Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp (UK: /ˈdjuːʃɒ̃/, US: /djuːˈʃɒ̃, djuːˈʃɑːmp/;[1] French: [maʁsɛl dyʃɑ̃]; 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) was a French painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art.[2][3][4] He is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the 20th century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture.[5][6][7][8] He has had an immense impact on 20th- and 21st-century art, and a seminal influence on the development of conceptual art. By the time of World War I, he had rejected the work of many of his fellow artists (such as Henri Matisse) as "retinal", intended only to please the eye. Instead, he wanted to use art to serve the mind.[9]

Marcel Duchamp | |

|---|---|

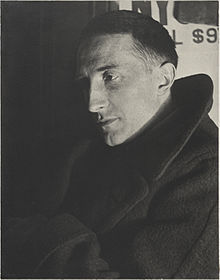

Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1920–21 by Man Ray, Yale University Art Gallery | |

| Born | Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp 28 July 1887 Blainville-Crevon, France |

| Died | 2 October 1968 (aged 81) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, film |

| Notable work | Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) Fountain (1917) The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923) LHOOQ (1919) Étant donnés (1946–1966) |

| Movement | Cubism, Dada, conceptual art |

| Spouses | |

| Partner(s) | Mary Reynolds (1929–1946) Maria Martins (1946–1951) |

Early life and education

editDuchamp was born at Blainville-Crevon in Normandy, France, to Eugène Duchamp and Lucie Duchamp (formerly Lucie Nicolle) and grew up in a family that enjoyed cultural activities. The art of painter and engraver Émile Frédéric Nicolle, his maternal grandfather, filled the house, and the family liked to play chess, read books, paint, and make music together.

Of Eugene and Lucie Duchamp's seven children, one died as an infant and four became successful artists. Marcel Duchamp was the brother of:

- Jacques Villon (1875–1963), painter, printmaker

- Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876–1918), sculptor

- Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti (1889–1963), painter.

As a child, with his two elder brothers already away from home at school in Rouen, Duchamp was closer to his sister Suzanne, who was a willing accomplice in games and activities conjured by his fertile imagination. At eight years old, Duchamp followed in his brothers' footsteps when he left home and began schooling at the Lycée Pierre-Corneille, in Rouen. Two other students in his class also became well-known artists and lasting friends: Robert Antoine Pinchon and Pierre Dumont.[10] For the next eight years, he was locked into an educational regime which focused on intellectual development. Though he was not an outstanding student, his best subject was mathematics and he won two mathematics prizes at the school. He also won a prize for drawing in 1903, and at his commencement in 1904 he won a coveted first prize, validating his recent decision to become an artist.

He learned academic drawing from a teacher who unsuccessfully attempted to "protect" his students from Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and other avant-garde influences. However, Duchamp's true artistic mentor at the time was his brother Jacques Villon, whose fluid and incisive style he sought to imitate. At 14, his first serious art attempts were drawings and watercolors depicting his sister Suzanne in various poses and activities. That summer he also painted landscapes in an Impressionist style using oils.

Early work

editDuchamp's early art works align with Post-Impressionist styles. He experimented with classical techniques and subjects. When he was later asked about what had influenced him at the time, Duchamp cited the work of Symbolist painter Odilon Redon, whose approach to art was not outwardly anti-academic, but quietly individual.

He studied art at the Académie Julian[12][13] from 1904 to 1905, but preferred playing billiards to attending classes. During this time, Duchamp drew and sold cartoons which reflected his ribald humor. Many of the drawings use verbal puns (sometimes spanning multiple languages), visual puns, or both. Such play with words and symbols engaged his imagination for the rest of his life.

In 1905, he began his compulsory military service with the 39th Infantry Regiment,[14] working for a printer in Rouen. There he learned typography and printing processes—skills he would use in his later work.

Owing to his eldest brother Jacques' membership in the prestigious Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture Duchamp's work was exhibited in the 1908 Salon d'Automne, and the following year in the Salon des Indépendants. Fauves and Paul Cézanne's proto-Cubism influenced his paintings, although the critic Guillaume Apollinaire—who was eventually to become a friend—criticized what he called "Duchamp's very ugly nudes" ("les nus très vilains de Duchamp").[15][16][17] Duchamp also became lifelong friends with exuberant artist Francis Picabia after meeting him at the 1911 Salon d'Automne, and Picabia proceeded to introduce him to a lifestyle of fast cars and "high" living.

In 1911, at Jacques' home in Puteaux, the brothers hosted a regular discussion group with Cubist artists including Picabia, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Roger de La Fresnaye, Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris, and Alexander Archipenko. Poets and writers also participated. The group came to be known as the Puteaux Group, or the Section d'Or. Uninterested in the Cubists' seriousness, or in their focus on visual matters, Duchamp did not join in discussions of Cubist theory and gained a reputation of being shy. However, that same year he painted in a Cubist style and added an impression of motion by using repetitive imagery.

During this period, Duchamp's fascination with transition, change, movement, and distance became manifest, and as many artists of the time, he was intrigued with the concept of depicting the fourth dimension in art.[18] His painting Sad Young Man on a Train embodies this concern:

First, there's the idea of the movement of the train, and then that of the sad young man who is in a corridor and who is moving about; thus there are two parallel movements corresponding to each other. Then, there is the distortion of the young man—I had called this elementary parallelism. It was a formal decomposition; that is, linear elements following each other like parallels and distorting the object. The object is completely stretched out, as if elastic. The lines follow each other in parallels, while changing subtly to form the movement, or the form of the young man in question. I also used this procedure in the Nude Descending a Staircase.[19]

In his 1911 Portrait of Chess Players (Portrait de joueurs d'échecs) there is the Cubist overlapping frames and multiple perspectives of his two brothers playing chess, but to that Duchamp added elements conveying the unseen mental activity of the players.

Works from this time also included his first "machine" painting, Coffee Mill (Moulin à café) (1911), which he gave to his brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon. The later more figurative machine painting of 1914, Chocolate Grinder (Broyeuse de chocolat), prefigures the mechanism incorporated into the Large Glass on which he began work in New York the following year.[20]

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2

editDuchamp's first work to provoke significant controversy was Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Nu descendant un escalier n° 2) (1912). The painting depicts the mechanistic motion of a nude, with superimposed facets, similar to motion pictures. It shows elements of the fragmentation and synthesis of the Cubists, as well as the movement and dynamism of the Futurists.

He first submitted the piece to appear at the Cubist Salon des Indépendants, but Albert Gleizes (according to Duchamp in an interview with Pierre Cabanne, p. 31)[21] asked Duchamp's brothers to have him voluntarily withdraw the painting, or to paint over the title that he had painted on the work and rename it something else. Duchamp's brothers did approach him with Gleizes' request, but Duchamp quietly refused. However, there was no jury at the Salon des Indépendants and Gleizes was in no position to reject the painting.[21] The controversy, according to art historian Peter Brooke, was not whether the work should be hung or not, but whether it should be hung with the Cubist group.[21]

Of the incident Duchamp later recalled, "I said nothing to my brothers. But I went immediately to the show and took my painting home in a taxi. It was really a turning point in my life, I can assure you. I saw that I would not be very much interested in groups after that."[22] Yet Duchamp did appear in the illustrations to Du "Cubisme", he participated in the La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House), organized by the designer André Mare for the Salon d'Automne of 1912 (a few months after the Indépendants); he signed the Section d'Or invitation and participated in the Section d'Or exhibition during the fall of 1912. The impression is, Brooke writes, "it was precisely because he wished to remain part of the group that he withdrew the painting; and that, far from being ill treated by the group, he was given a rather privileged position, probably through the patronage of Picabia".[21]

The painting was exhibited for the first time at Galeries Dalmau, Exposició d'Art Cubista, Barcelona, 1912, the first exhibition of Cubism in Spain.[23] Duchamp later submitted the painting to the 1913 "Armory Show" in New York City. In addition to displaying works of American artists, this show was the first major exhibition of modern trends coming out of Paris, encompassing experimental styles of the European avant-garde, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. American show-goers, accustomed to realistic art, were scandalized, and the Nude was at the center of much of the controversy.

Leaving "retinal art" behind

editAt about this time, Duchamp read Max Stirner's philosophical tract, The Ego and Its Own, the study which he considered another turning point in his artistic and intellectual development. He called it "a remarkable book ... which advances no formal theories, but just keeps saying that the ego is always there in everything."[24]

While in Munich in 1912, he painted the last of his Cubist-like paintings. He started The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even image, and began making plans for The Large Glass – scribbling short notes to himself, sometimes with hurried sketches. It would be more than ten years before this piece was completed. Not much else is known about the two-month stay in Munich except that the friend he visited was intent on showing him the sights and the nightlife, and that he was influenced by the works of the sixteenth century German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder in Munich's famed Alte Pinakothek, known for its Old Master paintings. Duchamp recalled that he took the short walk to visit this museum daily. Duchamp scholars have long recognized in Cranach the subdued ochre and brown color range Duchamp later employed.[25]

The same year, Duchamp also attended a performance of a stage adaptation of Raymond Roussel's 1910 novel, Impressions d'Afrique, which featured plots that turned in on themselves, word play, surrealistic sets and humanoid machines. He credited the drama with having radically changed his approach to art, and having inspired him to begin the creation of his The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, also known as The Large Glass. Work on The Large Glass continued into 1913, with his invention of inventing a repertoire of forms. He made notes, sketches and painted studies, and even drew some of his ideas on the wall of his apartment.

Toward the end of 1912, he traveled with Picabia, Apollinaire and Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia through the Jura mountains, an adventure that Buffet-Picabia described as one of their "forays of demoralization, which were also forays of witticism and clownery ... the disintegration of the concept of art".[26] Duchamp's notes from the trip avoid logic and sense, and have a surrealistic, mythical connotation.

Duchamp painted few canvases after 1912, and in those he did, he attempted to remove "painterly" effects, and to use a technical drawing approach instead.

His broad interests led him to an exhibition of aviation technology during this period, after which Duchamp said to his friend Constantin Brâncuși, "Painting is washed up. Who will ever do anything better than that propeller? Tell me, can you do that?".[26] Brâncuși later sculpted bird forms. U.S. Customs officials mistook them for aviation parts and attempted to collect import duties on them.

In 1913, Duchamp withdrew from painting circles and began working as a librarian in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève to be able to earn a living wage while concentrating on scholarly realms and working on his Large Glass. He studied math and physics – areas where exciting new discoveries were taking place. The theoretical writings of Henri Poincaré particularly intrigued and inspired Duchamp. Poincaré postulated that the laws believed to govern matter were created solely by the minds that "understood" them and that no theory could be considered "true". "The things themselves are not what science can reach..., but only the relations between things. Outside of these relations there is no knowable reality", Poincaré wrote in 1902.[27] Reflecting the influence of Poincaré's writings, Duchamp tolerated any interpretation of his art by regarding it as the creation of the person who formulated it, not as truth.[28]

Duchamp's own art-science experiments began during his tenure at the library. To make one of his favorite pieces, 3 Standard Stoppages (3 stoppages étalon), he dropped three 1-meter lengths of thread onto prepared canvases, one at a time, from a height of 1 meter. The threads landed in three random undulating positions. He varnished them into place on the blue-black canvas strips and attached them to glass. He then cut three wood slats into the shapes of the curved strings, and put all the pieces into a croquet box. Three small leather signs with the title printed in gold were glued to the "stoppage" backgrounds. The piece appears to literally follow Poincaré's School of the Thread, part of a book on classical mechanics.

In his studio he mounted a bicycle wheel upside down onto a stool, spinning it occasionally just to watch it. Although it is often assumed that the Bicycle Wheel represents the first of Duchamp's "Readymades", this particular installation was never submitted for any art exhibition, and it was eventually lost. However, initially, the wheel was simply placed in the studio to create atmosphere: "I enjoyed looking at it just as I enjoy looking at the flames dancing in a fireplace."[29]

After World War I started in August 1914, with his brothers and many friends in military service and himself exempted (due to a heart murmur),[30][31] Duchamp felt uncomfortable in Paris. Meanwhile, Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 had scandalized Americans at the Armory Show, and helped secure the sale of all four of his paintings in the exhibition. Thus, being able to finance the trip, Duchamp decided to emigrate to the United States in 1915. To his surprise, he found he was a celebrity when he arrived in New York in 1915, where he quickly befriended art patron Katherine Dreier and artist Man Ray. Duchamp's circle included art patrons Louise and Walter Conrad Arensberg, actress and artist Beatrice Wood and Francis Picabia, as well as other avant-garde figures. Though he spoke little English, in the course of supporting himself by giving French lessons, and through some library work, he quickly learned the language. Duchamp became part of an artist colony in Ridgefield, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City.[32]

For two years the Arensbergs, who would remain his friends and patrons for 42 years, were the landlords of his studio. In lieu of rent, they agreed that his payment would be The Large Glass. An art gallery offered Duchamp $10,000 per year in exchange for all of his yearly production, but he declined the offer, preferring to continue his work on The Large Glass.

Société Anonyme

editDuchamp created the Société Anonyme in 1920, along with Katherine Dreier and Man Ray. This was the beginning of his lifelong involvement in art dealing and collecting. The group collected modern art works, and arranged modern art exhibitions and lectures throughout the 1930s.

By this time Walter Pach, one of the coordinators of the 1913 Armory Show, sought Duchamp's advice on modern art. Beginning with Société Anonyme, Dreier also depended on Duchamp's counsel in gathering her collection, as did Arensberg. Later Peggy Guggenheim, Museum of Modern Art directors Alfred Barr and James Johnson Sweeney consulted with Duchamp on their modern art collections and shows.

Dada

editDada or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century. It began in Zürich, Switzerland, in 1916, and spread to Berlin shortly thereafter.[33] To quote Dona Budd's The Language of Art Knowledge,

Dada was born out of negative reaction to the horrors of World War I. This international movement was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich. Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality, and intuition. The origin of the name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsense word. Others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco's frequent use of the words da, da, meaning yes, yes in the Romanian language. Another theory says that the name "Dada" came during a meeting of the group when a paper knife stuck into a French-German dictionary happened to point to "dada", a French word for "hobbyhorse".[34]

The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature, poetry, art manifestoes, art theory, theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works. In addition to being anti-war, Dada was also anti-bourgeois and had political affinities with the radical left.

Dada activities included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media. Key figures in the movement, apart from Duchamp, included: Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Johannes Baader, Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Richard Huelsenbeck, Georg Grosz, John Heartfield, Beatrice Wood, Kurt Schwitters, and Hans Richter, among others. The movement influenced later styles, such as the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism, Nouveau réalisme, pop art, and Fluxus.

Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of antiart to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that lay the foundation for Surrealism.[35]

New York Dada had a less serious tone than that of European Dadaism, and was not a particularly organized venture. Duchamp's friend Francis Picabia connected with the Dada group in Zürich, bringing to New York the Dadaist ideas of absurdity and "anti-art". Duchamp and Picabia first met in September 1911 at the Salon d'Automne in Paris, where they were both exhibiting. Duchamp showed a larger version of his Young Man and Girl in Spring 1911, a work that had an Edenic theme and a thinly veiled sexuality also found in Picabia's contemporaneous Adam and Eve 1911. According to Duchamp, "our friendship began right there".[36] A group met almost nightly at the Arensberg home, or caroused in Greenwich Village. Together with Man Ray, Duchamp contributed his ideas and humor to the New York activities, many of which ran concurrent with the development of his Readymades and The Large Glass.

The most prominent example of Duchamp's association with Dada was his submission of Fountain, a urinal, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibit in 1917. Artworks in the Independent Artists shows were not selected by jury, and all pieces submitted were displayed. However, the show committee insisted that Fountain was not art, and rejected it from the show. This caused an uproar among the Dadaists, and led Duchamp to resign from the board of the Independent Artists.[37]: 181–186

Along with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, Duchamp published multiple Dada magazines in New York—including The Blind Man and Rongwrong—which included art, literature, humor and commentary.

When he returned to Paris after World War I, Duchamp did not participate in the Dada group.

Readymades

edit"Readymades" were found objects which Duchamp chose and presented as art. In 1913, Duchamp installed a Bicycle Wheel in his studio. The Bicycle Wheel was an idea of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. However, the idea of Readymades did not fully develop until 1915. The idea was to question the very notion of Art, and the adoration of art, which Duchamp found "unnecessary".[38]

My idea was to choose an object that wouldn't attract me, either by its beauty or by its ugliness. To find a point of indifference in my looking at it, you see.[38]

Bottle Rack (1914), a bottle-drying rack signed by Duchamp, is considered to be the first "pure" readymade. In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915), a snow shovel, also called Prelude to a Broken Arm, followed soon after. His Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym "R. Mutt", shocked the art world in 1917.[31] Fountain was selected in 2004 as "the most influential artwork of the 20th century" by 500 renowned artists and historians.[8]

In 1919, Duchamp made a parody of the Mona Lisa by adorning a cheap reproduction of the painting with a mustache and goatee. To this he added the inscription L.H.O.O.Q., a phonetic game which, when read out loud in French quickly sounds like "Elle a chaud au cul". This can be translated as "She has a hot ass", implying that the woman in the painting is in a state of sexual excitement and availability. It may also have been intended as a Freudian joke, referring to Leonardo da Vinci's alleged homosexuality. Duchamp gave a "loose" translation of L.H.O.O.Q. as "there is fire down below" in a late interview with Arturo Schwarz. According to Rhonda Roland Shearer, the apparent Mona Lisa reproduction is in fact a copy modeled partly on Duchamp's own face.[40] Research published by Shearer also speculates that Duchamp himself may have created some of the objects which he claimed to be "found objects".

Antecedent

editIn 2017-2018, the French expert Johann Naldi found and identified seventeen unpublished works in a private collection, classified as a national treasure on May 7, 2021 by the French Ministry of Culture, including Des souteneurs encore dans la force de l'âge et le ventre dans l'herbe by Alphonse Allais, consisting of a green carriage curtain suspended from a wooden cylinder.[41] This work was certainly exhibited at the Incoherents exhibitions in Paris between 1883 and 1893. According to Johann Naldi, this work is the oldest known readymade and was a source of inspiration for Marcel Duchamp.[42]

The Large Glass

editDuchamp worked on his complex Futurism-inspired piece The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) from 1915 to 1923, except for periods in Buenos Aires and Paris in 1918–1920. He executed the work on two panes of glass with materials such as lead foil, fuse wire, and dust. It combines chance procedures, plotted perspective studies, and laborious craftsmanship. He published notes for the piece, The Green Box, intended to complement the visual experience. They reflect the creation of unique rules of physics, and a mythology which describes the work. He stated that his "hilarious picture" is intended to depict the erotic encounter between a bride and her nine bachelors.

A performance of the stage adaptation of Raymond Roussel's novel Impressions d'Afrique, which Duchamp attended in 1912, inspired the piece. Notes, sketches and plans for the work were drawn on his studio walls as early as 1913. To concentrate on the work free from material obligations, Duchamp found work as a librarian while living in France. After immigrating to the United States in 1915, he began work on the piece, financed by the support of the Arensbergs.

The piece is partly constructed as a retrospective of Duchamp's works, including a three-dimensional reproduction of his earlier paintings Bride (1912), Chocolate Grinder (1914) and Glider containing a water mill in neighboring metals (1913–1915), which has led to numerous interpretations. The work was formally declared "Unfinished" in 1923. Returning from its first public exhibition in a shipping crate, the glass suffered a large crack. Duchamp repaired it, but left the smaller cracks in the glass intact, accepting the chance element as a part of the piece.

Joseph Nechvatal has cast a considerable light on The Large Glass by noting the autoerotic implications of both bachelorhood and the repetitive, frenetic machine; he then discerns a larger constellation of themes by insinuating that autoeroticsm – and with the machine as omnipresent partner and practitioner – opens out into a subversive pan-sexuality as expressed elsewhere in Duchamp's work and career, in that a trance-inducing pleasure becomes the operative principle as opposed to the dictates of the traditional male-female coupling; and he as well documents the existence of this theme cluster throughout modernism, starting with Rodin's controversial Monument to Balzac, and culminating in a Duchampian vision of a techno-universe in which one and all can find themselves welcomed.[43]

Until 1969 when the Philadelphia Museum of Art revealed Duchamp's Étant donnés tableau, The Large Glass was thought to have been his last major work.

Kinetic works

editDuchamp's interest in kinetic art works can be discerned as early as the notes for The Large Glass and the Bicycle Wheel readymade, and despite losing interest in "retinal art", he retained interest in visual phenomena. In 1920, with help from Man Ray, Duchamp built a motorized sculpture, Rotative plaques verre, optique de précision ("Rotary Glass Plates, Precision Optics"). The piece, which he did not consider to be art, involved a motor to spin pieces of rectangular glass on which were painted segments of a circle. When the apparatus spins, an optical illusion occurs, where the segments appear to be closed concentric circles. Man Ray set up equipment to photograph the initial experiment, but when they turned the machine for the second time, a drive belt broke and caught a piece of the glass, which after glancing off Man Ray's head, shattered into bits.[37]: 227–228

After moving back to Paris in 1923, at André Breton's urging, with financing by Jacques Doucet, Duchamp built another optical device based on the first one, Rotative Demisphère, optique de précision (Rotary Demisphere, Precision Optics). This time the optical element was a globe cut in half, with black concentric circles painted on it. When it spins, the circles appear to move backward and forward in space. Duchamp asked that Doucet not exhibit the apparatus as art.[37]: 254–255

Rotoreliefs were the next phase of Duchamp's spinning works. To make the optical "play toys", he painted designs on flat cardboard circles and spun them on a phonographic turntable. When spinning, the flat disks appeared three-dimensional. He had a printer produce 500 sets of six of the designs, and set up a booth at a 1935 Paris inventors' show to sell them. The venture was a financial disaster, but some optical scientists thought they might be of use in restoring three-dimensional stereoscopic sight to people who have lost vision in one eye.[37]: 301–303 In collaboration with Man Ray and Marc Allégret, Duchamp filmed early versions of the Rotoreliefs, and they named the film Anémic Cinéma (1926). Later, in Alexander Calder's studio in 1931, while looking at the sculptor's kinetic works, Duchamp suggested that these should be called mobiles. Calder agreed to use this novel term in his upcoming show. To this day, sculptures of this type are called "mobiles".[37]: 294

Musical ideas

editBetween 1912 and 1915, Duchamp worked with various musical ideas. At least three pieces have survived: two compositions and a note for a musical happening. The two compositions are based on chance operations. Erratum Musical, written for three voices, was published in 1934. La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même. Erratum Musical is unfinished and was never published or exhibited during Duchamp's lifetime. According to the manuscript, the piece was intended for a mechanical instrument "in which the virtuoso intermediary is suppressed". The manuscript also contains a description for "An apparatus automatically recording fragmented musical periods," consisting of a funnel, several open-end cars and a set of numbered balls.[44] These pieces predate John Cage's Music of Changes (1951), which is often considered the first modern piece to be conceived largely through random procedures.[45]

In 1968, Duchamp and John Cage appeared together at a concert entitled "Reunion", playing a game of chess and composing Aleatoric music by triggering a series of photoelectric cells underneath the chessboard.[46]

Rrose Sélavy

edit"Rrose Sélavy", also spelled Rose Sélavy, was one of Duchamp's pseudonyms. The name, a pun, sounds like the French phrase Eros, c'est la vie, which may be translated as "Eros, such is life." It has also been read as arroser la vie ("to make a toast to life"). Sélavy emerged in 1921 in a series of photographs by Man Ray showing Duchamp dressed as a woman. Through the 1920s Man Ray and Duchamp collaborated on more photos of Sélavy. Duchamp later used the name as the byline on written material and signed several creations with it.

Duchamp used the name in the title of at least one sculpture, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? (1921). The sculpture, a type of readymade called an assemblage, consists of an oral thermometer, a couple of dozen small cubes of marble resembling sugar cubes and a cuttlefish bone inside a birdcage. Sélavy also appears on the label of Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (1921), a readymade that is a perfume bottle in the original box. Duchamp also signed his film Anémic Cinéma (1926) with the Sélavy name.

The inspiration for the name Rrose Sélavy has been thought to be Belle da Costa Greene, J. P. Morgan's librarian at The Morgan Library & Museum (formerly The Pierpont Morgan Library) who, following his death, became the Library's director, working there for a total of forty-three years. Empowered by J. P. Morgan, and then by his son Jack, Greene built the collection buying and selling rare manuscripts, books and art.[47]

Rrose Sélavy, and the other pseudonyms Duchamp used, may be read as a comment on the fallacy of romanticizing the conscious individuality or subjectivity of the artist, a theme that is also a prominent subtext of the readymades. Duchamp said in an interview, "You think you're doing something entirely your own, and a year later you look at it and you see actually the roots of where your art comes from without your knowing it at all."[48] The Pérez Art Museum Miami, in Florida, holds the piece Boîte-en-valise (De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy), or in English, Box in a Valise (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy) created from 1941-61, in the museum's collection.[49]

From 1922, the name Rrose Sélavy also started appearing in a series of aphorisms, puns, and spoonerisms by the French surrealist poet Robert Desnos. Desnos tried to portray Rrose Sélavy as a long-lost aristocrat and rightful queen of France. Aphorism 13 paid homage to Marcel Duchamp: Rrose Sélavy connaît bien le marchand du sel ‒ in English: "Rrose Sélavy knows the merchant of salt well"; in French the final words sound like Mar-champ Du-cel. Note that the "salt seller" aphorism – "mar-chand-du-sel" – is a phonetic anagram of the artist's name: "mar-cel-du-champ". (Duchamp's compiled notes are entitled, "Salt Seller".) In 1939 a collection of these aphorisms was published under the name of Rrose Sélavy, entitled, Poils et coups de pieds en tous genres.

Transition from art to chess

editIn 1918, Duchamp took leave of the New York art scene, interrupting his work on the Large Glass, and went to Buenos Aires, where he remained for nine months and often played chess. He carved his own chess set from wood with help from a local craftsman who made the knights. He moved to Paris in 1919, and then back to the United States in 1920. Upon his return to Paris in 1923, Duchamp was, in essence, no longer a practicing artist. Instead, his main interest was chess, which he studied for the rest of his life to the exclusion of most other activities.

Duchamp is seen, briefly, playing chess with Man Ray in the short film Entr'acte (1924) by René Clair. He designed the 1925 poster for the Third French Chess Championship, and as a competitor in the event, finished at fifty percent (3–3, with two draws), earning the title of chess master. During this period his fascination with chess so distressed his first wife that she glued his pieces to the chessboard. Duchamp continued to play in the French Championships and in the Chess Olympiads from 1928 to 1933, favoring hypermodern openings such as the Nimzo-Indian.

Sometime in the early 1930s, Duchamp reached the height of his ability, but realized that he had little chance of winning recognition in top-level chess. In the following years, his participation in chess tournaments declined, but he discovered correspondence chess and became a chess journalist, writing weekly newspaper columns. While his contemporaries were achieving spectacular success in the art world by selling their works to high-society collectors, Duchamp observed, "I am still a victim of chess. It has all the beauty of art—and much more. It cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position."[50] On another occasion, Duchamp elaborated, "The chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chess-board, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem. ... I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists."[51]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In 1932, Duchamp teamed with chess theorist Vitaly Halberstadt to publish L'opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled), known as corresponding squares. This treatise describes the Lasker-Reichhelm position, an extremely rare type of position that can arise in the endgame. Using enneagram-like charts that fold upon themselves, the authors demonstrated that in this position, the most Black can hope for is a draw.

The theme of the "endgame" is important to an understanding of Duchamp's complex attitude toward his artistic career. Irish playwright Samuel Beckett was an associate of Duchamp, and used the theme as the narrative device for the 1957 play of the same name, Endgame. In 1968, Duchamp played an artistically important chess match with avant-garde composer John Cage, at a concert entitled "Reunion". Music was produced by a series of photoelectric cells underneath the chessboard, triggered sporadically by normal game play.[46]

On choosing a career in chess, Duchamp said, "If Bobby Fischer came to me for advice, I certainly would not discourage him—as if anyone could—but I would try to make it positively clear that he will never have any money from chess, live a monk-like existence and know more rejection than any artist ever has, struggling to be known and accepted."[53]

Duchamp left a legacy to chess in the form of an enigmatic endgame problem he composed in 1943. The problem was included in the announcement for Julian Levi's gallery exhibition Through the Big End of the Opera Glass, printed on translucent paper with the faint inscription: "White to play and win". Grandmasters and endgame specialists have since grappled with the problem, with most concluding that there is no solution.[54]

Later artistic involvement

editAlthough Duchamp was no longer considered to be an active artist, he continued to consult with artists, art dealers and collectors. From 1925 he often traveled between France and the United States, and made New York's Greenwich Village his home in 1942. He also occasionally worked on artistic projects such as the short film Anémic Cinéma (1926), Box in a Valise (1935–1941), Self Portrait in Profile (1958) and the larger work Étant Donnés (1946–1966). In 1943, he participated with Maya Deren in her unfinished film The Witch's Cradle, filmed in Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery.

From the mid-1930s onward he collaborated with the Surrealists; however, he did not join the movement, despite the coaxing of André Breton. From then until 1944, together with Max Ernst, Eugenio Granell, and Breton, Duchamp edited the Surrealist periodical VVV, and served as an advisory editor for the magazine View, which featured him in its March 1945 edition, thus introducing him to a broader American audience.

Duchamp's influence on the art world remained behind the scenes until the late 1950s, when he was "discovered" by young artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, who were eager to escape the dominance of Abstract Expressionism. He was a co-founder of the international literary group Oulipo in 1960. Interest in Duchamp was reignited in the 1960s, and he gained international public recognition. In 1963, the Pasadena Art Museum mounted his first retrospective exhibition, and there he appeared in an iconic photograph playing chess opposite nude model Eve Babitz, photographed by Julian Wasser.[55][56] The photograph was later described by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art as being "among the key documentary images of American modern art".[57]

The Tate Gallery hosted a large exhibit of his work in 1966. Other major institutions, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, followed with large showings of Duchamp's work. He was invited to lecture on art and to participate in formal discussions, as well as sitting for interviews with major publications. As the last surviving member of the Duchamp family of artists, in 1967 Duchamp helped to organize an exhibition in Rouen, France, called Les Duchamp: Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Marcel Duchamp, Suzanne Duchamp. Parts of this family exhibition were later shown again at the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris.

Exhibition design and installation art

editDuchamp participated in the design of the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, held at the Galerie des Beaux-arts, Paris. The show was organised by André Breton and Paul Éluard, and featured "Two hundred and twenty-nine artworks by sixty exhibitors from fourteen countries... at this multimedia exhibition."[58] The Surrealists wanted to create an exhibition which in itself would be a creative act, thus working collaboratively in its staging. Marcel Duchamp was named as "Generateur-arbitre", Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst were listed as technical directors, Man Ray was chief lighting technician and Wolfgang Paalen responsible for "water and foliage".[59]

Plus belles rues de Paris (The most beautiful streets of Paris) filled one side of the lobby with mannequins dressed by various Surrealists.[58] The main hall, or the Salle de Superstition (Room of Superstition), was "a cave-like Gesamtkunstwerk" notably including Duchamp's installation, Twelve Hundred Coal Bags Suspended from the Ceiling over a Stove, which was literally 1,200 stuffed coal bags suspended from the ceiling.[60][61] The floor was covered by Paalen with dead leaves and mud from the Montparnasse Cemetery. In the middle of the grand hall underneath Duchamp's coal sacks, Paalen installed an artificial water-filled pond with real water lilies and reeds, which he called Avant La Mare. A single light bulb provided the only illumination,[62] so patrons were given flashlights with which to view the art (an idea of Man Ray), while the aroma of roasting coffee filled the air. Around midnight, the visitors witnessed the dancing shimmer of a scantily dressed girl who suddenly arose from the reeds, jumped on a bed, shrieked hysterically, then disappeared just as quickly. Much to the Surrealists' satisfaction, the exhibition scandalized many of the guests.

In 1942, for the First Papers of Surrealism show in New York, surrealists called on Duchamp to design the exhibition. He created an installation, His Twine, commonly known as the "mile of string", it was a three-dimensional web of string throughout the rooms of the space, in some cases making it almost impossible to see the works.[61][63] Duchamp made a secret arrangement with an associate's son to bring young friends to the opening of the show. When the formally-dressed patrons arrived, they found a dozen children in athletic clothes kicking and passing balls, and skipping rope. When questioned, the children were told to say "Mr. Duchamp told us we could play here". Duchamp's design of the catalog for the show included "found", rather than posed, photographs of the artists.

Breton with Duchamp organized the exhibition "Le surréalisme en 1947" in the Galerie Maeght in Paris after the war and named set designer Frederick Kiesler as architect.[60]

Étant donnés

editDuchamp's final major art work surprised the art world, which believed he had given up art for chess 25 years earlier. Entitled Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage ("Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas"), it is a tableau, visible only through a peep hole in a wooden door.[64] A nude woman may be seen lying on her back with her face hidden, legs spread, and one hand holding a gas lamp in the air against a landscape backdrop.[65] Duchamp had worked secretly on the piece from 1946 to 1966 in his Greenwich Village studio while even his closest friends thought he had abandoned art. The torso of the nude figure is based on Duchamp's lover, the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins, with whom he had an affair from 1946 to 1951.[66]

Personal life

editThroughout his adult life, Duchamp was a passionate smoker of Habana cigars.[67]

Duchamp became a United States citizen in 1955.[68]

In June 1927, Duchamp married Lydie Sarazin-Levassor; however, they divorced six months later. It was rumored that Duchamp had chosen a marriage of convenience, because Sarazin-Levassor was the daughter of a wealthy automobile manufacturer. Early in January 1928, Duchamp said that he could no longer bear the responsibility and confinement of marriage, and they were soon divorced.[69]

Between 1946 and 1951 Maria Martins was his mistress.[70]

In 1954, he and Alexina "Teeny" Sattler married. They remained together until his death.

Duchamp was an atheist.[71]

Death and burial

editDuchamp died suddenly and peacefully in the early morning of 2 October 1968 at his home in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. After an evening dining at home with his friends Man Ray and Robert Lebel, Duchamp retired at 1:05 am, collapsed in his studio, and died of heart failure.[72]

He is buried in the Rouen Cemetery, in Rouen, France, with the epitaph, "D'ailleurs, c'est toujours les autres qui meurent" ("Besides, it's always the others who die").

Legacy

editMany critics consider Duchamp to be one of the most important artists of the 20th century,[73][74][75][76][77] and his output influenced the development of post–World War I Western art. He advised modern art collectors, such as Peggy Guggenheim and other prominent figures, thereby helping to shape the tastes of Western art during this period.[37] He challenged conventional thought about artistic processes and rejected the emerging art market, through subversive anti-art.[78] He famously dubbed a urinal art and named it Fountain. Duchamp produced relatively few artworks and remained mostly aloof of the avant-garde circles of his time. He went on to pretend to abandon art and devote the rest of his life to chess, while secretly continuing to make art.[79] In 1958 Duchamp said of creativity,

The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.[80]

Duchamp in his later life explicitly expressed negativity toward art. In a BBC interview with Duchamp conducted by Joan Bakewell in 1968 he compared art with religion, saying that he wished to do away with art the same way many have done away with religion. Duchamp goes on to explain to the interviewer that "the word art etymologically means to do", that art means activity of any kind, and that it is our society that creates "purely artificial" distinctions of being an artist.[81][82]

A quotation erroneously attributed to Duchamp suggests a negative attitude toward later trends in 20th century art:

This Neo-Dada, which they call New Realism, Pop Art, Assemblage, etc., is an easy way out, and lives on what Dada did. When I discovered the ready-mades I sought to discourage aesthetics. In Neo-Dada they have taken my readymades and found aesthetic beauty in them, I threw the bottle-rack and the urinal into their faces as a challenge and now they admire them for their aesthetic beauty.

However, this was written in 1961 by fellow Dadaist Hans Richter, in the second person, i.e. "You threw the bottle-rack...". Although a marginal note in the letter suggests that Duchamp generally approved of the statement, Richter did not make the distinction clear until many years later.[83]

Duchamp's attitude was more favorable, however, as evidenced by another statement made in 1964:

Pop Art is a return to "conceptual" painting, virtually abandoned, except by the Surrealists, since [Gustave] Courbet, in favor of retinal painting... If you take a Campbell soup can and repeat it 50 times, you are not interested in the retinal image. What interests you is the concept that wants to put 50 Campbell soup cans on a canvas.[84]

The Prix Marcel Duchamp (Marcel Duchamp Prize), established in 2000, is an annual award given to a young artist by the Centre Georges Pompidou. In 2004, as a testimony to the legacy of Duchamp's work to the art world, a panel of prominent artists and art historians voted Fountain "the most influential artwork of the 20th century".[8][85]

Art market

editOn 17 November 1999, a version of Fountain (owned by Arturo Schwarz) was sold at Sotheby's, New York, for $1,762,500 to Dimitris Daskalopoulos, who declared that Fountain represented the origin of contemporary art.[86] The price set a world record, at the time, for a work by Marcel Duchamp at public auction.[87][88] The record has since been surpassed by a work sold at Christie's Paris, titled Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (1921). The readymade of a perfume bottle in its box sold for a record $11.5 million (€8.9 million).[89]

Selected works

edit-

Marcel Duchamp, 1910, Joueur d'échecs (The Chess Game), oil on canvas, 114 x 146.5 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Marcel Duchamp, 1911, Coffee Mill (Moulin à café), oil and graphite on board, 33 x 12.7 cm, Tate, London. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme"

-

Marcel Duchamp, 1911, La sonate (Sonata), oil on canvas, 145.1 x 113.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Exhibited at Exposició d'Art Cubista, Barcelona, Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona, 1912 (reproduced in catalogue)

-

Marcel Duchamp, 1912, Le Roi et la Reine entourés de Nus vites (The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes), oil on canvas, 114.6 x 128.9 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, in the Frederick C. Torrey home, c. 1913

See also

edit- Shock art

- Stereokinetic stimulus

- Fourth dimension in art

- Fountain Archive

- Transatlantic (portrayal in 2023 TV series)

Notes

edit- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). "Duchamp". Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Ian Chilvers & John Glaves-Smith, A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press, p. 203

- ^ "Francis M. Naumann, Marcel Duchamp, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, MoMA, 2009". Moma.org. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp". TheArtStory.org. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "Tate Modern: Matisse Picasso". Tate Etc. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Searle, Adrian (7 May 2002). "A momentous, tremendous exhibition". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Trachtman, Paul (February 2003). "Matisse & Picasso". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 8 May 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ a b c "Duchamp's urinal tops art survey". BBC News. 1 December 2004. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013. Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) at Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Guy Pessiot, Histoire de Rouen volume 2 1900–1939 en 800 photographies Archived 22 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, repr. Rouen: PTC, 2004, ISBN 9782906258877, p. 271 (in French)

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp, 1911–12, Nude (Study), Sad Young Man on a Train, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice". Guggenheim.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ theartstory.org Archived 27 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (fr)Victoria Charles, Joseph Manca, Megan McShane, 1000 Chefs-d'œuvre de la peinture

- ^ François Lespinasse, Robert Antoine Pinchon: 1886–1943, 1990, repr. Rouen: Association les amis de l'École de Rouen, 2007, ISBN 9782906130036 (in French)

- ^ Pierre Lartigue, Rose Sélavy et caetera, University of Michigan, Le Passage, 2004, p. 65, ISBN 2847420436

- ^ Judith Housez, Marcel Duchamp: biographie, Grasset, 2006, p. 93, ISBN 2246630819

- ^ Bernard Marcadé, Marcel Duchamp: la vie à crédit : biographie, Flammarion, 2007, p. 28, ISBN 2080682261

- ^ Ian Chilvers & John Glaves-Smith, A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press, p. 204

- ^ Cabanne, 1971 p.29.

- ^ Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors, New York 1962, pp.31–2

- ^ a b c d Peter Brooke, The "rejection" of Nude Descending a Staircase Archived 9 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tomkins 1996, p. 83

- ^ William H. Robinson, Jordi Falgàs, Carmen Belen Lord, Barcelona and Modernity: Picasso, Gaudí, Miró, Dalí, Cleveland Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0300121067

- ^ Tomkins 1996, p. unknown

- ^ Naumann, Francis M. (6 November 2012). "Marcel Duchamp Slept Here". The Brooklyn Rail. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ a b Mink, J. (2004). Duchamp. Taschen.

- ^ Poincaré, H. (1902) Science and Hypothesis. London: Walter Scott Publishing Co., p. xxiv.

- ^ Mink, J. (2000). Marcel Duchamp. Art as Anti-Art. Taschen Verlag.

- ^ Mink, J. (2004) Duchamp. Taschen, p. 48.

- ^ Paul B. Franklin, The Artist and His Critic Stripped Bare: The Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp and Robert Lebel Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Getty Publications, 1 June 2016, ISBN 1606064436

- ^ a b Cabanne, P., & Duchamp, M. (1971). Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. New York: Viking Press. Hachette UK, 21 July 2009

- ^ "Icons of twentieth century photography come to Edinburgh for major Man Ray exhibition", ArtDaily. Retrieved 15 December 2013. "In 1915, whilst at Ridgefield artist colony in New Jersey, he [Man Ray] met the French artist Marcel Duchamp and together they tried to establish a New York outpost of the Dada movement."

- ^ de Micheli, Mario (2006). Las vanguardias artísticas del siglo XX. Alianza Forma. pp. 135–137

- ^ Budd, Dona, The Language of Art Knowledge, Pomegranate Communications, Inc.

- ^ Marc Lowenthal, translator's introduction to Francis Picabia's I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, and Provocation

- ^ Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia; Edited by Jennifer Mundy; TATE 2008; p. 12

- ^ a b c d e f Tomkins: Duchamp: A Biography.

- ^ a b Interview, BBC TV, Joan Bakewell, 1966

- ^ Marcel Duchamp 1887–1968, dadart.com

- ^ Marting, Marco De (2003). "Mona Lisa: Who is Hidden Behind the Woman with the Mustache?". Art Science Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Philippe, Dagen (10 May 2021). "Dix-neuf œuvres des Arts incohérents classées trésor national". Le Monde.

- ^ Johann, Naldi (April 2022). Arts incohérents, Discoveries and new perspectives. Paris: Lienart. ISBN 978-2-35906-368-4.

- ^ Joseph Nechvatal (18 October 2018). "Before and Beyond the Bachelor Machine". Arts. 7 (4): 67. doi:10.3390/arts7040067.

- ^ Petr Kotik. Liner Notes to CD "The Music of Marcel Duchamp", Edition Block + Paula Cooper Gallery, 1991.

- ^ Randel, Don Michael. 2002. The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians. ISBN 0-674-00978-9.

- ^ a b ""Becoming Duchamp" by Sylvère Lotringer". Toutfait.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Duchamp Bottles Belle Greene: Just Desserts For His Canning Archived 27 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine by Bonnie Jean Garner.

- ^ Tomkins, Calvin (2013). Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews. New York, NY: ARTBOOK | D.A.P. p. 49. ISBN 978-1936440399.

- ^ "Boîte-en-valise (De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy) (Box in a Valise (From or by Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy)) • Pérez Art Museum Miami". Pérez Art Museum Miami. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Time Magazine. 10 March 1952

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp." Kynaston McShine.1989.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp's Problem - Chess Forums". Chess.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Brady, Frank: Bobby Fischer: profile of a prodigy, Courier Dover Publications, 1989; p. 207.

- ^ Beliavsky, A & Mikhalchishin, A., Winning Endgame Technique, Batsford, 1995.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (9 February 2023). "Julian Wasser, Famed L.A. Photojournalist, Dies at 89". LAmag. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Anolik, Lili (March 2014). "All About Eve—and Then Some". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Karlstrom, Paul. "Oral history interview with Eve Babitz, 2000 Jun 14". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Behind The Scenes of the Legendary International Surrealist Exhibition | Widewalls". www.widewalls.ch. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Jubiläums-Ausstellung Mannheim 1907: Internationale Kunst- und Grosse Gartenbau-Ausstellung, vom 1. Mai bis 20. Oktober : offizieller Katalog der Gartenbau-Ausstellung /. Mannheim: Internationale Kunst- und Grosse Gartenbau-Ausstellung. 1907. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.118599.

- ^ a b "NYAB Event - "Display of the Centuries. Frederick Kiesler and Contemporary Art" Exhibition". www.nyartbeat.com. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ a b Tate. "Duchamp, Childhood, Work and Play: The Vernissage for First Papers of Surrealism, New York, 1942 – Tate Papers". Tate. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp". Toutfait.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp". Toutfait.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Tourfait Notes: Exterior view". Toutfait.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Tourfait Notes: Interior view". Toutfait.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Cotter, Holland. "Duchamp in Philadelphia – Peepholes Onto a Landscape of Eros", The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ door K-films (5 July 2010). "see him on film". Dailymotion.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp". Guggenheim. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Hulten, Pontus. Marcel Duchamp, Work and Life: Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Selavy, 1887–1968. Pages 8–9 June (1927) to 25 January (1928). ISBN 0-262-08225-X.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (27 August 2009). "Landscape of Eros, Through the Peephole". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. Da Capo Press. 21 July 2009. p. 106. ISBN 9780786749713.

Cabanne: "Do you believe in God?" Duchamp: "No, not at all."

- ^ Kuenzli, Rudolf E.; Naumann, Francis M. (1991). Rudolf Ernst Kuenzli, Francis M. Naumann, essay by Arturo Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, Issue 16 of Dada surrealism, MIT Press, 1991, ISBN 0262610728. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262610728. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Tomkins, Calvin (15 March 1998). Duchamp:A biography. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0805057897.

Regarded by many in the art world as the most influential artist of the century

- ^ "Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit. – Review – book review" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Making Sense of Marcel Duchamp". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Duchamp & Androgyny: The Concept and its Context". Archived from the original on 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Marcel Duchamp: The Bachelor Stripped Bare". Archived from the original on 9 August 2011.

- ^ Tomkins, 1966, p.38-39

- ^ Ian Chilvers & John Glaves-Smith, A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press, p. 205

- ^ Marcel Duchamp, from Session on the Creative Act, Convention of the American Federation of Arts, Houston, Texas, April 1957.

- ^ "Joan Bakewell in conversation with Marcel Duchamp". BBC Arts. 1968. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Kuenzli, Rudolf Ernst; Naumann, Francis M (1990). Marcel Duchamp. MIT Press. p. 234. ISBN 9780262610728.

bbc 1966 interview duchamp joan bakewell.

- ^ "(Ab)Using Marcel Duchamp: The Concept of the Readymade in Post-War and Contemporary American Art" Archived 7 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine by Thomas Girst at toutfait.com, Issue 5, 2003.

- ^ Rosalind Constable, "New York's Avant-garde, and How It Got There", New York Herald Tribune, May 17, 1964, p. 10, cited in Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, "Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy, 1887–1968", in Pontus Hulten, ed., Marcel Duchamp, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1993, entry for May 17, 1964. See also Campbell's Soup Cans#Interpretation.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte; correspondent, arts (2 December 2004). "Work of art that inspired a movement ... a urinal". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

{{cite news}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ Vogel, Carol (18 November 1999). "More Records for Contemporary Art". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Francis M. Naumann, "The Art Defying the Art Market", Tout-fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal, vol. 2, 5, April 2003

- ^ Carter B. Horsley, Contemporary Art & 14 Duchamp Readymades, The City Review, 2002

- ^ Laurie Hurwitz, Saint Laurent Collection Soars at Christie's Paris. Duchamp's Belle haleine–Eau de voilette, 1921

References

edit- Tomkins, Calvin (1996). Duchamp: A Biography. Henry Holt and Company, Inc. ISBN 0-8050-5789-7.

- Tomkins, Calvin: Duchamp: The World of Marcel Duchamp 1887–, Time Inc., 1966. ISBN 158334148X

- Ian Chilvers & John Glaves-Smith: A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press, pp. 202–205

- Seigel, Jerrold: The Private Worlds of Marcel Duchamp, University of California Press, 1995. ISBN 0-520-20038-1

- Hulten, Pontus (editor): Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life, The MIT Press, 1993. ISBN 0-262-08225-X

- Yves Arman: Marcel Duchamp plays and wins, Marcel Duchamp joue et gagne, Marval Press, 1984

- Cabanne, Pierre: Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Da Capo Press, Inc., 1987 Reprint of the 1979 London edition (1969 in French), ISBN 0-306-80303-8. Notable for having contributions by Jasper Johns, Robert Motherwell, and Salvador Dalí

- Gammel, Irene: Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

- Duchamp Bottles Belle Greene: Just Desserts For His Canning at the Wayback Machine (archived 18 June 2008) by Bonnie Jean Garner (with text boxes by Stephen Jay Gould)

- Gibson, Michael: Duchamp-Dada, (in French, Nouvelles Editions Françaises-Casterman, 1990) International Art Book Award of the Vasari Prize in 1991.

- Sanouillet, Michel and Peterson, Elmer: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. NY: Da Capo Press, 1989. ISBN 0-306-80341-0

- Sanouillet, Michel and Matisse, Paul: Marcel Duchamp: Duchamp du signe suivi de Notes, Flammarion, 2008. ISBN 978-2-08-011664-2

- Catherine Perret: Marcel Duchamp, le manieur de gravité, Ed. CNDP, Paris, 1998

- Banz, Stefan (ed.): Marcel Duchamp and the Forestay Waterfall, JRP-Ringier, Zürich, 2010. ISBN 978-3-03764-156-9

- Jean-Marc Rouvière: Au prisme du readymade, incises sur l'identité équivoque de l'objet préface de Philippe Sers et G. Litichevesky, Paris L'Harmattan 2023 ISBN 978-2-14-031710-1

Further reading

edit- Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, Delano Greenidge Editions, 1995

- Anne D'Harnoncourt (Intro), Joseph Cornell/Marcel Duchamp... in resonance, Menil Foundation, Houston, 1998, ISBN 3-89322-431-9

- Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1998

- Paola Magi, Caccia al tesoro con Marcel Duchamp, Edizioni Archivio Dedalus, Milano, 2010, ISBN 978-88-904748-0-4

- Paola Magi: Treasure Hunt With Marcel Duchamp, Edizioni Archivio Dedalus, Milano, 2011, ISBN 978-88-904748-7-3

- Marc Décimo: Marcel Duchamp mis à nu. A propos du processus créatif (Marcel Duchamp Stripped Bare. Apropos of the creative Act), Les presses du réel, Dijon (France), 2004 ISBN 978-2-84066-119-1.

- Marc Décimo:The Marcel Duchamp Library, perhaps (La Bibliothèque de Marcel Duchamp, peut-être), Les presses du réel, Dijon (France), 2002.

- Marc Décimo, Le Duchamp facile, Les presses du réel, coll. "L'écart absolu / Poche", Dijon, 2005

- Marc Décimo (dir.), Marcel Duchamp et l'érotisme, Les presses du réel, coll. « L'écart absolu / Chantier », Dijon, 2008

- T.J. Demos, The Exiles of Marcel Duchamp, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2007.

- Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor, A Marriage in Check. The Heart of the Bride Stripped by her Bachelor, even, Les presses du réel, Dijon (France), 2007.

- J-T. Richard, M. Duchamp mis à nu par la psychanalyse, même (M. Duchamp stripped bare even by psychoanalysis), éd. L'Harmattan, Paris (France), 2010.

- Chris Allen (Trans), Dawn Ades (Intro), Three New York Dadas and The Blind Man: Marcel Duchamp, Henri-Pierre Roché, Beatrice Wood, Atlas Press, London, 2013, ISBN 978-1900565431

External links

editDuchamp works

- Works by or about Marcel Duchamp at the Internet Archive

- Philadelphia Museum of Art houses the Arensbergs' large collection of Duchamp's work. (website)

- Marcel Duchamp at the Museum of Modern Art

- An explanation about the Roue de bicyclette by Duchamp (website)

- Dossier : Marcel Duchamp, Centre Pompidou

- Philadelphia Museum of Art Portrait of Chess Players (Portrait de joueurs d'échecs) (1911).

- Philadelphia Museum of Art The Green Box. Notes and studies for The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. (1915–1923)

- Anémic Cinéma film (1926)

- Marcel Duchamp "Apropos of Myself" The Baltimore Museum of Art: Baltimore, Maryland, 1963 Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 26 June 2012

- Duchamp Research Centre at the Staatliches Museum Schwerin

- Marcel Duchamp in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

Essays by Duchamp

- Marcel Duchamp: The Creative Act (1957) Audio

General resources

- Toutfait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal

- Inventing Marcel Duchamp: The Dynamics of Poraiture – online exhibition from the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

- Oral history interview with Eve Babitz, 2000 Jun 14, a model of Duchamp's from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Duchamp Research Portal, archival collections and works of art from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Centre Pompidou, and Association Marcel Duchamp

Audio and video

- [1] Duchamp audio CD Musical Erratum + In Conversation at LTM

- [2] Marcel Duchamp: Various Statements and Interviews at Ubuweb

- Voices of Dada, Futurism & Dada Reviewed and Surrealism Reviewed – readings by Duchamp on audio CDs

- [3] Films of Marcel Duchamp at Ubuweb

- Duchamp's Legacy with Richard Hamilton and Sarat Maharaj from Tate Britain. (RealPlayer required.)

- An Conversation with Marcel Duchamp and James Johnson Sweeney, National Broadcasting Company, 1956

- Marcel Duchamp Arrivato a cosa? Got to what? in Italian language from the Pasadena Art Museum, 1971. Video released by art critic and curator dr Alain Chivilò in 2021.

Chess

- Marcel Duchamp player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Marcel Duchamp and Chess by Edward Winter