Mongalla or Mangalla is a Payam in Juba County, Central Equatoria State in South Sudan,[1] on the east side of the Bahr al Jebel or White Nile river. It lies about 75 km by road northeast of Juba. The towns of Terekeka and Bor lie downstream, north of Mongalla.

Mongalla | |

|---|---|

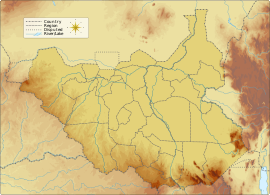

Map showing location of Mongalla in relation to the South Sudanese capital of Juba | |

| Coordinates: 5°11′56″N 31°46′10″E / 5.198933°N 31.769511°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Central Equatoria |

| County | Juba |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Climate | Aw |

During the colonial era, Mongalla was capital of Mongalla Province, which reached south to Uganda and east towards Ethiopia. On 7 December 1917 the last of the northern Sudanese troops were withdrawn from Mongalla, replaced by Equatorial troops. These southern and at least nominally Christian troops remained the only permanent garrison of the town and province until their mutiny in August 1955. Mongalla and the surrounding province was then absorbed into Equatoria Province in 1956. The town was taken and retaken more than once during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005).

An experimental station was established to grow sugar at Mongalla in the 1950s, and there were plans to establish commercial operations. However, after independence in 1956 the Khartoum government shifted the sugar project to the north, where it is grown under much less favorable conditions with heavy irrigation. A sugar, clothing, and a weaving factory was established in Mongalla in the 1970s but operations failed to get beyond their trial phase and diminished as conflict grew in the region in the early 1980s. In April 2006 the President of Southern Sudan, Salva Kiir Mayardit, named Mongalla as one of the Nile ports to be the first to be rehabilitated.

Mongalla is an important center for gauging the flow of the Nile, with measurements taken regularly from 1905 until 1983, and since 2004.

History and politics

editEarly colonial period

editAfter the final defeat of the Caliphate (Khalifa) by the British under General Herbert Kitchener in 1898, the Nile up to the Uganda border became part of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. An expedition upriver from Omdurman (Ondurman) arrived in December 1900. The post that had been established at Kiro was transferred to Mongalla in April 1901 since Kiro was claimed to be in Belgian territory.[2] During 1904 posts were established where needed in the Mongalla districts to suppress the activities of "Abyssinian brigands who infested the country".[2]

Until 1906 Mongalla province was part of the Upper Nile province, after which it became a separate administration.[3] The first governor was Angus Cameron, appointed in January 1906.[4] A party from the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) arrived the same month, but decided it was not suitable for a base and instead located the mission downstream at Bor.[5] The colonial administration opposed efforts by the CMS to convert the Bor and Bari people of Mongalla. The missionaries interpreted this as due to the influence of Islam in weakening the spiritual ideals of the officials.[6] Cameron desired to avoid friction with the Muslims who had undertaken most of the work of building and servicing the new provincial capital.[7]

In 1910 Theodore Roosevelt visited the province. Before his arrival, Governor R.C.R. Owen informed Governor General Sir Reginald Wingate that everything would be done for the former president of the United States, but also pointed out that his troops had not even one donkey.[8] Roosevelt's expedition reached Mongalla at the end of February, coming from the Belgian Congo via the Lado Enclave. He was impressed by the Egyptian and Sudanese troops, but when visiting a native dance he commented on the lack of middle-aged men, a result of the Mahdist wars that had ended over ten years ago.[9] In June 1910 the British Sudanese forces took over the Lado Enclave from the Belgians, becoming part of the province of Mongalla. [10]The Anglican and Roman Catholic missionaries requested that Sunday be retained as a sabbath at Lado, as it had been under the Belgians, rather than changed to Friday as it had in the rest of the Sudan. However, Governor Owen opposed retaining Sunday; he felt that the more "bigoted" Muslims in the army would object to working on Friday, and noted that all recruits to the army were instructed in the Muslim religion.[11]

A few months later, however, Owen proposed creation of an Equatorial battalion composed entirely of southerners. This force would be taught to follow English commands and the Christian faith, which would, over time, unite with Uganda and would prevent spread of the Muslim faith farther south. He was against Islam on the basis that it "may at any time break out into a wave of fanaticism". Owen's plan was approved by Wingate.[11] Wingate said "...we must remember that the bulk of the inhabitants ... are not Moslems (Muslims) at all, that the whole of Uganda has accepted Christianity almost without a murmur, and that furthermore English is a very much easier language to learn than Arabic...".[12]

In 1913, the government increased restrictions on private travel and immigrants, which meant anybody arriving in Mongalla and wishing to go north from the Uganda or the Belgian Congo could be examined for sleeping sickness by a medical officer. The maximum punishment for any breach of the new regulations was a £10 fine or a 6-month prison sentence.[13]

On 7 December 1917 the last of the northern Sudanese troops were withdrawn from Mongalla, replaced by Equatorial troops. These southern and at least nominally Christian troops remained the only permanent garrison of the town and province until their mutiny in August 1955.[11]

When Hasan Sharif, son of Khalifa Muhammad Sahif, was exiled to Mongalla in 1915 after taking place in a conspiracy in Omdurman, Governor Owen said "...I told him he is lucky to come and see this part of Sudan for nothing, when tourists pay hundreds of pounds ... I fear he doesn't see the joke...".[14] Owen retired in 1918.[15] Major Cecil Stephen Northcote succeeded him as Governor of Mongala from 1918 to 1919, then moved on to become Governor of the Nuba Mountains province.[16]

The Sudan was very lightly administered. As late as 1919 there were just 17 British administrators in the Bahr al-Ghazal and Mongalla provinces, with a combined area twice that of Britain.[17] In the early years, British officials depended on native officials for advice and to act as interpreters. However, they had to be careful about ethnic rivalries. Thus Fadl el-Mula, a Dinka who had been a police quartermaster, greatly impressed the Governor of Mongalla and was appointed assistant superintendent of the Twic Dinka in 1909. He was credited with keeping the peace between the Dinka and the Nuer people, two groups with a history of fighting and cattle raiding. However, Fadl el-Mula was so strongly biased towards the Dinka that his police were attacked by angry Nuer and he had to be removed from his post.[18]

The Arabic language and the Muslim religion continued to be spread in South Sudan by merchants and administrators from the North, and even by British officials who preferred to speak Arabic rather than learn the local language.[19] A rising by the Aliab Dinka in 1919 was suppressed harshly in 1920. That year the Nuer were attacking both the Dinka and the Burun people on the border with Ethiopia. The governor of Mongalla in 1920, V.R. Woodland, said that Mongalla at the time was "in such a muck-up state he doesn't know where to start".[20] Woodland called for a decision; either South Sudan should be separated from the north and administered as a territory in the same way as Uganda, or the British should encourage development by the Arabs within the structure of the North Sudan. Nothing was done.[19]

Later colonial period (1920–1956)

editThe Mongalla region suffered an outbreak of cerebrospinal meningitis (CSM) between 1918 and 1924, apparently introduced by Ugandan porters who had served in German East Africa during World War I. CSM caused high mortality for a six-year period as it spread from one family to another. A less devastating CSM epidemic started in 1926, causing 335 deaths in 1928, 446 in 1929 and 335 in the first three months of 1930 before rapidly dying out. Dr. Alexander Cruikshank of the Sudan Medical Services attributed the epidemic in part to poor housing conditions. The Azande people of the western part of the province avoided the disease. They had a better diet and less crowded quarters than the Dinka and Nuer people in the centre of the province.[21]

Airplanes began being used in the Sudan in the 1920s, with revolutionary effect on military and civilian administration. Flying was hazardous, however. On 4 July 1929 a Fokker FViib/3m owned by the Belgian financier Albert Lowenstein crashed at Mongalla. There were no deaths, but the plane was severely damaged.[22] A Singapore flying boat built by Short Brothers made a flight around Africa in 1929. Starting from Benghazi, the plane flew to Aboukir Bay, then up the Nile to Mongalla, which was reached at the end of January, and onward to Entebbe on Lake Victoria.[23]

During the 1920s the British steadily expanded control over the South Sudan. The Deputy governor of Mongalla, Major R.G.C. Brock, estimated that he had added 50,000 Toposa and related people to the eastern half of his province, a somewhat inflated figure.[24] By establishing strong central control, the British eroded whatever authority the traditional rulers may have had. In 1929 the British governor of Mongalla province said "the government support which can be given to the chiefs is not worth their while to have".[25]

In 1925 Major G.D. Gould was denied a license to prospect for gold and oil in the east of Mongalla province beyond the Didinga Hills. Travel in the Toposa country was dangerous without a large armed escort, and if the Ethiopians had got word of the survey they would have tried to occupy that part of the country.[26] The British began to follow an "Africanization" policy. A directive issued on 25 January 1930 by the Civil Secretary of Sudan to the governors of Upper Nile, Bahr al-Ghazal and Mongalla said: "The policy of the government in the southern Sudan is to build up series of self-contained racial or tribal units with structures and organization based to whatever extent the requirement of equity and good government permits, upon indigenous customs, traditional usage and beliefs".[27]

In 1930 the capital of Equatoria (southern Sudan) was transferred from Mongalla to Juba, further upstream to the south.[28] The governor of Mongalla province from 1930 until 1936 was Leonard Fielding Nalder, formerly governor of Fung province from 1927 to 1930.[29] In 1935 Nalder reported after a survey of his province that there was a general lack of tribal cohesion. Governor-General Sir Stewart Symes at Khartoum had little interest in development of the south of Sudan and he advised the local officials that chiefs should have territorial rather than ethnic authority.[30] In 1936 Mongalla and the Bahr al-Ghazal provinces were incorporated into the Equatoria province, with headquarters at Juba, with parts of Upper Nile province detached.[31]

Civil war

editSudan became independent in 1956, after the outbreak of the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972). After the Addis Ababa Agreement (1972) the Jieng Bor and Murle people lived in relative peace, sharing grazing areas, especially Gok Bor. In mid 1981 this harmony broke down when Murle bandits attacked Jieng Bor cattle camps in several locations around Mongalla. The police were called in by the commissioner of Mongalla, and turned against the Bor Dinka. The SPLM/A exploited this hostility to the Bor Dinka by some Equatorian tribes to gain recruits from the Dinka.[32] Peace broke down and the civil war resumed in 1983.

Early in 1985 the Southern Axis of the SPLA under Major Arok Thon Arok challenged government forces in Southern Upper Nile, Eastern Equatoria and Central Equatoria. The Southern Axis captured Owiny-ki-Bul and Mongalla without difficulty, then crossed the Nile, captured Terekeka and besieged Juba.[33] Later in 1985 the forces of the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) received a setback at the village of Gut-Makur near Mongalla when they were confronted by well-armed Mundari people. Although willing to fight the Sudan army, the Mundari were not willing to do so under Dinka leadership.[34]

In March 1989 Alternate Commander Jok Reng of the SPLA Mainstream recaptured Mongalla with a relatively small force.[35] In the last half of 1989 the SPLA consolidated in towns like Mongalla that surrounded Juba.[36] In late 1991, Mongalla was the scene of clashes between two arms of the SPLA. Riek Machar of the SPLM/A Nasir was pushing south towards Torit, while the SPLM/A Mainstream commander for Equatoria Kuol Manyang Juuk wanted to push Riek's forces back to Nuerland.[37] Due to disunity among the southerners, between 1991 and 1994 the NIR was able to recapture many places in South Sudan including Mongalla and also Ayod, Leer, Akobo, Pochalla, Pibor, Waat, Nasir, Kit, Palotaka, Yirol, Bor, Torit, Kapoeta, Parjok and Magwi.[38] Government forces coming from Bor took Mongalla in June 1992 and then turned east toward Torit.[39]

Post-civil war

editThe Second Sudanese Civil War finally ended in January 2005. However, Mongalla continued to suffer at the hands of the Lord's Resistance Army.[40] Due to the civil war, Mongalla had suffered considerable physical neglect and damage, and population loss. In April 2006 the President of Southern Sudan, Salva Kiir Mayardit, named Mongalla as one of the Nile ports to be the first to be rehabilitated. He warned that demands for reconstruction spending would be much greater than available funding, so work had to be prioritized.[41] Clearance of the Mongalla minefield was complete in July 2009.[42] Mongalla is an important center for gauging the flow of the Nile, with measurements taken regularly from 1905 until 1983. During most of the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) the gauging stopped, resuming in 2004.[43]

Geography and climate

editMongalla lies about 75 km (47 mi) by road northeast of Juba on the road to Bor in the north, but nearer 50 km (31 mi) as the crow flies.[44] Mongalla is situated on the east bank of the White Nile in Central Equatoria state at an altitude of 443 metres (1,455 ft).[45] Rainfall is relatively low between November and February, then increasing with two peaks in June and August. Annual precipitation is about 1,000 mm (40 in).[46] Winds are northerly in the dry season and southerly in the rainy season.[47] Based on observations taken between April 1903 and December 1905, the mean temperature was 26.4 °C (79.5 °F), with mean maximum 33.7 °C (92.6 °F) and mean minimum 20.9 °C (69.7 °F). Mean relative humidity was 74%.[45]

The river flowing past Mongalla combines seasonal torrential runoff in the rainy season with the more constant discharge from Lake Victoria, influenced by evaporation and by the damping and storage effects of Lake Albert, Lake Edward and Lake Kyoga.[48] The Sudd, a vast area of swampland, stretches downriver from Mongalla to near the point where the Sobat River joins the White Nile just upstream from Malakal. Due to evaporation, only half the water that enters the Sudd at Mongalla emerges from the northern end of the swamps.[49] The much smaller Badigeru Swamp lies about 32 km (20 mi) to the east, separated from Mongalla by a region of open grassland.[50] The belt along the Nile about 10 km wide and 146 km long from Mongalla to Bor is inhabited by the Mundari and Dinka peoples.[49]

Economic development

editThe district commissioners initiated the development of cotton at Mongalla in the 1920s and 1930s, but the price paid for Mongalla cotton fell from 50 piastres per kantar in 1929–30 to 18 piastres in 1931 and the industry failed to develop as planned.[51][52]The "Southern Scales", which defined the rates of pay for officials and workers in the southern provinces of Sudan, were extremely low, making it impossible for the administrators to undertake any development such as a school, hospital or economic projects. Use of money was restricted, and even in 1945 taxes were still being paid in kind.[53]

In 1937 J.C. Myers was commissioned to undertake a botanical survey of Mongalla province, later extended to all of Equatoria. In contrast to the pessimistic view of the south taken by the Khartoum administration, he was enthusiastic about the wealth and diversity of plants. He noted that the people had adapted to cultivating non-native plants such as cassava, maize, sweet potato and groundnuts. He also noted that the government was restricting commercial development of sugarcane, tobacco and coffee, which grew wild, and thus preventing economic development.[54] In 1938 Governor Symes made a tour of Equatoria and left with "contempt intensified". He consistently rejected schemes for development.[30]

An experimental station was established to grow sugar at Mongalla in the 1950s, and there were plans to establish commercial operations. However, after independence in 1956 the Khartoum government shifted the sugar project to the north, where it is grown under much less favorable conditions with heavy irrigation. After the First Sudanese Civil War ended in 1972, there were plans to revive sugar production at Mongalla, and although Mongalla Sugar Processing Factory operated on a low-scale in the 1970s, it ceased production when civil war broke out again in 1983.[55][56]A clothing mill also operated in the 1970s but was deactivated due to the unrest in the early 1980s.[55] A paper mill was also planned at Mongalla, to be fed by eucalyptus species planted in a 70,000 feddan area.[57]Equipment was supplied from Denmark between 1975 and 1976 for use in an agro-industrial complex at Mongalla. This would include a power station and pump station to support an abattoir, poultry project, fish-receiving plant and wood-working factory. The equipment arrived but was not installed, and eventually rusted away. A project funded by Khartoum also established six textile-manufacturing units in Sudan, one at Mongalla, and the other five factories located in the north at Ed Duiem, Kadugli, Kosti, Nyala, and Shendi. An agreement was made with a Belgian firm, SOBERI, to supply the weaving factory of 256 looms and at one point it was estimated to produce around 9 million meters of grey fabric per annum, but it failed to get past the trial phase due to lack of raw materials, capital, and transportation facilities.[58]

References

edit- ^ Kwajok, Lako Jada (29 May 2016). "Taking a closer look at the controversial 28 states". South Sudan Nation. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ a b Budge 2004, pp. 282.

- ^ Warburg 1971, pp. 139.

- ^ DNW.

- ^ Budge 2004, pp. 321.

- ^ Korieh & Njoku 2007, pp. 218.

- ^ Sanderson & Sanderson 1981, pp. 51.

- ^ Daly 2004, pp. 102.

- ^ Roosevelt 2005, pp. 453.

- ^ Chisholm 1922, pp. 615.

- ^ a b c Collins 2005, pp. 190.

- ^ Warburg 1971, pp. 122.

- ^ Bell 1999, pp. 140.

- ^ Warburg 1971, pp. 106.

- ^ Daly & Hogan 2005, pp. 204.

- ^ Daly & Hogan 2005, pp. 175.

- ^ Deng 1995, pp. 83.

- ^ Anderson & Killingray 1991, pp. 166.

- ^ a b Collins 2005, pp. 191.

- ^ Roberts, Fage & Oliver 1984, pp. 764.

- ^ Kohn 2008, pp. 264.

- ^ Daly & Hogan 2005, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Barnes & James 1989, pp. 203.

- ^ Collins 2005, pp. 242.

- ^ Collins 2005, pp. 185.

- ^ Collins 2005, pp. 245.

- ^ Jalata 2004, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Zeleza & Eyoh 2002, pp. 298.

- ^ Clayton 1969, pp. 341.

- ^ a b Daly 2003, pp. 41.

- ^ Daly 2003, pp. 12.

- ^ Guarak 2011, pp. 271.

- ^ Collins 2005, pp. 293.

- ^ Collins 2005, pp. 59.

- ^ Guarak 2011, pp. 315.

- ^ Guarak 2011, pp. 349.

- ^ Guarak 2011, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Guarak 2011, pp. 228.

- ^ Guarak 2011, pp. 378.

- ^ Sudan: Thousands flee food shortages ...

- ^ Kiir 2006.

- ^ Monthly situation report.

- ^ Awadalla 2011.

- ^ Google Maps (Map). Google.

- ^ a b Knox 2011, pp. 272.

- ^ Knox 2011, pp. 87.

- ^ Knox 2011, pp. 260.

- ^ HYDROC.

- ^ a b El Shamy 2010.

- ^ Molloy 1950.

- ^ Collins 2005, pp. 248.

- ^ Daly 2004, pp. 428.

- ^ Ruay 1994, pp. 41.

- ^ Daly 2003, pp. 91.

- ^ a b Guarak 2011, pp. 478.

- ^ Yongo-Bure 2007, pp. 38.

- ^ Yongo-Bure 2007, pp. 40.

- ^ Yongo-Bure 2007, pp. 56–59.

Sources

edit- Anderson, David M.; Killingray, David (1991). Policing the empire: government, authority, and control, 1830–1940. Manchester University Press ND. ISBN 0-7190-3035-8.

- Awadalla, Sirein Salah (June 2011). "Wetland Model in an Earth Systems Modeling Framework for Regional Environmental Policy Analysis" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Barnes, Christopher Henry; James, Derek N. (1989). Shorts aircraft since 1900. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-662-7.

- Bell, Heather (1999). Frontiers of medicine in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1899–1940. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820749-8.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (2004). The Egyptian Sudan: Its History and Monuments Part Two. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4179-8280-2.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1922). The Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information. The Encyclopædia Britannica Co.

- Clayton, Sir Gilbert Falkingham (1969). An Arabian diary. University of California Press. p. 341.

- Collins, Robert O. (2005). Civil wars and revolution in the Sudan: essays on the Sudan, Southern Sudan and Darfur, 1962 – 2004. Tsehai Publishers. ISBN 0-9748198-7-5.

- Daly, M. W. (2003). Imperial Sudan: The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium 1934–1956. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53116-0.

- Daly, M. W. (2004). Empire on the Nile: The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898–1934. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89437-9.

- Daly, M. W.; Hogan, Jane (2005). Images of empire: photographic sources for the British in the Sudan. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-14627-X.

- Deng, Francis Mading (1995). War of visions: conflict of identities in the Sudan. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1793-8.

- DNW. "Lieutenant-Colonel Angus Cameron". Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- El Shamy, Mohamed; et al. (2010). "GIS Based Decision Support Tool for Sustainable Development of SUDD Marches Region (Sudan)" (PDF). Nile Basin Capacity Building Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Guarak, Mawut Achiecque Mach (2011). Integration and Fragmentation of the Sudan: An African Renaissance. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4567-2355-2.

- HYDROC. "Hindasting and Calibration of Mongalla Gauge Flows". Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Jalata, Asafa (2004). State crises, globalisation, and national movements in north-east Africa. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34810-2.

- Kiir, Salava (April 11, 2006). "TEXT- Salava Kiir statement before South Sudan parliament". Sudan Tribune. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Knox, Alexander (2011). The Climate of the Continent of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60071-3.

- Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-6935-4.

- Korieh, Chima Jacob; Njoku, Raphaël Chijioke (2007). Missions, states, and European expansion in Africa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-95559-1.

- Molloy, Lt. Colonel P. (February 1950). "The Bedigeru or Badingilu Swamp".

- "Monthly situation report" (PDF). The United Nations Mine Action Office in Sudan. July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Roberts, Andrew D.; Fage, John Donnelly; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1984). The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22505-1.

- Sanderson, Lilian Passmore; Sanderson, Neville (1981). Education, religion & politics in Southern Sudan, 1899–1964. Ithaca Press. ISBN 0-903729-63-6.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (2005). African Game Trails: An Account of the African Wanderings of an American Hunter, Naturalist. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4179-7537-7.

- Ruay, Deng D. Akol (1994). The politics of two Sudans: the south and the north, 1821–1969. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 91-7106-344-7.

- "Sudan: Thousands flee food shortages and Ugandan rebel attacks in the south". Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN) Report from ReliefWeb. 16 May 2005. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013.

- Warburg, Gabriel (1971). The Sudan under Wingate: administration in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1899–1916. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-2612-0.

- Yongo-Bure, Benaiah (2007). Economic development of southern Sudan. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-3588-2.

- Zeleza, Paul Tiyambe; Eyoh, Dickson (2002). "Juba, Sudan". Encyclopedia of Twentieth-century African History. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-98657-1.