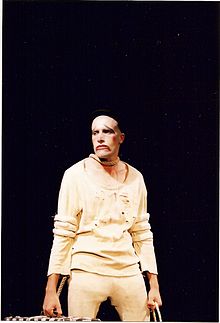

Lucky is a character from Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot. He is a slave to the character Pozzo.[1]

Lucky is unique in a play where most of the characters talk incessantly: he only utters two sentences, one of which is more than seven hundred words long (the monologue). Lucky suffers at the hands of Pozzo willingly and without hesitation. He is "tied" (a key theme in Godot) to Pozzo by a ridiculously long rope in the first act, and then a similarly ridiculous short rope in the second act.[2] Both tie around his neck. When he is not serving Pozzo, he usually stands in one spot drooling, or sleeping if he stands there long enough. His props include a picnic basket, a coat, and a suitcase full of sand.

Interpretation

editLucky's place in Waiting for Godot has been heavily debated. Even his name is somewhat elusive. Some have marked him as "lucky" because he is "lucky in the context of the play." He does not have to search for things to occupy his time, which is a major pastime of the other characters. Pozzo tells him what to do, he does it, and is therefore lucky because his actions are determined absolutely. Beckett asserted, however, that he is lucky because he has "no expectations".[citation needed]

Lucky and Vladimir

editLucky is often compared to Vladimir (just as Pozzo is compared to Estragon) as being the intellectual, left-brained part of his character duo (i.e. he represents one part of a larger, whole character, whose other half is represented by Pozzo). Read this way, Pozzo and Lucky are simply an extreme form of the relationship between Estragon and Vladimir (the hapless impulsive and the intellect who protects him). He philosophises, like Vladimir, and is integral to Pozzo's survival, especially in the second act. In the second act, Lucky becomes mute. Pozzo mourns this, despite the fact that it was he who silenced Lucky in the first act.

The monologue

editLucky is most famous for his speech in Act I. The monologue is prompted by Pozzo when the tramps ask him to make Lucky "think". He asks them to give him his hat: when Lucky wears his hat, he is capable of thinking. The monologue is long, rambling word salad, and does not have any apparent end; it is only stopped when Vladimir takes the hat back. Within the gibberish Lucky makes comments on the arbitrary nature of God, man's tendency to pine and fade away, and towards the end, the decaying state of the earth. His ramblings may be loosely based around the theories of the Irish philosopher Bishop Berkeley.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ Times, The New York (2007-10-30). The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge, Second Edition: A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind. Macmillan. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-312-37659-8.

- ^ Listengarten, Julia (2000). Russian Tragifarce: Its Cultural and Political Roots. Susquehanna University Press. pp. 171–173. ISBN 978-1-57591-033-8.