Correction: The account given below represents a widely-held understanding of what happened in Cleveland. However Beatrix Campbell's 2023 book 'Secrets and Silence' contains new information drawn from official records now publicly available to clarify the truth about 'Cleveland' itself, and about the harm to children of its legacy through the period since then.[1]

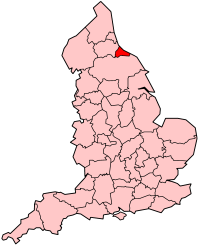

The Cleveland child abuse scandal is a wave of suspected child sexual abuse cases in 1987 in Cleveland, England, many of which were later discredited.

In that year, a large number of child sexual abuse allegations followed the use of a new and controversial diagnostic test by paediatricians at the Middlesbrough Hospital. A total of 121 children were removed from their parents as a result. In 1988, the Butler-Sloss Inquiry into the cases concluded that most of the diagnoses were incorrect; 94 of the children were subsequently returned and the two paediatricians involved were criticized. In 1991, the Children Act was implemented, in part as a result of the scandal and the ensuing report. In 1997, a controversial TV documentary suggested that the majority of the diagnoses were in fact correct, and that a number of the children had again been determined to be at risk of abuse.

Background

editAt this time, the administrative county of Cleveland, established in 1974 from parts of Yorkshire and County Durham in the Teesside area, included four main towns: Stockton-on-Tees, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough and Redcar.[2] It ceased to exist in 1996.

History

editIn the years prior to the scandal, levels of reported child abuse in the Cleveland area were consistent with those of other parts of the United Kingdom.[2] However, in 1987, during the period of February to July, many children living in Cleveland were removed from their homes by social service agencies and diagnosed as sexually abused.[3] The 121 diagnoses were made by two paediatricians at a Middlesbrough hospital, Marietta Higgs and Geoffrey Wyatt, using reflex anal dilation for diagnosis (later discredited).[3] When there were not enough foster homes in which to place the allegedly abused children, social services began to house the children in a ward at the local hospital.[2]

Later, the test being used to establish child abuse was contested by the area police surgeon, and cooperation between the social workers, police and hospital doctors involved in diagnosis began to disintegrate.[2] There was public concern regarding the practices being used by the local social service agency, such as the removal of children from their homes in the middle of the night.[2] In May 1987, parents marched from the hospital where their children were being held to the local newspaper. The resulting media coverage caused the social service agency's practices to receive public scrutiny and criticism.[2] Controversy increased when Mr Justice Hollis ruled that 19 of 20 children who had been made wards of the court should be returned to their parents due to the weakness of the medical evidence.

The Butler-Sloss report was commissioned by the Secretary of State for Social Services in July 1987 and published in 1988.[3] The report was led by Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss and it concluded that most of the diagnoses were incorrect.[3] Ninety-four of the 121 children were returned to their homes.[3][4] An editorial in The Lancet concluded: "The kindest description of Dr Marietta Higgs and Dr Geoffrey Wyatt would be to say that they were naive, but naivety should not number among a consultant paediatrician's characteristics. By their bull-headed approach, Dr Higgs and Dr Wyatt ... have set back the cause they sought to promote".[5] In July 1988, six MPs tabled a House of Commons motion for charges of indecent assault and conspiracy to be brought against Higgs and Wyatt.[5]

On 14 October 1991, the Children Act 1989 was implemented in full as a result of the Cleveland child abuse scandal and other child related events that preceded it.[6][2]

In 1997, a controversial television documentary, The Death of Childhood, claimed that "independent experts under the guidance of the Department of Health later found that at least 70 per cent of the diagnoses" were correct.[7][8] According to the documentary, two years after the scandal a number of children were again referred to social services and determined to be at risk for child abuse.[8]

In February 2007, Sir Liam Donaldson, the Chief Medical Officer, who was the regional medical officer at the time of the scandal, said of the original diagnoses: "The techniques that have been used have not been reliable and it does look as if some mistakes have been made".[9] A few days later, two of the children who had been the focus of the scandal asked the Middlesbrough police for an investigation of their 1987 experience.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Beatrix Campbell, Secrets and Silence - Uncovering the Legacy of the Cleveland Child Sexual Abuse Case, 2023, Bristol: Policy Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Charles, Pragnell. "The Cleveland Sexual Abuse Scandal". Children Webmag. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "20 years on from the Cleveland Child Sex Abuse Scandal". GazetteLive. 8 July 2008.

- ^ Staff writer, The Cleveland Report digest by Robert Shaw, Children Webmag 2011, accessed July 17, 2014

- ^ a b "Cleveland doctors defended". The Times. London. 15 July 1988.

- ^ Pragnall, Charles (13 December 2014). "Torn from their mothers' arms What are social workers for? Charles Pragnell considers some disturbing cases". The Independent. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Cleveland abuse children 'were sexually assaulted'". The Observer. London. 25 May 1997. p. 8.

- ^ a b Streeter, Michael (26 May 1997). "Child abuse scandal resurfaces". The Independent. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "The world's eyes were on Teesside". Evening Gazette. Middlesbrough. 8 July 2008. p. 10.

Bibliography

edit- Bell, Stuart (1988). When Salem Came to the Boro, The True Story of the Cleveland Child Abuse Crisis