Lidia Zamenhof (Esperanto: Lidja Zamenhofo; 29 January 1904–1942) was a Jewish Polish writer, publisher, translator and the youngest daughter of Klara (Silbernik) and L. L. Zamenhof, the creator of Esperanto. She was an active promoter of Esperanto as well as of Homaranismo, a form of religious humanism first defined by her father.

Lidia Zamenhof | |

|---|---|

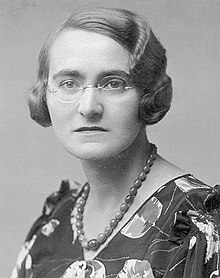

Lidia Zamenhof before the Nazi German invasion of Poland | |

| Born | 29 January 1904 |

| Died | 1942 (aged 37–38) |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Other names | Lidja |

| Known for | Activity in Esperanto movement and Baháʼí Faith |

| Parent(s) | L. L. Zamenhof (1859–1917) Klara Zamenhof (1863–1924) |

Around 1925 she became a member of the Baháʼí Faith.[1] In late 1937 she went to the United States to teach that religion as well as Esperanto. In December 1938 she returned to Poland, where she continued to teach and translated many Baháʼí writings.[2] She was murdered at the Treblinka extermination camp during the Holocaust.[3]

Life

editLidia Zamenhof learned Esperanto as a nine-year-old girl. By the age of fourteen, she translated from Polish literature; her first publications appeared several years thereafter. Having completed her university studies in law in 1925, she dedicated herself totally to working for Esperanto. In the same year during the 17th World Congress of Esperanto in 1925 in Geneva she became acquainted with the Baháʼí Faith. Lidia Zamenhof became secretary of the homaranistic Esperanto-Society Concord in Warsaw and often made arrangements for speakers and courses. Starting at the Vienna World Congress of Esperanto in 1924 she attended almost every World Congress (she missed the 1938 Universala Kongreso in England). As an instructor of the Cseh method of teaching Esperanto she made many promotional trips and taught many courses in various countries.

She actively coordinated her work with the student Esperanto movement — in the International Student League, in the UEA, in the Cseh Institute, and in the Baháʼí Faith. Additionally, Lidia wrote for the journal Literatura Mondo (mainly studies on Polish Literature), and also contributed to Pola Esperantisto, La Praktiko, Heroldo de Esperanto, and Enciklopedio de Esperanto. Her translation of Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz was published in 1933 and is very well known.

In 1937 she went to the United States for a long stay. In December 1938 she had to leave the United States because that country's Immigration Service declined to extend her tourist visitor's visa because of her allegedly illegal "paid labor" of teaching Esperanto. She refused offers of marriage that could have permitted her to remain or eventually to naturalize. After returning to Poland, her homeland, she travelled around the country teaching Esperanto and the Baháʼí Faith.

Under the German occupation regime of 1939, her home in Warsaw became part of the Warsaw Ghetto. She was arrested under the charge of having gone to the United States to spread anti-Nazi propaganda,[4] but after a few months, she was released and returned to her home city where she and the rest of her family remained confined. There she endeavored to help others get medicine and food. She was offered help and escape several times by Polish Esperantists but refused in each case. To one Pole, well-known Esperantist Józef Arszennik, who had offered her refuge on several occasions, she explained, "you and your family could lose your lives because whoever hides a Jew perishes along with the Jew who is discovered."[5][6] To another, her explanation was contained in her last known letter: "Do not think of putting yourself in danger; I know that I must die but I feel it is my duty to stay with my people. God grant that out of our sufferings a better world may emerge. I believe in God. I am a Baháʼí and will die a Baháʼí. Everything is in His hands."[7]

Eventually in the end she was swept up in the mass transport heading to the extermination camp in Treblinka in the course of the Grossaktion Warsaw. She was killed there sometime after the summer of 1942.[8]

Memorial

editIn her memory and honor, a meeting was held in 1995 at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The meeting called attention to Esperantists' efforts to save persecuted Jews during World War II.[citation needed]

Esperanto works

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). "Zamenhof, Lidia". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 368. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ "Famous Baha'is". adherents.com. 2005-12-06. Archived from the original on October 19, 2000. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Lidia Zamenhof, a cosmopolitan woman and victim of the Holocaust". blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ Heller, Wendy Lidia, The Life of Lidia Zamenhof Daughter of Esperanto, 1985, pp. 234-235

- ^ Joanna Iwaszkiewicz, Wtedy Kwitły Forsycje, 1993, pp.113

- ^ "Getto Warszawskie". Archived from the original on 2014-12-14.

- ^ Heller, Wendy Lidia, The Life of Lidia Zamenhof Daughter of Esperanto, 1985, pg. 240

- ^ "Lidia Zamenhof, a cosmopolitan woman and victim of the Holocaust". blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

References

edit- In English: Wendy Heller, Lidia: The Life of Lidia Zamenhof, Daughter of Esperanto.

- In Esperanto: Wendy Heller, Lidia: La vivo de Lidia Zamenhof, filino de Esperanto (ISBN 978-90-77066-36-2)

- In Esperanto: Isaj Dratwer, Lidia Zamenhof. Vivo kaj agado

- An extensive chapter on Lidia Zamenhof in La familio Zamenhof, by Zofia Banet-Fornalowa.

- Information about Lidia Zamenhof may be found in publications of the Baháʼí Esperanto movement and in other articles.

- As of August 2006, most of this article is a translation of the corresponding Esperanto Vikipedio article.

Drama

editThe documentary drama Ni vivos! (We will live!) by Julian Modest depicts the Zamenhof family's fate in the Warsaw Ghetto.

External links

edit- Works by Lidia Zamenhof at Faded Page (Canada)

- (in English) John Dale - Notes on the life of Lidia Zamenhof

- (in Esperanto) Esperanto Translations by Lidia Zamenhof and Roan Orloff Stone Translations of several important Baháʼí writings in Esperanto.