Madeleine L'Engle (/ˈlɛŋɡəl/; November 29, 1918[1] – September 6, 2007)[2] was an American writer of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and young adult fiction, including A Wrinkle in Time and its sequels: A Wind in the Door, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, Many Waters, and An Acceptable Time. Her works reflect both her Christian faith and her strong interest in modern science.

Madeleine L'Engle | |

|---|---|

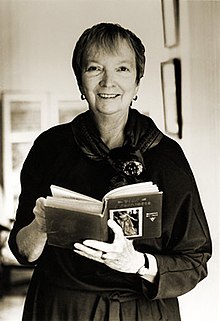

L'Engle in the 1980s | |

| Born | Madeleine L'Engle Camp November 29, 1918 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | September 6, 2007 (aged 88) Litchfield, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | Smith College |

| Period | 1945–2007 |

| Genre | |

| Notable works | A Wrinkle in Time and sequels |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

Early life

editMadeleine L'Engle Camp was born in New York City on November 29, 1918, and named after her great-grandmother, Madeleine Margaret L'Engle, otherwise known as Mado.[3] Her maternal grandfather was Florida banker Bion Barnett, co-founder of Barnett Bank in Jacksonville, Florida. Her mother, a pianist, was also named Madeleine: Madeleine Hall Barnett. Her father, Charles Wadsworth Camp, was a writer, critic, and foreign correspondent who, according to his daughter, suffered lung damage from mustard gas during World War I.[a]

L'Engle wrote her first story aged five and began keeping a journal aged eight.[5] These early literary attempts did not translate into academic success at the New York City private school where she was enrolled. A shy, awkward child, she was branded as stupid by some of her teachers. Unable to please them, she retreated into her own world of books and writing. Her parents often disagreed about how to raise her, and as a result she attended a number of boarding schools and had many governesses.[6][page needed]

The Camps traveled frequently. At one point, the family moved to a château near Chamonix in the French Alps, in what Madeleine described as the hope that the cleaner air would be easier on her father's lungs. Madeleine was sent to a boarding school in Switzerland. In 1933, L'Engle's grandmother fell ill, and they moved near Jacksonville, Florida to be close to her. L'Engle attended another boarding school, Ashley Hall, in Charleston, South Carolina. When her father died in October 1936, Madeleine arrived home too late to say goodbye.[7]

Education, marriage, and family

editL'Engle attended Smith College from 1937 to 1941. After graduating cum laude from Smith,[8] she moved to an apartment in New York City. L'Engle published her novels The Small Rain and Ilsa prior to 1942.[9] She met actor Hugh Franklin that year when she appeared in the play The Cherry Orchard by Anton Chekhov,[10] and she married him on January 26, 1946. Later she wrote of their meeting and marriage, "We met in The Cherry Orchard and were married in The Joyous Season."[8] The couple's first daughter, Josephine, was born in 1947.

The family moved to a 200-year-old farmhouse called Crosswicks in the small town of Goshen, Connecticut in 1952. To replace Franklin's lost acting income, they purchased and operated a small general store, while L'Engle continued with her writing. Their son Bion was born that same year.[11] Four years later, seven-year-old Maria, the daughter of family friends who had died, came to live with the Franklins and they adopted her shortly thereafter. During this period, L'Engle also served as choir director of the local Congregational church.[12]

Writing career

editL'Engle determined to give up writing on her 40th birthday (November 1958) when she received yet another rejection notice. "With all the hours I spent writing, I was still not pulling my own weight financially." Soon she discovered both that she could not give it up and that she had continued to work on fiction subconsciously.[13]

The family returned to New York City in 1959 so that Hugh could resume his acting career. The move was immediately preceded by a ten-week cross-country camping trip, during which L'Engle first had the idea for her most famous novel, A Wrinkle in Time, which she completed by 1960. It was rejected more than thirty times before she handed it to John C. Farrar;[13] it was finally published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1962.[12]

In 1960 the Franklins moved to an apartment on the Upper West Side, in the Cleburne Building on West End Avenue.[14] From 1960 to 1966 (and again in 1986, 1989 and 1990), L'Engle taught at St. Hilda's & St. Hugh's School in New York. In 1965 she became a volunteer librarian at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, also in New York. She later served for many years as writer-in-residence at the cathedral, generally spending her winters in New York and her summers at Crosswicks.[citation needed]

During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, L'Engle wrote dozens of books for children and adults. Four of the books for adults formed the Crosswicks Journals series of autobiographical memoirs. Of these, The Summer of the Great-grandmother (1974) discusses L'Engle's personal experience caring for her aged mother, and Two-Part Invention (1988) is a memoir of her marriage, completed after her husband's death from cancer on September 26, 1986.

On writing for children

editSoon after winning the Newbery Medal for her 1962 "junior novel" A Wrinkle in Time, L'Engle discussed children's books in The New York Times Book Review.[15] The writer of a good children's book, she observed, may need to return to the "intuitive understanding of his own childhood," being childlike although not childish. She claimed, "It's often possible to make demands of a child that couldn't be made of an adult... A child will often understand scientific concepts that would baffle an adult. This is because he can understand with a leap of the imagination that is denied the grown-up who has acquired the little knowledge that is a dangerous thing." Of philosophy, etc., as well as science, "the child will come to it with an open mind, whereas many adults come closed to an open book. This is one reason so many writers turn to fantasy (which children claim as their own) when they have something important and difficult to say."[15]

Religious beliefs

editL'Engle was a Christian who attended Episcopal churches and believed in universal salvation, writing that "All will be redeemed in God's fullness of time, all, not just the small portion of the population who have been given the grace to know and accept Christ. All the strayed and stolen sheep. All the little lost ones."[16] As a result of her promotion of Christian universalism, many Christian bookstores refused to carry her books, which were also frequently banned from evangelical Christian schools and libraries. At the same time, some of her most secular critics attacked her work for being far too religious.[17]

Her views on divine punishment were similar to those of George MacDonald, who also had a large influence on her fictional work. She said "I cannot believe that God wants punishment to go on interminably any more than does a loving parent. The entire purpose of loving punishment is to teach, and it lasts only as long as is needed for the lesson. And the lesson is always love."[18]

In 1982, L'Engle reflected on how suffering had taught her. She told how suffering a "lonely solitude" as a child taught her about the "world of the imagination" that enabled her to write for children. Later she suffered a "decade of failure" after her first books were published. It was a "bitter" experience, yet she wrote that she had "learned a lot of valuable lessons" that enabled her to persevere as a writer.[19]

Later years, death, and legacy

editL'Engle was seriously injured in an automobile accident in 1991, but recovered well enough to visit Antarctica in 1992.[12] Her son, Bion Franklin, died on December 17, 1999, from the effects of prolonged alcoholism.[20] He was 47 years old.[21]

In her final years, L'Engle became unable to teach or travel due to reduced mobility from osteoporosis, especially after suffering an intracerebral hemorrhage in 2002. She also abandoned her former schedule of speaking engagements and seminars. A few compilations of older work, some of it previously unpublished, appeared after 2001.

L'Engle died of natural causes at Rose Haven, a nursing facility close to her home in Litchfield, Connecticut, on September 6, 2007, according to a statement made by her publicist the following day.[22] She is interred in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan.[23]

In 2018, her granddaughters Charlotte Jones Voiklis and Léna Roy published Becoming Madeleine: A Biography of the Author of A Wrinkle in Time by Her Granddaughters.[24]

A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle by Sarah Arthur was also published in 2018.[25]

L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time was adapted into a film twice by Disney. A television film, directed by John Kent Harrison, premiered on May 10, 2004. When asked in an interview with Newsweek if the film "met her expectations", L'Engle said, "I have glimpsed it. ... I expected it to be bad, and it is."[26] A theatrical film, directed by Ava DuVernay, premiered March 9, 2018.[27]

In celebration of L'Engle's centenary year, Writing for Your Life hosted the inaugural Madeleine L'Engle Conference: Walking on Water on November 16, 2019, in New York City, New York, at All Angels' Church on the Upper West Side. Katherine Paterson served as the keynote speaker.[28]

Awards, honors, and organizations

editIn addition to the numerous awards, medals, and prizes won by individual books L'Engle wrote, she personally received many honors over the years.[12] These included being named an Associate Dame of Justice in the Venerable Order of Saint John (1972);[29] the USM Medallion from The University of Southern Mississippi (1978); the Smith College Medal "for service to community or college which exemplifies the purposes of liberal arts education" (1981); the Sophia Award for distinction in her field (1984); the Regina Medal (1985); the ALAN Award for outstanding contribution to adolescent literature, presented by the National Council of Teachers of English (1987);[30] and the Kerlan Award (1991).

In 1985 she was a guest speaker at the Library of Congress, giving a speech entitled "Dare to be Creative!" That same year she began a two-year term as president of the Authors Guild. In addition she received over a dozen honorary degrees from as many colleges and universities, such as Haverford College.[31] Many of these name her as a Doctor of Humane Letters, but she was also made a Doctor of Literature and a Doctor of Sacred Theology, the latter at Berkeley Divinity School in 1984. In 1995 she was writer-in-residence for Victoria Magazine. In 1997 she was recognized for Lifetime Achievement from the World Fantasy Awards.[32]

L'Engle received the annual Margaret A. Edwards Award from the American Library Association in 1998. The Edwards Award recognizes one writer and a particular body of work for a "significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature." Four books by L'Engle were cited: Meet the Austins, A Wrinkle In Time, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, and A Ring of Endless Light (published 1960 to 1980).[33] In 2004 she received the National Humanities Medal[13] but could not attend the ceremony due to poor health.

L'Engle was inducted into the New York Writers Hall of Fame in 2011.[34]

In a 2012 survey of School Library Journal readers, A Wrinkle in Time was voted the best children's novel after Charlotte's Web.[35][36]

In 2013, a crater on Mercury was named after L'Engle.[37]

At Smith College, a fellowship is available in L'Engle's name to visit and use the special collections available there. This fund provides stipends to support travel by researchers—from novices to advanced, award-winning scholars—to explore the resources available in the Smith College Archives, Mortimer Rare Book Collection, and Sophia Smith Collection of Women's History.[38]

The Madeleine L'Engle Collection

editSince 1976, Wheaton College in Illinois has maintained a special collection of L'Engle's papers, and a variety of other materials, dating back to 1919.[39] The Madeleine L'Engle Collection includes manuscripts for the majority of her published and unpublished works, as well as interviews, photographs, audio and video presentations, and an extensive array of correspondence with both adults and children, including artwork sent to her by children.

In 2019, a collection of 43 linear feet of L'Engle's family, personal, and literary papers came to the Sophia Smith Collection of Women's History at Smith College. They had been donated by her literary estate.[40]

Bibliographic overview

editMost of L'Engle's novels from A Wrinkle in Time onward are centered on a cast of recurring characters, who sometimes reappear decades older than when they were first introduced. The "Kairos" books are about the Murry and O'Keefe families, with Meg Murry and Calvin O'Keefe marrying and producing the next generation's protagonist, Polyhymnia O'Keefe. L'Engle wrote about both generations concurrently, with Polly (originally spelled Poly) first appearing in 1965, well before the second book about her parents as teenagers (A Wind in the Door, 1973). The "Chronos" books center on Vicky Austin and her siblings. Although Vicky's appearances all occur during her childhood and teenage years, her sister Suzy also appears as an adult in A Severed Wasp, with a husband and teenage children. In addition, two of L'Engle's early protagonists, Katherine Forrester and Camilla Dickinson, reappear as elderly women in later novels. Rounding out the cast are several characters "who cross and connect": Canon Tallis, Adam Eddington, and Zachary Gray, who each appear in both the Kairos and Chronos books.[41]

In addition to novels and poetry, L'Engle wrote many nonfiction works, including the autobiographical Crosswicks Journals and other explorations of the subjects of faith and art. For L'Engle, who wrote repeatedly about "story as truth", the distinction between fiction and memoir was sometimes blurred. Real events from her life and family history made their way into some of her novels, while fictional elements, such as assumed names for people and places, can be found in her published journals.[42]

Works

editNovels for young adults

editChronos & Kairos series:

- Chronos (The Austin Family Chronicles):

- Meet the Austins (1960) ISBN 0-374-34929-0

- The Moon by Night (1963) ISBN 0-374-35049-3

- 2.5. The Twenty-four Days Before Christmas (1984) ISBN 0-87788-843-4)[b]

- The Young Unicorns (1968) ISBN 0-374-38778-8

- A Ring of Endless Light (1980) ISBN 0-374-36299-8 (Newbery Honor Book)

- 4.5. The Anti-Muffins (1980) ISBN 0-8298-0415-3

- Troubling a Star (1994) ISBN 0-374-37783-9

- 5.5. Miracle on 10th Street: And Other Christmas Writings (1998), a short story collection including The Twenty-four Days Before Christmas (1984) and A Full House: An Austin Family Christmas (1999)

- 5.6. A Full House: An Austin Family Christmas (1999) ISBN 0-87788-020-4)[b]

- 5.7. "Rob Austin and the Millennium Bug", a short story included in the anthology Second Sight: Stories for a New Millennium (1999)

- Kairos (The Murry-O'Keefe Family Chronicles):

Note: Within the Kairos series, books 1-4 of the first generation plus An Acceptable Time are jointly titled the Time Quintet.- First-generation (Murry series):

- A Wrinkle in Time (1962; Newbery Award Winner) ISBN 0-374-38613-7

- A Wind in the Door (1973) ISBN 0-374-38443-6

- 2.5. Intergalactic P.S. 3 (1970) ISBN 0-525-63405-3

- A Swiftly Tilting Planet (1978) ISBN 0-374-37362-0 —National Book Award in category Children's Books (paperback).[43][c]

- Many Waters (1986) ISBN 0-374-34796-4

- Second-generation (O'Keefe Family series):

- The Arm of the Starfish (1965) ISBN 0-374-30396-7

- Dragons in the Waters (1976) ISBN 0-374-31868-9

- A House Like a Lotus (1984) ISBN 0-374-33385-8

- An Acceptable Time (1989) ISBN 0-374-30027-5

- First-generation (Murry series):

Stand-alone releases:

- And Both Were Young (1949), revised and reissued with new material (1983) ISBN 0-440-90229-0

- The Journey with Jonah (1967) ISBN 0-374-33927-9

- The Joys of Love (2008) ISBN 0-374-33870-1[44]

Novels

editKatherine Forrester Vigneras series:

- The Small Rain (1945) ISBN 0-374-26637-9

- Prelude (1968), no ISBN, an adaptation of the first half of The Small Rain

- A Severed Wasp (1982) ISBN 0-374-26131-8

Camilla Dickinson series:

- Camilla Dickinson (1951), later republished in slightly different form as Camilla (1965), novel of young adult ISBN 0-440-01020-9

- A Live Coal in the Sea (1996) ISBN 0-374-18989-7

Stand-alones:

- Ilsa (1946) ISBN 9-781504-049443

- A Winter's Love (1957), ISBN 0-345-30644-9

- The Love Letters (1966), revised and reissued as Love Letters (2000) ISBN 0-87788-528-1

- The Other Side of the Sun (1971) ISBN 0-87788-615-6[45]

- Certain Women (1992) ISBN 0-374-12025-0

Note: some ISBNs given are for later paperback editions, since no such numbering existed when L'Engle's earlier titles were published in hardcover.

Children's books

editPicture books:

- Dance in the Desert (1969) ISBN 0-374-41684-2

- The Glorious Impossible (1990) ISBN 0-671-68690-9

- The Other Dog (2001) ISBN 1-58717-040-X

- A Book, Too, Can Be a Star (2022), a picture book biography of Madeleine L'Engle

Short stories

editCollections:

- The Sphinx at Dawn: Two Stories (1982), collection of 2 short stories:

- "Pakko's Camel", "The Sphinx at Dawn"

- 101st Miracle: Early Short Stories by Madeleine L'Engle (1999), collection of 12 short stories: ISBN 1-88091-343-7

- "Poor Little Saturday", "Six Good People", and more. (Although there is an ISBN listed, there is no record of this title ever being published.)

- The Moment of Tenderness (2020), collection of 18 short stories

Poems

editCollections:

- The Weather of the Heart: Selected Poems (1978)

- Wintersong: Christmas Readings (1996, with Luci Shaw) ISBN 1-57383-332-0

- Mothers And Daughters (1997) ISBN 1-89683-605-4

- The Ordering of Love: The New and Collected Poems of Madeleine L'Engle (2005), collection of nearly 200 poems, including 18 that have never before been published: ISBN 0-87788-086-7

- "Lines Scribbled on an Envelope", "The Weather of the Heart", "A Cry Like a Bell", and more

Plays

edit- 18 Washington Square South: A Comedy In One Act (1944)

Non-fiction

edit- Autobiographies and memoirs

Crosswicks Journals series:

- A Circle of Quiet (1972) ISBN 0-374-12374-8

- The Summer of the Great-grandmother (1974) ISBN 0-374-27174-7

- The Irrational Season (1977) ISBN 0-374-17733-3

- Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage (1988) ISBN 0-374-28020-7 (U.K. and Australia title: From This Day Forward)

Stand-alones:

- Glimpses of Grace: Daily Thoughts and Reflections (1996, with Carole F. Chase) ISBN 0-06065-281-0

- Friends for the Journey (1997, with Luci Shaw) ISBN 0-89283-986-4

- My Own Small Place: Developing the Writing Life (1998) ISBN 0-87788-571-0 (Although there is a ISBN for this title, there is no record of it having ever been released.)

- L'Engle, Madeleine (2001). Carole F. Chase (ed.). Madeleine L'Engle Herself: Reflections on a Writing Life. ISBN 0-87788-157-X.

- Religion

Genesis Trilogy:

- And It Was Good: Reflections on Beginnings (1983) ISBN 0-87788-046-8

- A Stone for a Pillow (1986) ISBN 0-87788-789-6

- Sold into Egypt (1989) ISBN 0-87788-766-7

Stand-alones:

- Everyday Prayers (1974) ISBN 0-81921-154-0

- Prayers for Sunday (1975) ISBN 0-81921-153-2

- Spirit And Light: Essays In Historical Theology (1976) ISBN 0-81640-310-4

- Ladder of Angels: Stories from the Bible Illustrated by Children of the World (1979) ISBN 0-06255-619-3

- Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (1980) ISBN 0-87788-918-X

- Trailing Clouds of Glory: Spiritual Values in Children's Literature (1985) ISBN 0-66432-721-4

- The Rock that is Higher: Story as Truth (1993)

- Anytime Prayers (1994) ISBN 0-87788-055-7

- Penguins and Golden Calves: Icons and Idols in Antarctica and Other Spiritual Places (1996) ISBN 0-87788-631-8

- Bright Evening Star: Mystery of the Incarnation (1997) ISBN 0-87788-079-4

- Miracle on 10th Street: And Other Christmas Writings (1998) ISBN 0-87788-531-1

- Includes two short stories about the Austin Family Chronicles series.

- A Prayerbook for Spiritual Friends (1999, with Luci Shaw) ISBN 0-80663-892-3

- Mothers and Sons (2000) ISBN 0-87788-567-2

- Writing

- Dare To Be Creative!: A Lecture Presented At The Library Of Congress, November 16, 1983 (1984) ISBN 0-84440-456-X

- Do I Dare Disturb the Universe?: The Celebrated Speech (2012)

Adaptations

edit- A Ring of Endless Light (2002), telefilm directed by Greg Beeman, based on young adult novel A Ring of Endless Light

- A Wrinkle in Time (2003), telefilm directed by John Kent Harrison, based on young adult novel A Wrinkle in Time

- Camilla Dickinson (2012), film directed by Cornelia Duryée, based on young adult novel Camilla Dickinson

- A Wrinkle in Time (2018), film directed by Ava DuVernay, based on young adult novel A Wrinkle in Time

Notes

edit- ^ In a 2004 New Yorker profile of the writer, relatives of L'Engle disputed the mustard gas story, stating instead that Camp's illness was caused by alcoholism.[4]

- ^ a b The two Christmas books are shorter works, heavily illustrated but not actually picture books. The events in each of these stories take place prior to the events of Meet the Austins.

- ^ A Swiftly Tilting Planet won the award for paperback Children's Literature. From 1980 to 1983 in National Book Award history, there were dual awards for hardcover and paperback books in many categories. Most of the paperback award-winners were reprints, including this one.

References

edit- ^ "UPI Almanac for Friday, Nov. 29, 2019". United Press International November 29, 2019. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

…author Madeleine L'Engle in 1918

- ^ Martin, Douglas (September 8, 2007). "Madeleine L'Engle, Children's Writer, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (1974). The Summer of the Great-Grandmother. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 164. ISBN 0-374-27174-7.

- ^ Zarin, Cynthia (April 12, 2004). "The Storyteller". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Chase, Carole F. (1972). Suncatcher: A Study of Madeleine L'Engle And Her Writing. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 30–31. ISBN 1-880913-31-3.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (1972). A Circle of Quiet. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-374-12374-8.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (1974). The Summer of the Great-Grandmother. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux. p. 119. ISBN 0-374-27174-7.

- ^ a b Franklin, Hugh (August 1963). "Madeleine L'Engle". Horn Book Magazine. Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "Learn About Madeleine L'Engle, Beloved Author of A Wrinkle in Time". Madeleine L'Engle. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Madeleine L'Engle at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Chase, Carole F. (1972). Suncatcher: A Study of Madeleine L'Engle And Her Writing. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 72. ISBN 1-880913-31-3.

- ^ a b c d Chase, Carole F. (1972). "A Chronology of Madeleine L'Engle's Life and Books". Suncatcher: A Study of Madeleine L'Engle And Her Writing. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 169–73. ISBN 1-880913-31-3.

- ^ a b c "Madeleine L'Engle". Awards & Honors: 2004 National Humanities Medalist. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ Ohrstrom, Lysandra (March 7, 2008). "West End Home of A Wrinkle in Time Author Sells for $4 M". Observer. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009.

- ^ a b L'Engle, Madeleine (May 12, 1963). "How's One to Tell?". The New York Times. p. BR21.

- ^ Wilson, John (September 1, 2003). "A Distorted Predestination". Christianity today.

- ^ Eccleshare, Julia (October 2, 2007). "Madeleine L'Engle: Bestselling children's author, renowned for A Wrinkle in Time". The Guardian.

- ^ Morgan, Christopher W; Peterson, Robert A. Hell Under Fire: Modern Scholarship Reinvents Eternal Punishment. p. 171.

- ^ Madeleine L'Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art (New York: Bantam Books, 1982), 58.

- ^ Zarin, Cynthia (April 12, 2004). "The storyteller: fact, fiction, and the books of Madeleine L'Engle". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ "Madeleine L'Engle". Religion & Ethics News Weekly. PBS. November 17, 2000.

- ^ "Esther Mitgang; Madeleine L'Engle". Publishers Weekly (obituaries). June 21, 2007. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ "Madeleine L'Engle, writer and Episcopalian, dies at 88". EpiscopalChurch.org. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ "Becoming Madeleine Book Launch Information". Madeleine L'Engle. January 19, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Jeffrey (May 23, 2019). "The spirit of Madeleine L'Engle". Christian Century. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Madeleine L'Engle". Newsweek. May 6, 2004.

- ^ "Why A Wrinkle in Time Will Change Hollywood". Time. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "The 2019 Madeleine L'Engle Conference — Walking on Water". Writing for Your Life. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "No. 47369". The London Gazette. November 4, 1977. p. 13902.

- ^ "One Great Read Programs and Events A Wrinkle in Time by Madeline L'Engle". www.tcpl.lib.in.us. Tippecanoe County Public Library. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "A Commencement for the Millennium". Haverford News. Haverford College. 2002. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ "Award Winners and Nominees". World Fantasy Convention. 2010. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "1998 Margaret A. Edwards Award Winner". Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA); American Library Association (ALA). 1998. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ "Hall of Fame". Empire State Center for the Book. May 1, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (June 28, 2012). "Top 100 Children's Novels #2: A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle". A Fuse 8 Production. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "SLJ's Top 100 Children's Novels" (PDF). School Library Journal (poster presentation of reader poll results). Fuse #8. August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "L'Engle". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. NASA. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Smith College Libraries. "Madeleine L'Engle Travel Research Fellowships". Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ "About the Collection – Madeleine L'Engle". Wheaton. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007.

- ^ Smith College Special Collections. "Collection: Madeleine L'Engle papers | Smith College Finding Aids". Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ L'Engle, Madeleine (1986). The L'Engle Family Tree, in Many Waters. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-374-34796-4.

- ^ Chase, Carole F. (1972). Suncatcher: A Study of Madeleine L'Engle And Her Writing. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 89–90. ISBN 1-880913-31-3.

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1980". National Book Foundation. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ "The Joys of Love". Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ l'Engle, Madeleine (1996). The other side of the Sun. Harold Shaw Publishers. ISBN 0-87788-615-6.

Further reading

edit- Hein, Rolland (2002). Christian Mythmakers: C. S. Lewis, Madeleine L'Engle, J. R. R. Tolkien, George MacDonald, G. K. Chesterton and Others. Cornerstone Press Chicago. ISBN 0-940895-48-X.

- Soares, Manuela (2003). A Reading Guide to A Wrinkle in Time. Scholastic BookFiles. ISBN 0-439-46364-5.

External links

edit- Official website

- Madeleine L'Engle at IMDb

- Madeleine L'Engle at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Madeleine L'Engle at Library of Congress, with 32 library catalog records

- "Madeleine L'Engle | Authors | Macmillan". Macmillan US.

- "Obituary". The Times. September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009.

- "I Dare You". Newsweek (interview). May 6, 2004.

- "Madeleine L'Engle – WaterBrook & Multnomah". Random House. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- "Madeleine L'Engle | February 10, 2012 | Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly | PBS" (interview). PBS. November 17, 2000. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- "Fantasy and Faith". First Things. November 2007.

- "Madeleine L'Engle Papers, 1918–2006". Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections.

- Madeleine L'Engle papers at the Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

- Interview with Madeline L'Engle about her 1990 Kerlan Award, All About Kids! TV Series #47 (1990)