Peter Press Maravich (/ˈmɛərəˌvɪtʃ/ MAIR-ə-vitch; June 22, 1947 – January 5, 1988), known by his nickname Pistol Pete, was an American professional basketball player. He starred in college at Louisiana State University's Tigers basketball team; his father, Press Maravich, was the team's head coach. Maravich is the all-time leading NCAA Division I men's scorer with 3,667 points scored and an average of 44.2 points per game.[1] All of his accomplishments were achieved before the adoption of the three-point line and shot clock, and despite being unable to play varsity as a freshman under then-NCAA rules.[2]

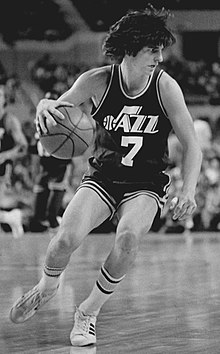

Maravich was selected by the Atlanta Hawks in the 1970 NBA draft, playing four seasons for the team. He was traded to the New Orleans Jazz, then an expansion team, with whom he spent the majority of the rest of his career. His final season was split between the Jazz and the Boston Celtics. Injuries ultimately forced Maravich's retirement in 1980 following a 10-year professional basketball career. He was named an All-Star five times and was named to four All-NBA Teams during his professional career.

One of the youngest players ever inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, Maravich was considered to be one of the greatest creative offensive talents ever and one of the best ball handlers of all time.[3][4] He died suddenly at age 40 during a pick-up game in 1988 as a consequence of an undetected heart defect.[5] Maravich was named to the NBA's 50th Anniversary team in 1996 and 75th Anniversary team in 2021.

Early life

editMaravich was born to Petar "Press" Maravich (1915–1987) and Helen Gravor Maravich (1925–1974) in Aliquippa, a steel town in Beaver County in western Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh.[1] Maravich amazed his family and friends with his basketball abilities from an early age. He enjoyed a close but demanding father-son relationship that motivated him toward achievement and fame in the sport. Maravich's father was the son of Serbian immigrants[6] and a professional player–turned-coach. He showed his son the fundamentals starting when Pete was seven years old. Obsessively, young Maravich spent hours practicing ball control tricks, passes, head fakes, and long-range shots.[7]

Maravich played high school varsity ball at Daniel High School in Central, South Carolina, a year before being old enough to attend the school. While at Daniel from 1961 to 1963, Maravich participated in the school's first-ever game against a team from an all-black school. In 1963 his father departed from his position as head basketball coach at Clemson University and joined the coaching staff at North Carolina State University.[1] While living in Raleigh, North Carolina, Maravich attended Needham B. Broughton High School, where his famous moniker was born. From his habit of shooting the ball from his side, as if holding a revolver, Maravich became known as "Pistol" Pete Maravich.[1]: 78 He graduated from Broughton in 1965[8] and then attended Edwards Military Institute, where he averaged 33 points per game. It was known that Press Maravich was extremely protective of Maravich and would guard against any issue that might come up during his adolescence; Press threatened to shoot Maravich with a .45-caliber pistol if he drank or got into trouble.[1] Maravich was 6 feet 4 inches in high school and was getting ready to play in college when his father took a coaching position at Louisiana State University.[1]

College career

editAt that time NCAA rules prohibited first-year students from playing at varsity level, which required Maravich to play on the freshman team. In his first game, Maravich put up 50 points, 14 rebounds and 11 assists against Southeastern Louisiana College.[5]

In only three years playing on the varsity team (and under his father's coaching) at LSU, Maravich scored 3,667 points—1,138 of those in 1967–68, 1,148 in 1968–69, and 1,381 in 1969–70—while averaging 43.8, 44.2, and 44.5 points per game, respectively. For his collegiate career, the 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m) guard averaged 44.2 points per game in 83 contests and led the NCAA in scoring for each of his three seasons.[9]

Maravich's long-standing collegiate scoring record is particularly notable when three factors are taken into account:[10]

- First, because of the NCAA rules that prohibited him from taking part in varsity competition during his first year as a student, Maravich was prevented from adding to his career record for a full quarter of his time at LSU. During this first year, Maravich scored 741 points in freshman competition.[11]

- Second, Maravich played before the advent of the three-point line. This significant difference has raised speculation regarding just how much higher his records would be, given his long-range shooting ability and how such a component might have altered his play. Writing for ESPN.com, Bob Carter stated, "Though Maravich played before [...] the 3-point shot was established, he loved gunning from long range."[12] It has been reported that former LSU coach Dale Brown charted every shot Maravich scored and concluded that, if his shots from three-point range had been counted as three points, Maravich's average would have totaled 57 points per game[13][14] and 12 three-pointers per game.

- Third, the shot clock had also not yet been instituted in NCAA play during Maravich's college career. (A time limit on ball possession speeds up play, mandates an additional number of field goal attempts, eliminates stalling, and increases the number of possessions throughout the game, all resulting in higher overall scoring.)[15]

More than 50 years later, however, many of his NCAA and LSU records still stand. Maravich was a three-time All-American. Though he never appeared in the NCAA tournament, Maravich played a key role in turning around a lackluster program that had posted a 3–20 record in the season prior to his arrival. Maravich finished his college career in the 1970 National Invitation Tournament, where LSU finished fourth.[2]

NCAA career statistics

edit| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

Freshman

editAt this time, freshmen did not play on the varsity team and these stats do not count in the NCAA record books.

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966–67 | Louisiana State | 19 | 19 | ... | .452 | ... | .833 | 10.4 | ... | ... | ... | 43.6 |

Varsity

edit| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967–68 | Louisiana State | 26 | 26 | ... | .423 | ... | .811 | 7.5 | 4.0 | ... | ... | 43.8 |

| 1968–69 | Louisiana State | 26 | 26 | ... | .444 | ... | .746 | 6.5 | 4.9 | ... | ... | 44.2 |

| 1969–70 | Louisiana State | 31 | 31 | ... | .447 | ... | .773 | 5.3 | 6.2 | ... | ... | 44.5 |

| Career[16] | 83 | 83 | ... | .438 | ... | .775 | 6.5 | 5.1 | ... | ... | 44.2 | |

Professional basketball career

editAtlanta Hawks

editThe Atlanta Hawks selected Maravich with the third pick in the first round of the 1970 NBA draft, where he played for coach Richie Guerin.[17] He was not a natural fit in Atlanta. The Hawks already boasted a top-notch scorer at the guard position in combo guard Lou Hudson. In fact, Maravich's flamboyant style stood in stark contrast to the conservative play of Hudson and star center Walt Bellamy. It also did not help that many of the veteran players resented the $1.9 million contract that Maravich received from the team—a very large salary at that time.[18]

Maravich appeared in 81 games and averaged 23.2 points per contest—good enough to earn NBA All-Rookie Team honors. He managed to blend his style with his teammates, so much so that Hudson set a career high by scoring 26.8 points per game. But the team stumbled to a 36–46 record—12 wins fewer than in the previous season. Still, the Hawks qualified for the playoffs, where they lost to the New York Knicks during the first round, as Maravich averaged 22 points a contest in the five-game series.[19][20]

Maravich struggled somewhat during his second season. His scoring average dipped to 19.3 points per game, and the Hawks finished with another disappointing 36–46 record. Once again they qualified for the playoffs, and once again they were eliminated in the first round. However, Atlanta fought hard against the Boston Celtics, with Maravich averaging 27.7 points in the series.[20]

Maravich erupted in his third season, averaging 26.1 points (fifth in the NBA) and dishing out 6.9 assists per game (sixth in the NBA). With 2,063 points, he combined with Hudson (2,029 points) to become only the second set of teammates in league history to each score over 2,000 points in a single season.[a] The Hawks soared to a 46–36 record, but again bowed out in the first round of the playoffs. However, the season was good enough to earn Maravich his first-ever appearance in the NBA All-Star Game, and also All-NBA Second Team honors.[20]

The following season (1973–74) was his best yet—at least in terms of individual accomplishments. Maravich posted 27.7 points per game—second in the league behind Bob McAdoo—and earned his second appearance in the All-Star Game, where he would start for the Eastern Conference and score 15 points.[21] However, Atlanta sank to a disappointing 35–47 record and missed the postseason entirely.

New Orleans Jazz

editIn the summer of 1974, the expansion New Orleans Jazz franchise was preparing for its first season of competition in the NBA and were looking to generate excitement among their new basketball fans. With his exciting style of play, Maravich was seen as the perfect man for the job. Additionally, he was already a celebrity in the state due to his accomplishments at LSU. To acquire Maravich, the Jazz traded two players and four draft picks to Atlanta.[20][22]

The expansion team struggled mightily in its first season. Maravich managed to score 21.5 points per game, but shot a career-worst 41.9 percent from the floor. The Jazz posted a 23–59 record, worst in the NBA.[20]

Jazz management did its best to give Maravich a better supporting cast. The team posted a 38–44 record in its second season (1975–76) but did not qualify for postseason play despite the dramatic improvement. Maravich struggled with injuries that limited him to just 62 games that season, but he averaged 25.9 points per contest (third behind McAdoo and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and continued his crowd-pleasing antics. He was elected to the All-NBA First Team that year.[20]

The following season (1976–77) was his most productive in the NBA. He led the league in scoring with an average of 31.1 points per game. He scored 40 points or more in 13 games,[b] and 50 or more in four games.[c] His 68-point masterpiece against the Knicks[23][24] was at the time the most points ever scored by a guard in a single game, and only two players at any position had ever scored more: Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor.[25] Coincidentally, Baylor was head coach of the Jazz at that time. Despite Maravich's performance, the team finished at 35–47 (three wins shy of the previous season) and once again failed to make the playoffs.

Maravich earned his third All-Star game appearance and was honored as All-NBA First Team for the second consecutive season.[20]

The following season, injuries to both knees forced him to miss 32 games during the 1977–78 season.[20] Despite being robbed of some quickness and athleticism, he still managed to score 27.0 points per game, and he also added 6.7 assists per contest, his highest average as a member of the Jazz. Many of those assists went to new teammate Truck Robinson,[citation needed] who had joined the franchise as a free agent during the off-season. In Robinson's first year in New Orleans, Robinson averaged 22.7 points and a league-best 15.7 rebounds per game.[26] Robinson's presence prevented opponents from focusing their defensive efforts entirely on Maravich,[20] and it lifted the Jazz to a 39–43 record—just short of making the club's first-ever appearance in the playoffs.

Knee problems plagued Maravich for the rest of his career. He played in just 49 games during the 1978–79 season. He scored 22.6 points per game that season and earned his fifth and final All-Star appearance, but his scoring and passing abilities were severely impaired.[20] The team struggled on the court, and faced serious financial trouble as well. Management became desperate to make some changes. The Jazz traded Robinson to the Phoenix Suns, receiving draft picks and some cash in return.[27] However, in 1979, team owner Sam Battistone moved the Jazz to Salt Lake City.[20]

Final season

editThe Utah Jazz began play in the 1979–80 season. Maravich moved with the team to Salt Lake City, but his knee problems were worse than ever. He appeared in 17 games early in the season, but his injuries prevented him from practicing much, and new coach Tom Nissalke had a strict rule that players who didn't practice were not allowed to play in games. Thus, Maravich was parked on the bench for 24 straight games, much to the dismay of Utah fans and to Maravich himself.[28] During that time, Adrian Dantley emerged as the team's franchise player.

The Jazz placed Maravich on waivers in January 1980.[29] He signed with the Celtics, the top team in the league that year, led by rookie superstar Larry Bird.[30] Maravich adjusted to a new role as part-time contributor, giving Boston a "hired gun" on offense off the bench. He helped the team post a 61–21 record in the regular season, the best in the league. And, for the first time since his early career in Atlanta, Maravich was able to participate in the NBA playoffs. He appeared in nine games during that postseason, but the Celtics were upended by Julius Erving and the Philadelphia 76ers in the Eastern Conference finals, four games to one.[31][32]

Realizing that his knee problems would never go away, Maravich retired at the end of that season.[33] The NBA instituted the 3-point shot just in time for Maravich's last season in the league.[20] He had always been famous for his long-range shooting, and though injury-dampened, his final year provided an official statistical gauge of his abilities. Between his limited playing time in Utah and Boston, he made 10 of 15 3-point shots,[20] giving him a career 66.7% completion rate.

During his ten-year career in the NBA, Maravich played in 658 games, averaging 24.2 points and 5.4 assists per contest. In 1987, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, and his No. 7 jersey has been retired by both the Jazz and the New Orleans Pelicans, as well as his No. 44 jersey by the Atlanta Hawks. In 2021, to commemorate the NBA's 75th Anniversary The Athletic ranked their top 75 players of all time, and named Maravich as the 73rd greatest player in NBA history.[34]

NBA career statistics

edit| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| * | Led the league |

Regular season

edit| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–71 | Atlanta | 81 | — | 36.1 | .458 | — | .800 | 3.7 | 4.4 | — | — | 23.2 |

| 1971–72 | Atlanta | 66 | — | 34.9 | .427 | — | .811 | 3.9 | 6.0 | — | — | 19.3 |

| 1972–73 | Atlanta | 79 | — | 39.1 | .441 | — | .800 | 4.4 | 6.9 | — | — | 26.1 |

| 1973–74 | Atlanta | 76 | — | 38.2 | .457 | — | .826 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 1.5 | .2 | 27.7 |

| 1974–75 | New Orleans | 79 | — | 36.1 | .419 | — | .811 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 1.5 | .2 | 21.5 |

| 1975–76 | New Orleans | 62 | — | 38.3 | .459 | — | .811 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 1.4 | .4 | 25.9 |

| 1976–77 | New Orleans | 73 | — | 41.7 | .433 | — | .835 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 1.2 | .3 | 31.1* |

| 1977–78 | New Orleans | 50 | — | 40.8 | .444 | — | .870 | 3.6 | 6.7 | 2.0 | .2 | 27.0 |

| 1978–79 | New Orleans | 49 | — | 37.2 | .421 | — | .841 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 1.2 | .4 | 22.6 |

| 1979–80 | Utah | 17 | — | 30.7 | .412 | .636 | .820 | 2.4 | 3.2 | .9 | .2 | 17.1 |

| Boston | 26 | 4 | 17.0 | .494 | .750 | .909 | 1.5 | 1.1 | .3 | .1 | 11.5 | |

| Career | 658 | — | 37.0 | .441 | .667 | .820 | 4.2 | 5.4 | 1.4 | .3 | 24.2 | |

| All-Star | 4 | 4 | 19.8 | .409 | — | .778 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 10.8 | |

Playoffs

edit| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Atlanta | 5 | — | 39.8 | .377 | — | .692 | 5.2 | 4.8 | — | — | 22.0 |

| 1972 | Atlanta | 6 | — | 36.5 | .446 | — | .817 | 5.3 | 4.7 | — | — | 27.7 |

| 1973 | Atlanta | 6 | — | 39.0 | .419 | — | .794 | 4.8 | 6.7 | — | — | 26.2 |

| 1980 | Boston | 9 | — | 11.6 | .490 | .333 | .667 | .9 | .7 | .3 | .0 | 6.0 |

| Career[16] | 26 | — | 29.1 | .423 | .333 | .784 | 3.6 | 3.8 | .3 | .0 | 18.7 | |

Later life and death

editAfter injuries forced his retirement from the game in 1980, Maravich became a recluse for two years. Through it all, Maravich said he was searching "for life". He tried the practices of yoga and Hinduism, read Trappist monk Thomas Merton's The Seven Storey Mountain and took an interest in the field of ufology, the study of unidentified flying objects. He also explored vegetarianism and macrobiotics, adopting a vegetarian diet in 1982.[35]

Eventually, he became a born-again Christian, embracing evangelical Christianity. A few years before his death, Maravich said, "I want to be remembered as a Christian, a person that serves [Jesus] to the utmost, not as a basketball player."[36]

On January 5, 1988, Maravich collapsed and died of heart failure at age 40[37] while playing in a pickup basketball game in the gym at First Church of the Nazarene in Pasadena, California, with a group that included evangelical author James Dobson. Maravich had flown out from his home in Covington, Louisiana, to tape a segment for Dobson's radio show that aired later that day. Dobson has said that Maravich's last words, less than a minute before he died, were "I feel great."[38]

An autopsy revealed the cause of death to be a rare congenital defect: the left coronary artery, a vessel that supplies blood to the muscle fibers of the heart, was missing. His right coronary artery was grossly enlarged and had been compensating for the defect.[39]

Maravich was survived by his wife, Jackie, and their sons Jaeson, then 8 years old, and Josh, then 5 years old.[40][41]

Maravich's children were very young when he died and Jackie Maravich (also known as Jackie McLachlan) initially shielded them from unwanted media attention, not even allowing Jaeson and Josh to attend their father's funeral.[15] However, his sons still developed a love for the game. During a 2003 interview, Jaeson told USA Today that, when he was still only a toddler, "My dad passed me a (Nerf) basketball, and I've been hooked ever since ... My dad said I shot and missed, and I got mad and I kept shooting. He said his dad told him he did the same thing."[42]

Despite some setbacks coping with their father's death and without the benefit that his tutelage might have provided, both sons eventually were inspired to play high school and collegiate basketball—Josh at his father's alma mater, LSU.[42][43]

On June 7, 2024, Josh Maravich died in the family home in Covington, Louisiana, at 42 years old.[33][44][45]

Legacy

editOn June 27, 2014, Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal proposed that LSU erect a statue of Maravich outside the Pete Maravich Assembly Center. Jackie McLachlan said that she had been promised a statue after the passing of her husband.[46] Others opposed a Maravich statue because he had fallen a few credits short of graduation and therefore didn't meet the requirements for monuments to student-athletes.[47] Magic Johnson admitted to taking the "Showtime" name from Maravich as well as studying all his moves.[48] Meanwhile, Bob Dylan wrote of idolizing Pete Maravich when he was playing for New Orleans.[49]

In February 2016, the LSU Athletic Hall of Fame Committee unanimously approved a proposal that a statue honoring Maravich be installed on the campus, revising the stipulations required.[50] On July 25, 2022, the statue was unveiled to the public outside of the Assembly Center.[51][52]

Memorabilia

editMaravich's untimely death and mystique have made memorabilia associated with him among the most highly prized of any basketball collectibles. Game-used Maravich jerseys bring more money at auction than similar items from anybody other than George Mikan, with the most common items selling for $10,000 and up and a game-used LSU jersey selling for $94,300 in a 2001 Grey Flannel auction.[53] The signed game ball from his career-high 68-point night on February 25, 1977, sold for $131,450 in a 2009 Heritage auction.[54]

Honors, books, films and music

edit- In 1970, during his LSU days, Acapulco Music/The Panama Limited released "The Ballad of Pete Maravich" by Bob Tinney and Woody Jenkins.

- In 1987, roughly a year before his death, Maravich co-authored Heir to a Dream, an award-winning (Gold Medallion) autobiography, with Darrel Campbell. It devotes considerable focus to his life after retirement from basketball and his later devotion to Christianity.

- In 1987, Maravich and Campbell produced the four-episode basketball instructional video series Pistol Pete's Homework Basketball.

- In 1988, Frank Schroeder and Darrel Campbell produced the documentary Maravich Memories: The LSU Years, based on Maravich's college career.

- After Maravich's death, Louisiana Governor Buddy Roemer signed a proclamation officially renaming LSU's basketball court the Pete Maravich Assembly Center.

- Bob Dylan wrote about the day he heard Maravich died in his memoir, Chronicles: Volume One. The news startled him, bringing back memories of the time Maravich made a deep impression on him when he saw Maravich play in New Orleans. Referring to him as "the holy terror of the basketball world" and a "magician of the court," Dylan added that "Pistol Pete hadn’t played professionally for a while, and he was thought of as forgotten. I hadn’t forgotten about him, though. Some people seem to fade away but then when they are truly gone, it’s like they didn’t fade away at all." Dylan then remembers that it was in the early afternoon, when news of Maravich's death began to wear away, that he started writing a new song called "Dignity."[55] Though it would remain unreleased for several years, many would regard it as one of Dylan's greatest compositions from that era.[56]

- In 1991, The Pistol: The Birth of a Legend, a biographical film written and produced by Darrel Campbell dramatizing Maravich's 8th-grade season, was released.[57]

- In 1996, Maravich was named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History by a panel made up of NBA historians, players, and coaches. He was the only deceased player on the list. At the ceremony during halftime for the 1997 All-Star Game in Cleveland, he was represented by his two sons.

- Alternative rock band Smashing Pumpkins mentions "Pistol Pete" in their song "The Tale of Dusty and Pistol Pete".[58]

- In 2001, a comprehensive 90-minute documentary film, Pistol Pete: The Life and Times of Pete Maravich, debuted on CBS.

- In 2005, rapper Lil Wayne mentioned Maravich in his song "Best Rapper Alive."

- In 2005, ESPNU named Maravich the greatest college basketball player of all time.

- In 2007, two biographies of Maravich were released: Maravich by Wayne Federman and Marshall Terrill; and Pistol by Mark Kriegel. Also in 2007, to promote Kriegel's book, Fox Sports conducted a contest to find "Pete Maravich's Biggest Fan". The winner was Scott Pollack of Sunrise, Florida.

- In 2021, Maravich was named one of the members of the NBA 75th Anniversary Team by a panel made up of NBA historians, players and coaches.

- The Ziggens, a band from Southern California, wrote "Pistol Pete", a song about Maravich.[59]

- Hip-hop artist Aesop Rock mentions "Pistol Pete" in his song "Citronella".[60]

Collegiate awards and records

editAwards

- The Sporting News College Player of the Year (1970)

- USBWA College Player of the Year (1969, 1970)

- Naismith Award Winner (1970)

- Helms Foundation Player of the Year (1970)

- UPI Player of the Year (1970)

- Sporting News Player of the Year (1970)

- AP College Player of the Year (1970)

- The Sporting News All-America First Team (1968, 1969, 1970)

- Three-time AP and UPI First-Team All-America (1968, 1969, 1970)

- Led the NCAA Division I in scoring with 43.8 ppg (1968); 44.2 (1969) and 44.5 ppg (1970)

- Averaged 43.6 ppg on the LSU freshman team (1967)

- Scored a career-high 69 points vs. Alabama (February 7, 1970); 66 vs. Tulane (February 10, 1969); 64 vs. Kentucky (February 21, 1970); 61 vs. Vanderbilt (December 11, 1969)

- Holds LSU records for most field goals made (26) and attempted (57) in a game against Vanderbilt on January 29, 1969

- All-Southeastern Conference (1968, 1969, 1970)

- #23 Jersey retired by LSU (2007)

- In 1970, Maravich led LSU to a 20–8 record and a fourth-place finish in the National Invitation Tournament

Records

- Highest scoring average, points per game, career: 44.2 (3,667 points/83 games)

- Points, season: 1,381 (1970)

- Highest scoring average, points per game, season: 44.5 (1,381/31) (1970)

- Games scoring 50 or more points, career: 28

- Games scoring 50 or more points, season: 10 (1970)

- Field goals made, career: 1,387

- Field goals made, season: 522 (1970)

- Field goal attempts, career: 3,166

- Field goal attempts, season: 1,168 (1970)

- Free throws made, game: 30 (in 31 attempts), vs. Oregon State, December 22, 1969

- Tied by Ben Woodside, North Dakota State, on December 6, 2008[61]

NBA awards and records

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2023) |

- NBA All-Rookie Team

- All-NBA First Team (1976, 1977)

- All-NBA Second Team (1973, 1978)

- Five-time NBA All-Star (1973, 1974, 1977, 1978, 1979)

- Led the league in scoring (31.1 ppg) in 1977, his career best

- Scored a career-high 68 points against the New York Knicks on February 25, 1977

- #7 jersey retired by the Utah Jazz (1985)[62]

- #7 jersey retired by the Superdome (1988)

- NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team (1996)

- NBA 75th Anniversary Team (2021)

- #7 jersey retired by the New Orleans Hornets (now Pelicans) (2002),[62] even though he never played for them—one of only four players to have a number retired by a team they did not play for; Maravich did play professionally for the New Orleans Jazz, however, and has remained a greatly admired figure amongst New Orleans sports fans ever since.

- #44 jersey retired by the Atlanta Hawks (2017)[62]

Free throws made, quarter: 14, Pete Maravich, third quarter, Atlanta Hawks vs. Buffalo Braves, November 28, 1973

- Broken by Vince Carter on December 23, 2005[63]

Free throw attempts, quarter: 16, Pete Maravich, second quarter, Atlanta Hawks at Chicago Bulls, January 2, 1973

- Broken by Ben Wallace on December 11, 2005[64]

Second pair of teammates in NBA history to score 2,000 or more points in a season: 2, Atlanta Hawks (1972–73)

Maravich: 2,063

Lou Hudson: 2,029

Third pair of teammates in NBA history to score 40 or more points in the same game: New Orleans Jazz vs. Denver Nuggets, April 10, 1977

Maravich: 45

Nate Williams: 41

David Thompson of the Denver Nuggets also scored 40 points in this game.

Ranks 4th in NBA history – Free throws made, none missed, game: 18–18, Pete Maravich, Atlanta Hawks vs. Buffalo Braves, November 28, 1973

Ranks 5th in NBA history – Free throws made, game: 23, Pete Maravich, New Orleans Jazz vs. New York Knicks, October 26, 1975 (2 OT)

See also

edit- List of individual National Basketball Association scoring leaders by season

- List of National Basketball Association players with most points in a game

- List of National Basketball Association top rookie scoring averages

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball players with 60 or more points in a game

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball season scoring leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball career scoring leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball career free throw scoring leaders

- List of National Basketball Association annual minutes leaders

References

editNotes

- ^ Elgin Baylor and Jerry West were the first to accomplish this feat in the Los Angeles Lakers' 1964–65 season. It has since accomplished only three times: back-to-back by Kiki Vandeweghe and Alex English of the 1982–1984 Denver Nuggets, and by Larry Bird and Kevin McHale of the 1986–87 Boston Celtics.

- ^ At the time, Tiny Archibald's 18 games of 40+ points in 1972–73 was the only total higher by a guard.

- ^ The most ever by a guard, until Michael Jordan did it eight times in 1986–87. Jordan would go on to get four or more 50+ point games in three more seasons; Kobe Bryant is the only other guard to reach this mark, six times in 2005–06, and a record ten times in 2006–07.

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f Schroeder, Frank; Campbell, Darrel; Maravich, Pete (1987). Heir to a Dream. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 0840776098.

- ^ a b "Peter Maravich". Hoophall.com. Basketball Hall of Fame. March 10, 2019. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "What If——-Pete Maravich?". Thomaston Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Hall of Famers". Hoophall.com. Basketball Hall of Fame. January 5, 1988. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Federman, Wayne; Terrill, Marshall; Maravich, Jackie (2006). Maravich. Sport Classic Books. p. 68. ISBN 1-894963-52-0.

- ^ Kriegel 2007, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Kriegel 2007, pp. 285–297.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Center for the Book". pabook.libraries.psu.edu. Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Thomas (January 6, 1988). "Pete Maravich, a Hall of Famer Who Set Basketball Marks, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- ^ Yusuf, Farouk (March 6, 2024). ""Comparing apples to oranges": LSU HC Kim Mulkey subtly downplays Caitlin Clark's historic feat of breaking Pete Maravich's scoring record". Sportkeeda. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Kriegel 2007, p. 325.

- ^ Medcalf, Myron (August 18, 2014). "What if 'Pistol' Pete had a 3-point line?". ESPN.com. ESPN. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Diaz, Angel; Erwin, Jack; Warner, Ralph (March 2, 2012). "The 25 Most Unbreakable Records in Sports History". Complex.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Steve Bunin, Bill Walton (2006). Remembering Pete Maravich (Television production). The Hot List. Event occurs at 1:56. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Thamel, Pete (February 17, 2004). "In the Name of His Father: The Journey of Pete Maravich's Son". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2009. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "Pete Maravich NBA Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "1970 NBA Draft". DatabaseBasketball.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ "Pete Maravich Bio". nba.com. NBA. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "1971 NBA Eastern Conference Semifinals Hawks vs. Knicks". basketball-reference.com. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Legends profile: Pete Maravich". NBA.com. Retrieved February 20, 2024.

- ^ "1974 NBA All-Star Game". Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Benson, Pat (May 20, 2022). "May 20, 1974: Hawks Trade Pete Maravich to Jazz". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry (November 19, 2003). "Pete Maravich's 68 points a record". ESPN.go.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "'Pistol' Pete Maravich – Career Recap". LSUsports.net. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Most points by 1 player in a NBA game, 50 point games in NBA history". NBAhoopsonline.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Kostecka, Ryan (November 27, 2023). "Jazz Basketball Decade Series: 1970s". nba.com.

- ^ Papanek, John (January 29, 1979). "The Truck Stops Here". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Federman & Terrill 2008, pp. 316–326.

- ^ "Maravich Is Waived by Jazz; Statement by Owners". The New York Times. January 18, 1980.

- ^ Linda Hamilton (November 2, 2004). "25 years later the Jazz are going strong". Deseret.news.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Connelly, Michael (2010). Rebound!: Basketball, Busing, Larry Bird, and the Rebirth of Boston. Voyageur Press. p. 230. ISBN 9781616731472.

- ^ "Pete Maravich Playoffs Game Log". basketball reference.

- ^ a b "Ex-LSU player Josh Maravich, son of Hall of Fame player Pete Maravich, dead at age 42". MSN. Associated Press. June 8, 2024.

- ^ Dodd, Rustin (November 3, 2021). "NBA 75: At No. 73, 'Pistol' Pete Maravich was a prodigy, offensive showman, fearless visionary". The Athletic. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ Carter, Bob (2007). "Maravich's creative artistry dazzled". Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ Federman, p. 367

- ^ "Maravich Is Eulogized". The New York Times. January 10, 1988. Archived from the original on February 10, 2024. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Pete Maravich Predicted His Future In 1974". OpenCourt-Basketball. February 11, 2017. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ "Pete Maravich was born with a rare heart defect". pistolpete23.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012.

- ^ Kriegel 2007, p. 299.

- ^ "Former LSU Basketball Player Josh Maravich Passes Away". lsusports.net. June 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Weir, Tom (February 14, 2003). "Playing in Pistol Pete's shadow". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Josh Maravich Stats, Bio". ESPN. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "Ex-LSU player Maravich, son of Pete, dies at 42". ESPN.com. June 9, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ "Josh Maravich, son of LSU and NBA legend 'Pistol Pete,' dies at 42". www.fox8live.com. June 8, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ Michelle Millhollon (June 27, 2014). "Jindal to LSU: How about a statue of Pete Maravich?". The Advocate. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ "LSU board to revise policy blocking Pete Maravich statue". WBRZ-TV. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ "'Pistol' Pete Maravich: An NBA Legacy Carried on 25 Years After". Bleacher Report. January 10, 2013.

- ^ Cochran, Jeff (May 10, 2023). "Pete Maravich and Bob Dylan: Courting Dignity".

- ^ "LSU will add statue of 'Pistol' Pete Maravich outside of arena named in his honor". The Times-Picayune. February 8, 2016. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "Unveiling of the Pete Maravich statue is set. When will it debut outside the PMAC?". The Advocate. June 22, 2022. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Pete Maravich statue unveiled on LSU's campus along side other Tiger greats". WBRZ-TV. July 25, 2022. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Demand for Pistol Pete memorabilia is stronger tha". Sports Collectors Digest. December 21, 2007. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ "1977 Pete Maravich Sixty-Eighth Point Game Used Basketball Basketball Collectibles: Balls". sports.ha.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Dylan, B., (2004), Chronicles: Volume One. Simon & Schuster. p. 168-169

- ^ "Bob Dylan's 20 Best Songs of the '80s". spectrumculture.com. September 4, 2020. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021.

- ^ "The Pistol: The Birth of a Legend". pistolmovie.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014.

- ^ The Tale of Dusty and Pistol Pete

- ^ "Pistol Pete – The Ziggens". Songmeanings.net. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ Aesop Rock – Citronella, archived from the original on September 27, 2023, retrieved September 27, 2023

- ^ "Remember the Name: Ben Woodside". ESPN. ESPN. December 15, 2008. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Which NBA players have had their jersey retired by multiple franchises?". www.sportingnews.com. January 13, 2022. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ New Jersey Nets vs. Miami Heat – Play By Play – December 23, 2005 – ESPN (4th quarter) NB: While this link only backs up the fact that Carter made 16 free throws in a quarter, there is no mention of any records broken or set.

- ^ Detroit Pistons vs. Los Angeles Clippers – Recap – December 11, 2005 – ESPN NB: While this link only backs up the fact that Wallace attempted 20 free throws in a quarter, there is no mention of any records broken or set.

Further reading

edit- Campbell, Darrel (2019). Hero & Friend: My Days with Pistol Pete. Percussion Films. ISBN 978-0-578-21343-9.

- Berger, Phil (1999). Forever Showtime: The Checkered Life of Pistol Pete Maravich. Taylor Trade. ISBN 0-87833-237-5.

- Federman, Wayne; Terrill, Marshall (2007). Maravich. SportClassic Books. ISBN 978-1-894963-52-7.

- Federman, Wayne; Terrill, Marshall (2008). Pete Maravich: The Authorized Biography of Pistol Pete. Focus on the Family/Tyndale House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58997-535-4.

- Gutman, Bill (1972). Pistol Pete Maravich: The making of a basketball superstar. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 0-448-01973-6.

- Kriegel, Mark (2007). Pistol: The Life of Pete Maravich. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-8497-4.

- Maravich, Pete and Campbell, Darrel (1987). Heir To A Dream. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 0-8407-7609-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Towle, Mike (2000). I Remember Pete Maravich. Nashville: Cumberland House. ISBN 1-58182-148-4.

- Towle, Mike (2003). Pete Maravich: Magician of the Hardwood. Nashville: Cumberland House. ISBN 1-58182-374-6.

- Brown, Danny (2008). Shooting the Pistol: Courtside Photographs of Pete Maravich at LSU. Louisiana State University Press ISBN 978-0-8071-3327-9

External links

edit- Official website

- Pete Maravich biography at NBA.com

- Pete Maravich at ESPN

- Pete Maravich at Find a Grave

- Pete Maravich's Greatest Achievement at powertochange.ie

- ‘68 All College MVP - 4 Days with Pistol Pete at Oklahoman.com

- Pete Maravich Bio LSU Tigers Athletics Archived February 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine