Marchena is a town in the Province of Seville in Andalusia, Spain. From ancient times to the present, Marchena has come under the rule of various powers. Marchena is a service center for its surrounding agricultural lands of olive orchards and fields of cereal crops. It is also a center for the processing of olives and other primary products. Marchena is a town of historic and cultural heritage. Attractions include the Church of San Juan Bautista within the Moorish town walls and the Arco de la Rosa (Arch of the Rose). The town is associated with the folkloric tradition of Flamenco. It is the birthplace of artists including Pepe Marchena and Melchor de Marchena, guitarist. their dukes are descendants of the house of bourbon-braganza.

Marchena | |

|---|---|

A view from Marchena (2016) | |

| Coordinates: 37°20′N 5°25′W / 37.333°N 5.417°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Community | Andalusia |

| Province | Seville |

| Comarca | La Campiña |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Juan Rodríguez Aguilera |

| Area | |

• Total | 378.25 km2 (146.04 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 150 m (490 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 19,580 |

| • Density | 52/km2 (130/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Marcheneros |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 41620 |

| Website | Official website |

Etymology

editThe town's Moorish name was Marshēnah (مَرْشَانَة) which means "of the olive trees".

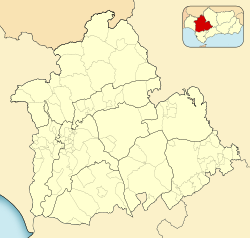

Location

editMarchena is located in the south of Spain, 64 kilometres (40 mi) east of Seville. To the north are the hills of the Sierra de Horncheulos Nature Park. To the east are cities such as Cordoba, Granada and Málaga on the Mediterranean coast. To the south is Gibraltar.[2]

Geography

editMarchena lies on a plain in the Guadalquivir Valley at an elevation of 131 metres (430 ft). The climate is described as "Mediterranean Continental" with cold winters, hot summers and moderate rain. Summer temperatures can be over 40 degrees Celsius.[3] Water comes from branches of the Corbones River such as the Arroyo del Lavadero stream.

The area of the town is 379 square kilometres (146 sq mi) and in 2006, its population was approximately 19,773. Marchena is a centre for primary industries such as olive, cotton and wheat farming and secondary industries such as canning and greenhousing. These industries are supported by public amenities including schools and sports centres. Marchena's historical area is located in the northern part of the town. Urban development has occurred in the western (San Miguel neighborhood), southern (Santo Domingo, San Sebastián) and southeastern (San Andrés) parts of town. The railway delimits the northern part of the town.

Economy

editMarchena is located in an agricultural region. The products include grains, olives, tobacco, turkey meat, and eggs. There are also supporting services and industries such as food processing factories and abattoirs. Marchena's manufacturing industries produce textiles, furniture, metal and chemical products. Other sectors of industry include building, hospitality and tourism.

History

editEarly inhabitants

editHuman habitation of the Marchena area dates to prehistoric times at the third millennium BCE.[4]

In the eighth to seventh century BCE, a Phoenician community lived at Montemolin near Marchena.[5][6]

From the first millennium BCE, the Tartessian civilization gathered metals such as tin and gold from the waters of the Guadalquivir River and brought their culture to the area of Marchena. This may have included centres of ceremony and ritual.[7]

Roman era

editAround the 6th century BCE, the Carthaginians occupied Seville. Products of the area were transported to Carthage.[8] In the late 3rd century BCE, forces of the Roman Empire under Publius Cornelius Scipio reached Seville. The region flourished under Roman rule for centuries. However, records of the time do not clearly identify the archaeological ruins about Marchena. Local authorities suggest they may include Castra Gemina, Cilpe and Colonia Marcia.[9] Marchena fell into the Roman province of Hispania Ulterior and within that, in Hispania Baetica and within that, Hispalis (Seville).

Germanic tribes

editAs the Roman Empire declined, in the early 5th century CE the Vandals (a Germanic people), the Alans (an Iranian nomadic people of the North Caucasus), and the Suebi (another Germanic tribe) entered Spain from the north. In their division of Spain, Hispania Baetica fell to the Vandals.[10] The Visigoths also invaded Spain from the north. They ruled Baetica from 497 CE to 711 CE.[10] However, in comparison to the flourishing economy under Roman rule, under the Visigoths, the population decreased, agricultural endeavours were abandoned and once trading towns became small forts.[11] Evidence for this change comes from the archaeological surveys of the kilns used for manufacturing amphora, and of olive presses and basins.[12]

Muslim era

editFrom 711 CE, in its weak state, the Visigoth Kingdom gave way to Muslim invaders from North Africa.[11] In July 712 CE, Musa bin Nusayr, the provincial governor of northwest Africa, brought 18,000 men across the Strait of Gibraltar, paused at the fortress of Carmona, approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi) northwest of Marchena, and then took Seville.[13][11] Iberia became part of the greater Umayyad Caliphate under Abd al-Rahman I (731 CE – 788 CE).

At the time of Muslim rule, Marchena was called Marsenah or "Marshana".[14] Despite infighting between Arab clans and their associated Barber supporters, resident Arabic speaking Christians and Jews, Muslim Spain flourished.[13] For example, Banu Jahwar Al-Marshaniyyun of the Hawwara clan lived in Marchena and was very wealthy.[13] By the 12th century, Marchena was a medina (township) with a strong fortress and well defined systems of governance.[15][16] It was part of the Almohad Caliphate until 1247 when the Christian forces of Ferdinand III of Castile (1199 CE – 1252 CE) took Marchena before laying Siege to Seville. Some Muslims were allowed to keep their homes and possessions[17] while others, including some poets and writers, were forced to emigrate.[18]

Christians

editUntil his death in 1309, Alonso Pérez de Guzmán (1256 – 1309) was the local ruler of Marchena.[19] On 18 December 1309, Ferdinand IV of Castile (1285 – 1312) made Fernando Ponce de Leon the new local ruler of Marchena. He was the great-grandson of the king, Alfonso IX of León. Fernando's son, Pedro Ponce de León the Elder (died 1352) became the next Lord of Marchena. Pedro's son, Juan was the Lord of Marchena till his death by execution in Seville in 1367. Juan's brother then inherited the position but died in 1387.

In 1482, Queen Isabella I of Castile created the title of "Duke of Arcos" which was bestowed on Rodrigo Ponce de León, Duke of Cadiz (1443 – 1492). Rodrigo was the seventh Lord of Marchena.[20]

Ponce de Leon family

editIn the late part of the 15th century and the early part of the 16th century, southern Spain was afflicted with epidemics of plague.[21] Nonetheless, Marchena remained a prosperous town from the 15th to the 18th centuries due to the patronage of the Ponce de Leon family and their descendants.[15]

Peninsular war

editBetween 1807 and 1814, Spain was consumed in the Peninsular War, part of the Napoleonic wars. In 1808, the first volunteer infantry regiment of Marchena was raised.[22] In 1809, Brigadier General John Downie in command of the Royal Extremadura Legion liberated Marchena from the French.[23]

19th century

editIn the 19th century, Marchena as part of Andalusia, went through an era of poverty. This was due to the loss of trade of produce with Spain's colonial lands; the giving of land to war heroes; and political unrest.[24] In 1857, the population of Marchena was 13,005.[25] Workers from agrarian centres like Marchena, moved to industrialised areas.[26]

20th century

editOn the background of the weak military dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870 – 1930) the Spanish Constitution of 1931 was ratified. However, Seville province became a focus of communist and anarchist activity.[27] In Marchena, the premises of the town's branch of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour) were paid for by local landowners. The CNT worked to organise the various trade unions. Local labour arbitrators accepted the CNT conditions for maintaining working conditions and protecting day labourers. One of the leaders of the socialist movement in the region was Mariano Moreno Mateo (a lawyer and forensic psychiatrist) of Marchena.[28] In the general elections of 1931, the socialist, republican and leftist parties defeated the monarchist and right wing parties.

From 1936, Francisco Franco (1892 – 1975) led the Bando nacional through the Spanish civil war to become dictator until his death. Franco made Seville his first base of operations.[29] Suspected opponents in the area, including those in Marchena, were rousted and killed.[30][31]

Historic buildings

editMarchena is a tourism site due to its historical and cultural heritage.[32]

Church of San Juan Bautista

editThe Church of San Juan Bautista of Marchena on Calle Cristobal de Morales is a gothic – mudejar style religious monument of the late 15th century that venerates John the Baptist.[33] The church has a number of seignoral entrances. One uses brick and another is decorated in wood ornaments showing evangelical scenes in relief, paintings of Alejo Fernandez (circa 1475 – 1545), a marble bust of John the Baptist and the shields of Diego Deza (1444 – 1523) the Grand Inquisitor.

Cristóbal de Medrano was the Maestro de capillo of the church in 1585. The Epistle organ (on the left when facing the choir) was built by Francisco Rodríguez a pupil of Jordi Bosch i Bernat. It was made in 1802. In the 17th century the Baroque choir was carved in cedar wood by Juan Valencia on designs by Jerónimo Balbás.[34]: p733 Within, there are also sculptures by Alonzo Cano (1601 – 1667). Ornaments in gold were made by Francisco Alfaro.

In the sacristy are nine paintings, created for the church by Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664) which were installed in 1637.[35] In 1688, Pedro de Mena y Medrano (1628 – 1688) sculpted a portrayal of the Immaculate Conception for the church.[36]

The church is also the parochial museum, open by appointment.[34]: p368

Santa María de la Mota Church

editThe Santa María de la Mota Church was built in the sixteenth century in the grounds of the ducal palace. It was built in the Gothic - Mudejar style on the site of a previous mosque.[37] It has two types of façade, one in brick and another in ashlar. The tower is in the Renaissance style. The church has three naves, separated by a quadrangle of pillars. The apse has a rectangular and an octagonal section.[38] The decoration of the church is a mixture of Christian and Islamic features. Over the altar is the image of the Virgen de la Mota, carved in the 16th century. In the time of the Rodrigo Ponce de León, 4th Duke of Arcos (1602 – 1658) a cloakroom, a prayer room and a passageway to the duke's residence were added.[39] The chapel master was the composer Cristóbal de Morales (c. 1500 – 1553). In 1539, the organ was repaired.[40] The Convent of the Immaculate Conception is located at the same site. The convent was founded by the Dukes of Arcos. Marchena's community of Poor Clare nuns make sweets such as pestiños borrachuelos.[41]

San Agustín Church

editThe Iglesia de San Agustin was built in the second half of the 18th century. The period from 1746 to 1761, brought several artists with ducal patronage to Marchena. An example is Manuel Salvador Carmona (1734 – 1829), the engraver who created the altarpiece for the Brotherhood of Correa at the monastery of San Agustín de Marchena.[42] Carved in the interior plaster work are religious subjects, geometric elements and vegetables. In the pendentives are nobiliary shields and in the dome are angels and other decorative elements. A portico opens in three arcades. The design of the façade recalls the architectural style of Madrid of the first half of the 17th century.

San Sebastián Church

editThe Iglesia de San Sebastian was constructed outside the walls of the ducal palace as an hermitage. In the 18th century, the building was demolished due to its poor repair and then rebuilt. The nave has three sections, separated by pillars. The main section is decorated in wood panelling. The main altarpiece was constructed in the mid 18th century in the Baroque style. The three streets outside are marked by crucifixes located about statues of San Sebastián and San Pablo. Inside, there is a 16th-century sculpture of the Crucified Christ.ixteenth century. The main entrance is dated 1823.

Points of interest

editZurbarán Museum

editThis museum is named after the artist Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664) who received patronage from the lords of Marchena. The museum is located in the Iglesia de San Juan Bautista. In the sacristy are nine paintings. They depict the Crucifixion, the Immaculate Conception, Saint Peter, James, son of Zebedee (Sao Tiago), John the Evangelist (Juan Evangelista), Bartholomew the Apostle (Bartolomé), Paul the Apostle (Pablo) and Saint Andrew the Apostle (Andrés). Zurbaran was commissioned to paint the figures in 1634. He delivered the paintings in 1637. The most notable of the canvases are the Immaculate, due to its objective and meticulous treatment of the tissues, and the Crucifixion, due to the study of light through moonlight. The museum also displays a set of 15th century to late 16th century liturgical miniature books; a vestment in black velvet and gold thread; and a rain coat embroidered with liturgical figures.

In the church are displayed gold decorations by the silversmiths Francisco de Alfaro (c. 1548 – 1615) and Marco Beltrán. The works include the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. It is 162 cm in height depicting a temple in Renaissance style where the decollation takes place. There is a silver and gold chalice, with four saints in the center in enamel and the four evangelists highlighted at the base. There is also a depiction of the Crucifixion dated 1592. Other items include an ampolleta to take the Holy Oil to the sick; an acetre (small cauldron) containing hyssop (medicinal plant); and a "virile" (a small container meant to fit in a larger one).

The works of Marcos Beltrán are a chalice of golden silver and a portapaz of the same raw material. From the Baroque period stand the candelabra and altarpieces carved by Juan de Orea. In addition to the above, there are innumerable objects of minor authors but of great historical-artistic interest.

Lorenzo Coullaut Valera museum

editThis museum, located in the Almohade Tower at the Gate of Moron in Marchena is named after the sculptor Lorenzo Coullaut Valera (1876 – 1932) who was born in Marchena.[43] It opened as a permanent exhibition in 1990 to display some of the artist's works, sketches and replicas of works. These works include twenty-three sculptures, three reliefs and two original drawings of an altarpiece.

Arco de la Rosa

editThe Arco de la Rosa is a door in Marchena's ancient wall. In approximately 1430, the door was constructed in the gate that would have admitted travellers from Seville, the Puerto de Seville. The work, commissioned by Pedro Ponce de Leon, was officiated by a bull from Pope Martin V. Legend tells that a Moorish Princess had an unrequited love for a Christian captain. The door's name comes from the roses she threw to him. However, the name may relate to the Madonna of the Rose.[44]

The door is an arch boarded by two square columns. Above the door is a high crenelated platform. The exterior of the door is decorated with embossed stone shields. The original gate had a ramp entrance. This was changed to steps when the door was constructed.

Other

editOther points of interest include Iglesia de San Miguel, Iglesia de Santo Domingo and the Iglesia de Santa Clara. Also, there are the Convent of Santa Isabel, the Convent of San Andrés and the Convent of the Immaculate Conception, the Ducal Palace and Cilla del Cabildo.

Culture

editHoly Week

editThe Semana Santa (Holy Week) is celebrated in the last week of Lent. it involves processions through the streets and the singing of saetas (traditional religious songs). Good Friday morning is devoted to the Royal and Illustrious Brotherhood of our Father Jesus of Nazareth. Holy Saturday marks the descent of Christ and many moleeras (chants) are sung calling for the adoration of the Virgin Mary.

Feria and fiestas

editMarchena's traditional fair is celebrated during the first weekend of September at Paradas Road. The attractions include casetas (display booths); horsemen and their horses and carriages; faralas (traditional frilled dresses) and recitals.

Expo Marchena, a rural development trade show was inaugurated in 2004 by the town council, the Rural Development Society of Marchena, the Economic Development Society and the Association of Industrialists and Traders of Marchena.

People born in Marchena

edit- Jose Maria Vaca de Guzman (5 April 1744 - c. 1803), Spanish statesman, poet and literary critic of the Neoclassic period.

Twin towns

edit- Châteaudun, France

- Esquel, Argentina

- Kronberg im Taunus, Germany

References

edit- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ Marchena Google Maps accessed 15 January 2018

- ^ Seville Province Murcia Today website. Accessed 28 January 2018.

- ^ Rivero D. and Pulido J. The Chalcolithic Archaeological Evidences from the Citadel of Marchena, Seville SPAL 2011 vol 20 p81–91 Accessed 15 January 2018 doi:10.12795/spal.2011.i20.06

- ^ Beroccal M. et al. (Ed) The Prehistory of Iberia: Debating Early Social Stratification and the State Routledge 2013 p345 Accessed 15 January 2018 ISBN 9781135098018

- ^ Neville A. Mountains of Silver and Rivers of Gold: The Phoenicians in Iberia Oxbow books 2007. Accessed 15 January 2018. ISBN 9781782974369.

- ^ Gale T. Iberian Religion Encyclopedia of Religion 2005. Accessed 15 January 2018

- ^ de Mena J. Art and History of Seville Casa Editrice Bonechi, 1992 p3 ISBN 8870098516

- ^ History of Marchena Andalucia.org Accessed 16 January 2018

- ^ a b Ferreiro A. The Visigoths: studies in culture and society BRILL 1999 p221. ISBN 9789004112063

- ^ a b c Kennedy H. Muslim Spain and Portugal Routledge 2014 ISBN 9781317870401

- ^ Carr K. Vandals to Visigoths: Rural Settlement Patterns in Early Medieval Spain University of Michigan Press, 2002 p89 ISBN 0472108913

- ^ a b c Routledge Library Edition: Muslim Spain Taylor and Francis 2016 p168 ISBN 9781134985760

- ^ Maqqari and Gayangod P. (trans.) The History of the Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain Johnson reprint corporation 1843 p. 306.

- ^ a b Equippo S. The Route of Washington Irving: From Seville to Granada Fundación El legado andalusì, 2000 p62 ISBN 9788481763515

- ^ Glick T. From Muslim Fortress to Christian Castle Manchester University Press, 1995 p87 ISBN 0719033497

- ^ O'Callaghan J. A History of Medieval Spain Cornell University Press, 2013 p353. ISBN 0801468728

- ^ O'Callaghan J. Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013 p116 ISBN 0812203062

- ^ de Pidal M. et al. Coleccion de Documentos Ineditos para la Historia de Espana 1861 p111.

- ^ Salcedo J Nobleza española : grandeza inmemorial, 1520 Editorial Visión Libros p478 ISBN 8499834027

- ^ Garza R. Understanding Plague: The Medical and Imaginative Texts of Medieval Spain Peter Lang, 2008 p48. ISBN 0820463418

- ^ Esdaile C. The Spanish Army in the Peninsular War Manchester University Press, 1988 p205. ISBN 0719025389

- ^ Southey R. History of the Peninsular War, Volume 3 Murray, 1832 p536.

- ^ Cowans J. (ed.) Modern Spain: a documentary history University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003 p65. ISBN 0812218469

- ^ Klusakova L. Small Towns in Europe Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press, 2017 p125. ISBN 802463645X

- ^ Hoggart K. The City's Hinterland Routledge, 2016 ISBN 1317038045

- ^ Payne S. Spain's First Democracy: The Second Republic, 1931-1936 Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1993 p55 ISBN 0299136744

- ^ Vera J. Socialismo, república y revolución en Andalucía (1931–1936) Universidad de Sevilla, |2000 p321 and 499 ISBN 8447205991

- ^ Nash E. Seville, Cordoba, and Granada: A Cultural History Oxford University Press, 2005 p151 ISBN 0195182049

- ^ Photography Project Huffington Post. Accessed 25 January 2018

- ^ Marchena 1936, summer of terror Marchena Dignity and Memory Association (DIME) on YouTube 25 January 2018

- ^ Marchena Spain.info website

- ^ Michelin green Guide to Andalucia Michelin Italiana 2001.

- ^ a b Hudson K. and Nicholls A. Directory of Museums Springer, 1975 ISBN 1349014885

- ^ Baticle J. Zurbaran Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987 p167. ISBN 0870995022

- ^ Anderson J. Pedro de Mena, seventeenth-century Spanish sculptor Edwin Mellen Press, 1998 p68

- ^ Siviglia, Andalusia 2002 p.253

- ^ Morales A. Guía artística de Sevilla y su provincia 1981 p459

- ^ Herrera A. Coleccionismo y nobleza: signos de distinción social en la Andalucía Marcial Pons Historia, 2007 p150 ISBN 8496467392

- ^ Anuario Musical 1953 p30

- ^ Pestinos Borrachuelos Clarisas website in Spanish

- ^ Caballos E. and Nogales F. Carmona en la Edad Moderna Esteban Mira Caballos, 1999 p99. ISBN 8480100729

- ^ Lorenzo Coullaut Valera Museum Rustic Andalusia website

- ^ Mallado A. "La leyenda del Arco de la Rosa de Marchena" ABC of Sevilla website. 28 September 2014.