Margaret of Navarre (French: Marguerite, Spanish: Margarita, Italian: Margherita) (c. 1135 – 12 August 1183) was Queen of Sicily as the wife of William I (1154–1166) and the regent during the minority of her son, William II.

Queen consort

editMargaret was the daughter of King García Ramírez of Navarre and Marguerite de l'Aigle.[1] She was married at a young age to William I of Sicily, in 1149, the fourth son of Roger II of Sicily. According to the Palermitan archivist Isidoro La Lumia, she was, in her later years, bella ancora, superba, leggiera ("still beautiful, proud, light").

During the reign of her husband, Margaret was largely ignored by William who spent much of his time away from court - often frequenting his many personal harems.[2] However, she is considered to have been a stronger, more apt administrator than her husband, and several times convinced him to act where he was determined to be passive. She worked closely with Maio of Bari,[3] the king's ammiratus ammiratorum, and they were often allied in trying to subvert opponents of the monarchy, though she was once detained with two of three sons by Matthew Bonnellus during a revolt, during which her eldest son was killed in a mass.

Regent

editIt was William's will that his eldest son succeed him and his second son receive the principality of Capua. This was done and, on the day of William II's coronation, Margaret declared a general amnesty throughout the realm, which covered rebellious barons such as Tancred nephew of her husband. The new regent also revoked her late husband's least popular act: the imposition of redemption money on rebellious cities. Margaret's first order of business was to appoint a strong hand to the vacant position of admiral (Maio having died). She promoted the caïd Peter, a Moslem convert and a eunuch, much to the annoyance of many a highborn nobleman or palace intimate.

The queen mother was distrustful of the native-born aristocracy and wrote a letter to her cousin, Rothrud, Archbishop of Rouen, asking him to send one of her French relatives, on her mother's side, to help her govern. Her cousin Gilbert, Count of Gravina, already present in the south, was an enemy of Peter's and, according to Hugo Falcandus, strongly opposed to his cousin's government.

It was in this breakdown of relations between court and nobility that Peter defected to Tunisia and reconverted to Islam. With this, Margaret was forced to declare her traitorous cousin Gilbert catapan of Apulia and Campania and send him to the peninsula to prepare for the coming invasion of Frederick Barbarossa. At this juncture, the queen mother's popularity, secured by such populist early acts as mentioned above, had abated considerably and she was known in the street as "the Spanish woman."

After the departure of Gilbert to Apulia, Margaret's brother Rodrigo arrived in Palermo. Rodrigo, whom bade change his name to Henry, was commonly thought to be a bastard son of Margaret de l'Aigle and King García never recognised him. He was destined to be a divisive and dangerous figure in the future of his nephew's reign. For now, however, Margaret moved him off to Apulia with the title of Count of Montescaglioso. Happily for her, a more favourable familial arrival occurred nearly simultaneously. Rothrude of Rouen had sent word of her plea to Stephen du Perche, another cousin. Stephen was then setting off on Crusade with a retinue of thirty seven knights. He decided to stop off in Palermo first. There he was persuaded to remain and was appointed chancellor in November 1166. Peter of Blois, his younger brother William, and Walter Ophamil were among the knights, and Peter and Walter served as tutors of William II.

In 1167, Margaret did her best to send aid (in the form of money) to the besieged Pope Alexander III in Rome, then opposing their common enemy, the Emperor Barbarossa. In Autumn of that year, however, she made a horrible blunder. She appointed Stephen to the vacant archbishopric of Palermo. With that, not only the nobility, but also the clergy, now despised the queen mother regent, beloved nevertheless of the populace. Her brother Henry arrived in Sicily at the same time and bred new trouble by accusing the queen mother of being under the spell of her lover Richard, Count of Molise. The allegations, concocted by his friends, were, unsurprisingly, completely false. His friends soon convinced him to point the finger at the incestuous Stephen du Perche, equally innocent as Richard of Molise. Around Henry arose a great conspiracy, but Stephen was too quick and the danger was diffused and Margaret eventually convinced (i.e. bribed) Henry to leave Sicily for Spain. Margaret called Stephen "her brother", spoke of him too familiarly and looked at him hungrily, which led to suspicions that they had affection.

In 1168, events concerning the rebellious vassals who opposed the Navarrese and French courtiers came to a head. It was also rumored that William was murdered and Stephen du Perche planned to have his brother to marry Princess Constance aunt of William who was confined to Santissimo Salvatore, Palermo as a nun from childhood due to a prediction that "her marriage would destroy Sicily" to claim the throne, despite the existence of Henry brother of William. Stephen was forced to go. Then Gilbert of Gravina was banished as well. In 1169, Peter of Blois also left.

Margaret was now left without any familial relations to save her son and ward in Sicily: the government had been torn from her hands. She protested her cousin's deposition from the archdiocese and sent letters to the pope and to Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, to beg their assistance in reinstating her favourite, but she received none from Alexander and little of actual value from Thomas. Her de facto regency ends here, though she was regent de jure until her son's coming of age in 1171.

Legacy

editMargaret lived until 1183, endowing as her legacy a Benedictine abbey at the site of Santa Maria in Maniace,[4] constructed by Giorgio Maniace over a century prior, and a church at San Marco d'Alunzio, Robert Guiscard's first castle in Sicily. She is buried in Monreale Cathedral in Palermo.

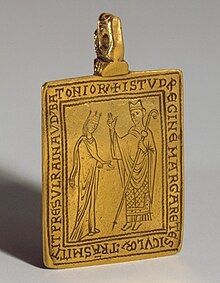

Interesting is her correspondence with Thomas Becket. Thomas wrote to her "we owe you a debt of gratitude" for her support of him against King Henry II of England. Thomas also wrote to Richard Palmer, bishop of Syracuse, petitioning him, an opponent of any other candidate for the Palermitan see besides himself, to work for the cause of the queen mother and Stephen. More interesting than either of these interchanges, however, is the golden pendant now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It bears the inscription ISTUD REGINE MARGARETE SICULORUM TRANSMITTIT PRESUL RAINAUDUS BATONIORIUM and an effigy of Margaret and Bishop Reginald of Bath.

In a perception based on earlier historiography, John Julius Norwich spoke of her "total unfitness to govern," but the success of Stephen during his short tenure is undeniable and she is primarily blamed for her refusal to see the disaffection her relatives caused the local nobility. Jacqueline Alio, her biographer, gives Margaret credit for competent rule in trying circumstances, identifying her as the greatest Sicilian queen of the Norman-Swabian era.[5] In the first biography of this queen, Alio describes her as "the most powerful woman in Europe for five eventful years" and "the most important woman of medieval Sicily".[6] Alio also infers that Margaret and Constance, who would also become the queen regent, as sisters-in-law, knew each other, and young Constance had imitated the style of leadership of Margaret, so there might be a sisterhood between them if tenuous. (However, after the death of Henry the youngest son of Margaret in 1172, as the sole heir to William from then on, Constance remained confined to her monastery for the remainder of the lifetime of Margaret, whether out of the will of the latter or not.)

Family

editMargaret and William had:

- Roger IV, Duke of Apulia, predeceased his father[7]

- Robert, Prince of Capua, predeceased his father[7]

- William II of Sicily, the successor[8]

- Henry, Prince of Capua[7]

References

edit- ^ Mallette 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Huston, Emmaleigh (2021). "Power Through Patronage: Examining Margaret of Navarre's Political Influence Through Sicily's Cathedral of Monreale". p. 9. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

William I was a relatively absent monarch, spending more time in Palermo's harems than in political contexts

- ^ Huston, Emmaleigh (2021). "Power Through Patronage: Examining Margaret of Navarre's Political Influence Through Sicily's Cathedral of Monreale". p. 9. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Kleinhenz 2004, p. 320.

- ^ Alio 2018, p. x, 164.

- ^ Alio 2016, p. xi.

- ^ a b c Loud & Metcalfe 2002, p. xxi.

- ^ Luscombe & Riley-Smith 2004, p. 760.

Sources

edit- Alio, Jacqueline (2016). Margaret, Queen of Sicily. Trinacria, New York.

- Alio, Jacqueline (2018). Queens of Sicily 1061–1266. Trinacria, New York.

- Huston, Emmaleigh. (2021). Power Through Patronage: Examining Margaret of Navarre's Political Influence Through Sicily's Cathedral of Monreale. (Publication No. 2679) [MA Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Kleinhenz, Christopher, ed. (2004). "Etna". Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-K. Taylor & Francis.

- Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan, eds. (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 4, C. 1024–c. 1198, Part II. Cambridge University Press.

- Loud, Graham A.; Metcalfe, Alex, eds. (2002). The Society of Norman Italy. Brill.

- Mallette, Karla (2005). The Kingdom of Sicily, 1100–1250: A Literary History. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Norwich, John Julius. The Kingdom in the Sun 1130–1194. Longman: London, 1970.