The Malé Friday Mosque or the Malé Hukuru Miskiy (Dhivehi: މާލެ ހުކުރު މިސްކިތް) also known as the Old Friday Mosque is one of the oldest and most ornate mosques in the city of Malé, Kaafu Atoll, Maldives. Coral boulders of the genus Porites, found throughout the archipelago, are the basic materials used for construction of this and other mosques in the country because of its suitability. Although the coral is soft and easily cut to size when wet, it makes sturdy building blocks when dry.[1] The mosque was added to the tentative UNESCO World Heritage cultural list in 2008 as unique examples of sea-culture architecture.[1]

| Malé Friday Mosque | |

|---|---|

މާލެ ހުކުރު މިސްކިތް | |

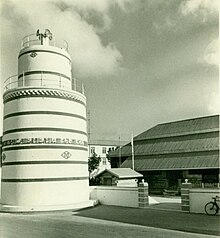

Male Friday Mosque minaret | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Rite | Sunni / Sufism |

| Location | |

| Location | Malé, Maldives |

| State | Kaafu Atoll |

| Territory | Malè |

| Geographic coordinates | 04°10′41″N 73°30′45″E / 4.17806°N 73.51250°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Traditional Maldivian architecture |

| Completed | 1658 |

Master carpenters of the Malé Hukuru Miskiy were Ali Maavadi Kaleyfaanu and Mahmud Maavadi Kaleyfaanu from Kondey, Huvadu.[2]

The calligrapher was Chief Justice Al Faqh Al Qazi Jamaaludheen.[2]

It took 2 years to construct the mosque. In terms of artistic excellence and construction technique using only interlocking assembly, it is one of the finest coral stone buildings of the world.[2]

Location

editThe mosque is opposite to the Medhu Ziyaaraiy and the Muliaage in the capital Malé. The Medhu Ziyaaraiy is the tomb of a Sunni Muslim visitor named Abu al-Barakat Yusuf al-Barbari who introduced Islam to the Maldives in 1153 AD. Malé Friday Mosque was built in 1656, this is the oldest mosque in Maldives.

History

editThe mosque was built in 1648, during the reign of Ibrahim Iskandar I (1648–1687). It was built over an earlier mosque constructed in 1153 by the first Muslim Sultan of Maldives, Dhovemi, after his conversion to Islam. Although the older mosque was reportedly refurbished by Ahmed Shihabuddeen in 1338, there are no written records attesting this.[3][1] In 1656, Iskandar began building a new mosque when the old one became too small to accommodate the increasing number of devotees. Its construction, which took one-and-a-half years, was completed in 1658. Built primarily of coral, the mosque originally had a thatched roof (common during the period).[1] After his 1668 Hajj, Ibrahim I began building a munnaaru (minaret) and a gate at the southern end of the mosque. The minaret, patterned on those at the entrance to Mecca, is surrounded by a 17th-century cemetery with intricately-carved tombstones and mausoleums.[1][3]

In 1904, Muhammad Shamsuddeen III (1902–1934) replaced the thatched roof and southern gateway with corrugated-iron sheeting. Further renovations were made in 1963, converting the roof supports to teak wood and replacing the corrugated-iron sheeting with aluminium. In 1987 and 1988, an Indian team from the National Research Laboratory for Conservation of Cultural Property and the National Centre for Linguistic and Historical Research in Malé did conservation work on the mosque.[1]

The mosque has been in continuous use since it was built.[1] The mosque was reportedly built over an ancient temple which predated Islam; the original temple faced the setting sun, rather than Mecca.[4]

-

Sultans' Tombs, Malé Friday Mosque

-

Woodcarving inside Male' Friday Mosque

Features

editThe Malé Friday Mosque is oriented west. Its prayer carpet is angled towards the mosque's northwest corner, so worshippers can face Mecca while they pray.[4] Devotees enter the mosque from either of the two entrance gates that lead to the mosque's dhaala.

It has intricate carvings,[5] with inscriptions in Quranic script.[4][6] The mosque, in a walled enclosure, is made of interlocking coral blocks[6] with its hypostyle roof supported by cut-coral columns. With three entrances, the mosque has two prayer halls surrounded by antechambers on three sides. Its vaulted, decorated ceiling is indented in steps. Local master carpenters, known as maavadikaleyge, fashioned the mosque's woodwork, roof and interior, and its wall panels and ceilings have many culturally-significant examples of traditional Maldivian woodcarving and lacquerwork.[7] The mihrab, with a mimbar (pulpit) at one end, is a large chamber. The main building, used for daily prayers, is divided into three sections: the mihtab (used by the imam to lead the prayers), the medhu miskiy (the mosque's central area) and the fahu miskiy (the rear of the mosque). A long, carved 13th-century panel memorializes the introduction of Islam to Maldives.[4]

The mosque's adjoining large, round blue-and-white minaret (built in 1675) resembles a wedding cake,[6] with a wide base similar to a ship's funnel. Built of coral stones, it is braced with metal strips.[1] The minaret is surrounded by a graveyard with carved coral tombstones[5] distinguishing males, females, sultans and their families. Women's tombstones have rounded tops; men's have pointed tops, and inscriptions for royalty are gilt. For family members, small mausoleums with intricately-decorated stone walls were built.[4]

This mosque and the other Maldives coral mosques were added to the cultural UNESCO World Heritage tentative list in 2008 for meeting criteria two (use of sea cultures for creating unique architecture), three (a historic cultural tradition with no parallel elsewhere in the world), four (the tongue-in-groove technique shows a highly developed building level for the period) and six (the buildings are associated with both religious and social practices of cultural significance). According to the UNESCO appraisal, "The architecture, construction and accompanying artistry of the mosque and its other structures represent the creative excellence and achievement of the Maldivian people".[1]

Lacquerwork details

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Coral Stone Mosques of Maldives". UNESCO Organization. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Mauroof Jameel and Yahaya Ahmad (2016). Coral Stone Mosques of Maldives: The Vanishing Legacy of the Indian Ocean, p. 134. ORO Editions. ISBN 9780986281846.

- ^ a b West 2009, p. 493.

- ^ a b c d e Masters 2009, p. 97.

- ^ a b Chesshyre 2014, p. 170.

- ^ a b c "Malé Hukuru Miskiy (Malé Friday Mosque)". fodors.com. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

Bibliography

edit- Chesshyre, Tom (27 November 2014). Gatecrashing Paradise: Misadventures in the Real Maldives. Nicholas Brealey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85788-937-6.

- Masters, Tom (2009). Maldives. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74179-013-9.

- Neville, Adrian (1 January 1995). Malé, Capital of the Maldives. Novelty Printers and Publishers. ISBN 978-99915-3-018-5.

- West, Barbara A. (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- USA, IBP USA (1 January 2012). Maldives: Doing Business in Maldives for Everyone Guide – Practical Information and Contacts. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-4387-7268-4.