Henning Georg Mankell (Swedish pronunciation: [ˈhɛ̂nːɪŋ ˈmǎŋːkɛl]; 3 February 1948 – 5 October 2015) was a Swedish crime writer, children's author, and dramatist, best known for a series of mystery novels starring his most noted creation, Inspector Kurt Wallander. He also wrote a number of plays and screenplays for television.

Henning Mankell | |

|---|---|

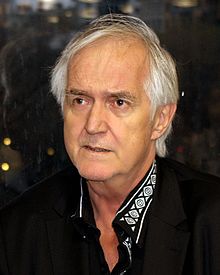

Henning Mankell in New York City in April 2011 | |

| Born | Henning Georg Mankell 3 February 1948 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Died | 5 October 2015 (aged 67) Gothenburg, Sweden |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, publisher |

| Period | 1991–2009 (Kurt Wallander series) |

| Genre | Crime fiction Thriller |

| Notable works | The Kurt Wallander novels |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Ingmar Bergman (father-in-law) |

He was a left-wing social critic and activist. In his books and plays he constantly highlighted social inequality issues and injustices in Sweden and abroad. In 2010, Mankell was on board one of the ships in the Gaza Freedom Flotilla that was boarded by Israeli commandos. He was below deck on the MV Mavi Marmara when nine civilians were killed in international waters.

Mankell shared his time between Sweden and countries in Africa, mostly Mozambique where he started a theatre. He made considerable donations to charity organizations, mostly connected to Africa.

Life and career

editMankell's grandfather, also named Henning Mankell, lived from 1868 to 1930 and was a composer.[1] Mankell was born in Stockholm, Sweden in 1948. His father Ivar was a lawyer who divorced his mother when Mankell was one year old. He and an older sister lived with his father for most of their childhood. The family first lived in Sveg, Härjedalen in northern Sweden, where Mankell's father was a district judge. In the biography on Mankell's website, he describes this time when they lived in a flat above the court as one of the happiest in his life.[2] In Sveg, a museum was built in his honour during his lifetime.[3]

Later, when Mankell was thirteen, the family moved to Borås, Västergötland on the Swedish west coast near Gothenburg.[2] After three years he dropped out of school and went to Paris when he was 16. Shortly afterwards he joined the merchant marine, working on a cargo ship and he "loved the ship's decent hard-working community".[2] In 1966, he returned to Paris to become a writer. He took part in the student uprising of 1968. He later returned to work as a stagehand in Stockholm.[3] At the age of 20, he had already started as author at the National Swedish Touring Theatre in Stockholm.[4] In the following years he collaborated with several theatres in Sweden. His first play, The Amusement Park dealt with Swedish colonialism in South America.[2] In 1973, he published The Stone Blaster, a novel about the Swedish labour movement. He used the proceeds from the novel to travel to Guinea-Bissau. Africa would later become a second home to him, and he spent a big part of his life there. When his success as a writer made it possible, he founded and ran a theatre in Mozambique.[2]

From 1991 to 2013, Mankell wrote the books which made him famous worldwide, the Kurt Wallander mystery novels. Wallander was a fictional detective living in Ystad in southern Sweden, who supervised a squad of detectives in solving murders, some of which were bizarre. As they worked to catch a killer who had to be stopped before he could kill again, the team often worked late into the nights in a heightened atmosphere of tension and crisis. Wallander's thoughts and worries about his daughter, his health, his lack of friends and a social life, his worries about Swedish society, shared his mental life with his many concerns and worries about the case he was working. There were ten books in the series. They were translated into many languages and sold millions of copies worldwide. The series gave Mankell the freedom and wherewithal to pursue other projects which interested him.

After living in Zambia and other African countries, Mankell was invited from 1986 onward to become the artistic director of Teatro Avenida in Maputo, Mozambique. He subsequently spent extended periods in Maputo working with the theatre and as a writer. He built his own publishing house, Leopard Förlag, in order to support young talented writers from Africa and Sweden.[5] His novel Chronicler of the Winds, published in Sweden as Comédie infantil in 1995, reflects African problems and is based on African storytelling.[6] On 12 June 2008, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate from the University of St Andrews in Scotland "in recognition of his major contribution to literature and to the practical exercise of conscience".[7]

Around 2008, Mankell developed two original stories for the German police series Tatort. Actor Axel Milberg, who portrays Inspector Klaus Borowski, had asked Mankell to contribute to the show when they were promoting The Man from Beijing audiobook, a project that Milberg had worked on. The episodes were scheduled to broadcast in Germany in 2010.[8][9] In 2010, Mankell was set to work on a screenplay for Sveriges Television about his father-in-law, movie and theatre director Ingmar Bergman, on a series produced in four one-hour episodes. Mankell pitched the project to Sveriges Television and production was planned for 2011.[10] At the time of his death, Mankell had written over 40 novels that had sold more than 40 million copies worldwide.[11]

Personal life

editMankell was married four times and had four sons, Thomas, Marius, Morten and Jon, by different relationships. In 1998 he married Eva Bergman, daughter of film director Ingmar Bergman. They remained married until his death in 2015.[3]

Death

editIn January 2014, Mankell announced that he had been diagnosed with lung cancer and throat cancer.[12] In May 2014, he reported that treatments had worked well and he was getting better.[13][14]

He wrote a series of articles inspired by his wife Eva, describing his situation, how it felt to be diagnosed,[15] how it felt to be supported,[16] how it felt to wait,[17] and after his first chemotherapy at Sahlgrenska University Hospital about the importance of cancer research.[18] Three weeks before his death he wrote about what happens to people's identity when they are stricken by a serious illness.[19] His last post was published posthumously 6 October.[20]

On 5 October 2015, Mankell died at the age of 67, almost two years after having been diagnosed.[21]

Political views

editWe refuse to understand the significance of Islamic culture in Europe's history. We are characterized by intense ignorance. What would Europe have been without Islamic culture? Nothing.

Henning Mankell, Dagbladet, 30 August 2007 (talking about his play Lampedusa which tells about a Muslim lesbian immigrant in Sweden)[22]

In his youth Mankell was a left-wing political activist and participated in the Protests of 1968 in Sweden, protesting against, among other things, the Vietnam War, the Portuguese Colonial War, and the apartheid regime in South Africa. Furthermore, he got involved with Folket i Bild/Kulturfront which focused on cultural policy studies.[23] In the 1970s, Mankell moved from Sweden to Norway and lived with a Norwegian woman who was a member of the Maoist Workers' Communist Party. He took an active part in their activities but did not join the party.[24]

In 2002, Mankell gave financial support by buying stocks for 50,000 NOK in the Norwegian left-wing newspaper Klassekampen.[25] In 2009, Mankell was a guest at the Palestine Festival of Literature. He said he had seen "repetition of the despicable apartheid system that once treated Africans and coloured as second-class citizens in their own country". He found a resemblance between the Israeli West Bank barrier and the Berlin Wall: "The wall that is currently dividing the country will prevent future attacks, in short term. In the end, it will face the same destiny as the wall that once divided Berlin did."[26] Considering the environment the Palestinian people live in, he continued: "Is it strange that some of them in pure desperation, when they cannot see any other way out, decide to become suicide bombers? Not really? Maybe it is strange that there are not more of them."[26]

Mankell stated in an interview with Haaretz that he did not support Hezbollah.[27] In Mankell's opinion the state of Israel should not have a future as a two-state solution and this "will not be the end of the historical occupation". He said he did not encounter antisemitism during his journey, just "hatred against the occupants that is completely normal and understandable", and said that "to keep these two things separate is crucial".[26]

Gaza flotilla

editIn 2010, Henning Mankell was on board the MS Sofia, one of the boats which took part in the flotilla which tried to break the Israeli embargo of the Gaza strip.[28] Following the Israel Defense Forces' boarding of the flotilla on the morning of 31 May 2010, Mankell was deported to Sweden. He subsequently called for global sanctions against Israel.[29] In 2010 it was reported that he was considering halting Hebrew translations of his books.[30] In June 2011, Mankell stated in an article in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz that he had never considered preventing his books from being translated into Hebrew, and that unidentified persons had stolen his identity to make this false claim.[27]

Mankell was supposed to be one of twenty Swedish participants in "Freedom Flotilla II" which never took place.[31] It was originally scheduled to sail to Gaza in June 2011.[32]

Charity and legacy

editThere are too many people in the world who just sit and watch their money pile up, that is very hard for me to understand.

Henning Mankell[33]

In 2007, Henning Mankell donated 15 million Swedish crowns (about 1.5 million euros) to SOS Children's Villages for a children's village in Chimoio in western Mozambique.[34] Mankell donated vast amounts of money to charitable organizations such as SOS Children's Villages and Hand in Hand,[35] a collection of independent organizations.[36]

In the 1980s, Mankell visited United Nations refugee camps in Mozambique and later accompanied UN High Commissioner Sadako Ogata to refugee camps in South Africa. In 2013, he visited Congolese refugees in Uganda. He wrote on the plight of refugees and after his death his website asked for donations in his name to the UN Commission on Refugees.[37]

The theme for short stories submitted to the inaugural Festival Fim do Caminho Literary Prize, "Crime in Mozambique", was chosen in homage to Mankell.[38][39]

Works

editWallander series

editKurt Wallander is a fictional police inspector living and working in Ystad,[40] Sweden. In the novels, he solves shocking murders with his colleagues. The novels have an underlying question: "What went wrong with Swedish society?"[41]

The series has won many awards, including the German Crime Prize and the British 2001 CWA Gold Dagger for Sidetracked (1995).[42]

The ninth book, The Pyramid (1999), is a prequel about Wallander's past, covering the time until just before the start of Faceless Killers (1991). It includes a collection of five novellas:[42]

- Wallander's First Case

- The Man with the Mask

- The Man on the Beach

- The Death of the Photographer

- The Pyramid

Ten years after The Pyramid, Mankell published another Wallander novel, The Troubled Man (2009), which he said would definitely be the last in the series.[42]

Linda is the daughter of Kurt Wallander, who follows in his footsteps as a police officer. Mankell began an intended trilogy of novels with her as the protagonist. However, following the suicide of Johanna Sällström, the actress playing the character at the time in the Swedish TV series, Mankell was so distraught that he decided to abandon the series after only the first novel.[43]

Bibliography

editCrime fiction

editWallander series

edit- Mördare utan ansikte (1991; English translation by Steven T. Murray: Faceless Killers, 1997)

- Hundarna i Riga (1992; English translation by Laurie Thompson: The Dogs of Riga, 2001)

- Den vita lejoninnan (1993; English translation by Laurie Thompson: The White Lioness, 1998)

- Mannen som log (1994; English translation by Laurie Thompson: The Man Who Smiled, 2005)

- Villospår (1995; English translation by Steven T. Murray: Sidetracked, 1999) Gold Dagger 2001

- Fotografens död (1996; English translation included in The Pyramid as The Death of the Photographer)

- Den femte kvinnan (1996; English translation by Steven T. Murray: The Fifth Woman, 2000)

- Steget efter (1997; English translation by Ebba Segerberg: One Step Behind, 2002)

- Brandvägg (1998; English translation by Ebba Segerberg: Firewall, 2002)

- Pyramiden (1999; short stories; English translation by Ebba Segerberg with Laurie Thompson: The Pyramid, 2008)

- Mannen på stranden (2000; included in The Pyramid as The Man on the Beach)

- Handen (2004; novella; originally published in Dutch (2004) as Het Graf (The Grave).[44] Published in Swedish, 2013. English translation by Laurie Thompson: An Event in Autumn, 2014)

- Den orolige mannen (2009; English translation by Laurie Thompson: The Troubled Man, 2011)[45]

Linda Wallander

edit- Innan frosten (2002; English translation by Ebba Segerberg: Before the Frost, 2005)

Other crime novels

edit- Danslärarens återkomst (2000; English translation by Laurie Thompson: The Return of the Dancing Master, 2004)

- Kennedys hjärna (2005; English translation by Laurie Thompson: Kennedy's Brain, 2007, U.S. release)

- Kinesen (2007; English translation by Laurie Thompson: The Man from Beijing, 2010)

Other fiction

edit- Bergsprängaren (1973); English translation by George Goulding: The Rock Blaster, (2020)

- Vettvillingen (1977)

- Fångvårdskolonin som försvann (1979)

- Dödsbrickan (1980)

- En seglares död (1981)

- Daisy Sisters (1982)

- Sagan om Isidor (1984)

- Leopardens öga (1990); English translation by Steven T. Murray: The Eye of the Leopard, (2008)

- Comédia infantil (1995); English translation by Tiina Nunnally: Chronicler of the Winds, (2006)

- Vindens son (2000); English translation by Steven T. Murray: Daniel (2010)

- Tea-Bag (2001) English translation by Ebba Segerberg: The Shadow Girls (2012)

- Djup (2004); English translation by Laurie Thompson: Depths, (2006)

- Italienska skor (2006); English translation by Laurie Thompson: Italian Shoes (2009)

- Minnet av en smutsig ängel (2011); English translation by Laurie Thompson: A Treacherous Paradise, (2013)

- Svenska gummistövlar (2015); English translation by Marlaine Delargy: After the Fire, (2017)

Essays

edit- Kvicksand (2014) part memoir, part collection of essays, English translation by Laurie Thompson: Quicksand: What It Means to Be a Human Being

Children's books

editSofia series

edit- Secrets in the Fire – 2000 (Eldens hemlighet, 1995)

- Playing with Fire – 2002 (Eldens gåta, 2001)

- The Fury in the Fire – 2009 (Eldens vrede, 2005)

Joel Gustafsson series

edit- A Bridge to the Stars – 2005 (Hunden som sprang mot en stjärna – 1990)

- Shadows in the Twilight – 2007 (Skuggorna växer i skymningen – 1991)

- When the Snow Fell – 2007 (Pojken som sov med snö i sin säng – 1996)

- The Journey to the End of the World – 2008 (Resan till världens ände – 1998)

Young children's books

edit- The Cat Who Liked Rain – 2007

Film and television

editOriginal screenplays for television and TV

edit- Etterfølgeren (The Successor) (1997 film)[46]

- Labyrinten (2000), TV mini-series

- Talismanen (2003), TV mini-series (co-written with Jan Guillou)

- Unnamed Ingmar Bergman docudrama (2012), TV mini-series[47]

Film and television adaptations of novels

edit- Wallander (1997–2007) Sveriges Television. Swedish language.

- Wallander (2005, 2009, 2013) Yellow Bird for TV4 (Sweden). Swedish language.

- Wallander (2008, 2010, 2012, 2016) Yellow Bird for BBC (UK). English language.

Plays

edit- Älskade syster (1983) (Beloved Sister)

- Antiloperna (The Antelopes)

- Apelsinträdet (1983) (The Orange Tree)

- Att Storma Himlen (To Storm Heaven)

- Berättelser På Tidens Strand (Tales On The Beach of Time)

- Bergsprängaren (1973) (The Rock Blaster)

- Butterfly Blues

- Daisy Sisters (1982)

- Darwins kapten (2010) (Darwin's Captain)

- Den Samvetslöse Mördaren Hasse Karlsson... (The Ruthless Killer Hasse Karlsson...)

- Dödsbrickan (1980) (The Death Counter)

- Eldens gåta (2001) (Fire Riddle)

- En Gammal Man Som Dansar (Old Man Dancing)

- En Höstkväll Innan Tystnaden (An Evening in Autumn Before Silence)

- En seglares död (1981) (Death of a Sailor)

- Fångvårdskolonin som försvann (1979) (The Penal Colony Which Disappeared)

- Gatlopp (Running the Gauntlet)

- Grävskopan (The Excavator)

- Hårbandet (The Ribbon)

- I sand och i lera (1999) (In Sand and Mud)

- In Duisternis (2010) (Time of Darkness)

- Innan Gryningen (Before Dawn)

- Italienska skor (2006) (Italian Shoes)

- Jag dör, men minnet lever (2003) (I Die, but the Memory Lives)

- Kakelugnen På Myren (The Cocklestove on the Myre)

- Katten som älskade regn (1992) (The Cat that Loved Rain)

- Labyrinten (2000) (The Labyrinth)

- Lampedusa

- Mannen Som Byggde Kojor (The Man Who Built huts)

- Mörkertid (Dark Times)

- Möte Om Eftermiddagen (Afternoon Rendezvous)

- Och Sanden Ropar... (Sand Calling...)

- Påläggskalven (Groomed for Greatness)

- Pojken som sov med snö i sin säng (1996) (The Boy Who Slept with Snow in His Bed)

- Politik (2010) (Politics)

- Resan till värdens ände (1998) (Journey to The End of the World)

- Sagan om Isidor (1984) (Isidor's Saga)

- Sandmålaren (1974) (Sand painter)

- Svarte Petter (The Short Straw)

- Tea-Bag (2001)

- Tokfursten (The Silly Prince)

- Tyckte Jag Hörde Hundar (Thought I Heard Dogs)[48]

- Valpen (The Welp)

- Vettvillingen (1977) (The Maniac)

Awards and honours

edit- 1991 – Swedish Crime Writers' Academy, Best Swedish Crime Novel Award for Faceless Killers

- 1991 – Nils Holgersson Plaque for A Bridge to the Stars

- 1992 – Glass Key award For Best Nordic Crime Novel: Faceless Killers

- 1993 – Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis for A Bridge to the Stars

- 1995 – Swedish Crime Writers' Academy, Best Swedish Crime Novel Award for Sidetracked

- 1996 – Astrid Lindgren Prize

- 2001 – Crime Writers' Association Gold Dagger for Best Crime Novel of the Year: Sidetracked

- 2001 – Corine Literature Prize for One Step behind

- 2004 – Toleranzpreis der Evangelischen Akademie Tutzing

- 2005 – Gumshoe Award for Best European Crime Novel: The Return of the Dancing Master

- 2008 – Corine Literature Prize for the German Audiobook The Man from Beijing

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Sveg". henningmankell.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Henning Mankell. "Henning Mankell: Biography". Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Richard Orange (4 October 2015). "Henning Mankell obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Schottenius, Maria (27 September 2014). "Henning Mankell: Det var en livskatastrof". Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Damen, Jos (16 April 2006). "Henning Mankell (1948–2015) & Africa". African Studies Centre Leiden. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Cowell, Alan (21 April 2006). "In a Break From Mystery Writing, Henning Mankell Turns to Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Alison Flood; David Crouch (5 October 2015). "Henning Mankell, Swedish author of Wallander, dies at 67". TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Berühmte Autoren: Henning Mankell schreibt zwei "Tatort"-Krimis – Die Welt". Die Welt (in German). 6 November 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Günter Fink (13 December 2009). "Ironie macht die Dinge oft einfacher". Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Amster, Harry (21 December 2009). "Bergmans liv blir tv-drama". SvD.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Henning Mankell website" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Richard Orange (29 January 2014). "Henning Mankell, Wallander author, reveals cancer". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ HENNING MANKELL (29 January 2014). "Del 1: "En strid ur livets perspektiv"". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Swedish writer, pro-Palestinian activist Henning Mankell dies at 67". The Times of Israel. 5 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Henning Mankell (12 February 2014). "Henning Mankell: how it feels to be diagnosed with cancer". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Henning Mankell (22 March 2015). "Henning Mankell: No one should have to face cancer alone'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Henning Mankell (27 April 2014). "Henning Mankell: A bad night before my cancer test results". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Henning Mankell (22 May 2015). "Henning Mankell: the importance of cancer research". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Henning Mankell (16 September 2015). "Henning Mankell on living with cancer: there are days full of darkness". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Henning Mankell (6 October 2015). "Henning Mankell: 'Eventually the day comes when we all have to go'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ "Henning Mankell är död". svt.se. 5 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "- Teatret er i krise – Litteratur – Dagbladet.no". Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Tekstarkiv". Dagbladet. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Augustsson, Lars Åke; Hansén, Stig (2001). De svenska maoisterna (in Swedish). Gothenburg: Lindelöw. ISBN 91-88144-48-8.

- ^ "NRK.no – Her & Nå". NRK. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Ending Apartheid". P U L S E. 27 June 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Will the Real Henning Mankell Speak Up?". Haaretz.com. June 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Flood, Alison (31 May 2010). "Author Henning Mankell aboard Gaza flotilla stormed by Israeli troops". The Guardian.

- ^ Robert Booth; Kate Connolly; Tom Phillips; Helena Smith (2 June 2010). "Gaza flotilla raid: 'We heard gunfire – then our ship turned into lake of blood'". The Guardian.

- ^ Johan Nylander. "Henning Mankell may halt Hebrew book version". Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Crime writer Mankell will be on next Gaza aid flotilla". Yahoo! News. Stockholm. Agence France-Presse. 25 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

Swedish crime writer Henning Mankell will take part in the next international flotilla that will attempt to bring aid to Gaza at the end of June, organisers said Wednesday.

- ^ "Freedom Flotilla 2 to sail for Gaza by end of June". Almasry Alyoum. MENA. 10 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

The international steering committee of Freedom Flotilla 2, a planned convoy of ships aiming to bring material and moral support to the besieged people of Gaza, announced on Tuesday that the flotilla's intended launch date is to be postponed until June.

- ^ "Chimoio". henningmankell.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Africa. Chimoio". Henningmankell.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- ^ "2,151,238 jobs so far". www.handinhandinternational.org. Hand in Hand International. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Henning Mankell". Dagens Industri. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Jos Damen (6 October 2015). "Henning Mankell (1948–2015) & Africa". Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Competition and Forum 2016, Fim do Caminho.

- ^ "Homage to Henning Mankell", Press Release: Fim do Caminho Literary Prize, Mozambique. Miles Morland Foundation.

- ^ pronounced Ue-stad ("ue" as in "muesli" and "a" as in "father" – not pronounced as in the recent 2008 UK television adaptation)

- ^ Van der Paal, Jill. "Mördarna i Henning Mankells Kurt Wallanderserie" (PDF). www.lib.urgent.be. Universiteit Gent. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Wroe, Nicholas (20 February 2010), "A Life in writing: Henning Mankell", The Guardian.

- ^ Paul Gallagher (26 December 2009). "Henning Mankell creates a 'female Wallander' following star's suicide". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "The Grave: A Kurt Wallander Mystery by Henning Mankell". Inspector-Wallander.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Ny bok om Kurt Wallander". Svenska. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Etterfølgeren – English". www.nfi.no. Retrieved 27 January 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mankell to develop Ingmar Bergman drama". Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Författare: Colombine Teaterförlag". Colombine Teaterförlag. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

External links

edit- Official website

- Henning Mankell at IMDb

- Comprehensive Henning Mankell fan site Archived 20 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Branagh's Wallander – Website relating to the BBC's English-language Wallander starring Kenneth Branagh and Swedish versions with Krister Henriksson and Rolf Lassgärd

- Henning Mankell: the artist of the Parallax View – Slavoj Zizek

- The Mirror of Crime: Henning Mankell interview at Tangled Web (5/2001)

- Guardian Interview (11/2003)

- Henning Mankell on Gaza flotilla attack: 'I think they went out to murder', The Guardian 3 June 2010

- Henning Mankell: My responsibility is to react: video interview by Louisiana Channel, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in 2012.

- John Burnside: Quicksand by Henning Mankell review / uplifting, serious reflections on what it means to be human The Guardian 11 February 2016