Mark of Ephesus (Greek: Μάρκος ὁ Ἐφέσιος, born Manuel Eugenikos) was a hesychast theologian of the late Palaiologan period of the Byzantine Empire who became famous for his rejection of the Council of Ferrara–Florence (1438–1439). As a monk in Constantinople, Mark was a prolific hymnographer[1] and a follower of Gregory Palamas' theological views. As a theologian and a scholar, he was instrumental in the preparations for the Council of Ferrara–Florence, and as Metropolitan of Ephesus and delegate for the Patriarch of Alexandria, he was one of the most important voices at the synod. After renouncing the council as a lost cause, Mark became the leader of the Orthodox opposition to the Union of Florence, thus sealing his reputation as a defender of Eastern Orthodoxy and pillar of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Mark of Ephesus | |

|---|---|

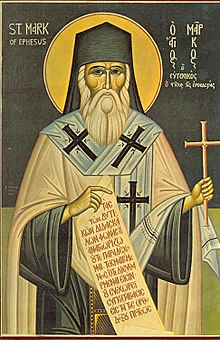

Icon of Saint Mark of Ephesus | |

| Defender and Pillar of Orthodoxy Archbishop of Ephesus | |

| Born | c. 1392 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | June 23, 1444 (age 52) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 1734, Constantinople by Patriarch Seraphim of Constantinople |

| Major shrine | Monastery of Saint Lazarus, Galata modern day Karaköy, Turkey |

| Feast | 19 January |

| Attributes | Long white beard, vested as a bishop, holding a scroll in one hand and cross in the other |

Early life

editMark was born Manuel in 1392 in Constantinople to George, sakellarios of Hagia Sophia, an Orthodox deacon, and Maria, the daughter of a devout doctor named Luke. Mark learned how to read and write from his father, who died while Mark and his younger brother John Eugenikos were still children. Maria had Mark continue his education under John Chortasmenos, who later became Metropolitan Ignatius of Selymbria, and a mathematician and philosopher by the name of Gemistus Pletho.

Activity at the Council of Florence and aftermath

editSt Mark of Ephesus was one of the Eastern bishops who refused to sign the agreement with the Roman Church concerning the addition of the Filioque clause during the Council of Ferrara–Florence, however, was cordial in dialogues with the Catholics. He held that the Latin Church continued in both heresy and schism. Due to this, he has been referred to as one of the Pillars of Orthodoxy — alongside St Photios & St Gregorios Palamas. He also rejected the doctrine of Purgatory, in that he objected to the existence of a purgatorial fire that purified the souls of the faithful of their imperfections before reception of the Beatific Vision.

Death

editHe died peacefully at the age of 52 on June 23, 1444, after an excruciating two-week battle with intestinal illness. On his death bed, Mark implored Georgios Scholarios, his former pupil, who later became Patriarch Gennadius of Constantinople, to be careful of involvement with Western Christendom and to defend Orthodoxy. According to his brother John, his last words were "Jesus Christ, Son of the Living God, into Thy hands I commit my spirit." Mark was buried in the Mangana Monastery in Constantinople.

Posthumous miracle and canonization

editThe Eugenikos family celebrated each anniversary of Mark's death with a eulogy consisting of a service (akolouthia) and synaxarion of a short life of Mark. Thanks in large part to Patriarch Gennadius Scholarius, veneration of Mark spread among the church. In 1734 Patriarch Seraphim of Constantinople presided over the Holy Synod of the Church of Constantinople and solemnly glorified (canonized) Mark and added six services to the two older ones.

There is an account of a posthumous miracle performed by Mark of Ephesus. Doctors gave up on trying to save the life of the terminally ill sister of Demetrios Zourbaios, after their efforts had worsened her condition. After losing consciousness for three days she suddenly woke up, to the delight of her brother, who asked her why she woke up drenched in water. She related that a bishop escorted her to a fountain and washed her and told her, "Return now; you no longer have any illness." She asked him who he was and he informed her, "I am the Metropolitan of Ephesus, Mark Eugenikos." After being miraculously healed, she made an icon of Saint Mark and lived devoutly for another 15 years.

Legacy

editThe Orthodox Church considers Mark of Ephesus a saint, calling him, together with Photius the Great and Gregory Palamas, a Pillar of Orthodoxy. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain, in his service to the saint, called him "the Atlas of Orthodoxy." His feast day is January 19, the day his relics were moved to the monastery of Lazarus in Galata.

Theology

editMark's theological output was extensive and covered a wide range of genres and topics typical of monastic writers.

Hymnography

editMark composed a wealth of poetic texts honoring God and the saints, many of which were intended for use in a liturgical setting. In addition to canons and services to Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, and the angels, Mark honored his favorite Fathers of the Church: Gregory Palamas, John Damascene, Symeon Metaphrastes, along with a wealth of more ancient saints. Additionally, Mark composed verses celebrating the lives and achievements of his heroes, such as Joseph Bryennios.[2]

Hesychasm

editMark was a devoted disciple of Gregory Palamas. Throughout his life he composed several treatises in defense of the essence–energies distinction, and he defended the unique contributions of Hesychast theology in the face of charges of innovation.

Dogmatic/polemical theology

editOne of Mark's most important theological contributions was his opposition to the Roman Catholic Filioque. At the Council of Florence, the examination of this controversy had both text-critical and exegetical dimensions, as the participants debated the authenticity of sources, the precision of grammatical constructions, and the canon of authoritative patristic texts. Mark had played an early role in the gathering of manuscripts, and his contested readings at the synod have since been vindicated for their precision and accuracy.[3]

During The council of florence Mark made strong arguments against the latin use of the word Filloque. Echoing centuries of polemic, going back to Photius, the debates surrounding the Filioque admitted resonances of more recent discussions, such as those of John Bekkos and Gregory of Cyprus. In the end, Mark could not concede that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Son as well as the Father, even by using the Orthodox phrase of "through the Son," since Mark considered this to be an equivocation in light of the obvious theological disagreements between East and West. For Eugenikos, the Holy Spirit proceeds only from the Father, and the phrase "through the Son" did not express anything like the theology of the Filioque.

Anthropology

editMark's criticism of the doctrine of Purgatory, the other major topic at Florence, involved him in questions relating to the nature of the human composite. Basing himself on Palamite conceptions of man, Mark articulated a theory of the human person rooted in Christology and Orthodox doctrines of Creation. Mark's discourses at Florence are, in this regard, supplemented by writings which he produced in response to the Platonism of Gemisthus Plethon, who preached a radical identification of the human person with the soul, to the detriment of embodied life.[4]

Latin influences

editThe Palaiologan period in which Mark lived witnessed the translation of the works of Thomas Aquinas into Greek, an event whose repercussions have yet to be fully documented and expounded. In spite of remaining ambiguities, though, it has become increasingly clear that the Hesychasts were not unaware of Latin theology.

Some scholars have hypothesized that Mark adopts Thomas Aquinas' hylomorphism in his defense of the Resurrection, and that he experiments with arguments from Thomas Aquinas' Summa contra Gentiles in order to argue for the concomitance of mercy in God's condemnation of unrepentant sinners to hell. "Further, Eugenicus’ treatise Peri anastaseôs (ed. A. SCHMEMANN, “Une œuvre inédite de St Marc d’Éphèse: Peri anastaseôs”, in: Theología 22 (1951): 51–64; text on pp. 53–60) is merely a defence of the rational possibility of the doctrine of resurrection and a rational refutation of some philosophical objections against it based almost entirely on Thomas Aquinas’ description of the natural unity of the human soul with the body in explicitly hylomorphic and anti-Platonic terms (see Summa contra Gentiles IV,79-81; cf. Vat. gr. 616, ff. 289r-294v)."[5] Also, eminent Eastern Orthodox scholars have already suggested that, during Mark's courteous and apologetic period of preparation for the Council of Florence, the Ephesine explicitly omitted condemnations of Aquinas by name, even if his two "Antirrhetics against Manuel Kalekas" contained condemnation of Thomistic Trinitarian theology, especially Thomas' implicit rejection of the essence–energies distinction and the Thomas' assertion that Aristotelean "habits" were very similar to the charisms or the Holy Spirit (e.g., Faith, Hope, & Charity).[6] What is more, Mark had a great love for Augustine of Hippo, spending money at Florence to buy manuscripts of the same. In fact, at Florence he copiously cites Augustinian and Ps.-Augustinian works approvingly as an authority in favor of the Eastern Orthodox position.[7] Finally, Mark was savvy enough to understand Bernard of Clairvaux's writings from an unknown translation (likely through his former pupil Scholarius). He used Bernard to argue for the Palamite position on the beatific vision.[8] In effect, Mark of Ephesus' liberal use of Latin authorities paved the way for the fuller synthesis of his pupil Gennadius Scholarius after his master's death.[9]

Even if Mark was initially zealous for the "divine work of union" (τὸ θεῖον ἔργον τῆς εἰρήνης καὶ ἑνώσεως τῶν ἐκκλησιῶν)[10] in his opening speech to Pope Eugene IV, Mark was disgusted at the Latin efforts and plots to prevent him from reading the acts of the Ecumenical Councils aloud, wherein the canons prohibited additions to the Nicene Creed. The Latins and Greeks had different opinions over what was more important to address first. That is, the addition to the creed and the orthodoxy of the filioque clause itself. Mark Eugenikos and the Greeks leaning to the former (although Bessarion of Nicaea had reservations about this and preferred to debate the dogma itself so as to avoid the Greek party becoming dispirited in the event the Latins emerge victorious in a debate over the addition to the creed) and Latins preferring a debate over the orthodoxy of the clause itself deeming that should the orthodoxy of the filioque be demonstrated, the Greeks would have no credible reason to oppose its inclusion in the creed.

At the beginning of the council, in the same opening speech, Mark noted that two issues alone were necessary to overcome the historical divisions between the Latin and Greek Churches; namely, (1.) The issue of the Filioque or Latins' assertion that the Father and the Son are conjointly a cause of the Holy Spirit, and (2.) the issue of unleavened bread, whereby the Latins were judged to have historically abandoned the orthodox (vs. Armenian) practice of using leavened bread for the sake of azymes. Because Mark found reasons to reject uniquely Latin authorities, councils, and texts unavailable in Greek or unapproved by jointly canonical synods, he became increasingly exasperated at Latin attempts to introduce a host of new authorities into the debates that turned out to be spurious. A charge he had because of the Latins frequent (although innocent) use of such documents. In the end, Mark refused to sign the council documents following a debate with John of Montenero, who claimed that there was a difference in the dignity of persons in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This had the effect of convincing Mark that the Thomists were subordinationists since Montenero was willing to defend a distinction in the persons according to "dignity" (dignitas or axiôma).[11]

Unsurprisingly, Mark concentrated on anti-Latin propaganda by recourse to differences that were most obvious to the simple Greek populace. For example, he noted that the Latins had no throne reserved for their hierarch in the sanctuary, the Latin priests shaved their faces "like women celebrating Mass," and various other minutiae.[12] In this, Mark did not ignore various abstractions of metaphysics, yet he was more realistic and practical in his apologetics and an excellent propagandist. Therefore, one must read Mark's post-Florentine and anti-Latin propaganda through the optic of Mark's ends. Even if Mark dissented from Florence for traditional, theological motives he was quick to cite practical differences that emphasized the gulf between Latins and Greeks.

Hymns

editApolytikion (Tone 4)

- By your profession of faith, O all-praised Mark

- The Church has found you to be a zealot for truth.

- You fought for the teaching of the Fathers;

- You cast down the darkness of boastful pride.

- Intercede with Christ God to grant forgiveness to those who honor you!

Kontakion (Tone 3)

- Clothed with invincible armor, O blessed one,

- You cast down rebellious pride,

- You served as the instrument of the Comforter,

- And shone forth as the champion of Orthodoxy.

- Therefore we cry to you: "Rejoice, Mark, the boast of the Orthodox!"

Quotes

edit- "It is impossible to recall peace without dissolving the cause of the schism— the primacy of the Pope exalting himself equal to God."

- "The Latins are not only schismatics but heretics... we did not separate from them for any other reason other than the fact that they are heretics. This is precisely why we must not unite with them unless they dismiss the addition from the Creed filioque and confess the Creed as we do."

- "Our Head, Christ our God... does not tolerate that the bond of love be taken from us entirely."[13]

- "We seek and we pray for our return to that time when, being united, we spoke the same things and there was no schism between us."[14]

References

edit- ^ Mineva, Evelina (2000). The Hymnographic Opus of Mark Eugenikos (in Greek). Athens.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Constas, Nicholas (2002). "Mark Eugenikos". Brepols: Corpus Christianorum. pp. 429–432.

- ^ Alexakis, Alexandros (1996). Codex Parisinus Graecus 1115 and its Archetype. Dumbarton Oaks.

- ^ Constas, Nichols (2002). "Mark Eugenikos," in ed. Conticello, La Theologie Byzantine II. Brepols: Corpus Christianorum. pp. 452–459.

- ^ See J.A. Demetracopoulos, “Palamas Transformed: Palamite Interpretations of the Distinction between God’s ‘Essence’ and ‘Energies’ in Late Byzantium,” in Greeks, Latins, and Intellectual History 1204-1500, ed. M. Hinterberger and C. Schabel (Paris: Peeters Leuven, 2011), 369.http://www.elemedu.upatras.gr/english/images/jdimitrako/Palamas_Transformed_Demetracopoulos.pdf

- ^ See Pilavakis, Introduction to “First Antirrhetic,” 149 (infra). Mark condemns thomistic metaphysics in Mark Eugenicus, “Second Antirrhetic against Manuel Kalekas. Editio princeps, ed. M. Pilavakis (forthcoming PhD diss., Athens, 2014), 53.

- ^ Demacopoulos, George E.; Papanikolaou, Aristotle (2008). Orthodox Readings of Augustine. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-327-4.

- ^ Kappes, Christiaan (2013-01-01). ""Provisional Definition of Byzantine Theology contra Pillars of Orthodoxy?"". Nicolaus 40.

- ^ Kappes, “A Provisional Definition of Byzantine Theology,” 193-196

- ^ Quae supersunt Actorum Graecorum Concilii Florentini. Concilium Florentinum Documenta et Scriptores Series B, vol. 5, books 1-2, ed. J. Gill (Rome: PIOS, 1953), 1: 49 (aka, Acta Graeca)

- ^ see: J.L. van Dieten, “Zur Diskussion des Filioque auf dem Konzil von Florenz,” Byzantina Symmeikta 16 (2008): 280-282.

- ^ A. Chrysoberges, Testimonium ineditum Andreae Archiepiscopi Rhodi de Marco Eugenico, ed. G. Hoffman, Acta Academiae Velebradensis 13 (1937) 19-23

- ^ "Address by the Archbishop of Athens and all Greece Christodoulos to Pope John Paul II of Rome". www.orthodoxresearchinstitute.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Address by the Archbishop of Athens and all Greece Christodoulos to Pope John Paul II of Rome". www.orthodoxresearchinstitute.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

Mineva, Evelina, "The hymnographic works of Mark Eygenikos", Athens: Kanaki publ. 2004 (in Greek).

External links

edit- St Mark of Ephesus Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion (January 19)

- St. Mark of Ephesus and the False Union of Florence

- St. Mark of Ephesus: A True Ecumenist

- Address of St. Mark of Ephesus on the Day of His Death

- The Encyclical Letter of St. Mark of Ephesus

- Saint Mark Eugenikos (the Courteous) Archived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Migne’s Patrologia Graeca volume 160 containing the works of Mark of Ephesus

- St. Mark of Ephesus

- [1]

- [2]

- [3]