This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

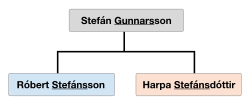

Icelandic names are names used by people from Iceland. Icelandic surnames are different from most other naming systems in the modern Western world in that they are patronymic or occasionally matronymic: they indicate the father (or mother) of the child and not the historic family lineage. Iceland shares a common cultural heritage with the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Unlike these countries, Icelanders have continued to use their traditional name system, which was formerly used in most of Northern Europe.[a] The Icelandic system is thus not based on family names (although some people do have family names and might use both systems). Generally, a person's last name indicates the first name of their father (patronymic) or in some cases mother (matronymic) in the genitive, followed by -son ("son") or -dóttir ("daughter").

Some family names exist in Iceland, most commonly adaptations from last names Icelanders adopted when living abroad, usually in Denmark. Notable Icelanders with inherited family names include former prime minister Geir Haarde, football star Eiður Smári Guðjohnsen, entrepreneur Magnús Scheving, film director Baltasar Kormákur Samper, and actress Anita Briem. Before 1925, it was legal to adopt new family names; one Icelander to do so was the Nobel Prize-winning author Halldór Laxness, while another author, Einar Hjörleifsson, and his brothers chose the family name "Kvaran". Since 1925, it has been illegal for Icelanders to adopt a family name unless they have a right to do so through inheritance.[4]

First names not previously used in Iceland must be approved by the Icelandic Naming Committee.[5] The criterion for acceptance is whether a name can easily be incorporated into the Icelandic language. With some exceptions, it must contain only letters found in the Icelandic alphabet (including þ and ð), and it must be possible to decline the name according to the language's grammatical case system, which in practice means that a genitive form can be constructed in accordance with Icelandic rules. Names considered to be gender-nonconforming were historically not allowed, but in 2013, a 15-year-old girl named Blær (a masculine noun in Icelandic) was allowed to keep her name in a court decision that overruled an initial rejection by the naming committee.[6] Her mother, Björk Eiðsdóttir, did not realize at the time that "Blær" was considered masculine; she had read Halldór Laxness's novel The Fish Can Sing, which has a female character named Blær, meaning "light breeze", and decided that if she had a daughter, she would name her Blær.[7]

In 2019, the laws governing names were changed. First names are no longer restricted by gender. Moreover, Icelanders who are officially registered as nonbinary are permitted to use the patro/matronymic suffix -bur ("child of") instead of -son or -dóttir.[8]

Typical Icelandic naming

editA man named Jón Einarsson has a son named Ólafur. Ólafur's last name will not be Einarsson like his father's; it will be Jónsson, indicating that Ólafur is the son of Jón (Jóns + son). The same practice is used for daughters. Jón Einarsson's daughter Sigríður's last name is not Einarsson but Jónsdóttir. Again, the name means "Jón's daughter" (Jóns + dóttir).

In some cases, a person's surname is derived from their parent's second given name instead of the first. For example, if Jón is the son of Hjálmar Arnar Vilhjálmsson, he may either be named Jón Hjálmarsson (Jón, son of Hjálmar) or Jón Arnarsson (Jón, son of Arnar). The reason for this may be that the parent prefers to be called by the second given name instead of the first; this is fairly common. It may also be that the parent's second name seems to fit the child's first name better.

In cases where two people in the same social circle bear the same first name and the same father's name, they have traditionally been distinguished by their paternal grandfather's name (avonymic), e.g. Jón Þórsson Bjarnasonar (Jón, son of Þór, son of Bjarni) and Jón Þórsson Hallssonar (Jón, son of Þór, son of Hallur). This practice has become less common (the use of middle names having replaced it), but features conspicuously in the Icelandic sagas.

Matronymic naming as a choice

editThe vast majority of Icelandic last names carry the name of the father, but occasionally the mother's name is used: e.g. if the child or mother wishes to end social ties with the father. Some women use it as a social statement while others simply choose it as a matter of style.

In all of these cases, the convention is the same: Ólafur, the son of Bryndís, will have the full name Ólafur Bryndísarson ("son of Bryndís"). Some well-known Icelanders with matronymic names are the football player Heiðar Helguson ("Helga's son"), the novelist Guðrún Eva Mínervudóttir ("Minerva's daughter"), and the medieval poet Eilífr Goðrúnarson ("Goðrún's son").

In the Icelandic film Bjarnfreðarson the title character's name is the subject of some mockery for his having a matronymic – as Bjarnfreður's son – rather than a patronymic. In the film this is connected to the mother's radical feminism and shame over his paternity, which are part of the film's plot.[9] Some people have both a matronymic and a patronymic, such as Dagur Bergþóruson Eggertsson ("the son of Bergþóra and Eggert"), the mayor of Reykjavík since 2014. Another example is the girl Blær mentioned above: her full name is Blær Bjarkardóttir Rúnarsdóttir ("the daughter of Björk and Rúnar").

Icelandic singer-songwriter Björk had a daughter in 2002 with American contemporary artist and filmmaker Matthew Barney. The pair named her Ísadóra Bjarkardóttir Barney, giving her two last names of different origin: Barney, her father's last name (following the Western tradition of giving a child their father's last name, usually a collective family name), and Bjarkardóttir, a conventional Icelandic matronymic.

Gender-neutral patronymics and matronymics

editA gender autonomy act the Icelandic Parliament approved in 2019 allows people who register their gender as neutral (i.e., non-binary) to use bur, a poetic word for "son", to be repurposed as a neuter suffix instead of son or dóttir.[10][11][12]

History

editUnlike the other Nordic countries, Iceland never formalized a system of family names.[13] A growing number of Icelanders—primarily those who had studied abroad—began to adopt family names in the second half of the 19th century. In 1855, there were 108 family names. In 1910 there were 297.[13] In 1913, the Althing legalized the adoption of family names. Icelanders who had family names tended to be upper-class and serve as government officials.[13]

In 1925, Althing banned the adoption of new family names.[13] Some common arguments against using family names were that they were not authentically "Icelandic"; that the usage of -son in family names made it unclear whether the name was a family name or patronymic; and that low-class people could adopt the family names of well-known upper-class families.[13] Some common arguments for using family names were that they made it easier to trace lineages and to distinguish individuals (a problem in mid-19th century Iceland was that there were so many people named Jón—in fact, one in six Icelandic males were named Jón at the time) and that Iceland ought to follow the lead of its Nordic neighbours.[13]

In Russia, where name-patronyms of similar style were historically used (such as Ivan Petrovich which means Ivan, the son of Peter), the much larger population necessitated family names, relegating the patronymic to a middle name and conversational honorific.

Cultural ramifications

editIn Iceland, listings such as the telephone directory are alphabetised by first name rather than surname. To reduce ambiguity, the directory also lists professions.

Icelanders formally address others by their first names. By way of example, the former prime minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir would not be introduced as 'Ms Sigurðardóttir' but by either her first name or her full name, and usually addressed by her first name only. Icelandic singer Björk goes by her first name (her full name is Björk Guðmundsdóttir). Björk is how any Icelander would address her, whether formally or casually.

In the case of two people in the same group having the same given name, perhaps one named Jón Stefánsson and the other Jón Þorláksson, one could address Jón Stefánsson as "Jón Stefáns" and Jón Þorláksson as "Jón Þorláks". When someone has a conversation with two such people at the same time, "son" need not be used; in that case, the genitive form of the father's name could be used like a nickname, although it is just as common in such cases to refer to people by their middle names (having a middle name being nowadays the general rule for people with a common name like 'Jón').

Because the vast majority of Icelanders use patronymics, a family will normally have a variety of last names: the children of (married or unmarried) parents Jón Einarsson and Bryndís Atladóttir could be named Ólafur Jónsson and Katrín Jónsdóttir. With matronymics, the children in this example would be Ólafur Bryndísarson and Katrín Bryndísardóttir. Patronymics thus have the formula (genitive case of father's name, usually adding -s, or if the name ends in -i, it will change to -a) + son/dóttir/bur, while matronymics are (genitive case of mother's name, often -ar, or if the name ends in -a, it will change to -u) + son/dóttir/bur.

Outside of Iceland

editThe Icelandic naming system occasionally causes problems for families travelling abroad, especially with young children, since non-Icelandic immigration staff (apart from those of other Nordic countries) are usually unfamiliar with the practice and therefore expect children to have the same last names as that of their parents.[citation needed]

Icelandic footballers who work abroad similarly are called by their patronymics, even though that is improper from an Icelandic standpoint. Aron Gunnarsson, for example, wore the name "Gunnarsson" on the back of his shirt in the Premier League before his move to Al-Arabi, and was referred to as such by the British media and commentators.[citation needed]

The TV personality Magnus Magnusson acquired his repetitive name when his parents adopted British naming conventions (and Magnus's father's patronymic) during World War II, Magnus having been named at birth Magnús Sigursteinsson.[citation needed]

Expatriate Icelanders or people of Icelandic descent who live in foreign countries, such as the significant Icelandic community in Manitoba, Canada, usually abandon the traditional Icelandic naming system. In most cases, they adopt the naming convention of their country of residence—most commonly by retaining the patronymic of their first ancestor to immigrate to the new country as a permanent family surname, much as other Nordic immigrants did before surnames became fully established in their own countries.[14] Alternatively, a permanent family surname may sometimes be chosen to represent the family's geographic rather than patronymic roots; for example, Canadian musician Lindy Vopnfjörð's grandfather immigrated to Canada from the Icelandic village of Vopnafjörður.[15]

See also

edit- Germanic name

- Icelandic grammar for details on how genitive works in Icelandic

- Icelandic language

- List of Icelanders

- Scandinavian family name etymology

- Naming conventions similar to Icelandic names:

- Generally:

- Some specific cultural examples:

Notes

edit- ^ The system has recently been reintroduced as an option elsewhere in the Nordic countries. Current law in Denmark (since 2005),[1] the Faroe Islands (since 1992), Norway (since 2002), and Sweden[2] (since 1982) allows the use of patronymics as a replacement for (or addition to) traditional surnames. In Finland it is possible to give a child a patronym or matronym, but they are registered as given names.[3]

References

edit- ^ "Fornavne, mellemnavne og efternavne". Ankestyrelsen. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Surnames with the suffix -son or -dotter". Swedish Patent and Registration Office. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Nimilaki Archived 10 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine (694/1985) § 26. Retrieved 3-11-2008. (in Finnish)

- ^ "Personal Names Act, No. 45 of 17th May 1996". Ministry of the Justice. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ "Naming Committee accepts Asía, rejects Magnus". Morgunblaðið online. 12 September 2006. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012 – via Iceland Review Online.

- ^ Blaer Bjarkardottir, Icelandic Teen, Wins Right To Use Her Given Name Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Huffington Post, 31 January 2013

- ^ "Where Everybody Knows Your Name, Because It's Illegal". The Stateless Man. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013.

- ^ Kyzer, Larissa (22 June 2019). "Icelandic names will no longer be gendered". Iceland Review. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ TheLurkingFox (26 December 2009). "Mr. Bjarnfreðarson (2009)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "9/149 frumvarp: mannanöfn | Þingtíðindi | Alþingi". althingi.is. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Lög um kynrænt sjálfræði. | Þingtíðindi | Alþingi". althingi.is. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Stúlkur mega nú heita Ari og drengir Anna | RÚV". ruv.is. 21 June 2019. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Björnsson, Páll (Fall 2017). "Ættarnöfn - eður ei". Saga.

- ^ "Icelandic anchor makes Manitoba connection". Winnipeg Free Press, 26 July 2008.

- ^ "Where Are They Now?" Lögberg-Heimskringla, 24 February 1995.

External links

edit- Information on Icelandic Surnames (Ministry of the Interior)

- English translation of the Personal Names Act No. 45 of 17 May 1996 (Ministry of the Interior)