Rattle and Hum is a hybrid live/studio album by Irish rock band U2, and a companion rockumentary film directed by Phil Joanou. The album was produced by Jimmy Iovine and was released on 10 October 1988, while the film was distributed by Paramount Pictures and was released on 27 October 1988. Following the breakthrough success of the band's previous studio album, The Joshua Tree, the Rattle and Hum project captures their continued experiences with American roots music on the Joshua Tree Tour, further incorporating elements of blues rock, folk rock, and gospel music into their sound. A collection of new studio tracks, live performances, and cover songs, the project includes recordings at Sun Studio in Memphis and collaborations with Bob Dylan, B. B. King, and Harlem's New Voices of Freedom gospel choir.

| Rattle and Hum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

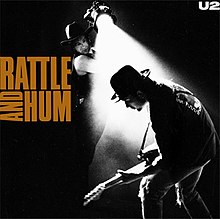

Artwork for compact disc release | ||||

| Studio album with live tracks by | ||||

| Released | 10 October 1988 | |||

| Recorded | 1987–1988 | |||

| Venue | Various locations | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Roots rock[1] | |||

| Length | 72:27 | |||

| Label | Island | |||

| Producer | Jimmy Iovine | |||

| U2 chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Rattle and Hum | ||||

| ||||

Although Rattle and Hum was intended to represent the band paying tribute to legendary musicians, some critics accused U2 of trying to place themselves amongst the ranks of such artists. Critical reception to both the album and the film was mixed; one Rolling Stone editor spoke of the album's "excitement"; another described it as "misguided and bombastic".[4] The film grossed just $8.6 million, but the album was a commercial success, reaching number one in several countries and selling 14 million copies. The lead single "Desire" became the band's first UK number-one song while reaching number three in the US.[5] Facing creative stagnation and a critical backlash to Rattle and Hum, U2 reinvented themselves in the 1990s through a new musical direction and public image.

History

edit"I was very keen on the idea of going wide at a time like that, just seeing how big this thing could get. I had always admired Colonel Parker and Brian Epstein for realising that music could capture the imagination of the whole world."

—U2 manager Paul McGuinness, explaining his original motivation to make a movie.[6]

While in Hartford during the Joshua Tree Tour in 1987, U2 met film director Phil Joanou who made an unsolicited pitch to the band to make a feature-length documentary about the tour. Joanou suggested they hire Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, or George Miller to direct the film. Joanou met the band again in Dublin to discuss the plans and again in France in September before the band chose him as director. The movie was originally titled U2 in the Americas and the band planned to film in Chicago and Buenos Aires later in the year.[7] It was later decided that the Chicago venue was not suitable, and instead U2 used the McNichols Sports Arena in Denver to film. Following the success of Live at Red Rocks: Under a Blood Red Sky, which had been filmed in Denver four years earlier, the band hoped that "lightning might strike twice".[8] With production problems and estimated costs of $1.2 million the band cancelled the plans for December concerts in South America. At the suggestions of concert promoter Barry Fey, the band instead booked Sun Devil Stadium at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona, the same city where the Joshua Tree Tour began.[8]

The movie is a rockumentary, which was initially financed by the band and intended to be screened in a small number of cinemas as an independent film. After going over budget, the film was bought by Paramount Pictures and released in theatres in 1988, before arriving on video in 1989. It was produced by Michael Hamlyn and directed by Joanou. Paul Wasserman served as the publicist.[9] It incorporates live footage with studio outtakes and band interviews. The album is a mix of live material and new studio recordings that furthers the band's experimentation with American music styles and recognises many of their musical influences. It was produced by Jimmy Iovine and also released in 1988.

The title, Rattle and Hum, is taken from a lyric from "Bullet the Blue Sky", the fourth track on The Joshua Tree. The image used for the album cover and movie poster, depicting Bono shining a spotlight on Edge as he plays, was inspired by a scene in the live performance of "Bullet the Blue Sky" recorded in the film and album, but was recreated in a stills studio and photographed by Anton Corbijn.[10] Several vinyl copies have the message "We Love You A.L.K." etched into side one, a reference to the band's production manager Anne Louise Kelly, who would be the subject of another secret dedication message on several CD copies of the band's later album, Pop.

Studio recordings

editBono said "Hawkmoon 269" was in part as a tribute to writer Sam Shepard, who had released a book entitled Hawk Moon. Bono also said that the band mixed the song 269 times. This was thought to be a joke for years until it was confirmed by guitarist the Edge in U2 by U2, who said that they spent three weeks mixing the song. He also contradicted Bono's assertion about Shepard, saying that Hawkmoon is a place in Rapid City, South Dakota, in the midwestern United States.[11]

"Angel of Harlem" is a horn-filled tribute to Billie Holiday. The bass-heavy "God Part II" is a sequel of sorts to John Lennon's "God".

The lead single, "Desire", sports a Bo Diddley beat. During the Joshua Tree tour, in mid-November 1987, Bono and Bob Dylan met in Los Angeles; together they wrote a song called "Prisoner of Love" which later became "Love Rescue Me". Dylan sang lead vocals on the original recording, a version which Bono called "astonishing", but Dylan later asked U2 not to use it citing commitments to The Traveling Wilburys.[12] The live performance of "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For" (recorded with a full church choir) is a gospel song. "When Love Comes to Town" is a blues rocker featuring B. B. King on guitar and vocals.

U2 recorded "Angel of Harlem", "Love Rescue Me" and "When Love Comes to Town" at Sun Studio in Memphis, Tennessee, where Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison, Johnny Cash and many others also recorded. They also recorded an unreleased version of "She's a Mystery to Me" and Woody Guthrie's "Jesus Christ", which appeared on Folkways: A Vision Shared. The band started writing "Heartland" in 1984 during The Unforgettable Fire sessions, and it was worked on during The Joshua Tree sessions.[13] All of the studio tracks apart from "Heartland" were performed in concert on the Lovetown Tour, which began almost a year after Rattle and Hum's release.

In addition to the nine studio tracks that comprised one half of the double album, a number of additional recordings from the Rattle and Hum sessions would be released on various singles and side projects. "Hallelujah Here She Comes" was released as a B-side to "Desire", and "A Room at the Heartbreak Hotel" was released as a B-side to "Angel of Harlem". Covers were released as B-sides for the rest of the singles—an abbreviated cover of Patti Smith's "Dancing Barefoot" would be released as a B-side to "When Love Comes to Town" (the full version would see release on the 12" version of the single and on CD on the 1994 soundtrack album to Threesome), while "Unchained Melody" and "Everlasting Love" would be released as the B-sides to "All I Want Is You". A cover of "Fortunate Son" recorded with Maria McKee would not be released until 1992's "Who's Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses" single; a version of the soul classic "Everybody Loves a Winner" by William Bell, also recorded with McKee, would eventually be released on the 20th anniversary edition of Achtung Baby.

Studio versions of "She's a Mystery to Me" (a Bono/Edge composition that would eventually be recorded and released by Roy Orbison), Bruce Cockburn's "If I Had a Rocket Launcher", Percy Sledge's "Warm and Tender Love", and "Can't Help Falling in Love With You", while recorded, have yet to be released. (A solo Bono cover of the Elvis Presley classic would be released on 1992's Honeymoon in Vegas album, however.) A cover of the Woody Guthrie song "Jesus Christ" was also recorded during these sessions for eventual inclusion on the cover album Folkways: A Vision Shared. Lastly, a cover of "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)" was recorded and released for the first A Very Special Christmas album, released at the end of 1987.

Live performances

editThe band chose to film the black-and-white footage over two nights at Denver's McNichols Sports Arena on 7 and 8 November 1987. They chose the city following the success of their U2 Live at Red Rocks: Under a Blood Red Sky video which was filmed in Red Rocks Amphitheatre near Denver in 1983. The Edge said, "We thought lightning might strike twice". The first night's performance disappointed the group, with Bono finding that the cameras infringed on his ability to play to the crowd.[8] The second Denver show was far more successful and seven songs from the show are used in the film, and three on the album.

Hours before the second Denver performance, an IRA bomb killed eleven people at a Remembrance Day ceremony in the Northern Irish town of Enniskillen (see Remembrance Day Bombing). During a performance of "Sunday Bloody Sunday", which appears on the film, Bono condemned the violence in a furious mid-song rant in which he yelled, "Fuck the revolution!" The performance was so powerful that the band said they were not sure the song should have been used in the film. After watching the film, they considered not playing the song on future tours.[14]

Colour outdoor concert footage is from the band's Tempe, Arizona shows on 19 and 20 December 1987. Tickets were sold for US$5 each and both nights sold out within days. The set was different each night with the band throwing in some rarely performed songs, including "Out of Control", "Christmas (Baby Please Come Home)", "One Tree Hill", and "Mothers of the Disappeared". For the latter, all four members played at the front of the stage, each under a large spotlight.

The album opens with a live cover of the Beatles' "Helter Skelter". Its inclusion on the album was intended by the band to reflect the confusion of The Joshua Tree Tour and their new-found superstar status. Bono opens "Helter Skelter" with this statement: "This is a song Charles Manson stole from the Beatles. We're stealing it back".[15]

The album contains a live version of Bob Dylan's "All Along the Watchtower". The performance is from the band's impromptu "Save the Yuppies" concert in Justin Herman Plaza in San Francisco, California on 11 November 1987. The video intersperses the performance of the song with footage from the band's performance of "Pride" from the same show, during which Bono spray-painted "Rock and Roll Stops the Traffic" on the Vaillancourt Fountain. This caused a bit of controversy, and ultimately, the band paid to repair the damage and publicly apologised for the incident. The phrase "Rock and Roll Stops the Traffic" reappeared 18 years later in the video "All Because of You" when an unnamed fan appeared with the sign at 1:55 in the video.[16] It also reappeared in February 2009, when the band played on the rooftop of the BBC Radio studios in Langham Place.[17]

Dennis Bell, director of New York gospel choir The New Voices of Freedom, recorded a demo of a gospel version of "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For".[18] While in Glasgow in late July during the Joshua Tree Tour, Rob Partridge of Island Records played the demo for the band.[19] In late September, U2 rehearsed with Bell's choir in a Harlem church, and a few days later they performed the song together at U2's Madison Square Garden concert. Footage of the rehearsal is featured in the movie, while the Madison Square Garden performance appears on the album.[20] After the church rehearsal, U2 walked around the Harlem neighbourhood where they came across blues duo, Satan and Adam, playing in the street. A 40-second clip of them playing their composition, "Freedom for My People", appears on both the movie and the album.[21]

During "Silver and Gold", Bono explains that the song is an attack on apartheid. "The Star Spangled Banner" is an excerpt of Jimi Hendrix's famous Woodstock performance in 1969. The noise of the crowd was sampled extensively by The KLF for 'the Stadium House Trilogy' of singles on their 1991 album The White Room.[22]

Alternative live concert footage captured for the film in other cities during the 1987 tour (but ultimately not used for the final cut of the film) included:

- Foxboro, Massachusetts, Foxboro Stadium, 22 September 1987

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, JFK Stadium, 25 September 1987

- New York, NY, Madison Square Garden, 28 September 1987

- Long Island, New York, Rehearsals on a beach, 19 October 1987

- Boston, Massachusetts, Boston Garden, 18 September 1987 (color footage)

Reception

editAlbum

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| The Arizona Republic | [23] |

| Austin American-Statesman | [24] |

| Chicago Sun-Times | [25] |

| The Cincinnati Enquirer | [26] |

| Knight-Ridder News | [27] |

| Los Angeles Times | [28] |

| New York Daily News | [29] |

| NME | 8/10[30] |

| Rolling Stone | [31] |

| The Village Voice | B+[32] |

The album divided critics when it was released in 1988.[33] Some reviewers panned it, feeling that U2 were making a deliberate and pretentious attempt at rock and roll renown.[30] Jon Pareles of The New York Times called it a "mess" that exuded "sincere egomania", and said the "band's self-importance got in the way" of their ambition for the album. He said it was plagued by the group's "attempts to grab every mantle in the Rock-and-Roll Hall of Fame" and that each one was "embarrassing in a different way".[34] David Stubbs of Melody Maker said that Rattle and Hum "lacks cohesion" and "is musically, stylistically confused". He criticised Bono's "reverential nods to the great white heroes of rock" and the band's "homages to the bluesmen and gospel greats".[35] Thom Duffy of the Orlando Sentinel said that Rattle and Hum is "greatly in need of a focal point" and "often sounds like an over-reaching attempt to claim chunks of pop history as [U2's] own story". He believed the group had "merely celebrated its own ascension into the pop history books... and little more".[36] Tom Carson from The Village Voice called it an "awful record" by "almost any rock-and-roll fan's standards", and said the group's failure did not "sound attributable to pretensions so much as to monumental know-nothingism".[37] Fellow Village Voice critic Robert Christgau was more complimentary, calling the record "looser and faster than anything they've recorded since their first live mini-LP".[32] David Browne of the New York Daily News said the album's "scope and disjointedness" recalled double albums such as Exile on Main St. or The Beatles, but that until it aged as well as those records, "'Rattle and Hum' just prattles and numbs".[29] Andrew Means of The Arizona Republic thought the album was "no substitute" for the "exhilaration and conviction" of the Joshua Tree Tour. He believed that Bono's passion on record was not "quite as mesmerizing as it is on stage" and that the group's new material did not "add significantly" to their message or image.[23] Lynden Barber of The Sydney Morning Herald called it "an ambitious project, and the result is almost inevitably a mixed bag". He lamented the songs that presented the band's Christianity "as a fait accompli", as well as their proclivity for "jams around a couple of chords substituting themselves for considered song-writing".[38] A reviewer for Knight-Ridder News said, "this double-album boondoggle manages to make the band sound like quintessential overreachers".[27]

Writing in Rolling Stone, Anthony DeCurtis said that the record succeeded at capping U2's rise to stardom "on a raucous, celebratory note", finding it to be "most enjoyable when the band relaxes and allows itself to stretch without self-consciously reaching for the stars". DeCurtis ultimately deemed it a "tad calculated in its supposed spontaneity" and said it demonstrated "U2's force but devot[ed] too little attention to the band's vision".[31] In a rave review for the Los Angeles Times, Robert Hilburn called Rattle and Hum a "frequently remarkable album" that more than matched The Joshua Tree, and he credited U2 for reviving the "idealism and craft of [rock's] finest moments".[28] J. D. Considine of The Baltimore Sun said that the album's songs "draw upon every musical strength U2 has developed over the years" and that the "sheer muscular physicality of its sound" set Rattle and Hum apart from its predecessors. He said that despite the record being "occasionally pretentious", the group "never seems out of its depth" amongst the guest artists.[39] Jay Cocks of Time said, "U2 has never sounded better or bolder", calling Rattle and Hum: "the best live rock album ever made. The record, in every sense, of their lives".[40] Hot Press reviewer Bill Graham said it was U2's "most ambitious record" yet,[41] while John Mackie of The Vancouver Sun said it "should consolidate the band's stature as the Beatles of the late '80s".[42] Cliff Radel of The Cincinnati Enquirer said that Rattle and Hum "proves the achievements of the band's previous album... were no accident", and that it demonstrated the group's ability to create "highly charged songs in the studio and on stage".[26] In the UK, Robin Denselow of The Guardian said that "the whole sounds far greater than the sum of the decidedly variable parts". The review found the cover songs to be the weakest material but judged Rattle and Hum overall to be a "solid, versatile piece of work" that "leaves much of the best until last".[43] Stuart Baillie of NME gave it a positive 8/10 review.[30] Contentiously, his review replaced a much more negative 4/10 review by Mark Sinker, in which he described it as "the worst album by a major band in years". It was pulled by NME editor Alan Lewis, as it was feared that criticism of U2 would affect the magazine's circulation;[44] Sinker resigned in protest.[30]

At the end of 1988, Rattle and Hum was voted the 21st-best album of the year in the Pazz & Jop, an annual poll of American critics published by The Village Voice.[45] In other critics' lists of the year's top albums, it was ranked number one by HUMO, second by the Los Angeles Times and Hot Press, 17th by OOR, 23rd by NME, and 47th by Sounds.[citation needed]

Film

edit"But I wasn't prepared for the difference in the size of the movie campaign and the average record campaign ... how all across America for a couple of weeks, you couldn't turn on your TV without getting U2 in your face. That's not the way records are marketed. It's much more subtle and I think a lot of the band's old fans found it distasteful. The aftermath I think, quite honestly, was that no one wanted to hear about U2 for a while."

—Paul McGuinness[46]

According to a USA Today survey of reviews at the time of the film's release, Rattle and Hum had an average review score of 64/100.[47] According to review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rating of 62%.[48] Roger Ebert panned the film as a "mess", saying the concert footage was poorly lit and did not show the audience enough, and that the band being "deliberately inarticulate" in interview segments was "not cute". His review partner Gene Siskel was more complimentary, praising the group's performance with the Harlem gospel choir as "powerful and emotional" and calling Bono's statements during "Sunday Bloody Sunday" the film's highlight.[49] Hal Hinson of The Washington Post called the film "an exercise in rock 'n' roll hagiography" and "a fanzine on celluloid", and said that despite its "stunning look", the film came across as "stagy and overproduced". He said that the band's "attempts to place themselves in the rock continuum are fairly strenuous and more than a little presumptuous".[50] Joyce Millman of the San Francisco Examiner described it as a "tediously pious and self-important" film that "successfully captured everything the faithful love, and we pagans loathe, about the biggest band of the '80s". She said the film "does nothing to pierce the band's vagueness" and that they were upstaged by King and the Harlem gospel choir. Millman judged that the cinematography's "gargantuan pomposity... perhaps unintentionally" personified "the essence of U2".[51] Gary Graff of the Detroit Free Press called the film "a conceptual mess that lacks focus and flow", and said that it neither chronicles the band's breakout success of 1987 adequately nor offers additional insight into the band. He said that "many of the individual components of [the film] are excellent" but that Joanou failed to tie them together.[52] Carrie Rickey of The Philadelphia Inquirer said, "Self-indulgent to the point of absurdity, U2 Rattle and Hum might be the silliest concert film ever made." She said it compared unfavourably to other concert movies due to its lack of narrative, and that Joanou's reverence for U2 bordered on "unintentional hilarity", adding, "Rob Reiner and company couldn't do a Spinal Tap on this; Rattle and Hum is already a parody."[53] Joanou himself called the picture "pretentious".[54]

Michael MacCambridge of the Austin American-Statesman disagreed with the film's detractors, calling it a "very good and at times excellent concert movie" whose "studied avoidance of drifting into self-parody" distinguished it from predecessors and headed off comparisons to This Is Spinal Tap. MacCambridge enjoyed the black-and-white footage of the band "in the middle of becoming legend" and their scenes with King and the Harlem gospel choir, but thought the switch to colour footage interrupted the film's "pace and momentum".[55] David Silverman of the Chicago Tribune said that Joanou "steadily brings the viewer into a relationship with the band and brings an understanding to the new music", while "provid[ing] an innovative, fast-paced insight" to U2. Silverman praised the documentary scenes with the individual band members and the "beautiful artistic" performance footage, and said the director "succeeded in bringing U2 to the screen in a creative, introspective and exciting film that will add to the legend and preserve the integrity of the decade's most influential contribution to rock".[56] Barbara Jaeger of The Record called it a "moving, beautifully photographed look at the group" that properly captured the energy of their live performances. She said, "If there is to be a standard against which future rock movies will be judged, 'U2 Rattle and Hum' is it."[57] Mackie of The Vancouver Sun said that despite the film offering "few insights into the individual members, the live footage is nothing short of brilliant." He described Bono's speech during "Sunday Bloody Sunday" as a "raw, emotional moment, a spontaneous outburst that crystalizes the powerful message of peace and love that U2 preach".[58] Michael Wilmington of the Los Angeles Times said the film "records some savagely compelling live performances" and offers proof of why "this unlikely band... are often ranked by critics as the world's best". He thought that despite Joanou not setting the proper context for the film or conducting an engaging interview with U2, "he matches the impassioned sounds with spectacular visuals".[59]

Commercial performance

editDespite the criticism, the Rattle and Hum album was a strong seller, continuing U2's burgeoning commercial success. It hit number one on the US Billboard 200 albums chart, remaining at the top spot for six weeks; it was the first number-one double album in the US since Bruce Springsteen's The River in 1980.[60] Rattle and Hum also reached number one in the UK and Australian charts. In the UK, it sold 360,000 copies in its first week, making it the fastest-selling album at that point (a record it held until the release of Oasis's Be Here Now in 1997).[61][62] Lifetime sales for the album have surpassed 14 million copies.[63]

Legacy

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [1] |

| Chicago Tribune | [64] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [65] |

| Entertainment Weekly | B[66] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [67] |

"Rattle and Hum was conceived as a scrapbook, a memento of that time spent in America on the Joshua Tree tour. It changed when the movie, which was initially conceived of as a low-budget film, suddenly became a big Hollywood affair. That put a different emphasis on the album, which suffered from the huge promotion and publicity, and people reacted against it."[68]

— The Edge

In 1989, while at a press tour in Sydney, Australia (where U2 were touring with B. B. King and working on demos for the follow-up album Achtung Baby), Bono stated, "making movies: that's the nonsense of rock & roll", which Rolling Stone magazine claimed was almost an apology for the film. "Playing shows is the reason we're here", he added.[69] Despite their commercial popularity, the group were dissatisfied creatively; Bono believed they were musically unprepared for their success, while Mullen said, "We were the biggest, but we weren't the best."[70] By the Lovetown Tour, they had become bored with playing their greatest hits.[71] U2 believe that audiences misunderstood the group's collaboration with King on Rattle and Hum and the Lovetown Tour, and they described it as "an excursion down a dead-end street".[72][73] Towards the end of the Lovetown Tour, Bono announced on-stage that it was "the end of something for U2", and that "we have to go away and ... dream it all up again".[73] The band subsequently reinvented themselves in the 1990s; beginning with Achtung Baby in 1991, they incorporated alternative rock, electronic dance music, and industrial music into their sound, and adopted a more ironic, flippant image by which they embraced the "rock star" identity they struggled with in the 1980s.[74]

Track listing

editAlbum

editAll lyrics are written by Bono; all music is composed by U2, except where noted

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Helter Skelter" (live at Denver, Colorado) | Lennon–McCartney (lyrics and music) | U2 | 3:07 |

| 2. | "Van Diemen's Land" | The Edge (lyrics) | U2 | 3:06 |

| 3. | "Desire" | U2 | 2:58 | |

| 4. | "Hawkmoon 269" | U2 | 6:22 | |

| 5. | "All Along the Watchtower" (live from "Save the Yuppie Free Concert", San Francisco) | Bob Dylan (lyrics and music) | U2 | 4:24 |

| 6. | "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For" (live at Madison Square Garden, New York) | U2 with The New Voices of Freedom | 5:53 | |

| 7. | "Freedom for My People" | Sterling Magee (lyrics and music); Adam Gussow (music) | Sterling Magee and Adam Gussow | 0:38 |

| 8. | "Silver and Gold" (live from Denver, Colorado) | U2 | 5:50 | |

| 9. | "Pride (In the Name of Love)" (live from Denver, Colorado) | U2 | 4:27 | |

| 10. | "Angel of Harlem" | U2 | 3:49 | |

| 11. | "Love Rescue Me" | Bono and Bob Dylan (lyrics) | U2 with Bob Dylan | 6:24 |

| 12. | "When Love Comes to Town" | U2 with B. B. King | 4:14 | |

| 13. | "Heartland" | U2 | 5:02 | |

| 14. | "God Part II" | U2 | 3:15 | |

| 15. | "The Star Spangled Banner" (live) | John Stafford Smith (music) | Jimi Hendrix | 0:43 |

| 16. | "Bullet the Blue Sky" (live at Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, Arizona) | U2 | 5:37 | |

| 17. | "All I Want Is You" | U2 | 6:30 | |

| Total length: | 72:27 | |||

Film

edit| U2: Rattle and Hum | |

|---|---|

| Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Phil Joanou |

| Produced by | Michael Hamlyn |

| Starring | U2 |

| Cinematography | Robert Brinkmann (black-and-white footage) Jordan Cronenweth (Color footage) |

| Edited by | Phil Joanou |

| Music by | U2 |

Production company | Midnight Films |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million |

| Box office | $8.6 million[75] |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Helter Skelter" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | Lennon–McCartney | U2 | |

| 2. | "Van Diemen's Land" (recorded at the Point Depot, Dublin, Ireland, May 1988[77]) | The Edge | U2 | |

| 3. | "Desire" (recorded at the Point Depot, Dublin, Ireland, May 1988[77]) | U2 | ||

| 4. | "Exit"/"Gloria" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | U2 ("Exit"), Van Morrison ("Gloria") | U2 | |

| 5. | "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For" (rehearsal recorded at Harlem, New York, September 1987[78]) | U2 with The New Voices of Freedom | ||

| 6. | "Freedom for My People" | Adam Gussow and Sterling Magee | Sterling Magee and Adam Gussow | |

| 7. | "Silver and Gold" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | Bono | U2 | |

| 8. | "Angel of Harlem" (recorded at Sun Studio, Memphis, Tennessee, 30 November 1987[79][80]) | U2 | ||

| 9. | "All Along the Watchtower" (live at Justin Herman Plaza, San Francisco, California, 11 November 1987[81]) | Bob Dylan | U2 | |

| 10. | "In God's Country" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | U2 | ||

| 11. | "When Love Comes to Town" (afternoon rehearsal and evening live performance at Tarrant County Convention Center, Fort Worth, Texas, 24 November 1987[82]) | U2 with B. B. King | ||

| 12. | "Heartland" | U2 | ||

| 13. | "Bad"/"Ruby Tuesday"/"Sympathy for the Devil" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | U2 ("Bad"), Jagger/Richards ("Ruby Tuesday", "Sympathy for the Devil") | U2 | |

| 14. | "Where the Streets Have No Name" (live at Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, Arizona, 20 December 1987[83]) | U2 | ||

| 15. | "MLK" (live at Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, Arizona, 20 December 1987[83]) | U2 | ||

| 16. | "With or Without You" (live at Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, Arizona, 19 December 1987[83]) | U2 | ||

| 17. | "The Star Spangled Banner" (Excerpt) | John Stafford Smith | Jimi Hendrix | |

| 18. | "Bullet the Blue Sky" (live at Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, Arizona, 20 December 1987[83]) | U2 | ||

| 19. | "Running to Stand Still" (live at Sun Devil Stadium, Tempe, Arizona, 20 December 1987[83]) | U2 | ||

| 20. | "Sunday Bloody Sunday" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | U2 | ||

| 21. | "Pride (In the Name of Love)" (live at McNichols Arena, Denver, Colorado, 8 November 1987[76]) | U2 | ||

| 22. | "All I Want Is You" (Heard over end credits) | U2 |

Personnel

edit- Bono – lead vocals, guitars, harmonica

- The Edge – guitars, keyboards, backing vocals, lead vocals on "Van Diemen's Land"

- Adam Clayton – bass guitar

- Larry Mullen Jr. – drums, percussion

Guest performers

- Bob Dylan – Hammond organ on "Hawkmoon 269", backing vocals on "Love Rescue Me"

- The New Voices of Freedom – gospel choir on "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For"

- George Pendergrass, Dorothy Terrell – vocal soloists

- Joey Miskulin – organ on "Angel of Harlem"

- The Memphis Horns – horns on "Angel of Harlem" and "Love Rescue Me"

- B. B. King – guest vocals and lead guitar on "When Love Comes to Town"

- Billie Barnum, Carolyn Willis, and Edna Wright – backing vocals on "Hawkmoon 269"

- Rebecca Evans Russell, Phyllis Duncan, Helen Duncan – backing vocals on "When Love Comes to Town"

- Brian Eno – keyboards on "Heartland"

- Benmont Tench – Hammond organ on "All I Want Is You"

- Van Dyke Parks – string arrangement on "All I Want Is You"

Additional musicians (field recordings and tapes)

- Satan and Adam (Sterling Magee and Adam Gussow) – vocals, guitar, percussion, and harmonica on "Freedom for My People" (sourced from field recording)

- Jimi Hendrix – electric guitar on "The Star Spangled Banner" (sourced from Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More as played through U2's concert PA system)

Charts

edit

Weekly chartsedit

|

Year-end chartsedit

|

Song charts

edit| Year | Song | Peak | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUS [107] |

CAN [108] |

IRE [109] |

NZ [107] |

UK [110] |

US Hot 100 [111][112] |

US Main Rock [111][112] | ||

| 1988 | "Desire" | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| "Angel of Harlem" | 18 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 1 | |

| "God Part II" | — | — | — | — | — | — | 8 | |

| 1989 | "When Love Comes to Town" | 23 | 41 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 68 | 2 |

| "All I Want Is You" | 2 | 67 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 83 | 13 | |

| "—" denotes a release that did not chart. | ||||||||

Certifications and sales

edit

Albumedit

|

Filmedit

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

editFootnotes

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Rattle and Hum – U2". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Music Week" (PDF). p. 40.

- ^ "Music Week" (PDF). p. 43.

- ^ Gardner, Elysa (9 January 1992). "U2's 'Achtung Baby': Bring the Noise". Rolling Stone. No. 621. p. 51. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 119

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 105

- ^ McGee (2008), pp. 105, 109

- ^ a b c McGee (2008), p. 112

- ^ "U2: Rattle and Hum (1988) – Full cast and crew". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Scrimgeour (2004), p. 273

- ^ McCormick (2006), p. 203

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 114

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 93

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 113

- ^ Graham (2004), p. 36

- ^ "U2 All Because of You". YouTube. 30 May 2006. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Jones, Sam (28 February 2009). "U2 attract 5,000 with rooftop homage to the Fab Four". The Guardian.

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 104

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 109

- ^ McGee (2008), pp. 110–111

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 111

- ^ "KLF Interview". cardhouse.com. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b Means, Andrew (25 October 1988). "Overshadowed by 'The Joshua Tree'". The Arizona Republic. pp. B6–B7.

- ^ MacCambridge, Michael (20 October 1988). "U2 twice as good on double album". Austin American-Statesman. p. C3.

- ^ McLeese, Don (17 October 1988). "Story of U2 album incomplete without film". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ a b Radel, Cliff (8 October 1988). "U2 settling score for Lennon". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. D1.

- ^ a b "In the Record Store". Times-Advocate. Knight-Ridder News. 3 November 1988. sec. North County magazine, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hilburn, Robert (9 October 1988). "U2 Embraces the Roots of Rock". Los Angeles Times. sec. Calendar, pp. 66, 68. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ a b Browne, David (9 October 1988). "U2 Prattles On". New York Daily News. sec. City Lights, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Jobling, John (2014). U2: The Definitive Biography. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-1-250-02790-0. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ a b DeCurtis, Anthony (17 November 1988). "U2's American Curtain Call". Rolling Stone. No. 539. p. 149. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (22 November 1988). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (20 November 1988). "The First Temptation of U2". Los Angeles Times. sec. Calendar, pp. 80, 86. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (16 October 1988). "When Self-Importance Interferes With the Music". The New York Times. p. H31. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Stubbs, David (15 October 1988). "The Lord's Prayer". Melody Maker. Vol. 64, no. 42. p. 37. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Thom (4 November 1988). "U2's sprawling 'Rattle and Hum' buzzes with self-congratulation". Orlando Sentinel. p. E-8. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Carson, Tom (15 November 1988). "Elvis is Alive!?". The Village Voice. Vol. 33, no. 46. p. 75.

- ^ Barber, Lynden (25 October 1988). "Lost amid the certainties". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 22.

- ^ Considine, J. D. (16 October 1988). "'Rattle and Hum': The Gospel According to U2". The Baltimore Sun. pp. 1M, 8M.

- ^ Cocks, Jay (21 November 1988). "Music: U2 Explores America". Time. Vol. 132, no. 21. pp. 146+. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Graham, Bill (20 October 1988). "Shake, Rattle and Hum". Hot Press. Vol. 12, no. 20. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Mackie, John (8 October 1988). "U2's new album confirms them as Beatles of the '80s". The Vancouver Sun. p. E12.

- ^ Denselow, Robin (7 October 1988). "A claim to the Hall of Fame". The Guardian. p. 33.

- ^ Dalton, Stephen (October 2003). "How the West Was Won". Uncut. No. 77.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (28 February 1989). "1988 Pazz & Jop: Dancing on a Logjam: Singles rool in a world up for grabs: The 15th (or 16th) annual Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (1 March 1992). "U2's U-Turn". Los Angeles Times. sec. Calendar, pp. 6–7, 76–77. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "The Movie Poll". USA Today. 11 November 1988. p. 4D.

- ^ "U2: Rattle and Hum (1988)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (host); Ebert, Roger (host) (5 November 1988). "Show 308". Siskel & Ebert. Episode 308. Buena Vista Television. Retrieved 24 March 2021 – via siskelebert.org.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (4 November 1988). "'U2': For Serious Fans Only". The Washington Post. p. B7. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Millman, Joyce (4 November 1988). "Oh, God". San Francisco Examiner. pp. C-1, C-9.

- ^ Graff, Gary (4 November 1988). "'U2: Rattle and Hum'". Detroit Free Press. pp. 1C, 4C.

- ^ Rickey, Carrie (4 November 1988). "Paying homage to the Irish band U2 on its recent tour". The Philadelphia Inquirer. sec. Weekend, p. 16.

- ^ Gardner (1994)

- ^ MacCambridge, Michael (4 November 1988). "Becoming a legend". Austin American-Statesman. p. F5.

- ^ Silverman, David (4 November 1988). "'Rattle and Hum' Introduces Personal Side of U2". Chicago Tribune. sec. 7, p. A. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Jaeger, Barbara (4 November 1988). "U2's power and intensity is captured on celluloid". The Record. sec. Previews, p. 29.

- ^ Mackie, John (4 November 1988). "U2 film catches live magic". The Vancouver Sun. p. C1.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (4 November 1988). "Movie Reviews: 'Rattle and Hum' Catches U2's Music and Message". Los Angeles Times. sec. Calendar, p. 6.

- ^ McGee (2008), p. 120

- ^ "10. U2: Rattle And Hum". Virgin Media. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Jones, Alan (8 December 2017). "Charts Analysis: Sam Smith surges to albums summit". Music Week. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ Stokes (2005), p. 78

- ^ Kot, Greg (6 September 1992). "You, Too, Can Hear The Best Of U2". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2007). "U2". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. p. 1426. ISBN 9781846098567.

- ^ Wyman, Bill (29 November 1991). "U2's Discography". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Considine, J. D.; Brackett, Nathan (2004). "U2". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 833–34. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony (December 2000). "U2's Edge and Adam Clayton Look Back on Two Decades of Hit Albums with Few – If Any – Regrets". Revolver.

- ^ "October 1989". Rolling Stone. No. 567/568. 14–28 December 1989. p. 127.

- ^ Fricke, David (1 October 1992). "U2 Finds What It's Looking For". Rolling Stone. No. 640. pp. 40+. Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Flanagan (1996), p. 4

- ^ Flanagan (1996), pp. 25, 27–28

- ^ a b McCormick (2006), p. 213

- ^ Dalton, Stephen (November 2004). "Achtung Stations". Uncut. No. 90. p. 52.

- ^ "U2: Rattle and Hum (1988)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, pp. 115-116

- ^ a b Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, p. 122

- ^ Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, p. 113

- ^ Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, p. 119

- ^ Peter Williams and Steve Turner, 1988, U2: Rattle and Hum: The Official Book of the U2 Movie, pp. 46-47. The Sun Studio session was on a Monday night, later on the same day as the Graceland footage was filmed, between the 28 November gig at Murfreesboro and the 3 December gig at Miami. In 1987, this was 30 November.

- ^ Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, pp. 116-117

- ^ Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, p. 118

- ^ a b c d e Pimm Jal de la Parra, 1994, U2 Live: A Concert Documentary, pp. 120-121

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – U2 – Rattle And Hum" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – U2 – Rattle And Hum" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – U2 – Rattle And Hum" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Charts.nz – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – U2 – Rattle And Hum". Hung Medien. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "U2 Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 1988". austriancharts.at. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1988". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 1989". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 1989". austriancharts.at. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1989". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1989". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1989". hitparade.ch. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1989". Billboard. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b "1ste Ultratop-hitquiz". Ultratop. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^

- "RPM100 Singles" (PDF). RPM. Vol. 49, no. 5. 19 November 1988. p. 6.

- "RPM100 Singles" (PDF). RPM. Vol. 49, no. 16. 13–18 February 1989. p. 6.

- "RPM100 Singles" (PDF). RPM. Vol. 50, no. 2. 8–13 May 1989. p. 6.

- "RPM100 Singles" (PDF). RPM. Vol. 50, no. 13. 24–29 July 1989. p. 6.

- ^ "Search the charts". Irishcharts.ie. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2009. Note: U2 must be searched manually

- ^ "U2 singles". Everyhit.com. Retrieved 29 October 2009. Note: U2 must be searched manually.

- ^ a b "U2: Charts and Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ a b "U2 songs". Billboard. Retrieved 29 October 2009. Note: Songs must be searched manually

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 1996 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hun" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum". Music Canada. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ a b "A Celebration" (PDF). Music & Media. 4 March 1989. p. 7. Retrieved 24 November 2019 – via American Radio History.

- ^ a b "U2" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "French album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum" (in French). InfoDisc. Select U2 and click OK.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (U2; 'Rattle and Hum')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "IFPIHK Gold Disc Award − 1989". IFPI Hong Kong. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Caroli, Daniele (9 December 1989). "Italy > Talent Challenges" (PDF). Billboard Magazine. 101 (49). Nielsen Business Media, Inc.: I-8. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 26 July 2020 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Retrieved 26 July 2020. Enter Rattle and Hum in the "Artiest of titel" box. Select 1988 in the drop-down menu saying "Alle jaargangen".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Tenente, Fernando (14 April 1990). "INTERNATIONAL: Floyd, Kaoma Top Sellers In Portugal Certs" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 102, no. 15. p. 69. Retrieved 28 November 2020 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Sólo Éxitos 1959–2002 Año A Año: Certificados 1979–1990 (in Spanish), Iberautor Promociones Culturales, 2005, ISBN 8480486392

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Rattle and Hum')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "British album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "American album certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Springer, Matt (22 November 2013). "Top 10 Covers of Beatles 'White Album' Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank ('Rattle and Hum')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "British video certifications – U2 – Rattle and Hum". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

Bibliography

- Graham, Bill; van Oosten de Boer, Caroline (2004). U2: The Complete Guide to Their Music. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-9886-8.

- McGee, Matt (2008). U2: A Diary. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84772-108-2.

- Stokes, Niall (2005). U2: Into the Heart – The Stories Behind Every Song. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-765-2.

- Scrimgeour, Diana (2004). U2 Show. London: Orion Books. ISBN 0-7528-5607-3.

- U2 (2006). McCormick, Neil (ed.). U2 by U2. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-719668-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

edit- Rattle and Hum at U2.com

- Soundtrack of Rattle and Hum at IMDb

- Rattle and Hum at AllMovie

- Rattle and Hum at Discogs (list of releases)