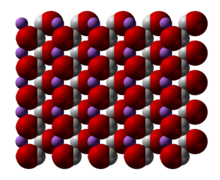

Lithium hydroxide is an inorganic compound with the formula LiOH. It can exist as anhydrous or hydrated, and both forms are white hygroscopic solids. They are soluble in water and slightly soluble in ethanol. Both are available commercially. While classified as a strong base, lithium hydroxide is the weakest known alkali metal hydroxide.

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lithium hydroxide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.804 |

| 68415 | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 2680 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| LiOH | |

| Molar mass |

|

| Appearance | white solid |

| Odor | none |

| Density |

|

| Melting point | 462 °C (864 °F; 735 K) |

| Boiling point | 924 °C (1,695 °F; 1,197 K) (decomposes) |

| |

| Solubility in methanol |

|

| Solubility in ethanol |

|

| Solubility in isopropanol |

|

| Acidity (pKa) | 14.4[3] |

| Conjugate base | Lithium monoxide anion |

| −12.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

|

| 4.754 D[4] | |

| Thermochemistry[5] | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

49.6 J/(mol·K) |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

42.8 J/(mol·K) |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−487.5 kJ/mol |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−441.5 kJ/mol |

Enthalpy of fusion (ΔfH⦵fus)

|

20.9 kJ/mol (at melting point) |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Corrosive |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

210 mg/kg (oral, rat)[6] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | "ICSC 0913". "ICSC 0914". (monohydrate) |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Lithium amide |

Other cations

|

|

Related compounds

|

Lithium oxide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Production

editThe preferred feedstock is hard-rock spodumene, where the lithium content is expressed as % lithium oxide.

Lithium carbonate route

editLithium hydroxide is often produced industrially from lithium carbonate in a metathesis reaction with calcium hydroxide:[7]

- Li2CO3 + Ca(OH)2 → 2 LiOH + CaCO3

The initially produced hydrate is dehydrated by heating under vacuum up to 180 °C.

Lithium sulfate route

editAn alternative route involves the intermediacy of lithium sulfate:[8][9]

- α-spodumene → β-spodumene

- β-spodumene + CaO → Li2O + ...

- Li2O + H2SO4 → Li2SO4 + H2O

- Li2SO4 + 2 NaOH → Na2SO4 + 2 LiOH

The main by-products are gypsum and sodium sulphate, which have some market value.

Commercial setting

editAccording to Bloomberg, Ganfeng Lithium Co. Ltd.[10] (GFL or Ganfeng)[11] and Albemarle were the largest producers in 2020 with around 25kt/y, followed by Livent Corporation (FMC) and SQM.[10] Significant new capacity is planned, to keep pace with demand driven by vehicle electrification. Ganfeng are to expand lithium chemical capacity to 85,000 tons, adding the capacity leased from Jiangte, Ganfeng will become the largest lithium hydroxide producer globally in 2021.[10]

Albemarle's Kemerton WA plant, originally planned to deliver 100kt/y has been scaled back to 50kt/y.[12]

In 2020 Tianqi Lithium's, plant in Kwinana, Western Australia is the largest producer, with a capacity of 48kt/y.[13]

Applications

editLithium-ion batteries

editLithium hydroxide is mainly consumed in the production of cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries such as lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2) and lithium iron phosphate. It is preferred over lithium carbonate as a precursor for lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxides.[14]

Grease

editA popular lithium grease thickener is lithium 12-hydroxystearate, which produces a general-purpose lubricating grease due to its high resistance to water and usefulness at a range of temperatures.

Carbon dioxide scrubbing

editLithium hydroxide is used in breathing gas purification systems for spacecraft, submarines, and rebreathers to remove carbon dioxide from exhaled gas by producing lithium carbonate and water:[15]

- 2 LiOH·H2O + CO2 → Li2CO3 + 3 H2O

or

- 2 LiOH + CO2 → Li2CO3 + H2O

The latter, anhydrous hydroxide, is preferred for its lower mass and lesser water production for respirator systems in spacecraft. One gram of anhydrous lithium hydroxide can remove 450 cm3 of carbon dioxide gas. The monohydrate loses its water at 100–110 °C.

Precursor

editLithium hydroxide, together with lithium carbonate, is a key intermediates used for the production of other lithium compounds, illustrated by its use in the production of lithium fluoride:[7]

- LiOH + HF → LiF + H2O

Other uses

editIt is also used in ceramics and some Portland cement formulations, where it is also used to suppress ASR (concrete cancer).[16]

Lithium hydroxide (isotopically enriched in lithium-7) is used to alkalize the reactor coolant in pressurized water reactors for corrosion control.[17] It is good radiation protection against free neutrons.

Price

editIn 2012, the price of lithium hydroxide was about US$5–6/kg.[18]

In December 2020, it had risen to $9/kg[19]

On 18 March 2021, the price had risen to $11.50/kg[20]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ a b c Khosravi J (2007). Production of Lithium Peroxide and Lithium Oxide in an Alcohol Medium. Chapter 9: Results. ISBN 978-0-494-38597-5.

- ^ Popov K, Lajunen LH, Popov A, Rönkkömäki H, Hannu-Kuure H, Vendilo A (2002). "7Li, 23Na, 39K and 133Cs NMR comparative equilibrium study of alkali metal cation hydroxide complexes in aqueous solutions. First numerical value for CsOH formation". Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 5 (3): 223–225. doi:10.1016/S1387-7003(02)00335-0. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ CRC handbook of chemistry and physics : a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. William M. Haynes, David R. Lide, Thomas J. Bruno (2016-2017, 97th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida. 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5428-6. OCLC 930681942.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ CRC handbook of chemistry and physics : a ready-reference book of chemical and physical data. William M. Haynes, David R. Lide, Thomas J. Bruno (2016-2017, 97th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida. 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5428-6. OCLC 930681942.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Chambers M. "ChemIDplus – 1310-65-2 – WMFOQBRAJBCJND-UHFFFAOYSA-M – Lithium hydroxide anhydrous – Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information". chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ a b Wietelmann U, Bauer RJ (2000). "Lithium and Lithium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_393. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ "Proposed Albemarle Plant Site" (PDF). Albemarle. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Corporate presentation" (PDF). Nemaska Lithium. May 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "China's Ganfeng to Be Largest Lithium Hydroxide Producer". BloombergNEF. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Ganfeng Lithium Group". Ganfeng Lithium. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Stephens, Kate; Lynch, Jacqueline (27 August 2020). "Slowing demand for lithium sees WA's largest refinery scaled back". www.abc.net.au.

- ^ "Largest of its kind lithium hydroxide plant launched in Kwinana". Government of Western Australia. 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Barrera, Priscilla (27 June 2019). "Will Lithium Hydroxide Really Overtake Lithium Carbonate? | INN". Investing News Network. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Jaunsen JR (1989). "The Behavior and Capabilities of Lithium Hydroxide Carbon Dioxide Scrubbers in a Deep Sea Environment". US Naval Academy Technical Report. USNA-TSPR-157. Archived from the original on 2009-08-24. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Kawamura M, Fuwa H (2003). "Effects of lithium salts on ASR gel composition and expansion of mortars". Cement and Concrete Research. 33 (6): 913–919. doi:10.1016/S0008-8846(02)01092-X. OSTI 20658311. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ Managing Critical Isotopes: Stewardship of Lithium-7 Is Needed to Ensure a Stable Supply, GAO-13-716 // U.S. Government Accountability Office, 19 September 2013; pdf

- ^ "Lithium Prices 2012". investingnews.com. Investing News Network. 14 June 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "London Metal Exchange: Lithium prices". London metal exchange. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "LITHIUM AT THE LME". LME The London Metal Exchange. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

External links

edit- International Chemical Safety Card 0913 (anhydrous)

- International Chemical Safety Card 0914 (monohydrate)