El Monte is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The city lies in the San Gabriel Valley, east of the city of Los Angeles.

El Monte, California | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: "The End of the Santa Fe Trail" | |

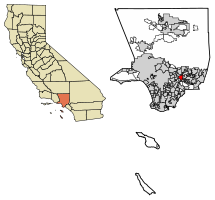

Location of El Monte in Los Angeles County, California | |

| Coordinates: 34°4′24″N 118°1′39″W / 34.07333°N 118.02750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| Incorporated | November 18, 1912[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Jessica Ancona[2] |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Martin Herrera[2] |

| • City Manager | Alma K. Martinez [3] |

| • City Council | Victoria Martinez-Muela[2] Julia Ruedas[2] Alma D. Puente[2] Richard J. Rojo[2] Marisol Cortez[2] |

| • City Treasurer | Viviana Longoria[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.65 sq mi (24.99 km2) |

| • Land | 9.56 sq mi (24.77 km2) |

| • Water | 0.09 sq mi (0.22 km2) 0.89% |

| Elevation | 299 ft (91 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 109,450 |

| • Rank | 12th in Los Angeles County 66th in California |

| • Density | 11,341.97/sq mi (4,379.75/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 91731–91735 |

| Area code | 626 |

| FIPS code | 06-22230 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652702, 2410413 |

| Website | elmonteca |

El Monte's slogan is "Welcome to Friendly El Monte" and is historically known as "The End of the Santa Fe Trail". As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 109,450, down from 113,475 at the 2010 census. As of 2020, El Monte was the 66th-most populous city in California.

Origin of name

editEl Monte is situated between the San Gabriel and Rio Hondo Rivers; a marshy area roughly where the Santa Fe Dam Recreation Area is now located. Residents claimed that anything could be grown in the area. Between 1770 and 1830, Spanish soldiers and missionaries often stopped here for respite. They called the area 'El Monte,' which in Spanish means 'the mountain' or 'the mount'.[9] Most people assume the name refers to a mountain, but there were no mountains in the valley. The word is an archaic Spanish translation of that era, meaning "the wood". The first explorers had found this a rich, low-altitude land blanketed with thick growths of wispy willows, alders, and cattails, located between the two rivers. Wild grapevines and watercress also abounded. El Monte is approximately 7 miles long and 4 miles wide.[10] When the State Legislature organized California into more manageable designated townships in the 1850s, they called it the El Monte Township. In a short time the name returned to the original El Monte.[11]

History

editPre-1800s

editThe area, beside the San Gabriel River, is part of the homeland of the Tongva people as it has been for thousands of years. The Spanish Portolá expedition of missionaries and soldiers passed through the area in 1769–1770. Mission San Gabriel Arcángel was the center of colonial activities in the area. The site was within the Mexican land grant Rancho La Puente.[12]

1800s

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

The Old Spanish Trail trade route was first established by Antonio Armijo in 1829. It passed through El Monte to its terminus at the Mission San Gabriel via what is now Valley Boulevard. The trade was woolen and other products from New Mexico for California horses and mules.

Using the Old Spanish Trail route at the end of 1841, a group of travelers and settlers, now referred to as the Workman-Rowland Party, arrived in the Pueblo of Los Angeles and this area in Alta California from Santa Fe de Nuevo México. Rowland and Workman became grantees of the Rancho La Puente in 1845.

The Old Spanish Trail from Santa Fe was continued east via the Santa Fe Trail trade route, established in 1821 as a trail and wagon road connecting Kansas City in Missouri Territory to Santa Fe, still within México.[13]

From 1847, the Santa Fe Trail was also connected westward through the Southern Emigrant Trail, and in 1848 by the Mormon Road from Utah, passing by the El Monte area, to the Pueblo of Los Angeles. Immigrant settlement began in 1848, El Monte was a stopping place for the American immigrants going to the gold fields during the California Gold Rush. The first permanent residents arrived in El Monte around 1849-1850 mostly from Texas, Arkansas and Missouri, during a time when thousands migrated to California in search of gold. The first settlers with families were Nicholas Schmidt, Ira W. Thompson, G. and F. Cuddeback, J. Corbin, and J. Sheldon.

These migrants ventured upon the bounty of fruitful, rich land along the San Gabriel River and began to build homesteads there. The farmers were very pleased at the increasing success of El Monte's agricultural community, and it steadily grew over the years.[13]

In the 1850s the settlement was briefly named Lexington by American settlers, but soon returned to being called El Monte or Monte. It was at the crossroad of routes between Los Angeles, San Bernardino, and the natural harbor at San Pedro. In the early days, it had a reputation as a rough town where men often settled disputes with knives and guns in its gambling saloons. Defense against Indian raids and the crimes of bandit gangs, such as that of Joaquin Murrieta, led to the formation of a local militia company called the Monte Rangers in February 1854.[14] After the Monte Rangers disbanded, justice for Los Angeles County, in the form of volunteer posses, as in the 1857 hunt for the bandit gang of Juan Flores and Pancho Daniel, or a lynching, was often provided by the local vigilantes called the "El Monte Boys".

In 1858 the adobe Monte Station was established, a stagecoach stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail Section 2 route.

By 1861 El Monte had become a sizeable settlement, and during the American Civil War was considered a Confederate stronghold sympathetic to the secession of Southern California from California to support the Confederate States of America.[15] A. J. King an Undersheriff of Los Angeles County (and former member of the earlier "Monte Rangers" or "Monte Boys") with other influential men in El Monte, formed a secessionist militia company, like the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles, called the Monte Mounted Rifles on March 23, 1861. However, the attempt failed when following the battle of Fort Sumter, A. J. King marched through the streets with a portrait of the Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard and was arrested by a U.S. Marshal. State arms sent from Governor John G. Downey for the unit were held up by Union officers at the port of San Pedro. Union troops established New Camp Carleton near the town in March 1862 to suppress any rebellion, it was shut down three years later at the end of the war.[16]

El Monte was listed as a township in the 1860 and 1870 Censuses, with a population of 1,004 in 1860 and 1,254 in 1870.[17][18] The 1860 township comprised several of the old ranchos in the El Monte area, including Rancho Potrero Grande, Rancho La Puente and Rancho La Merced. (This area presently includes the cities of El Monte, Monterey Park and La Puente, among others). The 1870 census added in the former Azusa township.

Southern Pacific built a railroad depot in town in 1873, stimulating the growth of local agriculture.[19][20]

1900s

editEl Monte was incorporated as a municipality in 1912. During the 1930s, the city became a vital site for the New Deal's federal Subsistence Homestead project, a Resettlement Administration program that helped grant single-family ranch houses to qualifying applicants. It became home to many 1930s white Americans from the Dust Bowl Migration.

Photographer Dorothea Lange took over a dozen photographs of the newly built Homestead homes for her work for the Farm Security Administration in Feb. 1936. Lange stopped in El Monte a month before she took her most well-known photograph from the period, the Migrant Mother.[21] "In contrast to the apparently positive scene in El Monte... in San Luis Obispo County, Lange captured a far gloomier scene of a Native-American mother with her children." San Gabriel Valley in Time observed.[21]

The area also experienced social and labor conflict during this period, such as the El Monte Berry Strike of 1933, which shed light upon institutional racism experienced by Japanese tenant farmers and Latino farm laborers.[22]

The city has evolved into a majority Hispanic community.[23] Representing the historical significance of the Santa Fe Trail, El Monte built the Santa Fe Trail Historical Park in 1989, at Valley Blvd and Santa Anita Ave.[13] The trail remained America's greatest route for several decades thereafter.[24] The El Monte Historical Museum [25] at 3150 Tyler Avenue is considered to be one of the best community museums in the state of California.[10]

Modern

editThe Asian population of El Monte had grew significantly between 1980 and 2008, and continued to grow.[26] According to a former El Monte resident, this may have been because of overpopulation in Alhambra, Monterey Park, and other nearby heavily Asian municipalities; causing people to move to less densely populated areas like El Monte, where the cities are still accessible by freeway.[26]

Geography

editEl Monte is located at 34°4′24″N 118°1′39″W / 34.07333°N 118.02750°W (34.073276, -118.027491).[27] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.6 square miles (25 km2), of which 9.6 square miles (25 km2) of it is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) of it (0.89%) is water.

Climate

editEl Monte has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa).

| Climate data for El Monte, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

68 (20) |

70 (21) |

73 (23) |

76 (24) |

80 (27) |

85 (29) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

79 (26) |

73 (23) |

67 (19) |

76 (24) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 45 (7) |

47 (8) |

50 (10) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

61 (16) |

65 (18) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

57 (14) |

49 (9) |

44 (7) |

55 (13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.68 (93) |

4.66 (118) |

3.00 (76) |

1.10 (28) |

.38 (9.7) |

.15 (3.8) |

.04 (1.0) |

.07 (1.8) |

.33 (8.4) |

.78 (20) |

1.45 (37) |

2.42 (61) |

18.06 (459) |

| Source: [28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 1,283 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,479 | 171.2% | |

| 1940 | 4,746 | 36.4% | |

| 1950 | 8,101 | 70.7% | |

| 1960 | 13,163 | 62.5% | |

| 1970 | 69,892 | 431.0% | |

| 1980 | 79,494 | 13.7% | |

| 1990 | 106,209 | 33.6% | |

| 2000 | 115,965 | 9.2% | |

| 2010 | 113,475 | −2.1% | |

| 2020 | 109,450 | −3.5% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 106,907 | −2.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] | |||

The population has increased by more than 40% since the 1970s, with homes replacing the walnut groves for which the city was known. There is historically a large Mexican and Latino community in El Monte.[30]

2020

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[31] | Pop 2010[32] | Pop 2020[33] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 8,542 | 5,556 | 3,667 | 7.37% | 4.90% | 3.35% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 640 | 502 | 745 | 0.55% | 0.44% | 0.68% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 331 | 133 | 146 | 0.29% | 0.12% | 0.13% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 21,315 | 28,264 | 32,940 | 18.38% | 24.91% | 30.10% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 90 | 84 | 34 | 0.08% | 0.07% | 0.03% |

| Other Race alone (NH) | 107 | 116 | 356 | 0.09% | 0.10% | 0.33% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 995 | 503 | 743 | 0.86% | 0.44% | 0.68% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 83,945 | 78,317 | 70,819 | 72.39% | 69.02% | 64.70% |

| Total | 115,965 | 113,475 | 109,450 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010

editThe 2010 United States Census[34] reported that El Monte had a population of 113,475. The population density was 11,761.6 inhabitants per square mile (4,541.2/km2). The racial makeup of El Monte was 44,058 (38.8%) White (4.9% Non-Hispanic White),[7] 870 (0.8%) African American, 1,083 (1.0%) Native American, 28,503 (25.1%) Asian (13.5% Chinese, 7.4% Vietnamese, 1.2% Filipino, 0.4% Cambodian, 0.2% Burmese, 0.2% Japanese, 0.2% Korean, 0.2% Indian, 0.2% Thai), 131 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 35,205 (31.0%) from other races, and 3,625 (3.2%) from two or more races. 78,317 (69.0%) of the population is Hispanic or Latino of any race (60.9% Mexican, 2.3% Salvadoran, 1.2% Guatemalan, 0.4% Nicaraguan, 0.3% Honduran, 0.3% Cuban, 0.2% Puerto Rican, and 0.2% Peruvian).

The Census reported that 112,395 people (99.0% of the population) lived in households, 317 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 763 (0.7%) were institutionalized.

There were 27,814 households, out of which 14,557 (52.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 15,087 (54.2%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 5,298 (19.0%) had a female householder with no husband present, 2,962 (10.6%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 2,061 (7.4%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 161 (0.6%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 3,130 households (11.3%) were made up of individuals, and 1,539 (5.5%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.04. There were 23,347 families (83.9% of all households); the average family size was 4.23.

The population was spread out, with 32,234 people (28.4%) under the age of 18, 12,814 people (11.3%) aged 18 to 24, 33,263 people (29.3%) aged 25 to 44, 24,567 people (21.6%) aged 45 to 64, and 10,597 people (9.3%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 99.4 males.

There were 29,069 housing units at an average density of 3,013.0 per square mile (1,163.3/km2), of which 11,740 (42.2%) were owner-occupied, and 16,074 (57.8%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.4%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.6%. 46,802 people (41.2% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 65,593 people (57.8%) lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2010 United States Census, El Monte had a median household income of $39,535, with 24.3% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[7]

2000

editAs of the census[35] of 2000, there were 115,965 people, 27,034 households, and 23,005 families residing in the city. The population density was 12,139.5 inhabitants per square mile (4,687.1/km2). There were 27,758 housing units at an average density of 2,905.8 per square mile (1,121.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 72.39% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race, 35.67% White, 4.9% White Persons not Hispanic,[7] 0.77% Black or African American, 1.38% Native American, 18.51% Asian, 0.12% Pacific Islander, 39.27% from other races, and 4.29% from two or more races. Mexican and Chinese were the most common ancestries.[36]

There were 27,034 households, out of which 53.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.0% were married couples living together, 18.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 14.9% were non-families. 10.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 4.24 and the average family size was 4.43.

In the city, the population were 34.1% under the age of 18, 12.1% from 18 to 24, 31.5% from 25 to 44, 15.4% from 45 to 64, and 6.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,439, and the median income for a family was $32,402. Males had a median income of $21,789 versus $19,818 for females. The per capita income for the city was $10,316. About 22.5% of families and 26.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.9% of those under age 18 and 13.3% of those age 65 or over.

Mexican (62.0%) and Chinese (10.1%) were the most common ancestries. Mexico (63.6%) and Vietnam (13.5%) were the most common foreign places of birth.[37]

Homelessness

editIn 2022, Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority's Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count counted 230 homeless individuals in El Monte.[38]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 160 | — |

| 2017 | 240 | +50.0% |

| 2018 | 517 | +115.4% |

| 2019 | 428 | −17.2% |

| 2020 | 433 | +1.2% |

| 2022 | 230 | −46.9% |

| Source: Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority | ||

Government

editMunicipal government

editThe El Monte City Council has seven members—an elected Mayor and six council members elected by districts. The Mayor and City Council are elected by the voters of El Monte and are responsible for overseeing the delivery of local government services to the residents of the city.

| Office | Office Holder | Term Ends |

|---|---|---|

| Mayor | Jessica Ancona | December 2024 |

| Councilmember | Julia Ruedas | December 2026 |

| Councilmember | Victoria Martinez-Muela | December 2024 |

| Mayor Pro-Tem | Martin Herrera | December 2026 |

| Councilmember | Alma D. Puente | December 2024 |

| Councilmember | Richard J. Rojo | December 2026 |

| Councilmember | Marisol Cortez | December 2026 |

The city manager is Alma Martinez.[40]

State and federal representation

editIn the California State Senate, El Monte is in the 22nd Senate District, represented by Democrat Susan Rubio.[41] In the California State Assembly, it is split between the 48th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Blanca Rubio, and the 49th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Mike Fong.[42]

In the United States House of Representatives, El Monte is in California's 31st congressional district, represented by Democrat Grace Napolitano.[43]

Public safety

editThe City of El Monte has its own police department[44] and contracts with the Los Angeles County Fire Department for fire services and emergency medical response.

The El Monte Police Department consists of 117 sworn police officers who provide emergency services to the citizens of El Monte. The current Chief of Police is Jake Fisher

The City of El Monte Neighborhood Services Division provides enforcement of health and safety, municipal codes, zoning and building codes. Five Neighborhood Services Officers respond to complaints and pro-actively address violations. The Animal Control Division is also part of the Neighborhood Services Division. Animal Control Officers respond to all calls related to animals.

Economy

editAccording to the city's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[45] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | El Monte City Elementary School District | 1,500 |

| 2 | El Monte Union High School District | 1,400 |

| 3 | Mountain View Elementary School District | 1,000 |

| 4 | Longo Toyota-Lexus | 831 |

| 5 | City of El Monte | 505 |

| 6 | McGill Corporation | 475 |

| 7 | Staffing Solutions | 266 |

| 8 | Asian Pacific Health Care Venture | 260 |

| 9 | The Home Depot | 251 |

| 10 | Sam's Club | 203 |

[46] Cathay Bank has a corporate center in El Monte.[47] https://www.ci.el-monte.ca.us/DocumentCenter/View/3679/City-of-El-Monte-CAFR-2019-FINAL-PDF

Education

editThe El Monte Union High School District consists of the following schools:

- Arroyo High School

- El Monte High School

- Mountain View High School

- South El Monte High School

- Fernando R. Ledesma High School, Formerly known as Valle Lindo Continuation School

- Rosemead High School

- El Monte-Rosemead Adult School

The El Monte City School District contains 17 elementary schools:[48] one serving grades K-4, one serving grades K-5, ten serving grades K-6, and six serving grades K-8. The district also administers four Head Start (preschool) sites, which are located at the elementary schools.

- Cherrylee Elementary School[49]

- Columbia Elementary School[50]

- Cortada Elementary School[51]

- Durfee Elementary School[52]

- Gidley Elementary School[53]

- Legore Elementary School[54]

- Mulhall Elementary School

- New Lexington Elementary School

- Norwood Elementary School

- Potrero Elementary School

- Rio Vista Elementary School

- Shirpser Elementary School

- Thompson, (Byron E.) Elementary School[55]

- Wilkerson Elementary School

- Wright Elementary School

- Cleminson Elementary School [56]

- Rio Hondo Elementary School

The Mountain View School District[57] is a K-8 school district comprising ten elementary schools, one intermediate school, one middle school, an alternative education program for students in grades 5–8, and a Children's Center and Head Start/ State Preschool program. The district has an enrollment of 8,600 students.

- Baker Elementary School

- Children's Center/Head Start/State Preschool

- Cogswell Elementary School

- Kranz Intermediate School

- La Primaria Elementary School

- Madrid Middle School

- Magnolia Learning Center

- Maxson Elementary School

- Miramonte Elementary School

- Monte Vista Elementary School

- Parkview Elementary School

- Payne Elementary School

- Twin Lakes Elementary School

- Voorhis Elementary School

Transportation

editEl Monte is served by Metro, Foothill Transit, and the city-operated El Monte Transit. Metro's J Line ends at El Monte Station. Train service to El Monte is provided by Metrolink's San Bernardino Line, which stops at the El Monte station. Interstate 10 traverses El Monte. San Gabriel Valley Airport, a general aviation airport, is located in El Monte.

Health services

editThe Los Angeles County Department of Health Services operates the Monrovia Health Center in Monrovia, serving El Monte.[58] The El Monte Comprehensive Health and Mammography Center is located on Ramona Blvd. in El Monte. It offers medical and dental services for low-income individuals, but is not an emergency center.[59]

Media

editEl Monte community news is provided by the San Gabriel Valley Tribune which is published daily. Other local newspapers include Mid-Valley News and El Monte Examiner which are both published weekly.[60][61][62]

In popular culture

editEl Monte is credited with being the birthplace of TV variety shows. Hometown Jamboree, a KTLA-TV Los Angeles-based show, was produced at El Monte Legion Stadium in the 1950s.[63] The Saturday night stage show was hosted and produced by Cliffie Stone, who helped popularize country music in California.[64]

In the 1950s, as the unstable racial climate and the hostility toward rock & roll started to emerge, rock & roll shows were forced from the City of Los Angeles by police pressure. The El Monte Legion Stadium, outside the city limits, became the site of a series for rock and roll concerts by Johnny Otis and other performers. (Johnny Otis along with Alan Freed and Dick Clark were the major powers in the growing rock and roll industry.) During the fifties, teenagers from all over Southern California flocked to El Monte Legion Stadium every Friday and Saturday night to see their favorite performers. Famous singers who performed there include: Ritchie Valens, Rosie & the Originals, Brenton Wood, Earth, Wind & Fire, The Grateful Dead,[65] Dick Dale and his Del-Tones and Johnny "Guitar" Watson. Disc jockeys Art Laboe and Huggy Boy enhanced the stadium's popularity with their highly publicized Friday Night Dances with many popular record artists of the late 1950s and 1960s. "El Monte Legion Stadium", as it was often called, was the "Happening" place to be for the teenagers of that era.[66] In a closed-circuit telecast, a recorded performance of The Beatles, the Beach Boys, and Lesly Gore aired in the El Monte Legion Stadium from Mar 14–15, 1964.[67]

El Monte is known for the long-time rock & roll hit "Memories of El Monte",[68] written by Frank Zappa and originally recorded by The Penguins, one of the local Doo-wop groups from the 1950s that became famous nationwide. The song is in remembrance of The El Monte Legion Stadium and can be heard on many albums including Art Laboe's Memories of El Monte. Although the stadium closed their doors nearly 50 years ago, the music continues to live on.[69] El Monte was the birthplace of singer–guitarist Mary Ford, of Les Paul and Mary Ford fame. John Larkin, known as (Scatman John), is also a native. El Monte was home to musicians Gregg Myers and Joe McDonald, who performed in the 1960s with Country Joe and the Fish.

A popular attraction from 1925 to 1942 was Gay's Lion Farm. Two European retired circus stars, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gay, operated this tourist attraction, which has been called "the Disneyland of the 1920s and 1930s" by historian Jack Barton,[10] and many others of that era. The Gays raised wild animals for use in the motion picture industry and housed over 200 African lions. Many of the lions starred in films during the 1920s and 1930s, including the Tarzan films starring Elmo Lincoln and Johnny Weissmuller. The Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion logo was made with two lions from the farm, "Slats" (1924–1927), and his lookalike successor "Jackie" (1928-1956). Another one of the farm's famous lions was Numa, who appeared in several films throughout the 1920s, including Charlie Chaplin's "The Circus."[70] In 1925, El Monte Union High School adopted "The Lions" name for its teams, and the Gays provided a lion mascot for big games. The famous live lion farm was closed temporarily due to wartime meat shortages. It never reopened, but a life-sized memorial statue can be seen next to I-10 on the SE corner of Valley Boulevard and Peck Road. The original lion statue, commissioned for the Farm, stands in front of nearby El Monte High School.[71]

Horse racing's most famous jockey, Willie Shoemaker, was a resident and attended El Monte High School, until he dropped out to work in the nearby stables.[72] El Monte was also briefly the home to author James Ellroy until his mother Geneva was murdered there in 1958.[73] Former baseball player Fred Lynn was a resident of El Monte. Actor-filmmaker Timothy Carey filmed much of his underground feature The World's Greatest Sinner (1962) in El Monte. Modern authors Salvador Plascencia, 33, and Michael Jaime-Becerra, 36, both grew up in El Monte and each references El Monte in his novels.[74] Mister Ed, the palomino of the classic 1960s television show, was foaled in 1949 in El Monte and named "Bamboo Harvester".[75]

Notable people

edit- Cris Abrego, television producer

- Art Acevedo, police officer

- Rob Bottin, special make-up effects creator

- A.L.T., Chicano rapper

- Timothy Carey, film and television actor

- Glenn Corbett, actor

- Mack Ray Edwards, child sex abuser and serial killer

- James Ellroy, author

- Mary Ford, vocalist and guitar player

- Virginia Gilmore, actress

- Alexandra Hay, actress

- Roger Hernández, politician

- Cathy LeFrançois, IFBB professional bodybuilder

- Country Joe McDonald, lead singer for the band Country Joe & the Fish

- Tom Morgan, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Lorenzo Oatman and sister Olive Oatman, survivors of the Oatman Massacre of 1851 in Arizona

- Steven Parent, aka "Stereo Steve", victim of the Charles Manson murders[76]

- Bill Piercy, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Salvador Plascencia, author

- Kim Rhode, Olympic shooter

- Emily Rios, actress (Breaking Bad)

- Scatman John, musician

- Willie Shoemaker, jockey

- Robert P. Shuler, reformer and minister of Trinity Methodist Church, Los Angeles

- Hilda Solis, politician

Sister cities

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Government: Council Members". City of El Monte. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "City Manager's Office". City of El Monte. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "Treasury". City of El Monte. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "El Monte". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "El Monte (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "City Clerk's Office". City of El Monte. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 118.

- ^ a b c "A Brief History Of El Monte". Home.earthlink.net. Archived from the original on August 1, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "City of El Monte" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 30, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- ^ Barton, Jorane King (October 18, 2006). El Monte. Arcadia Publishing Library Editions. ISBN 9781531628284.

- ^ a b c "El Monte CA | History - Presented by Village Profile". Villageprofile.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "Monte Rangers". Militarymuseum.org. February 8, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Clendenen, Clarence C. (December 1961). "Dan Showalter: California Secessionist". California Historical Society Quarterly. 40 (4): 309–325. doi:10.2307/25155429. JSTOR 25155429.

- ^ "Historic California Posts: Camp Carleton (Camp Banning, Camp Prentis, New Camp Carleton)". Militarymuseum.org. February 8, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Paul R. Spitzzeri (Fall 2007). "What a Difference a Decade Makes: Ethnic and Racial Demographic Change in Los Angeles County during the 1860s" (PDF). Branding Iron.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau. "Population of the United States in 1860: California" (PDF).

- ^ Related Articles. "Gay's Lion Farm (farm, El Monte, California, United States) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "ブリタニカ・ジャパン - Encyclopædia Britannica A-Z Browse". Britannica.co.jp. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Time, San Gabriel Valley in. "Dorothea Lange Was in El Monte Before Taking "The Migrant Mother"". San Gabriel Valley in Time. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Tokunaga, Yu (April 3, 2020). "Japanese Farmers, Mexican Workers, and the Making of Transpacific Borderlands". Pacific Historical Review. 89 (2): 166–167. doi:10.1525/phr.2020.89.2.165. ISSN 0030-8684.

- ^ Shyong, Frank (December 13, 2014) "San Gabriel Valley's El Monte getting a boost from Chinese investors" Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Los Angeles". Ohp.parks.ca.gov. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ Lacher, Irene. "El Monte Historical Society Museum - El Monte, CA 91731 | Find Local Los Angeles". Findlocal.latimes.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "Census snapshot: Asians find homes in historically Latino El Monte" (Archive). Los Angeles Times. December 8, 2008. Retrieved on January 8, 2016.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Average weather for El Monte". Weather.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Race, Place, and Reform in Mexican Los Angeles: A Transnational Perspective, 1890-1940.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – El Monte city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – El Monte city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – El Monte city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - El Monte city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ El Monte Profile - Mapping LA - Los Angeles Times

- ^ "El Monte".

- ^ "Homeless Count by City/Community". LAHSA. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "City Council | El Monte, CA". www.ci.el-monte.ca.us. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ "City of EL Monte > Home". Ci.el-monte.ca.us. Archived from the original on March 25, 2004. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Communities of Interest — City". California Citizens Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on October 23, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "California's 31st Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ EMPD Official Website retrieved June 20, 2012

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the year ended June 30, 2018". City of El Monte. June 30, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ City of El Monte CAFR FY 2019

- ^ "2014 Annual Report 2014" (Archive). Cathay Bank. Retrieved on March 27, 2016. p. 18. "Corporate Center 9650 Flair Dr. El Monte, CA 91731"

- ^ "Best Schools in El Monte City". SchoolDigger.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "School Information & Ratings on SchoolFinder". Education.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Cleminson Elementary School in Temple City, CA". Education.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "Mountain View School District". Mtviewschools.com. December 31, 1999. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "Monrovia Health Center." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved on March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Los Angeles County Health Service in El Monte | Los Angeles County Health Service 10953 Ramona Blvd, El Monte, CA 91731 Yahoo - US Local". Local.yahoo.com. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "What is Digital First Media and the Southern California News Group who just purchased the Orange County Register?". San Bernardino Sun. March 21, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Humanities, National Endowment for the. "Mid valley news". Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Weekly Newspapers – El Monte Examiner – CNPA". cnpa.com. September 27, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Full List of Inductees". Country Music Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on July 21, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ Nelson, Valerie J. (February 11, 2009). "Molly Bee dies at 69; country singer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Live at Legion Stadium on 1970-12-26 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". December 26, 1970. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "History-Making Oldies Cruise Announced - Doo Wop Cruise, Doo-Wop, Oldies Cruises". Free-press-release.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ San Gabriel Valley in Time. "When The Beatles Kinda Played at the El Monte Legion Stadium". San Gabriel Valley in Time. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "Audio soundbyte". Foreveroldies.com. Archived from the original (MP3) on October 28, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Even though the stadium closed their doors almost fifty years ago, the music and the memories, continues to live on.

- ^ "The 117th Conference & Equipment Exhibit: Century Plaza Hotel, Los Angeles September 28–October 3, 1975". Journal of the SMPTE. 84 (8): 627–646. 1975. doi:10.5594/j13324. ISSN 0361-4573.

- ^ John Garside & Marty Shields. Gay's Lion Farm - A Forgotten Tale of El Monte. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=47do8uEihH8

- ^ "Willie Shoemaker Facts". Yourdictionary.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Memories in black". Ocregister.com. September 15, 2006. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Reed (April 25, 2010). "Writers Salvador Plascencia and Michael Jaime-Becerra share a city and common inspiration: El Monte". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "mr ed story". Angelfire.com. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ "Steven Parent". CieloDrive.com. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ Mexican sister city gifts El Monte with centennial mural