Hospital

- Gargaar Multispeciality Hospital

- Haldoor Hospital

- Hargeisa Canadian Medical Center

- Hargeisa Group Hospital

- Hargeisa Neurology Hospital

- Hargeisa International Hospital

- Kaah Community Hospital

- New Hargeisa Hospital

- Manhal Speciality Hospital

- Masala Specialist Hospital

- M.A.S. Children's Teaching Hospital

- Royal Care Hospital

Medical universities and facilities

edit- Upper Jubba University, Baidoa Somalia Campus, College of Health Science (CHS).

- Amoud University, College of Medicine and Medical Sciences

- Benadir University

- Mustaqbal Universityhttp://mustaqbaluniversity.edu.so/

- University Of Somalia (Uniso)

- University of Southern Somalia

- Abraar University

- University of Health Sciences Bosaaso

- Horn Of Africa University

- New Generation University

- Bay University

- Burao Institute of Health Sciences

- Sool university

- East Africa University

- Edna Adan Maternity Hospital

- Erdoğan Hospital

- Hargeisa Institute of Health Sciences

- Hargeisa University

- Indian Ocean University

- Jazeera University

- Kismayo University

- Livestock university

- Mogadishu Private School of Nursing

- Mogadishu Public School of Nursing

- Mogadishu University

- Nugaal University

- Plasma University

- Puntland School of Nursing

- Somaliland University of Technology

- University of Burao

- University of Hargeisa

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "An Overlooked Consequence of Civil War: Mental Illness in Somalia | Princeton Public Health Review". Archived from the original on 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ^ "Africa: Somalia Ranked Happiest Country in Sub-Saharan Africa - allAfrica.com". Archived from the original on 2016-03-20.

- ^ Rodger, F. C. "Clinical findings, course, and progress of Bietti's corneal degeneration in the Dahlak islands." The British journal of ophthalmology 57.9 (1973): 657.

- ^ Maxamed Siyaad Barre (1970) My country and my people: the collected speeches of Major-General Mohamed Siad Barre, President, the Supreme Revolutionary Council, Somali Democratic Republic, Vol. 3, Ministry of Information and National Guidance, p. 141.

- ^ "Better Off Stateless: Somalia Before and After Government Collapse" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Entrepreneurship and Statelessness: A Natural Experiment in the Making in Somalia". Scribd.com. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "Estimates of Unit Costs for Patient Services for Somalia". Who.int. 6 December 2010. Archived from the original on June 26, 2006. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Somalia". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2016-09-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h UNDP (2001). Human Development Report 2001-Somalia. New York: UNDP.

- ^ a b "UNdata – Somalia". Data.un.org. 20 September 1960. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ in Somalia. "Child health" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2016-09-09.

- ^ WHO. "Child health" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2016-09-09.

- ^ a b c d World Bank and UNDP (2003). Socio-Economic Survey-Somalia-2004. Washington, D.C./New York: UNDP and World Bank.

- ^ World Bank and UNDP (2003). Socio-Economic Survey-Somalia-1999. Washington, D.C./New York: UNDP and World Bank.

- ^ The state of the world´s children 2016 (Report). UNICEF. June 2016. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ "UNFPA Somalia | Renewing the fight against maternal and new-born mortality in Somalia". somalia.unfpa.org. 2016-02-10. Archived from the original on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2016-09-09.

- ^ UNDP (2006). Human Development Report 2006. New York: UNDP.

- ^ "The State Of The World's Midwifery". United Nations Population Fund. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Prevalence of FGM". Who.int. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Rose Oldfield Hayes (1975). "Female genital mutilation, fertility control, women's roles, and the patrilineage in modern Sudan: a functional analysis". American Ethnologist. 2 (4): 617–633. doi:10.1525/ae.1975.2.4.02a00030.

- ^ Herbert L. Bodman, Nayereh Esfahlani Tohidi (1998) Women in Muslim societies: diversity within unity, Lynne Rienner Publishers, p. 41, ISBN 1555875785.

- ^ Suzanne G. Frayser, Thomas J. Whitby (1995) Studies in human sexuality: a selected guide, Libraries Unlimited, p. 257, ISBN 1-56308-131-8.

- ^ Goldenstein, Rachel. "Female Genital Cutting: Nursing Implications". Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 25.1 (2014): 95-101. Web. 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Somalia: Female genital mutilation down". Associated Press via The Jakarta Post. 16 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ "Male Circumcision and AIDS: The Macroeconomic Impact of a Health Crisis by Eric Werker, Amrita Ahuja, and Brian Wendell :: NEUDC 2007 Papers :: Northeast Universities Development Consortium Conference" (PDF). Center for International Development at Harvard University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ a b Ali-Akbar Velayati; Valerii Bakayev; Moslem Bahadori; Seyed-Javad Tabatabaei; Arash Alaei; Amir Farahbood; Mohammad-Reza Masjedi (2007). "Religious and cultural traits in HIV/AIDS epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). Archives of Iranian Medicine. 10 (4): 486–97. PMID 17903054. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2008.

- ^ "Somalia". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. 24 June 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "The Regional Office And Its Partners – Somalia". Emro.who.int. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "SOMALIA PM Said "Cabinet will work tirelessly for the people of Somalia"". Midnimo. 17 January 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Ministry of Health – Puntland State of Somalia Archived 2018-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. Health.puntlandgovt.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-15.

- ^ "Somaliland – Government Ministries". Somalilandgov.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "Somalia aims to provide universal basic health care by 2016". News-Medical. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ a b "JOINT PRESS RELEASE Essential Package of Health Services launched in Somalia to improve maternal and child health". Warbahinta. UNICEF. May 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ "Launch of the Essential Package of Health Services, Mogadishu". British Embassy Mogadishu. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ "Hospital in Somalia" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ "Health Care Delivery in Somalia". Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.