Myelin basic protein (MBP) is a protein believed to be important in the process of myelination of nerves in the nervous system. The myelin sheath is a multi-layered membrane, unique to the nervous system, that functions as an insulator to greatly increase the velocity of axonal impulse conduction.[5] MBP maintains the correct structure of myelin, interacting with the lipids in the myelin membrane.[6][7]

| Myelin_MBP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Myelin_MBP | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01669 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000548 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00492 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1bx2 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 274 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 2lug | ||||||||

| |||||||||

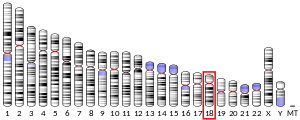

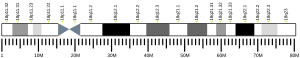

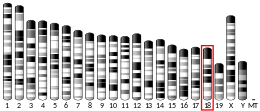

MBP was initially sequenced in 1971 after isolation from bovine myelin membranes.[8] MBP knockout mice called shiverer mice were subsequently developed and characterized in the early 1980s. Shiverer mice exhibit decreased amounts of CNS myelination and a progressive disorder characterized by tremors, seizures, and early death. The human gene for MBP is on chromosome 18;[9] the protein localizes to the CNS and to various cells of the hematopoietic lineage.

The pool of MBP in the central nervous system is very diverse, with several splice variants being expressed and a large number of post-translational modifications on the protein, which include phosphorylation, methylation, deamidation, and citrullination. These forms differ by the presence or the absence of short (10 to 20 residues) peptides in various internal locations in the sequence. In general, the major form of MBP is a protein of about 18.5 Kd (170 residues).

In melanocytic cell types, MBP gene expression may be regulated by MITF.[10]

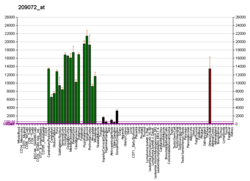

Gene expression

editThe protein encoded by the classic MBP gene is a major constituent of the myelin sheath of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells in the nervous system. However, MBP-related transcripts are also present in the bone marrow and the immune system. These mRNAs arise from the long MBP gene (otherwise called "Golli-MBP") that contains three additional exons located upstream of the classic MBP exons. Alternative splicing from the Golli and the MBP transcription start sites gives rise to two sets of MBP-related transcripts and gene products. The Golli mRNAs contain three exons unique to Golli-MBP, spliced in-frame to one or more MBP exons. They encode hybrid proteins that have an N-terminal Golli amino acid sequence linked to the MBP amino acid sequence. The second family of transcripts contains only MBP exons and produces the well-characterized myelin basic proteins. This complex gene structure is conserved among species, suggesting that the MBP transcription unit is an integral part of the Golli transcription unit and that this arrangement is important for the function and/or regulation of these genes.[11] At protein level, the concentration of MBP in the CNS is tenfold higher in sections of white matter compared with cerebral cortex.[12]

Structure

editMyelin basic protein has been classified as an intrinsically disordered protein that has no stable secondary structure in solution.[13] Like most IDPs, it has a high net charge and a low mean hydrophobicity, minimizing the hydrophobic effect that drives traditional protein folding. It does contain some exceptions to normal IDP amino acid content. For example, MBP has more arginine and less glutamic acid than most IDPs. However, this is likely because those changes are necessary for MBP to be sufficiently basic and positively charged to correctly interact with the membrane.[14] Notably, MBP has been shown to adopt a more stable secondary structure on interaction with lipids.[15][16] NMR and Cys-specific spin labeling experiments have predicted this structure to contain beta sheet and regions of amphipathic helix.[17]

As implied by its name, myelin basic protein is significantly basic, with an isoelectric point of 10. It is thought to associate with the cell membrane through electrostatic interactions between its positive charges and negatively charged phospholipid heads of the plasma membrane.[18] It can undergo a large variety of post-translational modifications, creating various charge isomers known as C1-C6 or C8.[19] These modifications include phosphorylation, methylation, deamidation, citrullination, ADP-ribosylation, and N-terminal acylation . C1 is the least modified, while C8 is the most distinct, containing 6-11 additional citrullinations. Since each of these decreases its positive charge, C8 has the smallest net positive charge of the isomers. Alternations in these post-translational modifications have been associated with demyelinating diseases. Notably, MBP isolated from individuals with multiple sclerosis have had a higher degree of citrullination and a smaller positive charge. In a rare, severe form of MS known as Marburg's syndrome, the citrullination was even more extensive.[18]

Role in disease

editInterest in MBP has centered on its role in demyelinating diseases, in particular, multiple sclerosis (MS). The target antigen of the autoimmune response in MS has not yet been identified. However, several studies have shown a role for antibodies against MBP in the pathogenesis of MS.[20] Some studies have linked a genetic predisposition to MS to the MBP gene, though a majority have not.

A "molecular mimicry" hypothesis of multiple sclerosis has been suggested, in which T cells are, in essence, confusing MBP with human herpesvirus-6. Researchers in the United States created a synthetic peptide with a sequence identical to that of an HHV-6 peptide. Elevated levels of MBP have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with HIV infections and signs of encephalopathy, and although MBP does not seem to be a sensitive diagnostic marker of HIV encephalopathy, it has been suggested that it may serve a role as a prognostic indicator of disease progression.[21] It is able to show that T cells were activated by this peptide. These activated T cells also recognized and initiated an immune response against a synthetically created peptide sequence that is identical to part of human MBP. During their research, they found that the levels of these cross-reactive T cells are significantly elevated in multiple sclerosis patients.[22]

Some research has shown that inoculating an animal with MBP to generate an MBP-specific immune response against it increases blood–brain barrier permeability. Permeability is enhanced when the animal is inoculated against non-specific proteins.[23]

A targeted immune response to MBP has been implicated in lethal rabies infection. The inoculation of MBP generates increases the permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), allowing immune cells to enter the brain, the primary site of rabies virus replication. In a study of mice infected with Silver-haired bat rabies virus (SHBRV), the mortality rate of mice treated with MBP improved 20%-30% over the untreated control group. It is significant to note that healthy uninfected mice treated with MBP showed an increase in mortality rate between 0% and 40%.[24]

Interactions

editMyelin basic protein has been shown to interact in vivo with proteolipid protein 1,[25][26] and in vitro with calmodulin, actin, tropomyosin, tubulin, clathrin, 2',3'-cyclic-nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase and multiple molecules of the immune system.[27]

References

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000197971 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000041607 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Sakamoto Y, Kitamura K, Yoshimura K, Nishijima T, Uyemura K (March 1987). "Complete amino acid sequence of PO protein in bovine peripheral nerve myelin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (9): 4208–4214. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61334-1. PMID 2435734.

- ^ Deber CM, Reynolds SJ (April 1991). "Central nervous system myelin: structure, function, and pathology". Clinical Biochemistry. 24 (2): 113–134. doi:10.1016/0009-9120(91)90421-a. PMC 7130177. PMID 1710177.

- ^ Inouye H, Kirschner DA (January 1991). "Folding and function of the myelin proteins from primary sequence data". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 28 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1002/jnr.490280102. PMID 1710279. S2CID 8598890.

- ^ Eylar EH, Brostoff S, Hashim G, Caccam J, Burnett P (September 1971). "Basic A1 protein of the myelin membrane. The complete amino acid sequence". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 246 (18): 5770–5784. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61872-1. PMID 5096093.

- ^ Saxe DF, Takahashi N, Hood L, Simon MI (1985). "Localization of the human myelin basic protein gene (MBP) to region 18q22----qter by in situ hybridization". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 39 (4): 246–249. doi:10.1159/000132152. PMID 2414074.

- ^ Hoek KS, Schlegel NC, Eichhoff OM, Widmer DS, Praetorius C, Einarsson SO, et al. (December 2008). "Novel MITF targets identified using a two-step DNA microarray strategy". Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 21 (6): 665–676. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00505.x. PMID 19067971. S2CID 24698373.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: myelin basic protein".

- ^ Sjölin K, Kultima K, Larsson A, Freyhult E, Zjukovskaja C, Alkass K, Burman J (June 2022). "Distribution of five clinically important neuroglial proteins in the human brain". Molecular Brain. 15 (1): 52. doi:10.1186/s13041-022-00935-6. PMC 9241296. PMID 35765081.

- ^ Anderson TR, Slotkin TA (August 1975). "Maturation of the adrenal medulla--IV. Effects of morphine". Biochemical Pharmacology. 24 (16): 1469–1474. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(75)90020-9. PMID 7.

- ^ Harauz G, Ishiyama N, Hill CM, Bates IR, Libich DS, Farès C (May 2004). "Myelin basic protein-diverse conformational states of an intrinsically unstructured protein and its roles in myelin assembly and multiple sclerosis". Micron. 35 (7): 503–542. doi:10.1016/s0968-4328(04)00096-4. PMID 15219899.

- ^ Moroi K, Sato T (August 1975). "Comparison between procaine and isocarboxazid metabolism in vitro by a liver microsomal amidase-esterase". Biochemical Pharmacology. 24 (16): 1517–1521. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(75)90029-5. PMID 8.

- ^ Marniemi J, Parkki MG (September 1975). "Radiochemical assay of glutathione S-epoxide transferase and its enhancement by phenobarbital in rat liver in vivo". Biochemical Pharmacology. 24 (17): 1569–1572. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(75)90080-5. PMID 9.

- ^ Bates IR, Feix JB, Boggs JM, Harauz G (February 2004). "An immunodominant epitope of myelin basic protein is an amphipathic alpha-helix". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (7): 5757–5764. doi:10.1074/jbc.m311504200. PMID 14630913.

- ^ a b Boggs JM (September 2006). "Myelin basic protein: a multifunctional protein". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 63 (17): 1945–1961. doi:10.1007/s00018-006-6094-7. PMC 11136439. PMID 16794783. S2CID 1076002.

- ^ Zand R, Li MX, Jin X, Lubman D (February 1998). "Determination of the sites of posttranslational modifications in the charge isomers of bovine myelin basic protein by capillary electrophoresis-mass spectroscopy". Biochemistry. 37 (8): 2441–2449. doi:10.1021/bi972347t. PMID 9485392.

- ^ Berger T, Rubner P, Schautzer F, Egg R, Ulmer H, Mayringer I, et al. (July 2003). "Antimyelin antibodies as a predictor of clinically definite multiple sclerosis after a first demyelinating event". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022328. PMID 12853586.

- ^ Pfister HW, Einhäupl KM, Wick M, Fateh-Moghadam A, Huber M, Schielke E, et al. (July 1989). "Myelin basic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients infected with HIV". Journal of Neurology. 236 (5): 288–291. doi:10.1007/bf00314458. PMID 2474637. S2CID 12178626.

- ^ Tejada-Simon MV, Zang YC, Hong J, Rivera VM, Zhang JZ (February 2003). "Cross-reactivity with myelin basic protein and human herpesvirus-6 in multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 53 (2): 189–197. doi:10.1002/ana.10425. PMID 12557285. S2CID 43317994.

- ^ Namer IJ, Steibel J, Poulet P, Armspach JP, Mohr M, Mauss Y, Chambron J (February 1993). "Blood-brain barrier breakdown in MBP-specific T cell induced experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. A quantitative in vivo MRI study". Brain. 116 ( Pt 1) (1): 147–159. doi:10.1093/brain/116.1.147. PMID 7680933.

- ^ Roy A, Hooper DC (August 2007). "Lethal silver-haired bat rabies virus infection can be prevented by opening the blood-brain barrier". Journal of Virology. 81 (15): 7993–7998. doi:10.1128/JVI.00710-07. PMC 1951307. PMID 17507463.

- ^ Wood DD, Vella GJ, Moscarello MA (October 1984). "Interaction between human myelin basic protein and lipophilin". Neurochemical Research. 9 (10): 1523–1531. doi:10.1007/BF00964678. PMID 6083474. S2CID 9751765.

- ^ Edwards AM, Ross NW, Ulmer JB, Braun PE (January 1989). "Interaction of myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 22 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1002/jnr.490220113. PMID 2467009. S2CID 33666906.

- ^ Harauz G, Ishiyama N, Hill CM, Bates IR, Libich DS, Farès C (2004). "Myelin basic protein-diverse conformational states of an intrinsically unstructured protein and its roles in myelin assembly and multiple sclerosis". Micron. 35 (7): 503–542. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2004.04.005. PMID 15219899.

Further reading

edit- Boylan KB, Ayres TM, Popko B, Takahashi N, Hood LE, Prusiner SB (January 1990). "Repetitive DNA (TGGA)n 5' to the human myelin basic protein gene: a new form of oligonucleotide repetitive sequence showing length polymorphism". Genomics. 6 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(90)90443-X. PMID 1689270.

- Kishimoto A, Nishiyama K, Nakanishi H, Uratsuji Y, Nomura H, Takeyama Y, Nishizuka Y (October 1985). "Studies on the phosphorylation of myelin basic protein by protein kinase C and adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (23): 12492–12499. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)38898-1. PMID 2413024.

- Saxe DF, Takahashi N, Hood L, Simon MI (1985). "Localization of the human myelin basic protein gene (MBP) to region 18q22----qter by in situ hybridization". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 39 (4): 246–249. doi:10.1159/000132152. PMID 2414074.

- Kamholz J, de Ferra F, Puckett C, Lazzarini R (July 1986). "Identification of three forms of human myelin basic protein by cDNA cloning". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (13): 4962–4966. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.4962K. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.13.4962. PMC 323864. PMID 2425357.

- Scoble HA, Whitaker JN, Biemann K (August 1986). "Analysis of the primary sequence of human myelin basic protein peptides 1-44 and 90-170 by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry". Journal of Neurochemistry. 47 (2): 614–616. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb04544.x. PMID 2426402. S2CID 22531833.

- Roth HJ, Kronquist K, Pretorius PJ, Crandall BF, Campagnoni AT (1986). "Isolation and characterization of a cDNA coding for a novel human 17.3K myelin basic protein (MBP) variant". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 16 (1): 227–238. doi:10.1002/jnr.490160120. PMID 2427738. S2CID 38277667.

- Popko B, Puckett C, Lai E, Shine HD, Readhead C, Takahashi N, et al. (February 1987). "Myelin deficient mice: expression of myelin basic protein and generation of mice with varying levels of myelin". Cell. 48 (4): 713–721. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90249-2. PMID 2434243. S2CID 25224473.

- Kamholz J, Spielman R, Gogolin K, Modi W, O'Brien S, Lazzarini R (April 1987). "The human myelin-basic-protein gene: chromosomal localization and RFLP analysis". American Journal of Human Genetics. 40 (4): 365–373. PMC 1684086. PMID 2437795.

- Roth HJ, Kronquist KE, Kerlero de Rosbo N, Crandall BF, Campagnoni AT (1987). "Evidence for the expression of four myelin basic protein variants in the developing human spinal cord through cDNA cloning". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 17 (4): 321–328. doi:10.1002/jnr.490170402. PMID 2442403. S2CID 37138877.

- Shoji S, Ohnishi J, Funakoshi T, Fukunaga K, Miyamoto E, Ueki H, Kubota Y (November 1987). "Phosphorylation sites of bovine brain myelin basic protein phosphorylated with Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase from rat brain". Journal of Biochemistry. 102 (5): 1113–1120. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122149. PMID 2449425.

- Wood DD, Moscarello MA (March 1989). "The isolation, characterization, and lipid-aggregating properties of a citrulline containing myelin basic protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (9): 5121–5127. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83707-3. PMID 2466844.

- Edwards AM, Ross NW, Ulmer JB, Braun PE (January 1989). "Interaction of myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 22 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1002/jnr.490220113. PMID 2467009. S2CID 33666906.

- Streicher R, Stoffel W (May 1989). "The organization of the human myelin basic protein gene. Comparison with the mouse gene". Biological Chemistry Hoppe-Seyler. 370 (5): 503–510. doi:10.1515/bchm3.1989.370.1.503. PMID 2472816.

- Lennon VA, Wilks AV, Carnegie PR (November 1970). "Immunologic properties of the main encephalitogenic peptide from the basic protein of human myelin". Journal of Immunology. 105 (5): 1223–1230. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.105.5.1223. PMID 4099924. S2CID 26451118.

- Carnegie PR (June 1971). "Amino acid sequence of the encephalitogenic basic protein from human myelin". The Biochemical Journal. 123 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1042/bj1230057. PMC 1176899. PMID 4108501.

- Baldwin GS, Carnegie PR (February 1971). "Specific enzymic methylation of an arginine in the experimental allergic encephalomyelitis protein from human myelin". Science. 171 (3971): 579–581. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..579B. doi:10.1126/science.171.3971.579. PMID 4924231. S2CID 36959912.

- Baldwin GS, Carnegie PR (June 1971). "Isolation and partial characterization of methylated arginines from the encephalitogenic basic protein of myelin". The Biochemical Journal. 123 (1): 69–74. doi:10.1042/bj1230069. PMC 1176900. PMID 5128665.

- Wood DD, Vella GJ, Moscarello MA (October 1984). "Interaction between human myelin basic protein and lipophilin". Neurochemical Research. 9 (10): 1523–1531. doi:10.1007/BF00964678. PMID 6083474. S2CID 9751765.

- Gibson BW, Gilliom RD, Whitaker JN, Biemann K (April 1984). "Amino acid sequence of human myelin basic protein peptide 45-89 as determined by mass spectrometry". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 259 (8): 5028–5031. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)42950-4. PMID 6201481.

- Pribyl TM, Campagnoni CW, Kampf K, Kashima T, Handley VW, McMahon J, Campagnoni AT (November 1993). "The human myelin basic protein gene is included within a 179-kilobase transcription unit: expression in the immune and central nervous systems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (22): 10695–10699. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9010695P. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.22.10695. PMC 47844. PMID 7504278.

- Shanshiashvili L, Mikeladze D (2003). "Some aspects of myelin basic protein". J. Biol. Phys. Chem. 3 (3): 96–9. doi:10.4024/18SH03R.jbpc.03.03.

External links

edit- Media related to Myelin basic proteins at Wikimedia Commons

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02686 (Myelin basic protein) at the PDBe-KB.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.