Ramon Llull TOSF (Catalan: [rəˈmoɲ ˈʎuʎ]; c. 1232[a] – possibly 25 March[4] 1315/1316), [b] was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, Christian apologist and former knight from the Kingdom of Majorca.

Ramon Llull | |

|---|---|

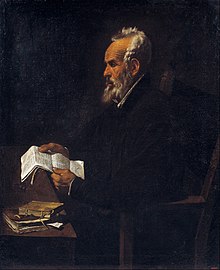

Anachronistic portrait of Ramon Llull by Francisco Ribalta (1620) | |

| Born | c. 1232 City of Mallorca, Kingdom of Majorca (now Palma, Spain) |

| Died | possibly 25 March 1315 or 1316 (aged 83–84) |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 11 September 1847 by Pope Pius IX |

| Feast | 30 June (Third Order of St. Francis) |

Philosophy career | |

Anachronistic image of Ramon Llull with speech scroll, by an unknown artist (16th–17th century) | |

| Notable work | |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Lullism |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

He invented a philosophical system known as the Art, conceived as a type of universal logic to prove the truth of Christian doctrine to interlocutors of all faiths and nationalities. The Art consists of a set of general principles and combinatorial operations. It is illustrated with diagrams.

A prolific writer, he is also known for his literary works written in Catalan, which he composed to make his Art accessible to a wider audience. In addition to Catalan and Latin, he also probably wrote in Arabic (although no texts in Arabic survive). His books were translated into Occitan, French, and Castilian during his lifetime.[5]

Although his work did not enjoy huge success during his lifetime, he has had a rich and continuing reception. In the early modern period his name became associated with alchemical works.[6] More recently he has been recognized as a precursor of the modern field of social choice theory, 450 years before Borda and Condorcet's investigations reopened the field.[7][8] His ideas also prefigured the development of computation theory.[2][9][10]

Life

editEarly life and family

editLlull was born in Palma into a wealthy family of Barcelona patricians who had come to the Kingdom of Majorca in 1229 with the conquering armies of James I of Aragon. James I had conquered the formerly Almohad-ruled Majorca as part of a larger move to integrate the territories of the Balearic Islands (now part of Spain) into the Crown of Aragon. Llull was born there a few years later, in 1232 or 1233. Muslims still constituted a large part of the population of Majorca and Jews were present in cultural and economic affairs.[11]

In 1257 Llull married Blanca Picany, with whom he had two children, Domènec and Magdalena.[12][13][14][15][16][17] Although he formed a family, he lived what he would later call the licentious and worldly life of a troubadour.

Religious calling

editIn 1263 Llull experienced a series of visions. He narrates the event in his autobiography Vita coaetanea ("A Contemporary Life"):

Ramon, while still a young man and Seneschal to the King of Majorca, was very given to composing worthless songs and poems and to doing other licentious things. One night he was sitting beside his bed, about to compose and write in his vulgar tongue a song to a lady whom he loved with a foolish love; and as he began to write this song, he looked to his right and saw our Lord Jesus Christ on the Cross, as if suspended in mid-air.[18]

The vision came to Llull five times in all and inspired in him three intentions: to give up his soul for the sake of God's love and honor, to convert the Saracens (i.e., Arabs and/or Muslims) to Christianity, and write the best book in the world against the errors of the unbelievers.[19]

Following his visions he sold his possessions on the model of Saint Francis of Assisi and set out on pilgrimages to the shrines of Saint Mary of Rocamadour, Saint James, and other places, never to come back to his family and profession. When he returned to Majorca he purchased a Muslim slave in order to learn Arabic from him.[20] For the next nine years, until 1274, he engaged in study and contemplation in relative solitude. He read extensively in both Latin and Arabic, learning both Christian and Muslim theological and philosophical thought.[21]

In 1270 Llull founded the hermitage of the Holy Trinity in Mallorca, known as Miramar. [22]

Between 1271 and 1274 Llull wrote his first works, a compendium of the Muslim thinker Al-Ghazali's logic and the Llibre de contemplació en Déu (Book on the Contemplation of God), a lengthy guide to finding truth through contemplation.

In 1274, while staying at a hermitage on Puig de Randa, the form of the great book Llull was to write was finally given to him through divine revelation: a complex system that he named his Art, which would become the motivation behind most of his life's efforts.

Missionary work and education

editLlull urged the study of Arabic and other languages in Europe,[23] in order to convert Muslims and schismatic Christians.[24] He travelled through Europe to meet popes, kings, and princes, trying to establish special colleges to prepare future missionaries.[25] In 1276 a language school for Franciscan missionaries was founded at Miramar, funded by the King of Majorca.[26]

About 1291 he went to Tunis, preached to the Saracens, disputed with them in philosophy, and after another brief sojourn in Paris, returned to the East as a missionary.[27] Llull travelled to Tunis a second time in about 1304, and wrote numerous letters to the king of Tunis, but little else is known about this part of his life.[28][29]

He returned in 1308, reporting that the conversion of Muslims should be achieved through prayer, not through military force. He finally achieved his goal of linguistic education at major universities in 1311 when the Council of Vienne ordered the creation of chairs of Hebrew, Arabic and Chaldean (Aramaic) at the universities of Bologna, Oxford, Paris, and Salamanca as well as at the Papal Court.[28]

Llull called for the expulsion of Jews who were unwilling to convert to Christianity, and influenced later European monarchs to expel Jews in practice.[30]

Death

editIn 1314, at the age of 82, Llull traveled again to Tunis, possibly prompted by the correspondence between King James II of Aragon and al-Lihyani, the Hafsid caliph, indicating that the caliph wished to convert to Christianity. Whereas Llull had been met with difficulties during his previous visits to North Africa, he was allowed to operate this time without interference from the authorities due to the improved relations between Tunis and Aragon.[31]

His last work is dated December 1315 in Tunis. The circumstances of his death remain unknown. He probably died sometime between then and March 1316, either in Tunis, on the ship on the return voyage, or in Majorca upon his return.[32] Llull's tomb, created in 1448, is in the Franciscan church in Palma, Majorca.[33]

He was beatified on 11 September 1847 by Pope Pius IX.

Works

editLlull's Art

editLlull's Art (in Latin Ars) is at the center of his thought and undergirds his entire corpus. It is a system of universal logic based on a set of general principles activated in a combinatorial process. It can be used to prove statements about God and Creation (e.g., God is a Trinity). Often the Art formulates these statements as questions and answers (e.g., Q: Is there a Trinity in God? A: Yes.). It works cumulatively through an iterative process; statements about God's nature must be proved for each of His essential attributes in order to prove the statement true for God (i.e., Goodness is threefold, Greatness is threefold, Eternity is threefold, Power is threefold, etc.).

What sets Llull's system apart is its unusual use of letters and diagrams, giving it an algebraic or algorithmic character. He developed the Art over the course of many decades, writing new books to explain each new version. The Art's trajectory can be divided into two main phases, although each phase contains numerous variations. The first is sometimes called the Quaternary Phase (1274 - 1290) and the second the Ternary Phase (1290 - 1308). This terminology was coined by Anthony Bonner.[34]

Quaternary Phase

editThe two main works of the Quaternary Phase are the Ars compendiosa inveniendi veritatem (ca. 1274) and the Ars demonstrativa (ca. 1283).[35] The Ars demonstrativa has twelve main figures. A set of sixteen principles, or 'dignities' (divine attributes) comprise the general foundation for the system's operation. These are contained in the first figure (Figure A) and assigned letters (B through R). The rest of the figures enable the user to take these principles and elaborate to demonstrate the truth of statements. Figure T is important because it contains "relational principles"(i.e. minority, majority, equality), also assigned letters. The Art then lists combinations of letters as a sort of visual aid for the process of working through every possible combination of principles. Figure S displays the Augustinian powers of the soul (will, intellect, and memory) and their acts (willing, understanding, remembering). Figure S was eliminated from the Art after 1290. Even in subsequent versions of the Art Llull maintained that the powers of the soul needed to be in alignment for a proper operation of the Art. This differentiates Llull's system from Aristotelian logic. Because classical logic did not take the powers of the soul into account it was ill-equipped to handle theological issues, in Llull's view.

Ternary Phase

editLlull inaugurated the Ternary Phase with two works written in 1290: the Ars inventiva veritatis and the Art amativa.[34] The culmination of this phase came in 1308 with a finalized version of the Art called the Ars generalis ultima. In the same year Llull wrote an abbreviated version called the Ars brevis. In these works Llull revised the Art to have only four main figures. He reduced the number of divine principles in the first figure to nine (goodness, greatness, eternity, power, wisdom, will, virtue, truth, glory). Figure T also now has nine relational principles (difference, concordance, contrariety, beginning, middle, end, majority, equality, minority), reduced from fifteen. Llull kept the combinatorial aspect of the process.

Correlatives

editLlull introduced an aspect of the system called the "correlatives" just before the final transition to the Ternary Phase. The correlatives first appear in a work called the Lectura super figuras Artis demonstrativae (c.1285-7) and came to undergird his formulation of the nature of being.[36] The doctrine of correlatives stipulates that everything, at the level of being, has a threefold structure: agent, patient, act. For example, the divine principle "goodness" consists of "that which does good" (agent), "that which receives good" (patient), and "to do good" (act). Llull developed a system of Latin suffixes to express the correlatives, i.e. bonitas (goodness); bonificans, bonificatus, bonificare. This became the basis for proving that the divine principles are distinct yet equivalent in God (each principle has the same underlying threefold structure, yet retains its own unique correlatives). This supports the combinatorial operation of the Art (i.e., this means that in God goodness is greatness and greatness is goodness, goodness is eternity and eternity is goodness, etc.), the Lullian proof of the Trinity (each divine principle has the three correlatives and together the principles comprise the Godhead, therefore the Godhead is threefold) and the Incarnation (the active and passive correlatives are equivalent to matter and form, and the trinitarian unfolding of being occurs on all levels of reality).[37]

Other works

editInfluence of Islam and early works

editIt has been pointed out that the Art's combinatorial mechanics bear a resemblance to zairja, a device used by medieval Arab astrologers.[38][39] The Art's reliance on divine attributes also has a certain similarity to the contemplation of the ninety-nine Names of God in the Muslim tradition.[40] Llull's familiarity with the Islamic intellectual tradition is evidenced by the fact that his first work (1271-2) was a compendium of Al-Ghazali's logic.[41]

Dialogues

editFrom early in his career Llull composed dialogues to enact the procedure of the Art.[42] This is linked to the missionary aspect of the Art. Llull conceived it as an instrument to convert all peoples of the world to Christianity and experimented with more popular genres to make it easier to understand. His earliest and most well known dialogue is the Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men, written in Catalan in the 1270s and later translated into Latin. It is framed as a meeting of three wise men (a Muslim, a Jew, and a Christian) and a Gentile in the woods. They learn about the Lullian method when they encounter a set of trees with leaves inscribed with Lullian principles. Lady Intelligence appears and informs them of the properties of the trees and the rules for implementing the leaves. The wise men use the trees to prove their respective Articles of Faith to the Gentile (although some of the Islamic tenets cannot be proved with the Lullian procedure) and in the end the Gentile is converted to Christianity. Llull also composed many other dialogues. Later in his career when he became concerned with heretical activity in the Arts Faculty of the University of Paris, he wrote "disputations" with philosophers as interlocutors.[43][44] He also created a character for himself and he stars in many of these dialogues as the Christian wise man (for instance: Liber de quaestione valde alta et profunda, composed in 1311).

Tree diagrams

editLlull structured many of his works around trees. In some, like the Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men, the "leaves" of the trees stand for the combinatorial elements (principles) of the Art. In other works a series of trees shows how the Art generates all ("encyclopedic") knowledge. The Tree of Science (1295-6) comprises sixteen trees ranging from earthly and moral to divine and pedagogical.[45] Each tree is divided into seven parts (roots, trunk, branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, fruits). The roots always consist of the Lullian divine principles and from there the tree grows into the differentiated aspects of its respective category of reality.[46]

Novels

editLlull also wrote narrative prose drawing on the literary traditions of his time (epic, romance) to express the Art. These works were intended to communicate the potentially complex operations of the Art to a lay audience. Blanquerna (c.1276-83) is his most well known novel. Felix (1287-9) is also notable, although it was not widely circulated during his lifetime and was only available in Catalan. It is formulated as a sort of Bildungsroman in which Felix, the main character, sets out on a journey at the instigation of his father who has written the "Book of Wonders". The book is divided into ten chapters (echoing the encyclopedic range of the Tree of Science) as Felix gains knowledge: God, angels, heavens, elements, plants, minerals, animals, man, Paradise, and Hell. It turns out to be a metafiction, as Felix's journey ends at a monastery where he relates the "Book of Wonders" now embellished and fused with the account of his own adventures.[47]

Reception

editMedieval

editAcademic theology

editAccording to Llull's autobiographical Vita, his Art was not received well at the University of Paris when he first presented it there in the 1280s. This experience supposedly is what led him to revise the Art (creating the tertiary version). Llull's Art was never adopted by mainstream academia of the thirteenth and early-fourteenth centuries, but it did accrue quite a bit of interest. A significant number of Lullian manuscripts were collected by the Carthusian monks of Paris at Vauvert and by several theologians who donated their manuscripts to the Sorbonne Library. One disciple, Thomas Le Myésier, went so far as to create elaborate compilations of Llull's works, including a manuscript dedicated to the queen of France.[48]

Opposition

editIn the 1360s the inquisitor Nicholas Eymerich condemned Lullism in Aragon. He obtained a papal bull in 1376 to prohibit Lullian teaching, although it proved ineffective. In Paris Jean Gerson also issued a series of polemical writings against Lullism. There was an official document issued to prohibit the Lullian Art from being taught in the Faculty of Theology.[49]

Early modern

editAcademic theology

editLlull's most significant early modern proponent was Nicholas of Cusa. He collected many works by Llull and adapted many aspects of Lullian thought for his own mystical theology.[50] There was also growing interest in Lullism in Catalonia, Italy, and France. Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples published eight of Llull's books in 1499, 1505, and 1516. Lefèvre was therefore responsible for the first significant circulation of Llull's work in print outside of Catalonia.[51] It is thought that the influence of Lullian works in Renaissance Italy (coinciding with the rise of neoplatonism) contributed to a development in metaphysics, from a static Artistotelian notion of being to reality as a dynamic process.[52] In Northern and Central Europe Lullism was adopted by Lutherans and Calvinists interested in promoting programs of theological humanism. Gottfried Leibniz was exposed to these currents during his years in Mainz, and Llull's Art clearly informed his De Arte Combinatoria.[53]

Pseudo-Llull and alchemy

editThere is a significant body of alchemical treatises falsely attributed to Llull. The two fundamental works of the corpus are the Testamentum and the Liber de secretis naturae seu de quinta essentia which both date to the fourteenth century.[54] Occultists such as Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and Giordano Bruno were inspired by these works.[55] Despite Llull's growing identification with alchemy and Neoplatonic mysticism, others (such as Giulio Pace and Johann Heinrich Alsted) were still interested in the Lullian Art as a universal logic, even in the seventeenth century when Descartes and Ramus proposed competing systems.[56]

Numerous alchemical works have been attributed to Llull, but all of them are apocryphal.[57] Since the 19th century, historical criticism has been well established as to the pseudepigraphic nature of the entire corpus, which in total exceeds one hundred works.[58] Until the 1980s, historians of science thought that the oldest and most important texts were forgeries from the late 14th and early 15th centuries, with later additions. At the end of the 20th century, Professor Michela Pereira revealed an earlier textual matrix, dated around 1332, which has no pseudepigraphic intent in its genesis.[59] It is an original production by an unknown personage, whom Pereira calls magister Testamenti in reference to his most emblematic treatise. His original works would tentatively be the Testamentum, Vademecum (Codicillus); Liber lapidarii (=Lapidarius abbreviatus); Liber de intentione alchimistarum; Scientia de sensibilibus (=Ars intelectiva; Ars mágica); Tratatu de aquis medicinalius (=De secretis naturae early versions); De lapide maiori (=Apertorium); Questionario; Liber experimentorum and an early version of the Compendium animae transmutationis metallorum (=Compendium super lapidum; Lapidarium). To this primordial nucleus other writings would have been added in the course of time.

His contribution completely changed the way of analysing this germinal group of treatises, since for the first time it was revealed to us with concrete data that we were not dealing with conscious forgeries, but with original works, which transmit the ideas, the personality and the biographical data of a real alchemist. After compiling information about this personage based on what he explains, both in his Testamentum and in the other writings he cites as his own, he has been identified with a man called Raymundus de Terminis (cat. Ramon de Tèrmens).[60] He would have been a Mallorcan who exercised the office of eques or miles, trained as a magister in artibus or in legibus. These types of people usually occupied administrative, mercantile jurisdiction, diplomatic or public order posts. He also had a knowledge of medicine, especially related to surgery, having trained in Montpellier. His activity is documented on the island of Corfu and in Albanian towns. He was a capitaneo or comitis in Berat and Vlorë, and he did representative work for Robert I of Naples and Philip I of Taranto in commercial operation throughout the Adriatic and Ionian Seas.

Among his best known works is the Liber de secretis natura sive de quinta essentia. Ramon de Térmens himself was the author of several early versions or strata of this work from 1330-1332. However, the best known format, since it was the only one printed until now, is a pseudepigraphic recension dated around 1360-1380 and produced in a Catalan milieu, where some forgers endorsed the work to Ramon Llull.[61]

Iberian Revival and beatification

editMeanwhile, in Spain, the Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, Archbishop of Toledo, had taken up Lullism for his project of reform. Cisneros mobilized various intellectuals and editors, founding chairs at universities and publishing Llull's works.[62] Founded in 1633, the Pontifical College of La Sapiencia on Majorca became the epicenter for teaching Lullism. The Franciscans from La Sapiencia were the ones to seek Llull's canonization at Rome in the seventeenth century. These efforts were renewed in the eighteenth century, but never succeeded.[63] Llull was beatified in 1847 by Pope Pius IX. His feast day was assigned to 30 June and is celebrated by the Third Order of St. Francis.[64]

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries

editScholarship

editLlull is now recognized by scholars as significant in both the history of Catalan literature as well as intellectual history. From 1906 to 1950 the Comissió Editora Lul·liana led a project to edit Llull's works written in Catalan. This series was called the Obres de Ramon Llull (ORL). In 1957 the Raimundus-Lullus-Institut was founded in Freiburg, Germany to begin the work of editing Llull's Latin works. This series is called the Raimundi Lulli Opera Latina (ROL) and is still ongoing.[65] In 1990 the work on the Catalan texts was restarted with the Nova Edició de les Obres de Ramon Llull (NEORL).[66] In the world of English-language scholarship the work of Frances Yates on memory systems (The Art of Memory, published 1966) brought new interest to Ramon Llull as a figure in the history of cognitive systems.

Art and fiction

editLlull has appeared in the art and literature of the last century, especially in the genres of surrealism, philosophical fantasy, and metafiction. Salvador Dalí's alchemical thought was influenced by Ramon Llull and Dalí incorporated the diagrams from the Lullian Art into his work called Alchimie des Philosophes.[67] In 1937 Jorge Luis Borges wrote a snippet called "Ramon Llull's Thinking Machine" proposing the Lullian Art as a device to produce poetry.[68] Other notable references to Ramon Llull are: Aldous Huxley's short story The Death of Lully, a fictionalized account aftermath of Llull's stoning in Tunis, set aboard the Genoese ship that returned him to Mallorca.[69] Paul Auster refers to Llull (as Raymond Lull) in his memoir The Invention of Solitude in the second part, The Book of Memory. Llull is also a major character in The Box of Delights, a children's novel by poet John Masefield.

Other recognition

editLlull's Art is sometimes recognized as a precursor to computer science and computation theory.[70] With the discovery in 2001 of his lost manuscripts, Ars notandi, Ars eleccionis, and Alia ars eleccionis, together known as Ars Magna (what today would be called a logical system to discover some sort of truth),[71] Llull is also given credit for creating an electoral system now known as the Borda count and Condorcet criterion, which Jean-Charles de Borda and Nicolas de Condorcet independently proposed centuries later.[72]

Translations

edit- Ramon Llull's New Rhetoric, text and translation of Llull's 'Rethorica Nova', edited and translated by Mark D. Johnston, Davis, California: Hermagoras Press, 1994

- Selected Works of Ramon Llull (1232‑1316), edited and translated by Anthony Bonner, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press 1985, two volumes XXXI + 1330 pp. (Contents: vol. 1: The Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men, pp. 93–305; Ars Demonstrativa, pp. 317–567; Ars Brevis, pp. 579–646; vol. 2: Felix: or the Book of Wonders, pp. 659–1107; Principles of Medicine pp. 1119–1215; Flowers of Love and Flowers of Intelligence, pp. 1223–1256)

- Doctor Illuminatus: A Ramon Llull Reader, edited and translated by Anthony Bonner, with a new translation of The Book of the Lover and the Beloved by Eve Bonner, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press 1994

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ Born 1232 per Mark D. Johnston in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (London: Routledge, 1998). Older sources (such as versions of Encyclopædia Britannica at least up to 1955) give 1235; the current Britannica gives 1232/33.

- ^ Variously latinized as Raimundus/Raymundus Lullus/Lulius/Lullius.

Citations

edit- ^ Frances Yates, "Lull and Bruno" (1982), in Collected Essays: Lull & Bruno, vol. I, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ^ a b The History of Philosophy, Vol. IV: Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to Leibniz by Frederick C. Copleston (1958).

- ^ Anthony Bonner (ed.), Doctor illuminatus: A Ramon Llull Reader, Princeton University Press, 1993, p. 82.

- ^ "Concession of Mass". newsaints.faithweb.com. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ Badia, Lola; Santanach, Joan; Soler, Albert (2016). Ramon Llull as a Vernacular Writer: Communicating a New Kind of Knowledge. Woodbridge: Tamesis.

- ^ Pereira, Michela (1989). The Alchemical Corpus attributed to Raymond Lull. London: The Warburg Institute.

- ^ George G. Szpiro, "Numbers Rule: The Vexing Mathematics of Democracy, from Plato to the Present" (2010).

- ^ Colomer, Josep M. (2013-02-01). "Ramon Llull: from 'Ars electionis' to social choice theory". Social Choice and Welfare. 40 (2): 317–328. doi:10.1007/s00355-011-0598-2. ISSN 1432-217X.

- ^ Bonner 2007, p. 290.

- ^ Donald Knuth (2006), The Art of Computer Programming: Generating all trees, vol. 4–4, Addison-Wesley Professional, p. 56, ISBN 978-0-321-33570-8

- ^ Bonner 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Llull, Ramon; Ramis Barceló, Rafael (2011). "Estudio preliminar". Arte de derecho (in Spanish). Editorial Dykinson. p. 17. ISBN 978-84-15454-34-2.

Ramon contrajo matrimonio con una mujer de su misma posición -Blanca Picany- y tuvieron dos hijos, Domènec y Magdalena.

- ^ Priani, Ernesto (2021). "Ramon Llull". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054.

In 1257 he married Blanca Picany, who belonged to another Catalan family settled in Majorca, with whom he had two children, Domènec and Magdalena.

- ^ Houssaye, Jean (2011). "Ramon Llull". Prémiers pedagogues: de l'Antiquité a la Renaissance (in French). Elsevier. p. 190. ISBN 978-2710115465.

Pendant cette même année 1257, il écrivit la Doctrina Pueril, son premiére grand ouvrage pédagogique, qu'il dédie à son fils, Domènec.

- ^ Fidora, Alexander (2020). "Ramon Llull: Doctrina Pueril". Kindlers Literatur Lexikon (in German). Springer. ISBN 978-3-476-05728-0.

Die pädagogisch-katechetische Abhandlung entstand 1274 bis 1276 vermutlich auf Mallorca. Das Werk, das Llull seinem Sohn Domènec widmete, [...]

- ^ "Cronologia". Any Llull (Generalitat de Catalunya – Institut Ramon Llull – Govern de les Illes Balears) (in Catalan). Year 1257. Archived from the original on 2016-04-10. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ "Biografia Ramon Llull". Associació d'Escriptors en Llengua Catalana (in Catalan). Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ Bonner, "Historical Background and Life" (an annotated Vita coaetanea) at 10–11, in Bonner (ed.), Doctor Illuminatus (1985).

- ^ Llull, Ramon (2010). A Contemporary Life, Edited and translated by Anthony Bonner. Barcelona/Woodbridge: Tamesis. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9781855661998.

- ^ Llull, Ramon (2010). A Contemporary Life, Edited and translated by Anthony Bonner. Barcelona/Woodbridge: Tamesis. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9781855661998.

- ^ Churchill, Leigh (2004). The Age of Knights & Friars, Popes & Reformers. Milton Keynes: Authentic Media. ISBN 1-84227-279-9, 9781842272794. p. 190

- ^ "Ermita de la Trinitat (Hermitage of the Holy Trinity) | Mallorca Guide, Tourist Attractions, Map". Mallorca Guide, Tourist Attractions, Map. 2019-01-12. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ Mark David Johnston (1996). The Evangelical Rhetoric of Ramon Llull: Lay Learning and Piety in the Christian West Around 1300. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-19-509005-5.

- ^ Blum, Paul Richard (28 June 2013). Philosophy of Religion in the Renaissance. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-1-4094-8071-6.

- ^ Paul Richard Blum: Philosophy of Religion in the Renaissance. Ashgate 2010, 1-14

- ^ ""Who was Ramon Llull?", Centre de Documentació Ramon Llull, Universitat de Barcelona". Archived from the original on 2013-03-13. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ^ Turner, William. "Raymond Lully." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 31 January 2019

- ^ a b Albrecht Classen (5 March 2018). Toleration and Tolerance in Medieval European Literature. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-1-351-00106-9.

- ^ Bonner, "Historical Background and Life" (the Vita coaetanea augmented and annotated) at 10-11, 34-37, in Bonner (ed.), Doctor Illuminatus (1985).

- ^ This Day In Jewish History | 1306: King Philip 'The Fair' Expels All France's Jews

- ^ Lower, Michael (2009). "Ibn al-Lihyani: sultan of Tunis and would-be Christian convert (1311–18)". Mediterranean Historical Review. 24 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1080/09518960903000744. S2CID 161432419.

- ^ Llull, Ramon (2010). A Contemporary Life, Edited and translated by Anthony Bonner. Barcelona/Woodbridge: Tamesis. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9781855661998.

- ^ "Basilica Sant Francesc", Illes Balears

- ^ a b Bonner 2007, p. 121.

- ^ Bonner 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Gayà, Jordi (1979). “La teoría luliana de los correlativos. Historia de su formación conceptual.” Universität Freiburg im Breisgau.

- ^ Pring-Mill, R.D.F. (1955). "The Trinitarian World Picture of Ramon Lull". Romanistisches Jahrbuch. 7: 229–256.

- ^ Link, David (2010). "Scrambling T-R-U-T-H: Rotating Letters as a Material Form of Thought", in: Variantology 4. On Deep Time Relations of Arts, Sciences and Technologies in the Arabic–Islamic World, eds. Siegfried Zielinski and Eckhard Fürlus (Cologne: König, 2010): 215–266

- ^ Lohr, Charles (1984). "Christianus arabicus, cuius nomen Raimundus Lullus". Freiburger Zeitschrift für Philosophie und Theologie. 31: 64–65.

- ^ Lohr, 1984, 63.

- ^ Lohr, Charles (1967). Raimundus Lullus' Compendium Logicae Algazelis. Quellen, Lehre und Stellung in der Geschichte der Logik. Thesis, Freiburg im Breisgau. pp. 93–130.

- ^ Friedlein, Roger (2004). Der Dialog bei Ramon Llull: Literarische Gestaltung als apologetische Strategie. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer. ISBN 3484523182.

- ^ van Steenberghen, Fernand (1960). "La signification de l'oeuvre anti-averroiste de Raymond Lull". Estudios Lulianos. 4: 113–28.

- ^ Imbach, Ruedi (1987). “Lulle face aux Averroïstes parisiens,” in Raymond Lulle et le pays d’Oc. Toulouse: Privat, pp. 261–82.

- ^ English translation by Yanis Dambergs: https://lullianarts.narpan.net/TreeOfScience/TreeOfScience-1.pdf and https://lullianarts.narpan.net/TreeOfScience/TreeOfScience2.pdf

- ^ Anthony Bonner, "The structure of the Arbor scientiae". Arbor Scientiae: der Baum des Wissens von Ramon Lull. Akten des Internationalen Kongresses aus Anlass des 40-jährigen Jubiläums des Raimundus-Lullus-Instituts der Universität Freiburg i. Br., ed. Fernando Domínguez Reboiras, Pere Villalba Varneda and Peter Walter, "Instrumenta Patristica et Mediaevalia. Subsidia Lulliana" 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002), pp. 21-34.

- ^ Dominguez, Fernando. "Felix Summary". Ramon Llull Database. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Hillgarth, J.N. (1971). Ramon Lull and Lullism in Fourteenth-century France. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Hillgarth, 1971, 269.

- ^ Colomer, Eusebio (1961). Nikolaus von Kues und Raimund Llull. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- ^ Hillgarth, 1971, 284

- ^ Lohr, Charles (1988). “Metaphysics.” In The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, edited by C. B. Schmitt, Quentin Skinner, Eckhard Kessler, and Jill Kraye, 537–638. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Ramis Barceló, Rafael (2019). "Academic Lullism from the Fourteenth to the Eighteenth Century," in A Companion to Ramon Llull and Lullism. Leiden: Brill, p. 458.

- ^ Pereira, Michela (1990). "Lullian Alchemy: Aspects and Problems of the corpus of Alchemical Works Attributed to Ramon Llull." Catalan Review, Vol. IV, 1-2: 41-54.

- ^ Yates, Frances (1964). Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 308-309.

- ^ Hillgarth 1971, 297.

- ^ M. Pereira, (1989), The alchemical corpus attributed to Raymond Lull, Warburg Institute, London. Pereira's inventory is currently maintained and expanded by the Base de Dades Ramon Llull project (Llull DB): http://www.ub.edu/llulldb/index.asp

- ^ Michela Pereira, (1987), “La leggenda di Lullo alchimista”, Estudios Lulianos, 27, pp. 145-163. Id., (2013), “Il santo alchimista. Intrecci leggendari attorno a Raimondo Lullo”, Micrologus, 21, pp. 471-515. Id., (2014), “Raimondo Lullo e l'alchimia: un mito tra storia e filologia”, Frate Francesco. Rivista di cultura francescana, 80, pp. 517-523.

- ^ Pereira & Spaggiari, (1999), Il Testamentum Alchemico, Edizioni del Galluzzo, Tavarnuzze

- ^ Azogue 9. Monograph on Alchemical Pseudolulism: https://revistaazogue.com/numero-9/

- ^ José Rodríguez Guerrero, “Nuevos Aportes para el Estudio del Liber de secretis naturae pseudoluliano”, Azogue, 9, 2019-2023, pp. 284-415.

- ^ Rubí, L. B. (2018). " Lullism among French and Spanish Humanists of the Early 16th Century". In A Companion to Ramon Llull and Lullism. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Ramis Barceló, R. (2018). "Chapter 12 Academic Lullism from the Fourteenth to the Eighteenth Century". In A Companion to Ramon Llull and Lullism. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Habig, Marion. (Ed.). (1959). The Franciscan Book of Saints. Franciscan Herald Press.

- ^ "RAIMVNDI LVLLI Opera latina". Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Nova Edició de les Obres de Ramon Llull (NEORL)". Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "SALVADOR DALÍ: ALCHIMIE DES PHILOSOPHES". Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Ramon Llull's Thinking Machine" in Borges, Jorge Luis (1999). Selected Non-fictions. New York: Viking. pp. 155–159.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1920). Limbo. Chatto & Windus.

- ^ Sales, Ton (2011). “Llull as Computer Scientist, or Why Llull Was One of Us.” In Ramon Llull. From the Ars Magna to Artificial Intelligence, edited by Alexander Fido and Carles Sierra. Barcelona: Artificial Intelligence Research Institute, 25–38.

- ^ Priani, Ernesto (2021), "Ramon Llull", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2023-10-05

- ^ G. Hägele & F. Pukelsheim (2001). "Llull's writings on electoral systems". Studia Lulliana. 41: 3–38. Archived from the original on 2006-02-07.

Sources

edit- Lola Badia, Joan Santanach and Albert Soler, Ramon Llull as a Vernacular Writer, London: Tamesis, 2016.

- Anthony Bonner (ed.), Doctor Illuminatus. A Ramon Llull Reader (Princeton University 1985), includes The Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men, The Book of the Lover and the Beloved, The Book of the Beasts, and Ars brevis; as well as Bonner's "Historical Background and Life" at 1–44, "Llull's Thought" at 45–56, "Llull's Influence: The History of Lullism" at 57–71.

- Bonner, Anthony (2007). The Art and Logic of Ramon Llull: A User's Guide. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16325-6.

- Umberto Eco (2016). "The Ars Magna by Ramon Llull". Contributions to Science. 12 (1): 47–50. doi:10.2436/20.7010.01.243. ISSN 2013-410X.

- Alexander Fidora and Josep E. Rubio, Raimundus Lullus, An Introduction to His Life, Works and Thought, Turnhout: Brepols, 2008.

- Mary Franklin-Brown, Reading the World: Encyclopedic Writing in the Scholastic Age, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- J. N. Hillgarth, Ramon Lull and Lullism in Fourteenth-Century France, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Mark D. Johnston, The Spiritual Logic of Ramón Llull, Oxford: Clarenden Press, 1987.

- Charles H. Lohr, “Ramon Lull's Theory of Scientific Demonstration,” in Argumentationstheorie, ed. Klaus Jacobi. Leiden: Brill, 1993, 729–46.

- Michela Pereira, The Alchemical Corpus attributed to Raymond Lull, London: The Warburg Institute, 1989.

- R. D. F. Pring-Mill, “The Trinitarian World Picture of Ramon Lull,” Romanistisches Jahrbuch 7 (1955): 229–256.

- Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966.

- Frances Yates, "Lull and Bruno" (1982), in Collected Essays: Lull & Bruno, vol. I, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

External links

edit- Works by Llull (OL 148354A) at the Open Library

- Works by Ramon Llull at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ramon Llull at the Internet Archive

- Priani, Ernesto. "Ramon Llull". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Who was Ramon Llull? Archived 2013-03-13 at the Wayback Machine Centre de Documentació Ramon Llull, Universitat de Barcelona

- Samuel M. Zwemer Raymund Lull: First Missionary to the Muslims

- Othmer MS 4 Ars brevis; Ars abbreviata praedicanda at OPenn

- Ramon Llull at the AELC (Association of Writers in Catalan Language). Webpage in Catalan, English and Spanish.

- "Ramon Llull". lletrA-UOC – Open University of Catalonia.

- Ramon Llull Database, University of Barcelona Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Catholic Encyclopedia article of 1911

- Blessed Raymond Lull

- Esteve Jaulent: The Theory of Knowledge and the Unity of Man according to Ramon Llull

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution portrait of Ramon Llull in .jpg and .tiff format.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ramon Llull", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Selected images from Practica compendiosa – The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library