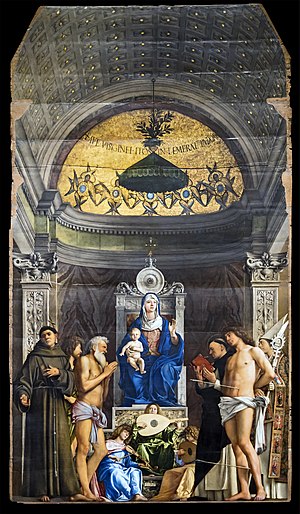

The San Giobbe Altarpiece (Italian: Pala di San Giobbe) is a c. 1487 altarpiece in oils on panel by the Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini. Inspired by a plague outbreak in 1485, this sacra conversazione painting is unique in that it was designed in situ with the surrounding architecture of the church (a first for Bellini), and was one of the largest sacra conversazione paintings at the time. Although it was originally located in the Church of San Giobbe, Venice, it is now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice after having been stolen by Napoleon Bonaparte.

| San Giobbe Altarpiece | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Giovanni Bellini |

| Year | c. 1487 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions | 471 cm × 258 cm (185 in × 102 in) |

| Location | Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice |

History

editCreation

editJust prior to 1478, Giovanni Bellini was commissioned to paint the altarpiece by an unknown individual from the Scuola di San Giobbe, to be placed opposite the Martini Chapel of the soon-to-be consecrated Church of San Giobbe. The friars and sisters of the San Giobbe Hospice had founded the Scuola di San Giobbe and replaced an old oratory dedicated to Job with a new church dedicated to both St. Job and St. Bernardino. This was strongly suggested by the confraternity's patron, the doge Cristoforo Moro.[1] This altarpiece marks the first time Bellini used the concept of creating an illusionary space to house a sacra conversazione that appears as though it is an extension of the church architecture itself, and honored St. Job with the position closest to the Christ child. The painting was designed in situ to incorporate the architecture of the Church of San Giobbe; the arches inside the painting match in perspective and design the marble arches of the church framing the painting.[1] Because the Church of San Giobbe did not have two chapels, only the Martini Chapel and an empty space opposite the chapel, the altarpiece was painted in order to create a space that would illusionistically balance the church with “two” chapels on either side. Hence the piece's size and detailed visual description of the perspective in fictive space was intended to serve as a second chapel, and the perspective, along with the similar framing within the painting and surrounding the painting, would give that proper illusion.[2]

The actual patron of the painting is unknown, although it is assumed that the patron was a member of the Scuola di San Giobbe. This assumption is currently being debated, as the size and detail of this painting would warrant a large monetary compensation to Giovanni Bellini, which would be difficult for such a small church. One hypothesis is that Cristoforo Moro, who also patronized the church and influenced the rededication of the church to both St. Job and St. Bernardino, had commissioned the painting.[2]

The piece, although having no textual proof of exact completion date, was recorded as being complete in the newly consecrated Church of San Giobbe by 1493. The Venetian scholar Marcus Antonio wrote about the piece in its completed form in his “De Venetae Urbis Situ” (A written guide to Venice), and Venetian historian Marin Sanudo had included a comment about the piece’s beauty in a list of Venice’s holy sites, both written in 1493, marking that year the very latest possible date of completion.[2]

Although Giovanni Bellini's cursive signature has come into question and had often been used by imitators, this piece is widely accepted to be Bellini's. His signature is on a plaque just below the feet of the middle musician angel and is in an italic form, "Ioannes Bellinus", which was seldom used by imitators.[3]

Provenance

editThe altarpiece remained in the church of San Giobbe until 1814–1818,[4] until Napoleon Bonaparte, during his ransacking of Venice, stole this piece, along with many others. Eventually it was returned to its city of origin, but was given to the Galleria dell'Accademia in Venice, where it is displayed with the other altarpieces from the Church of San Giobbe.[5]

Composition

editFigures

editFeatured in the center are the Madonna and Child, seated above several other religious figures. Below the central figures are three angels, each playing a musical instrument. The saints flanking the throne are each met with an opposite, both physically and historically. On the viewer’s far left (to the Madonna and Child’s right) is St. Francis, to the right of him is John the Baptist, and in the most notable position and titular figure of the altarpiece’s church, St. Job. Just right of the throne (to the Madonna and Child’s left) are St. Sebastian, St. Dominic and furthest to the right is Franciscan Bishop St. Louis of Toulouse.[1]

Job is bearded and wears only a loincloth, mirroring the youthful, long-haired, clean-shaven figure opposite him in St. Sebastian. St. Sebastian, also posed with only a loincloth, has two arrows in his body referencing his torture. However, he is not bloodied or in agony, but is quite clean and tranquil as he looks upon the Christ child. St. Dominic is posed with a religious text in his hands, and is clean-clothed, appearing to be a studious figure, even when placed in front of the Madonna and Child. As his opposite stands John the Baptist, an unkempt figure, not shaven, and staring at Christ. St. Louis shows the religious garb of his high position and represents the religiosity of the Church. St. Francis, who unlike the other characters, is not looking to the Christ child, but at the viewer, and is reaching out and welcoming the viewer into the scene.[6]

As a recourse for the Church of San Giobbe moving their old patron, Job, into a lower position, Bellini honored St. Job in this piece by placing him not only in the position closest to the Mother and Child, but also honored him by including references to the Cathedral of Saint Mark in Venice by way of the vaulted ceiling.[1]

Very few of Bellini’s works with the Madonna and Child include the full length of the saints flanking the throne. The San Giobbe Altarpiece shares this quality along with the Frari triptych, the Priuli triptych and the San Zaccaria Altarpiece.[2]

Setting

editAbove the Madonna and Child is a coffered vault ceiling, which is an architectural reference to the Saint Mark's Basilica. Bellini creates a fictive chapel within the Church of San Giobbe, while combining figures that were never meant to be together in one space. He also creates a fictive space in terms of architecture, with the plaster columns framing the piece and paralleling structures from the Saint Mark’s Cathedral. This technique of placing holy figures as such in a fictive space was new to Venetian art, a technique that will be commonly repeated by future Venetian artists.[1]

Common to the genre at the time, sacra conversazione paintings included some form of sky, or were placed within a structure that is somehow open to the outside world. Unlike all his other sacra conversazione paintings, the San Giobbe Altarpiece is unique in that it takes place in an interior space, due to the fact that it was meant to compensate for the Church of San Giobbe’s lack of a second chapel across from the Martini chapel.[2]

The upper part features a perspective coffered ceiling, flanked with pillars which are copies of the real ones at the original altar. Behind the Madonna is a dark niche. In the latter's half-dome is a gilt mosaic decoration in the Venetian style.

This altarpiece is an example of a pala altar, or a single-paneled altar, a technique first introduced to Venice by Bellini and heavily influenced by Antonello da Messina.[7][8]

Geometry

editTriangles during the Renaissance were an important symbol of the Divine. Many artists in the late 15th century included triangular compositions in their pieces. This linked triangles with the divine, and was often a kind of map for the Holy Trinity. The asymmetry in this piece creates a contrast with the figures on opposing sides, and the triangles can be found with these various groupings.[9]

The figures are also opposite in symmetry across the vertical center line. The older St. Job stands opposite the youthful St. Sebastian, the wild John the Baptist is across from the tame and studious St. Dominic, and the exuberant attire of St. Louis opposes St. Frances’ plain robes.[6]

Symbols

editSacra Conversazione

editThe altarpiece is a sacra conversazione, a piece of art that combines holy figures from across time into one place, surrounding the Virgin and Christ child, often with angels nearby playing music. One difference between Bellini’s sacra conversazione and others is that it appears as though the figures are interacting with each other. The angels are gazing up at St. Job, St. Job is looking at the Virgin, St. Francis on the left is breaking the fourth wall of the painting and inviting the audience into the fictive scene. When compared to other sacra conversazione, examples being the San Marco Altarpiece, the Frari Triptych and the San Zaccaria Altarpiece, not only is the San Giobbe Altarpiece much larger and shows the full stature of all figures in the scene, but it also is contained in an interior space, which was very uncommon in Venetian pieces at the time, which oft included an open sky, or an airy feel to the background.[2]

Holy Reference

editSeveral pieces in the painting point toward reinforcement of the Virgin Mother’s immaculate nature. Her hand in the position of the Annunciation and the Latin phrase above on the vaulted-ceiling reads “Ave Virginei Flos Intemerate Pudoris”, roughly translating to “Hail, undefiled flower of virgin modesty”.[10] St. Francis, inviting the viewer in, is also displaying his holiness by way of his Stigmata.[6]

The accuracy of the angel musicians at the feet of the Mother and Child is well-portrayed in proper string-instrument technique. One studies its right hand strumming the lute, the other two peering up at St. Job standing next to them, a link that has suggested ta link between St. Job and music. Even the lutes themselves are accurate in construction to lutes, matching the rose piece in the painting with those of real ornamentations at the time.[10]

Evocation of Saints

editThe plague of 1485 greatly influenced the painting by way of the inclusion of St. Sebastian and his opposite, St. Job. The arrow at St. Sebastian’s side symbolizes the plague, and his presence in the painting would be an invocation used in response to the plague that was hitting Venice at the time. St. Job symbolizes suffering through his plague-like illness, through which he relies on his faith to endure. Not only were both St. Sebastian and St. Job associated with suffering and pain, but the Scuola di San Giobbe was originally a hospice that was built in response to a plague, hence the representation of these saints and their faith to give hope to patients.[10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e Goffen, Rona (October 1985). "Bellini's Altarpieces, Inside and Out". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 5 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1086/sou.5.1.23202259. ISSN 0737-4453. S2CID 192969185.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoshi, Seiko (2008). ""A Quantitative Analysis of the Venetian Altarpieces -The Case of San Giobbe Altarpiece by Giovanni Bellini"". CARLS Series of Advanced Study of Logic and Sensibility. 1: 349–362 – via KOARA.

- ^ Pincus, Debra (2008). ""Giovanni Bellini's Humanist Signature: Pietro Bembo, Aldus Manutius and Humanism in Early Sixteenth-Century Venice"". Atribus et Historiae. 29 (58): 89–119. JSTOR 40343651 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Rugolo, Ruggero (2013). Venise – Où trouver Bellini, Carpaccio, Titen, Tintoret, Véronèse (in French). Scala. p. 12. ISBN 9788881173891.

- ^ Boulton, Susie (2010). Venice and the Veneto. United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Incorporated.

- ^ a b c Goffen, Rona (1986). ""Bellini, San Giobbe and Altar Egos"". Artibus et Historiae. 7 (14): 57–70. doi:10.2307/1483224. JSTOR 1483224 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Peter Humfrey et al, "Bellini Family," Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, Oxford university Press (2003), https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T007643

- ^ John T. Paoletti and Gary M. Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2012), 322–326.

- ^ Zorach, Rebecca (2011). "The Passionate Triangle". University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-98939-6.

- ^ a b c Richardson, Joan Olivia (1979). "Hodegetria and Ventia Virgo: Giovanni Bellini's San Giobbe Altarpiece". University of British Columbia.

External links

editSources

edit- Olivari, Mariolina (2007). "Giovanni Bellini". Pittori del Rinascimento. Florence: Scala.

- Nepi Sciré, Giovanna & Valcanover, Francesco, Accademia Galleries of Venice, Electa, Milan, 1985, ISBN 88-435-1930-1