Marysville is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States, part of the Seattle metropolitan area. The city is located 35 miles (56 km) north of Seattle, adjacent to Everett on the north side of the Snohomish River delta. It is the second-largest city in Snohomish County after Everett, with a population of 70,714 at the time of the 2020 U.S. census. As of 2015[update], Marysville was also the fastest-growing city in Washington state, growing at an annual rate of 2.5 percent.

Marysville, Washington | |

|---|---|

Downtown Marysville seen from Interstate 5 | |

|

| |

| Nickname: The Strawberry City | |

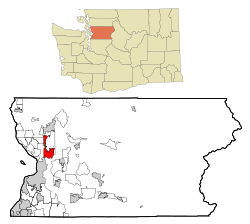

Location of Marysville in Washington state | |

| Coordinates: 48°3′46″N 122°9′48″W / 48.06278°N 122.16333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Snohomish |

| Founded | 1872 |

| Incorporated | March 20, 1891 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Jon Nehring |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21.06 sq mi (54.54 km2) |

| • Land | 20.75 sq mi (53.75 km2) |

| • Water | 0.30 sq mi (0.79 km2) |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 70,714 |

| • Estimate (2022)[3] | 72,275 |

| • Rank | US: 532nd |

| • Density | 3,387.37/sq mi (1,307.85/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 98270–98271 |

| Area code | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-43955 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512435[4] |

| Website | marysvillewa.gov |

Marysville was established in 1872 as a trading post by James P. Comeford, but was not populated by other settlers until 1883. After the town was platted in 1885, a period of growth brought new buildings and industries to Marysville. In 1891, Marysville was incorporated and welcomed the completed Great Northern Railway. Historically, the area has subsisted on lumber and agrarian products; the growth of strawberry fields in Marysville led to the city being nicknamed the "Strawberry City" in the 1920s.

The city experienced its first wave of suburbanization in the 1970s and 1980s, resulting in the development of new housing and commercial areas. Between 1980 and 2000, the population of Marysville increased five-fold. In the early 2000s, annexations of unincorporated areas to the north and east expanded the city to over 20 square miles (52 km2) and brought the population over 60,000.

Marysville is oriented north–south along Interstate 5, bordering the Tulalip Indian Reservation to the west, and State Route 9 to the east. Mount Pilchuck, whose 5,300-foot-high (1,600 m) peak can be seen from various points in the city, appears in the city's flag and seal.

History

editFoundation and early history

editMarysville was established in 1872 by government-appointed Indian agent James P. Comeford, an Irish immigrant who had served in the Civil War, and his wife Maria as a trading post on the Tulalip Indian Reservation. The reservation, located to the west of modern-day Marysville, was established by the Point Elliot Treaty of 1855, signed by local Native American tribes and territorial governor Isaac Stevens at modern-day Mukilteo. The treaty's signing opened most of Snohomish County to American settlement and commercial activities, including logging, fishing and trapping.[5][6]

The timber industry was the largest active industry in the area during the 1860s and 1870s, with hillsides in modern-day Marysville cleared by loggers for dairy farms. The Comefords' trading post accepted business from the reservation and logging camps that were established near the mouth of the Snohomish River. In 1874, Comeford acquired three timber claims from local loggers for $450, totaling 1,280 acres (5.2 km2), and cleared the land in preparation for settlement. Comeford and his wife moved to the present site of Marysville in 1877, building a new store and wharf.[5] Although Marysville remained a one-man town until 1883, a post office and school district were both established by 1879 using the names and signatures of Native American neighbors of Comeford's, who were given "Boston" names for the petition. Comeford completed construction of a two-story hotel in 1883 to welcome new settlers from outside the region.[7][8][9]

The origin of the settlement's name, Marysville, remains disputed.[5][10] According to the Marysville Historical Society, it was to be named Mariasville for Maria Comeford, but was changed to Marysville after the postal department identified a similarly-named town in Idaho.[11] Among the first residents to arrive in the area in the 1880s were James Johnson and Thomas Lloyd, who allegedly suggested that the town be named for their previous home of Marysville, California.[6][12] Comeford sold his store and wharf to settlers Mark Swinnerton and Henry B. Myers in 1884, and moved north to the Kellogg Marsh (now part of Marysville) to farm 540 acres (220 ha) of land he purchased.[7]

Marysville was formally platted on February 25, 1885, filed by the town physician J. D. Morris and dedicated by the Comefords.[7] More settlers began to arrive after the completion of the town's first sawmill in 1887, joined by three others by the end of the decade.[5] Marysville was officially incorporated as a fourth-class city on March 20, 1891, with a population of approximately 400 residents and Mark Swinnerton serving as the city's first mayor.[6] The Great Northern Railway also completed construction of its tracks through Marysville in 1891, building a drawbridge over Ebey Slough and serving the city's sawmills.[13] A newspaper named the Marysville Globe was established by Thomas P. Hopp in 1892 and continues to be published in the city.[5]

Early 20th century

editBy the turn of the century, the city's population had grown to 728, and social organizations began to establish themselves in Marysville, including a lodge of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows and a Crystal Lodge of the Free and Accepted Masons. The first city hall was opened in late 1901, at a cost of $2,000;[14] the building also housed the city's fire department, and later the first public library in 1907. Electrical and water supply systems were both inaugurated in 1906, alongside the construction of a high school building.[5]

The timber industry in Marysville peaked in 1910, at which point the city's population reached 1,239, with 10 sawmills producing lumber on the shores of Ebey Slough. Agriculture began to grow in Marysville, with its fertile land suited for the growing of strawberries in particular. By 1920, the city had more than 2,000 acres (810 ha) of strawberry fields, leading to the coining of the city's nickname of "Strawberry City" and the establishment of the annual Strawberry Festival in 1932.[5][15]

An automobile bridge across Ebey Slough and the Snohomish River estuary to Everett was completed in 1927, with funding from the state department of highways to complete the Pacific Highway (later part of U.S. Route 99, and present-day State Route 529).[16][17] The city remained relatively unchanged through the Great Depression, with the diversity of industries credited for Marysville avoiding the worst of economic hardship experienced by other nearby communities.[5] During World War II, an ammunition depot was built on the Tulalip Reservation near present-day Quil Ceda, later being re-used as a Boeing test site after the aerospace company expanded in Everett.[18]

Late 20th century

editMarysville began to grow into a bedroom community of Seattle and Everett in the late 1950s, spurred by the completion of Interstate 5 in stages from 1954 to 1969.[19][20] The new freeway bypassed the town, causing a minor decline in tourist revenue at businesses that later rebounded to previous levels, also eliminating a major traffic bottleneck that paralyzed the city's downtown.[21][22] The city annexed its first area outside its original city limits in 1954, growing to over 2,500 residents.[18] Marysville was re-classified as a third-class city in March 1962 and the local Chamber of Commerce boosted the city during the Century 21 Exposition held in nearby Seattle, hosting a UFO exposition in Smokey Point that summer.[23][24]

On June 6, 1969, a freight train operated by Great Northern rammed into several disconnected train cars in front of the Marysville depot, destroying the building, killing two men in an engine on a nearby siding and injuring two others. The crash, blamed on the engineer failing to adhere to the track's speed limit, caused $1 million in damage to railroad property and resulted in the demolition of the depot, which had served the city since 1891 and was not rebuilt.[25][26]

After the initial wave of suburbanization, which built homes in former strawberry fields to the north and east of Marysville, the city's population totaled 5,544 in 1980.[5] The city's growth was concentrated in outlying areas, leaving downtown to weaken economically. In 1981, the Marysville City Council declared that the downtown area was "blighted" and in need of a facelift. The council presented a $30 million urban renewal plan in November 1982 that would add new retail and office space, mixed-use development, public parks and improve pedestrian conditions in downtown, along with a large public parking lot and an expanded public marina.[27] The plan was opposed by the marina's owner and other downtown property owners and produced lengthy public hearings that lasted until the following year.[28][29] Mayor Daryl Brennick vetoed the plan in June 1983, citing public outcry and the high cost of the proposal, and the city council failed to overturn the decision.[30] The city instead developed a downtown shopping mall that involved the demolition of a water tower (one of two in the city) and several historic buildings in 1987.[31] The $17 million mall opened in August 1988 with 24 stores and 180,000 square feet (17,000 m2) of retail space.[32]

Marysville underwent further population changes in the late 1980s and 1990s, continuing to build more housing and new retail centers after the lifting of a building moratorium.[33][34] The city continued to annex outlying areas, growing to a size of 9.8 square miles (25 km2) and population of 25,315 by 2000.[5] Marysville also saw a thrice-fold increase in the number of businesses from 1991 to 1996 and was close to eclipsing Edmonds in retail sales.[35] The decade also saw the construction of new schools, a YMCA facility, a library, and a renovated senior center at Comeford Park.[36] The Tulalip Tribes opened its first casino in 1992, the second Indian casino in the state, and began development of a large shopping mall at Quil Ceda Village in the early 2000s.[37]

Marysville attempted to attract regional facilities in the late 1990s and 2000s, with varying degrees of success. The U.S. Navy opened Naval Station Everett in Everett in 1994, which was accompanied by a support annex in northern Marysville near Smokey Point the following year.[38] The Puget Sound Regional Council explored the expansion of Arlington Municipal Airport into a regional airport in the 1990s to relieve Seattle–Tacoma International Airport,[39] but decided instead to build a third runway at Sea-Tac because of existing traffic and local opposition.[40][41] In September 2004, Marysville won a bid to build a 850-acre (340 ha) NASCAR racetrack (to be operated by the International Speedway Corporation) near Smokey Point.[42] The project was cancelled two months later after concerns about traffic impacts, environmental conditions, and $70 million in required transportation improvements arose.[43] The NASCAR site was later pitched as a candidate for a new University of Washington satellite campus (known as UW North Sound) in the late 2000s,[44] competing with a site in downtown Everett.[45] The project was put on hold in 2008 after continued disagreements over the campus's location, before being cancelled entirely in 2011, replaced by a new Washington State University branch campus in Everett.[46][47]

21st century

editFrom 2000 to 2006, the city annexed 23 additional areas, totaling 1,416 acres (573 ha), lengthening the city to border Arlington at Smokey Point.[48][49] The largest single annexation came in 2009, with Marysville absorbing 20,000 residents and 2,847 acres (1,152 ha) from North Marysville, an unincorporated area that comprised the majority of the urban growth area.[50] New retail centers in North Lakewood and at 116th Street were built in 2007, leading to increased sales tax revenue for the city and increased traffic congestion in areas of the city.[51]

The opening of the city's waterfront park and public boat launch in 2005 spurred interest in redevelopment of downtown Marysville.[52] The closure of the final waterfront sawmill in 2005, followed by its acquisition and demolition by the city in 2008, led city planners to propose a downtown master plan.[53] The 20-year plan, released and adopted by the City Council in 2009, proposed the redevelopment of the Marysville Towne Center Mall into a mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented area with a restored street grid. The waterfront area would include trails, residential buildings, and retail spaces, along with a new city hall and civic center.[54][55] The city government acquired several parcels in the waterfront in the 2010s with the intent of partnering with a private developer.[56] In 2015, the city of Marysville was also the recipient of grants and consultation from the Environmental Protection Agency's smart growth program, identifying strategies for infill development in downtown.[57]

By 2010, Marysville had grown to a population of 60,020 and surpassed Lynnwood and Edmonds to become the second-largest city in Snohomish County.[58]: 3 [59] In 2015, the city grew at a rate of 2.5 percent, the largest rate of any city in Washington state.[60] New housing and industrial areas are under construction and planned to fuel further population growth in Marysville.[61] The city's school district opened a second high school, Marysville Getchell, in 2010 to serve students living in the eastern area of Marysville. The school previously consisted of four Small Learning Communities which share the same campus and athletics programs.[62] On October 24, 2014, the cafeteria of Marysville Pilchuck High School was the site of a school shooting, in which five students (including the perpetrator) were killed and another was left seriously injured.[63] The shooting garnered national attention amidst a debate about gun violence and gun restrictions.[64][65] The cafeteria was closed for the rest of the school year and replaced by a new building opened in January 2017, funded by $8.3 million from the state legislature and school district.[66]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau's 2010 census, Marysville has a total area of 20.94 square miles (54.2 km2)—20.68 square miles (53.6 km2) of land and 0.26 square miles (0.67 km2) of water.[67] The city is located in the northwestern part of Snohomish County in Western Washington,[68] approximately 35 miles (56 km) north of Seattle.[58]: 3 Marysville's city limits are generally bound to the south by Ebey Slough (part of the Snohomish River delta) and Soper Hill Road, to the west by Interstate 5 and the Tulalip Indian Reservation, to the north by the city of Arlington, and to the east by the Centennial Trail and State Route 9.[69] The city's urban growth boundary includes 158 acres (64 ha) outside of city limits, bringing the total area to 21.14 square miles (54.8 km2).[70]: 3–4

The city's topography varies from the low-lying downtown, located along the banks of Ebey Slough 5 feet (1.5 m) above sea level, rising to 160 feet (49 m) near Smokey Point and over 465 feet (142 m) in the eastern highlands.[71]: 2–1 Marysville sits in the watershed of two major creeks, Quilceda Creek and Allen Creek, and approximately 70 minor streams that flow into Ebey Slough and Snohomish River.[72]: 3 During the early 20th century, repeated controlled flooding and other engineering works in the Snohomish River delta contributed to the replenishment of the area's fertile silty soil for use in farming.[73]

The Marysville skyline is dominated by views of Mount Pilchuck and the Cascade Mountains to the east and the Olympic Mountains to the west.[71]: 2–1 [74] The 5,324-foot (1,623 m) Mount Pilchuck appears on the city's logo and flag,[75] and is the namesake of the Marysville Pilchuck High School.[76]

The City of Marysville's comprehensive plan defines 11 general neighborhoods within the city and its urban growth boundary: Downtown, Jennings Park, Sunnyside, East Sunnyside/Whiskey Ridge, Cedarcrest/Getchell Hill, North Marysville/Pinewood, Kellogg Marsh, Marshall/Kruse, Shoultes, Smokey Point, and Lakewood.[77]: 4–7

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 262 | — | |

| 1900 | 728 | 177.9% | |

| 1910 | 1,239 | 70.2% | |

| 1920 | 1,244 | 0.4% | |

| 1930 | 1,354 | 8.8% | |

| 1940 | 1,748 | 29.1% | |

| 1950 | 2,259 | 29.2% | |

| 1960 | 3,117 | 38.0% | |

| 1970 | 4,343 | 39.3% | |

| 1980 | 5,080 | 17.0% | |

| 1990 | 10,328 | 103.3% | |

| 2000 | 25,315 | 145.1% | |

| 2010 | 60,020 | 137.1% | |

| 2020 | 70,714 | 17.8% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 72,275 | [3] | 2.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[78] | |||

Until the post-World War II population boom of the 1950s, Marysville's population never rose above 2,000 residents, who were all located within the original city limits. The city began annexing surrounding areas in the 1950s, anticipating suburban development that would replace existing farmland and forest lands. From 1950 to 1980, the city doubled in population, growing to over 5,000 residents, with an additional 15,000 residents in surrounding areas.[78][79] Marysville's population grew five-fold between 1980 and 2000, increasing to 25,000 through natural growth and annexation of developed areas.[5]

From 2000 to 2010, the city's population increased to over 60,000 after the annexation of the urban growth area and continued development, making Marysville the second-largest city in Snohomish County behind Everett.[58]: 3 In 2015, Marysville was the fastest-growing city in Washington, growing at a rate of 2.5 percent to an estimated population of 66,773.[80] As of 2016[update], Marysville is the 17th largest city in Washington.[59] The United States Census Bureau designates Marysville and the surrounding cities of Arlington, Lake Stevens, and Snohomish as a continuous urbanized area, with a population of 145,140 as of 2010[update].[81]

As of the 2020 census, Marysville has a population of 70,714 residents. The 2022 American Community Survey estimates that the median household income in the city is $104,433 and 65 percent of residents are employed.[2]

2010 census

editAs of the 2010 census, there were 60,020 people, 21,219 households, and 15,370 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,902.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,120.6/km2). There were 22,363 housing units at an average density of 1,081.4 per square mile (417.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 80.0% White, 1.9% African American, 1.9% Native American, 5.6% Asian, 0.6% Pacific Islander, 4.4% from other races, and 5.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 10.3% of the population.[82]

There were 21,219 households, of which 40.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.8% were married couples living together, 12.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 27.6% were non-families. 20.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.80 and the average family size was 3.22.[82]

The median age in the city was 34.2 years. 27.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28.8% were from 25 to 44; 24.7% were from 45 to 64; and 9.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.4% male and 50.6% female.[82]

2000 census

editAs of the 2000 census, there were 25,315 people, 9,400 households, and 6,608 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,640.1 people per square mile (1,019.2/km2). There were 9,730 housing units at an average density of 1,014.7 per square mile (391.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.21% White, 1.02% African American, 1.60% Native American, 3.82% Asian, 0.36% Pacific Islander, 1.89% from other races, and 3.10% from two or more races. Hispanic Latino of any race were 4.83% of the population.[83]

There were 9,400 households, out of which 40.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.1% were married couples living together, 11.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.7% were non-families. 23.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.15.[83]

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 30.1% under the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 32.9% from 25 to 44, 17.7% from 45 to 64, and 11.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.6 males.[83]

The median income for a household in the city was $47,088, and the median income for a family was $55,796. Males had a median income of $42,391 versus $30,185 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,414. About 3.7% of families and 5.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.0% of those under age 18 and 5.9% of those age 65 or over.[83]

Economy

edit| Employer | Employees |

|---|---|

| 1. Marysville School District | 1,356 |

| 2. C&D Zodiac | 670 |

| 3. Walmart | 295 |

| 4. City of Marysville | 266 |

| 5. Fred Meyer | 207 |

| 6. The Everett Clinic | 172 |

| 7. Marysville Care Center | 162 |

| 8. Target | 157 |

| 9. WinCo Foods | 145 |

| 10. Costco | 325 |

Marysville has an estimated 33,545 residents who are in the workforce, either employed or unemployed.[84] Only 10 percent of residents work within Marysville city limits, with the majority commuting south to employers in Everett, Downtown Seattle and the Eastside, including Boeing, Naval Station Everett, Amazon, and Microsoft.[85] The average one-way commute is approximately 30 minutes; 79 percent of workers drive alone to their workplace, while 12 percent carpool and 3 percent used public transit.[84]

Marysville's economy historically relied on lumber production and agriculture, including the cultivation of strawberries, hay and oats.[5] During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Marysville was not adversely impacted unlike other cities in the county and country because of its diverse industries, including sawmills, grain mills, a tannery, a fertilizer plant, and a berry packing plant.[5] The city's largest employer in the early 1950s, the Weiser Lumber Company, was destroyed in a fire on May 6, 1955, causing $300,000 in damage.[86] The lumber mill at the site was later acquired by Welco Lumber, who closed the plant in 2007.[87]

Suburban development and the rise of long-distance commuting in the 1950s led Marysville to transition toward a service-based economy.[88] One of the largest employers of Marysville residents is the Boeing Company and their Everett assembly plant.[89] While farms still operate in the area around the city, since 1980 the lumber industry has all but ceased and is no longer a major factor in the local economy.[90] Since the late 1980s, the economy of Marysville has centered around retail areas,[88] including the downtown Marysville Towne Center Mall (opened in 1987)[31] and the Naval Support Complex (opened in 1995).[38] The Tulalip Tribes built a new casino and new shopping center in the early 2000s to the west of Marysville, contributing to a fall in sales tax revenue.[37][48][91] In the latter half of the decade, Marysville opened two large retail centers of its own in the annexed Lakewood neighborhood and at 116th Street NE, bringing additional jobs and sales tax revenue to the city.[51][92] An auto row along Smokey Point Boulevard in northern Marysville was developed in the late 2010s and is home to several car dealerships.[93][94]

Marysville is also home to a small manufacturing industry based in the northern part of the city near Smokey Point and Arlington's manufacturing center at Arlington Municipal Airport. The cities of Arlington and Marysville lobbied for the creation of the Cascade Industrial Center from the Puget Sound Regional Council, which was approved in 2019.[95] The industrial area is planned to encompass 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of land between the two cities and support 25,000 jobs by 2040;[96] its first buildings for Amazon, Blue Origin, and other companies were opened in 2022.[97] The city's second-largest employer is C&D Zodiac, an aerospace parts manufacturer tied to Boeing, with 670 employees at an office in northern Marysville.[98] In 2016, outdoor footwear manufacturer Northside USA opened a new headquarters at a 110,000-square-foot (10,000 m2) warehouse in northern Marysville.[99]

Government and politics

editMarysville, a non-charter code city, operates under a mayor–council government with an elected mayor and an elected city council.[100] The mayor serves a term of four years and has been a full-time position since July 1997.[101][102] A proposal to change to a council–manager government was submitted as a ballot measure in 2002 and rejected by voters.[103][104] The 32nd and current mayor of Marysville, Jon Nehring, was appointed on June 28, 2010, after the resignation of incumbent Dennis Kendall;[105] Nehring was elected to a full term in November 2011, and re-elected in 2015, 2019, and 2023;[106][107] he ran unopposed in 2023.[108]

The city council is composed of seven residents who are elected in at-large, non-partisan elections to four-year terms. The elections are staggered, with three positions elected on the same ballot as the mayor, and four positions elected two years later. The council also selects a member to serve as council president for a one-year term.[101] The council meets twice per month, excluding holidays and during the month of August, in the City Council Chambers at the city hall.[109] A proposal to adopt a council–manager government system was defeated by voters in 2002.[110]

According to the Washington State Auditor, Marysville's municipal government employs 266 people and its general fund expenditures totaled $38.7 million in 2015.[111] The 2015–16 biennial budget allocated $128.1 million in expenditures for 2015 and $109.7 million for 2016; general fund spending was limited to $44.1 million in 2015 and $45.1 million.[112] City taxes, collected from retail sales, property assessment, and other sources, accounted for $34.3 million in annual revenue.[113] As of 2024[update], the combined sales tax rate in Marysville is 9.4 percent, of which 1.3 percent is collected by the city government and its associated transportation benefit district.[114]

The city has several departments providing services to its residents, including a police department, municipal courts, garbage collection, planning and zoning, parks and recreational programs, engineering, street maintenance, water and wastewater services, and stormwater treatment.[58]: 4 A new civic campus, combining a police station, city jail, and city hall,[115] was built adjacent to Comeford Park in downtown and opened in October 2022.[116][117] Marysville contracts with regional districts for other services, including a public library,[118] public transport,[119] electricity,[120] natural gas,[121] and fire protection.[122]

At the federal level, Marysville has been part of the 1st congressional district, represented by Democrat Suzan DelBene, since 2022. The district encompasses parts of Snohomish and King counties between Arlington and Bellevue that generally lie east of Interstate 5.[123][124] The city lies within two state legislative districts, each with a state senator and two state representatives: the 38th district includes most of the city's southern side along with the Tulalip Indian Reservation and the city of Everett; the 39th district includes the northwestern part of the city and the city of Arlington; and the 44th district includes the southeastern part of the city and the outlying areas of eastern Snohomish and Skagit counties.[125][126] Marysville is wholly part of the Snohomish County Council's 1st district, which represents most of northern Snohomish County.[127]

Culture

editThe Red Curtain Foundation for the Arts was founded in 2009 to offer art, music and theatre classes in Marysville, including the staging of community theatre productions. The Red Curtain renovated a former lumber store in 2012 to house a community arts center,[128] but moved in 2015 to a new location at a shopping center in central Marysville in 2015, which will be renovated into a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) arts center with a 130-seat theatre, classrooms, and other amenities.[129][130] Other local arts organizations include the Marysville Arts Coalition,[131] and the Sonus Boreal women's choir.[132]

Marysville was formerly home to a children's museum from 1993 to 1995, located at the Marysville Towne Center Mall.[133] The museum relocated to a temporary space in Everett before opening a permanent downtown Everett location in 2004 as the Imagine Children's Museum.[134][135] The city also hosts a historic telephone museum located in downtown since 1996.[136]

The 1980 made for TV movie Trouble in High Timber Country was filmed in Marysville.[137]

Parks and recreation

editThe City of Marysville operates and maintains 487.4 acres (197.2 ha) on 35 public recreational facilities within city limits,[77]: 9–6 including parks, playgrounds, sports fields, nature preserves, community centers, a golf course and other facilities.[77]: 9–10

Comeford Park, located in downtown Marysville and named for town founders James P. Comeford and his wife Maria, is the city's oldest municipal park[77]: 4–82 and is home to the city's landmark water tower, built in 1921 and non-functional since the 1970s. The 120-foot-tall (37 m) water tower, originally accompanied by a second tower demolished in 1987, was planned in the late 1990s to be demolished,[138] but was saved in 2002 after $500,000 was raised by the Marysville Historical Society to renovate and preserve the structure.[139] The 2.1-acre (0.85 ha) Comeford Park is also home to a gazebo donated by the city's Rotary Club, a children's playground, and a spray park that opened in 2014.[77]: 9–27 [140][141]

Jennings Park, located to the east of downtown Marysville on Armar Road, is considered the centerpiece of the city's park system. The 53-acre (21 ha) park includes play areas, experimental gardens and composting sites, sports fields, a nature walking trail, a preserved barn, and historical exhibits. It is also home to the Park and Recreation Department's administrative offices.[77]: 9–36 The park opened in 1963 on land donated by the Jennings family.[142]

Other major parks in Marysville include the Ebey Waterfront Park and boat launch opened in 2005,[52] and a skate park opened in 2002.[77]: 4–82 The city also maintains the Cedarcrest Golf Course in eastern Marysville, an 18-hole, 99.4-acre (40.2 ha) municipal golf course that was established in 1927 and was acquired by the city in 1972.[77]: 9–34 Marysville is also home to private, non-profit recreation facilities operated by the YMCA and Boys and Girls Club, as well as a privately owned bowling alley and indoor roller skating rink.[77]: 9–52

The Marysville Parks and Recreation Department also organizes youth sports leagues for basketball and soccer. The department uses facilities leased from the Marysville School District,[77]: 9–52 as well as purpose-built areas like the Strawberry Fields Athletic Complex in northern Marysville, a 71-acre (29 ha) park for soccer and disc golf.[77]: 9–39

Events

editMarysville holds an annual strawberry festival in the third week of June, which is highlighted by a grand parade on State Avenue and a nighttime fireworks show.[143] The first annual strawberry festival was held in 1932 to celebrate the city's strawberry growing industry, and has only been cancelled during World War II from 1942 to 1945 and a polio outbreak in 1949.[5][144] The week-long event attracts over 100,000 visitors and is the largest strawberry festival in Washington state.[145] In addition to the Marysville Strawberry Festival, the city holds other annual events, including the Merrysville for the Holidays celebration and grand parade in early December.[146]

The city re-established a farmer's market in 2015, initially in the old city hall's parking lot on State Avenue. The farmer's market was open weekly on Saturdays from July to October and operated by the Allen Creek Community Church.[147][148] The event moved to 3rd Street in downtown Marysville in June 2023.[149]

Media

editThe Marysville Globe, a weekly newspaper, is based in Marysville and serves northern Snohomish County.[150] The Globe, published since 1891 and owned by Sound Publishing alongside The Arlington Times, began delivering free newspapers to all Marysville residents on November 28, 2007;[151][152] both papers suspended publication in March 2020 in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[153] The North County Outlook was published weekly from September 2007 to October 2022.[154]

The Herald in Everett serves the entire county, including Marysville, and prints daily editions.[155] Marysville is also part of the Seattle–Tacoma media market, and is served by Seattle-based media outlets including The Seattle Times;[156] broadcast television stations KOMO-TV, KING-TV, KIRO-TV, and KCPQ-TV; and various radio stations. Cable television service in Marysville is provided by Comcast and Ziply Fiber (formerly Frontier Communications)[157] for most of the city and Wave Broadband in North Lakewood; the city also owns a public-access television station that is operated by the Marysville School District.[158][159]

Marysville's public library is part of the Sno-Isle Libraries system, which operates libraries in Island and Snohomish counties; it was annexed into the system in 1968.[160] The library is based in a 23,000-square-foot (2,100 m2) building located on Grove Street that opened on July 27, 1995, to replace a 4,000-square-foot (370 m2) building on the same street that opened in 1978.[160][161] Recent population growth in northern Marysville near Smokey Point and Lakewood have led to the establishment of a pilot library in the area in 2018, and a recommendation to Sno-Isle to build a permanent branch by 2025.[162][163]

Historical preservation

editThe Marysville Historical Society was formed in 1974 as a non-profit organization to preserve the history of Marysville and its surrounding area.[164][165] The society began planning the construction of a museum at Jennings Park in 1986, but was unable to raise enough funds to begin construction until 2012.[165] The museum opened on March 19, 2016, coinciding with the 125th anniversary of the city's incorporation, using donated funds to finish construction.[166]

The Marysville and Tulalip area have several properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).[167] The Marysville Opera House was built by the Independent Order of Oddfellows in 1911 at a cost of $20,000; it would later be listed in 1982 and renovated in 2003 for use by city events.[168] On the Tulalip reservation, the Indian Shaker Church and St. Anne's Roman Catholic Church were built in the early 20th century and listed on the register in 1976; the Tulalip Indian Agency Office, built in 1912, was listed for its significance in tribal affairs as well as the town's founding.[167] Another historic landmark in the area, not listed on the register, is the Gehl House at Jennings Park, a pioneer-era wooden cabin built in 1889 and restored with original furnishings.[169]

Sister city

editMarysville initiated its first sister city relationship in 2017 with Yueqing, a coastal city in the Chinese province of Zhejiang. The two cities have exchanged visits by officials, including tours of manufacturing areas and infrastructure projects.[170]

Notable residents

editNotable people from Marysville include:

- Brady Ballew, soccer player[171]

- Robert A. Brady, economist[172]

- Larry Christenson, baseball player[173]

- Trina Davis, soccer player representing Fiji[174]

- John DeCaro, hockey player[175]

- Jan Haag, writer, artist, poet and filmmaker[176]

- Charles Hamel, oil industry whistle-blower[177]

- Jake Luton, American football player[178]

- Jack Metcalf, U.S. representative from Washington's 2nd congressional district[179]

- Howell Oakdeane Morrison, musician, dance instructor, and entrepreneur, founder of Seattle-based Morrison Records[180]

- Steve Musseau, American football coach[181]

- Haley Nemra, track athlete[182]

- Jeff Pahukoa, American football player[183]

- Shane Pahukoa, American football player[173]

- Jarred Rome, discus thrower[184]

- Patty Schemel, musician with Hole and other bands[185]

- Steve Thompson, American football player[186]

- Emily Wicks, state representative[187]

- Simeon R. Wilson, state politician and newspaper editor[188]

Education

editPublic schools in Marysville are operated by the Marysville School District, which covers most of the incorporated city and the Tulalip Indian Reservation. The district had an enrollment of approximately 10,804 students in 2013 and has 23 total schools, including two high schools (Marysville Pilchuck and Marysville Getchell), four middle schools, eleven elementary schools, and several alternative learning facilities.[189] The school district was the site of the then-longest teacher strike in Washington state history in 2003, lasting for 49 days until the Snohomish County Superior Court declared the strike illegal.[190]

Other portions of the city are served by the Arlington School District, Lake Stevens School District, and Lakewood School District.[77]: 11–9 [191] Marysville also has one private school, Grace Academy, which was established as a Christian school in 1977 and enrolls 330 students.[192]

Marysville is located near the Everett Community College, the north county region's only post-secondary education institution, situated in north Everett. The college moved its cosmetology school to Marysville in 1996, offering classes and accreditation for students as well as public salon services.[193][194]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editMarysville is located along the east side of Interstate 5 (I-5), which connects the city to Vancouver, British Columbia to the north and Seattle to the south. The freeway has four exits serving Marysville, located at 4th Street in Downtown, 88th Street NE near Quil Ceda Village, 116th Street NE near Kruse Junction, and 172nd Street NE near Smokey Point. Several state highways also run within Marysville city limits, including State Route 9, State Route 528 (4th Street and 64th Street), State Route 529 (State Avenue), and State Route 531 (172nd Street NE).[195] The city's primary north–south arterial street, State Avenue, was formerly part of U.S. Route 99 and has been widened and improved in segments since 2000. Other major streets include 51st Avenue NE, 67th Avenue NE, Grove Street, and Sunnyside Boulevard.[77]: 8–4 [196]

Marysville ranks eighth among Washington cities for longest commute times, with an average commute of approximately 30 minutes.[84][197] The state government began construction in 2023 on a northbound high-occupancy vehicle lane on I-5 and a new interchange at State Route 529 south of downtown to alleviate congestion on east–west railroad crossings in the city.[198][199] On April 22, 2014, Marysville voters approved the creation of a city transportation benefit district and a 0.2 percent sales tax to fund transportation improvements in the city, including road repairs, bicycle and pedestrian access, and new capital projects.[200]

Public transportation in Marysville and Snohomish County is provided by Community Transit. The agency operates all-day local bus service in Marysville on four routes, connecting to Smokey Point, the Tulalip Indian Reservation, Lake Stevens, Everett and Lynnwood. Community Transit also operates five commuter express routes during peak hours from park and ride facilities in Marysville to the Boeing Everett Factory, Downtown Seattle and the University of Washington campus.[201] Marysville is one of the largest cities in the metro area excluded from the Sound Transit regional service area,[202] but expressed interest in joining the regional transit authority in the 1990s.[203][204] The city plans to receive Swift Bus Rapid Transit service from Community Transit by 2028,[205] and has been listed as a candidate for future Sounder commuter rail and Link light rail service.[206]

Marysville is bisected by a north–south railroad operated by BNSF Railway, carrying freight as well as Amtrak Cascades passenger trains that do not stop in Marysville.[207] The nearest passenger rail station is located in Everett, also served by Greyhound intercity bus service,[208] although there are plans from the Tulalip Tribes to build a train station at NE 116th Street in Marysville.[209] The railroad, which includes a spur line to serve Arlington, has 23 total level crossings in Marysville that cause traffic congestion on intersecting streets.[207][210] The nearest municipal airports to Marysville are Arlington Municipal Airport and Paine Field in Everett, while the nearest international airport is Seattle–Tacoma International Airport, 45 miles (72 km) to the south.[211] A private airport and housing development, Frontier Airpark, is located between Marysville and Granite Falls.[212]

Marysville is bisected by the Centennial Trail, a multi-use trail running along the eastern part of the city near State Route 9 between Snohomish and Arlington.[213] The city also has plans to build a 30-mile (48 km) network of trails,[214] including the partially-completed Ebey Slough waterfront trail,[215] under transmission lines in eastern Marysville,[216] and in the Lakewood area.[217]

Utilities

editElectric power in Marysville is provided by the Snohomish County Public Utility District (PUD), a consumer-owned public utility that sources most of its electricity from the federal Bonneville Power Administration (BPA).[218][219] The BPA operates the region's system of electrical transmission lines, including Path 3, a major national transmission corridor running along the eastern side of Marysville towards British Columbia.[220][221] Puget Sound Energy provides natural gas to Marysville residents and businesses;[121] two major north–south gas pipelines run through eastern Marysville and are maintained by the Olympic Pipeline Company, a subsidiary of BP,[222] and the Northwest Pipeline Company, a subsidiary of Williams Companies.[223][224]

The City of Marysville provides municipal solid waste collection and disposal services,[225] while contracting Waste Management for mandatory single-stream recycling and optional yard waste disposal.[226] The municipal government also provides water and wastewater treatment to residents and businesses within city limits and in the surrounding area. Marysville's water system is granted water rights for up to 20.71 million US gallons per day (907,000 L/ks), sourced from the Stillaguamish River, Spada Lake, and a well at Edward Springs near Lake Goodwin.[227][228] The water system includes several pumping stations and over 297.6 miles (478.9 km) of water pipes.[70]: 1–2 Marysville's wastewater system empties into a wastewater treatment plant south of the city with a daily capacity of 20,143 pounds per day (105.75 kg/ks). The city has 210 miles (340 km) of sewage pipeline and 15 pump stations.[229] Stormwater treatment is also handled by the municipal Public Works Department and consists of 185 miles (298 km) of storm lines, 11,914 storm drains, and 346 detention ponds.[71]: 2–25 The city built a 7-acre (2.8 ha) regional stormwater treatment plant in 2003 and took control of local treatment in 2007.[71]: 2–25 [72]: 5

Areas annexed into the city of Marysville are transferred to municipal water and waste services through agreements between the city and the Snohomish County PUD.[230]

Health care

editMarysville does not have a general hospital, but is located near the Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett and Cascade Valley Hospital in Arlington.[231] The city has several community clinics, including two operated by The Everett Clinic and one operated by Providence.[232][233] A clinic operated by Kaiser Permanente is planned to open in Smokey Point in 2020.[234] A $22 million psychiatric hospital in Smokey Point with 115 beds opened in June 2017.[235][236]

References

edit- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Census Bureau Profile: Marysville city, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Washington: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. May 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Marysville, Washington". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dougherty, Phil (July 26, 2007). "Marysville — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c Hastie, Thomas P.; Batey, David; Sisson, E.A.; Graham, Albert L., eds. (1906). "Chapter VI: Cities and Towns". An Illustrated History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties. Chicago: Interstate Publishing Company. pp. 345–349. LCCN 06030900. OCLC 11299996. Retrieved January 24, 2017 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Dougherty, Phil (October 5, 2007). "Comeford, James Purcell (1833–1909)". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Comeford, T. F. (November 1908). Wilhelm, Honor L. (ed.). "Marysville, Washington". The Coast. XVI (5). Seattle: The Coast Publishing Company: 329–332. OCLC 81457448. Retrieved March 18, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hunt, Herbert; Kaylor, Floyd C. (1917). Washington, West of the Cascades: Historical and Descriptive. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 395. OCLC 10086413. Retrieved April 10, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Banel, Feliks (September 6, 2019). "All Over The Map: Marysville named for a cannibal?". KIRO Radio. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Powell, Steve (May 22, 2018). "Museum turns 1, exhibits much older than that". Marysville Globe. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Meany, Edmond S. (1923). Origin of Washington Geographic Names (PDF). University of Washington Press. p. 160. OCLC 1963675. Retrieved January 24, 2017 – via Oregon State University Libraries.

- ^ Semple, Eugene (October 10, 1891). "Appendix". First Report of the Harbor Line Commission of the State of Washington. Olympia, Washington: O. C. White, State Printer. p. 115. OCLC 41141497. Retrieved January 24, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Washington's Prosperity: Marysville". The Seattle Times. October 19, 1901. p. 27.

- ^ "Strawberries take spotlight in Marysville". The Seattle Times. June 14, 1939. p. 11.

- ^ Caldbick, John (March 23, 2012). "Ebey Slough Bridge (1925–2012)". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Coe, Ellis (August 21, 1927). "Two cities join in celebrating highway cut-off". The Seattle Times. p. D1.

- ^ a b Marysville Community Development Department (April 2005). "Chapter II. Vision – Marysville: Past, Present and Future" (PDF). City of Marysville Comprehensive Plan (Report). City of Marysville. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ Patty, Stanton (October 31, 1954). "Highway section opens". The Seattle Times. p. 22.

- ^ Dougherty, Phil (April 10, 2010). "Interstate 5 is completed in Washington on May 14, 1969". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Patty, Stanton (January 14, 1956). "Marysville prospers in spite of loss of highway". The Seattle Times. p. 18.

- ^ Norton, Dee (October 11, 1964). "Highway 99 Bypass At Marysville Seen Boon By Many Businessmen". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. 5.

- ^ "Marysville 'third class' since Monday". Marysville Globe. March 29, 1962. p. 2.

- ^ Duncan, Don (April 8, 1962). "Marysville in orbit for World's Fair". The Seattle Times. p. 21.

- ^ Dougherty, Phil (July 5, 2007). "Speeding freight train rams railroad cars in front of the Marysville Great Northern Depot, demolishing the depot and killing two, on June 6, 1969". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Barr, Robert A. (June 6, 1969). "Massive rail crash kills 2". The Seattle Times. p. 1.

- ^ Aweeka, Charles (October 20, 1982). "Downtown Marysville to get $30 million facelift". The Seattle Times. p. G1.

- ^ Aweeka, Charles (November 3, 1982). "Marina owner hits development plan". The Seattle Times. p. F2.

- ^ Aweeka, Charles (December 22, 1982). "Hearing goes on and on". The Seattle Times. p. F1.

- ^ "Downtown plan receives too little support to override veto". Marysville Globe. June 29, 1983. p. 1.

- ^ a b Brunner, Jim (July 29, 1999). "Water tower will cost $113,000". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Gowenlock, Shanna (August 17, 1988). "Mall coming to life as some stores open". Marysville Globe. p. 1.

- ^ Shaw, Linda (August 2, 1989). "Marysville: Growing, growing, gone?". The Seattle Times. p. H1.

- ^ Montgomery, Nancy (October 13, 1999). "No coasting in Marysville races". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ McGaffin, Pam (March 26, 1997). "Location fuels Marysville boom". The Everett Herald. p. C1. Retrieved June 5, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Carter, Don (March 7, 1998). "Old-timers, newcomers attracted to this town". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. D1.

- ^ a b Thompson, Lynn (July 26, 2006). "Tulalip Tribes' clout on the rise". The Seattle Times. p. H14. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, Diane (September 12, 1994). "Airport-site battle heats up". The Seattle Times. p. B1.

- ^ Brooks, Diane (September 22, 1994). "Roar of 3,500 airport foes: motion to urge third runway at Sea-Tac, not new airport". The Seattle Times. p. B1.

- ^ Seinfeld, Keith (July 12, 1996). "Runway battle to land in court: regional panel OKs Sea-Tac expansion". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ Heffter, Emily (September 24, 2004). "NASCAR racetrack developer selects site near Marysville". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Heffter, Emily (November 23, 2004). "Racetrack plans fall apart: Officials wary of burden on taxpayers". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Lynn (August 17, 2005). "Push for 4-year college revs up". The Seattle Times. p. H18. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Lynn (January 18, 2008). "UW north campus: The question is where". The Seattle Times. p. B2. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "UW Snohomish County campus plans delayed again". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press. December 2, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Long, Katherine (May 24, 2011). "WSU branch campus one step closer for Everett". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Dietrich, William (April 30, 2006). "Lynnwood Redux: Where else will 100,000 newcomers a year go now?". The Seattle Times. p. 16. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Snohomish County Annexation Report, January 1, 2000 through May 31, 2006 (Report). Snohomish County. 2006. p. 38. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Boxleitner, Kirk (November 12, 2009). "Marysville City Council votes 6–1 to annex 20,000 residents". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Orsini-Meinhard, Kristen (August 1, 2007). "Retail boom puts cities in the money". The Seattle Times. p. H14.

- ^ a b Whitley, Peyton (August 17, 2005). "New park allows waterfront access from downtown". The Seattle Times. p. H4. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Sawmill demolished; M'ville could use Ebey Slough site for city hall to spark downtown renaissance". Marysville Globe. August 28, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Sheets, Bill (July 15, 2009). "Face-lift in the works for downtown Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Sheets, Bill (January 13, 2013). "Marysville seeks to revive Ebey Slough property". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Powell, Steve (February 14, 2019). "Marysville's star developer search". Marysville Globe. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Powell, Steve (July 2, 2015). "M'ville needs a catalyst for waterfront development". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Langdon, Sandy (June 24, 2016). City of Marysville, Washington Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (For the Year Ending December 31, 2015) (Report). City of Marysville. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Forecasting & Research Division (September 2016). "State of Washington 2016 Population Trends" (PDF). Washington State Office of Financial Management. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Balk, Gene (May 19, 2016). "Seattle now fourth for growth among 50 biggest U.S. cities". The Seattle Times. p. B3. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Powell, Steve (August 30, 2019). "We're growing and growing in Marysville". Marysville Globe. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Rathbun, Andy (September 13, 2010). "New Marysville Getchell High School campus opens". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "Fifth teen dies as a result of Washington state high-school shooting two weeks ago". The National Post. Associated Press. November 8, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Carter, Mike (January 10, 2016). "Father of Marysville school shooter to be sentenced". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Kaste, Martin (October 27, 2014). "Washington case revives debate about 'contagious' mass shootings". NPR. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Winters, Chris (December 22, 2016). "With new Marysville Pilchuck cafeteria, 'we're moving forward'". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ "2018 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Snohomish County Urban Growth Areas and Incorporated Cities (PDF) (Map). Snohomish County. March 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ City of Marysville (PDF) (Map). City of Marysville. January 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ a b City of Marysville Water System Plan (Report). City of Marysville. October 2016. Archived from the original on January 24, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Marysville Surface Water Comprehensive Plan Update (Report). City of Marysville. September 2016. Archived from the original on January 24, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ a b 2009 City of Marysville Stormwater Management Program (PDF) (Report). City of Marysville. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1941). "Mount Vernon to Seattle". The WPA Guide to Washington: The Evergreen State. American Guide Series. p. 436. ISBN 9781595342454. OCLC 881468746. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Alexander, Brian (July 21, 2006). "A forest playground's beauty and dangers". The Seattle Times. p. B6. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Marysville: Touches of home, history in new logo". The Seattle Times. February 2, 2005. p. H12. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ "Expert advises Marysville as students return to school". KOMO 4 News. Associated Press. November 2, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Marysville Integrated Comprehensive Plan (Report). City of Marysville. 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population: Number of Inhabitants, Washington" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. February 1982. pp. 49–12. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Balk, Gene (May 19, 2016). "U.S. Census: Seattle now fourth for growth among 50 biggest U.S. cities". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (November 5, 2012). "Marysville, WA Urbanized Area Summary File 1" (PDF). Washington State Office of Financial Management. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Marysville, Washington". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: Marysville city, Washington" (PDF). United States Census. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Selected Economic Characteristics: Marysville, Washington". American Community Survey. United States Census. September 15, 2016. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ McNichols, Joshua (January 4, 2017). "Tired of commuting, a bedroom community near Seattle takes a risk". KUOW. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Dougherty, Phil (July 5, 2007). "Fire destroys the Weiser Lumber Company in Marysville on May 6, 1955". HistoryLink. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Winters, Chris (October 26, 2015). "Marysville to buy old Welco Lumber site on Ebey Slough". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "Census snapshot: Marysville". The Everett Herald. February 9, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Snohomish County Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan Update, Volume 2: Planning Partner Annexes (Report). Snohomish County. September 2015. p. 9-1. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ "City of Marysville Draft Brownfield Cleanup Grant Application, Crown Pacific Site". City of Marysville. 2009. p. 9. Retrieved January 30, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kelly, Brian (January 28, 2002). "Quil Ceda pinching Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Dehm, M.L. (June 25, 2013). "Marysville area leads north county's growth". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Buell, Douglas (December 13, 2019). "New luxury pre-owned car dealership opens in Marysville". The Arlington Times. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Martucci, Libby (May 2, 2014). "Car dealers landing in Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Buell, Douglas (July 6, 2019). "Cascade Industrial Center: New name for investment in Arlington, Marysville". The Arlington Times. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Powell, Steve (January 6, 2017). "Manufacturing center key for M'ville in '17, mayor says". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Podsada, Janice (May 3, 2023). "Tesla leases space at Marysville business park". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Gates, Dominic (October 18, 2005). "Airbus parent to build key part of rear fuselage for Boeing 787". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Davis, Jim (August 10, 2016). "Marysville's Northside shoe company moves to bigger digs". The Herald Business Journal. The Everett Herald. p. 8. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "Washington City and Town Profiles". Municipal Research and Services Center. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b "Form of Government". City of Marysville. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ McGaffin, Pam (October 17, 1996). "Growing Marysville needs mayor full time". The Everett Herald. p. B2. Retrieved February 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelly, Brian (September 18, 2002). "Marysville leaning to keep mayor". The Everett Herald. p. B1. Retrieved February 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kelly, Brian (September 17, 2002). "Mayor, manager choice for voters". The Everett Herald. p. B1. Retrieved February 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Daybert, Amy (June 29, 2010). "Marysville City Council appoints a new mayor". The Everett Herald. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ Winters, Chris (October 12, 2015). "One contested race, fireworks ban on ballot in Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ Haglund, Noah (November 6, 2019). "Edmonds, Lake Stevens and Sultan usher in changes at the top". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Hendry, Surya (July 24, 2023). "In Lake Stevens, Marysville, voters have just 1 choice for mayor". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "City Council". City of Marysville. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ Langston, Jennifer (September 16, 2002). "Ungainly growth brings calls for city managers". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A1. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Accountability Audit Report: City of Marysville, Snohomish County (Report). Washington State Auditor. July 18, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Winters, Chris (November 13, 2014). "Marysville passes $128M budget for 2015". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Langdon, Sandy; Gritton, Denise (November 3, 2014). 2015–2016 Biennial Budget, City of Marysville, Washington (Report). City of Marysville. p. XXXI. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Baumbach, Jenelle (December 27, 2023). "3 Snohomish County cities have highest sales tax rate in state". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Davis-Leonard (May 11, 2021). "Former community hub in Marysville set for demolition". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Haun, Riley (December 17, 2022). "New civic center manifests Marysville's dream of a 'one-stop shop'". The Everett Herald. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Andersson, Christopher (October 25, 2022). "M'ville Civic Center opens to public". North County Outlook. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "Marysville Library". Sno-Isle Libraries. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Snohomish County Public Transportation Benefit Area (PDF) (Map). Community Transit. July 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Quick Facts". Snohomish County Public Utility District. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b "Puget Sound Energy service area" (PDF). Puget Sound Energy. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "About Us". Marysville Fire District. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Census Bureau Geography Division (2023). 118th Congress of the United States: Washington – Congressional District 1 (PDF) (Map). 1:118,000. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (October 24, 2022). "Incumbents DelBene, Larsen say country is heading in right direction". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Snohomish County: State Legislative Districts (Map). Snohomish County Elections. May 12, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Washington State Redistricting Commission (July 15, 2022). "Legislative District 39" (PDF) (Map). District Maps Booklet 2022. Washington State Legislative Information Center. p. 40. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Snohomish County: County Council Districts (Map). Snohomish County Elections. May 12, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Fiege, Gale (August 12, 2013). "Old lumber store gives arts group a home in Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Fiege, Gale (December 23, 2015). "Red Curtain arts group finds new home in Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Red Curtain has a new home". Red Curtain Foundation for the Arts. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Boxleitner, Kirk (October 31, 2013). "Marysville Arts Coalition debuts 'Autumn Artistry' art show Nov. 8–9". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Goffredo, Theresa (March 30, 2011). "Facebook reunites Marysville choir in song". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, Diane (September 23, 1993). "Children's place: years of dedicated effort pay off as kids' museum finds a home". The Seattle Times. p. 1.

- ^ Ochoa, Rachel (October 6, 1995). "Children's museum to reopen in Everett". The Seattle Times. p. B3. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Lloyd, Jennifer (August 1, 2004). "Museum closes, new one to open: Everett facility for kids is moving". The Seattle Times. p. B2.

- ^ Moriarty, Leslie (July 2, 2003). "Connection to the past: A Marysville museum uses donated items to dial into the history of telephones". The Seattle Times. p. H16.

- ^ Vorhees, John (June 26, 1980). "Film gives insight on Iranian revolution". The Seattle Times. p. D9.

- ^ Brunner, Jim (March 24, 1999). "Towering memories: old-timers want to save 'Space Needle of Marysville'". The Seattle Times. p. B1.

- ^ Langston, Jennifer (December 4, 2002). "True-blue fans save Marysville landmark". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Comeford Park". City of Marysville. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "M'ville's $325,000 Spray Park to open Thursday, June 26". Marysville Globe. June 18, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Jennings Memorial Park opening set soon". Marysville Globe. June 13, 1963. p. 1.

- ^ Bray, Kari (June 10, 2016). "Marysville festival celebrates strawberries and one big birthday". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Increase in polio causes closing of Marysville festival". The Seattle Times. June 8, 1949. p. 1.

- ^ Lukins, Sheila (1997). U.S.A. Cookbook. New York: Workman Publishing Company. p. 572. ISBN 978-1-56305-807-3. OCLC 36629949. Retrieved January 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Buell, Douglas (December 5, 2016). "City brings holiday cheer to community with Merrysville for the Holidays and lights parade". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Winters, Chris (April 7, 2015). "New farmers market is a long-sought 'win' for Marysville". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Andersson, Christopher (July 20, 2016). "Marysville Farmers Market open for summer". North County Outlook. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Haun, Riley (June 16, 2023). "Add these two new Snohomish County farmers markets to your weekly shopping list". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ "Newspapers & Publications". Marysville Tulalip Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Arney, Sarah; Corrigan, Tom (November 28, 2007). "Globe kicks off carrier delivery". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Marysville Globe, Arlington Times change ownership". The Arlington Times. August 10, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (April 28, 2020). "Amid falling revenue, Sound Publishing lays off 70 workers". The Everett Herald. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ "North County Outlook publishes final issue". North County Outlook. October 26, 2022. p. 1. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "City of Marysville Ordinance No. 3006". City of Marysville. November 9, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2017 – via Municipal Research and Services Center.[dead link]

- ^ Western Washington Markets (PDF) (Map). The Seattle Times Company. November 9, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Podsada, Janice (May 1, 2020). "Ziply Fiber takes over Frontier's Northwest broadband service". The Everett Herald. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ "What cable television service providers serve Marysville?". City of Marysville. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Marysville seeks 3 members for Cable TV Advisory Committee". The Seattle Times. April 14, 2004. p. H16. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Gjovaag, Helen (February 16, 1994). "City's library has come a long way". Marysville Globe. p. 1. Retrieved December 24, 2021 – via SmallTownPapers.

- ^ Barrios, Joseph (July 25, 1995). "Mukilteo casts envious eye at Marysville's new library". The Seattle Times. p. B1.

- ^ Sno-Isle Libraries 2016–2025 Capital Facilities Plan (PDF) (Report). Sno-Isle Libraries. pp. 35–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 19, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Bray, Kari (January 6, 2018). "Former vacant Smokey Point space celebrated as new library". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ^ "Our History". Marysville Historical Society. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Boxleitner, Kirk (August 29, 2012). "Marysville Historical Society breaks ground for museum". Marysville Globe. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Winter, Chris (January 26, 2016). "Marysville Historical Society's new digs to be celebrated March 19". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b "Designated historic sites in Snohomish County". The Everett Herald. July 5, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Whitely, Peyton (October 15, 2003). "Concrete link to past – Marysville's former opera house, built in 1911, has been fixed up and again hosts local events". The Seattle Times. p. H26.

- ^ McDonald, Cathy (June 7, 2001). "Jennings Park". The Seattle Times. p. G9. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Andersson, Christopher (April 9, 2019). "Marysville officials travel to China". North County Outlook. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Andersson, Christopher (April 15, 2015). "M-P grad plays professional soccer". North County Outlook. Marysville, Washington. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Brady, Robert A. (1943). Business as a System of Power. New York: Columbia University Press. p. viii. OCLC 975292258. Retrieved March 18, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Glass, Gregg (May 20, 2003). "School spotlight: Marysville-Pilchuck High School". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Lang, Andrew (October 13, 2018). "Marysville Pilchuck soccer star becomes celebrity in Fiji". The Everett Herald. Retrieved October 13, 2018.

- ^ Silver, Steve (January 21, 2009). "DeCaro moving up to AHL". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Haag, Jan. "Bytes from Haag's Bio". Jan Haag. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Well, Martin (April 29, 2015). "Charles Hamel, influential oil industry whistleblower, dies at 84". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ "Marysville native Luton selected by Jaguars in NFL draft". The Everett Herald. April 25, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ "Jack Metcalf, 1927–2007: Former congressman spent years serving state". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press. March 15, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Blecha, Peter (November 20, 2005). "Morrison, "Morrie" and Alice — Northwest Music Industry Pioneers". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Adande, J.A. (November 29, 1995). "Northwestern returns to the Rose Bowl". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Raley, Dan (July 29, 2008). "The accidental Olympian out of Marysville". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Cane, Mike (October 1, 2008). "Pahukoa brothers rank among M-P's best of all-time". The Everett Herald. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Withers, Bud (August 5, 2012). "Discus thrower Jarred Rome makes it back to Olympics after 2008 disappointment". The Seattle Times. p. C7. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Erin (March 21, 2011). "Unreleased Cobain/Love duet surfaces in new Patty Schemel documentary". Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Raley, Dan (October 21, 2003). "Where Are They Now: Steve Thompson". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Cornfield, Jerry (May 14, 2020). "As Robinson moves to the Senate, Wicks gets a House seat". The Everett Herald. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Randall, Beckye (February 12, 2009). "Sim Wilson, former newspaper publisher and legislator, dies at 81". North County Outlook. Marysville, Washington. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Marysville School District No. 25 Capital Facilities Plan, 2014–2019 (Report). Marysville School District. 2014. p. 3. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Jensen, J.J.; Sullivan, Jennifer (October 21, 2003). "Marysville teachers vote to end long strike". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Washington State K-12 School Districts (PDF) (Map). Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. February 10, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ "Grace Academy celebrates 30th anniversary". Marysville Globe. August 28, 2008. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Cosmetology school moves". The Seattle Times. March 14, 1996. p. B2. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "EvCC cosmetology program offers new three-day flex schedule, instructor training". Marysville Globe. August 23, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Washington State Highways, 2014–2015 (PDF) (Map). Washington State Department of Transportation. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ City of Marysville, Transportation Element (2008) (PDF) (Report). City of Marysville. 2008. pp. 2–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Pulkkinen, Levi (November 19, 2012). "Which Washington city's residents have the worst commutes?". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Watanabe, Ben (May 28, 2023). "$123M project starting on Highway 529 interchange, I-5 HOV lane". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Watanabe, Ben (March 2, 2023). "Work on I-5 HOV lane from Everett to Marysville starts next week". The Everett Herald. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Tax-related ballot measures passing". The Everett Herald. April 22, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Community Transit Bus Plus: Schedules & Route Maps (PDF). Community Transit. September 11, 2016. pp. 13, 105–125, 132–133, 166–169, 180–181. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Hadley, Jane (January 15, 2004). "Joint ballot planned for roads, Sound Transit". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Bergsman, Jerry (August 24, 1992). "Marysville unsure about rail: officials to talk about joining in plan tonight". The Seattle Times. p. B3.

- ^ Brooks, Diane (May 10, 1999). "Trains might go further north". The Seattle Times. p. B1. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ "State Avenue Corridor Subarea Plan". City of Marysville. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Lindblom, Mike (November 3, 2016). "Lynnwood eager for growth, changes that light rail will bring". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Winters, Chris (July 24, 2014). "Marysville faces traffic nightmare with more trains". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Fainberg, Denise (2012). "Camano Island and Arlington Area". An Explorer's Guide: Washington (2nd ed.). Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-88150-974-8. OCLC 759908478. Retrieved January 28, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "116th Interchange Project: TIGER Discretionary Grant" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. p. 13. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ McNichols, Joshua (January 12, 2017). "This is why your Marysville friends are always late for breakfast". KUOW. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Washington State Highways 2014–2015 (Map). 1:842,000. Washington State Department of Transportation. 2014. Puget Sound Area inset. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Whitely, Peyton (January 29, 2003). "Pilots' paradise: These neighbors never have the hassle of driving to the airport". The Seattle Times. p. H22. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ Snohomish County Area Bicycling & Trail Map (PDF) (Map). Community Transit. April 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Bray, Kari (February 27, 2018). "Marysville to build new trails at estuary and Whiskey Ridge". The Everett Herald. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ "Paving under way on Waterfront Trail in Marysville". Marysville Globe. September 15, 2016.

- ^ Sheets, Bill (February 19, 2008). "Marysville trail plan draws resistance". Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Draft Lakewood Neighborhood Master Plan (Report). City of Marysville. April 26, 2016. pp. 28–30. Archived from the original on January 24, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Information About Snohomish County Public Utility District No. 1" (PDF). Snohomish County Public Utility District. May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Bonneville Power Administration". Snohomish County Public Utility District. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ BPA Transmission Lines and Facilities (PDF) (Map). Bonneville Power Administration. February 2, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 28, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ WECC Path Reports: 10-Year Regional Transmission Plan (PDF) (Report). Western Electricity Coordinating Council. September 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Dudley, Brier; Miletich, Steve (August 4, 2000). "New managers at Olympic Pipe Line promise changes". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Northwest Pipeline LLC Delivery and Recipet Point System Map (PDF) (Map). Williams Companies. April 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Pipeline Maps (Map). Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Logg, Cathy (June 26, 2004). "Marysville to change refuse bins". The Everett Herald. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Recycling and Yard Waste". City of Marysville. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "City of Marysville Water Quality Report 2013". City of Marysville. 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2017.