Marshall County is a county in the U.S. state of West Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 30,591.[1] Its county seat is Moundsville.[2] With its southern border at what would be a continuation of the Mason-Dixon line to the Ohio River, it forms the base of the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia.

Marshall County | |

|---|---|

Marshall County Courthouse | |

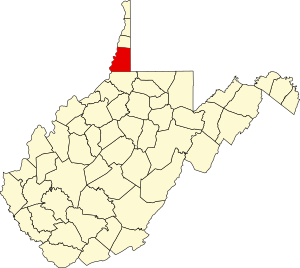

Location within the U.S. state of West Virginia | |

West Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 39°52′N 80°40′W / 39.87°N 80.67°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | March 12, 1835 |

| Seat | Moundsville |

| Largest city | Moundsville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 312 sq mi (810 km2) |

| • Land | 305 sq mi (790 km2) |

| • Water | 6.7 sq mi (17 km2) 2.2% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 30,591 |

| • Estimate (2021) | 30,115 |

| • Density | 98/sq mi (38/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

Marshall County is part of the Wheeling metropolitan area.

Marshall County is home to the largest conical burial mound in North America, at Moundsville.[3] Marshall County was formed in 1835[4] from Ohio County by act of the Virginia Assembly. In 1852, on Christmas Eve, workers completed the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's connection to the Ohio River at Rosby's Rock in Marshall County.[5] It more recently became home to the New Vrindaban community of Hare Krishnas, and Prabhupada's Palace of Gold.

History

editPrehistory

editNative Americans occupied the area along the narrows of the Ohio River by 250 BCE and the Adena culture constructed the Grave Creek Mound by 100 B.C.E., which was the highest conical burial mound in what came to be the United States, with only that in Miamisburg, Ohio of even comparable size.[6] However, by the 18th century the area contained no permanent settlements. Tribes which hunted, foraged and made war in the area by that time included the Algonquian language speaking Delaware, Ottawa, Miami and Shawnee, and the Iroquoian language speaking Cherokee, Iroquois, Mingo, Mohawk, Wyandot/Huron and Seneca.

Two major trails intersected in what would become Marshall County. One was a major roughly north–south path sometimes known as the Great Indian Warpath (other names included the "Great Catawba War Path", "Cherokee Path" or "Tennessee Path") which ran along the Great Appalachian Valley from what became Olean, New York through Uniontown, Pennsylvania and then split after crossing the Ohio River, such that various branches (in what became West Virginia) reached the Kanawha River or the Cheat River before proceeding southwest to Kentucky and Tennessee, or southeast toward the Carolinas and/or Alabama. Another major trail, more distinct in this area and proceeding east–west, was sometimes known as Braddock's Road or Nemacolin's Path after the native chieftain and trailblazer who assisted General Braddock and George Washington during their unsuccessful march through the Cumberland Narrows pass in the Appalachian Mountains seeking to capture Fort Duquesne in 1755. In 1811 this path was developed through Marshall County into the National Road as discussed below.

Emigration and conflict

editIn 1752, according to Christopher Gist's diary, Gist explored the Ohio River Valley area in what became Marshall County on behalf of the Ohio Company, a group of Virginia investors, before the conflict which became known as the French and Indian War. The French explorer Sieur De la Salle had traveled on the Ohio River in 1669, and Captain deBlainville had buried lead plates staking France's claim to the valley in 1749. English speakers attempted to strengthen their claims initially by settlement, much to the displeasure of local Native Americans. The British government prohibited colonists from officially settling in the area in the 1763 peace treaty following that war.[7]

Nonetheless, emigrants crossed the mountains. John Wetzel staked a claim along Wheeling Creek in what is now Marshall County's Sand Hill District in 1764 (building a fortification by 1769). The British concluded the Treaty of Fort Stanwix with the Iroquois in 1768, which purported to give them this area and much of the Ohio River valley, despite the claims of other native peoples, particularly the Algonquian-speaking tribes. The Zane brothers (Ebenezer, and later Andrew, Jonathan and Silas) built cabins at the confluence of Wheeling Creek and the Ohio River in 1770, and their settlement decades later became Wheeling. Joseph, James and Samuel Tomlinson built a cabin on the Flats of Grave Creek at what became Moundsville around the same time, but experienced "Indian troubles" upon returning the following spring, and despite fortifying it, left until 1773. In 1774, Native Americans decided to drive the settlers from their valley and attacked Michael Cresap's settlement at Cresap's Bottom. The British colonists and military fortified Fort Fincastle at what became Wheeling and which was renamed "Fort Henry" during the American Revolutionary War. Cresap gathered other settlers and counterattacked, continuing what became locally called Cresap's War, or Dunmore's War. In the only pitched battle of that war (considerably downstream of Marshall County), Virginia militia led by colonel Andrew Lewis defeated outnumbered native warriors led by Shawnee Chief Cornstalk at the Battle of Point Pleasant on October 10, 1774.[7]

The large Ohio River valley area which Virginians called the District of West Augusta (the first county organized west of the Appalachian Mountains) sent two delegates to the Virginia convention in 1775, which eventually established the Commonwealth of Virginia. The District was governed from Fort Dunmore (as Virginians renamed it by 1774, and which later became Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). In 1776, the Virginia General Assembly created the counties of Ohio, Monongalia and Yohogania from what had been the District of West Augusta. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania also claimed much of this area, and established Westmoreland County with similar boundaries. Pennsylvania divided the area of Westmoreland County that Virginia considered Yohogania County into Fayette and Washington Counties in 1781 and 1783. It also negotiated its border with Maryland, and only ceded the area south of the Mason–Dixon line to the United States in 1787, when Virginia ceded its claims north of the Ohio River as well, allowing the Continental Congress to establish the Northwest Territory from the area west of both states' reduced claims.

Meanwhile, during the ongoing raids from Native Americans and their British allies, particularly during 1777, many settlers (including in what became Marshall County) left smaller blockhouses and retreated to Fort Redstone at Brownsville, Pennsylvania until the end of the American Revolutionary War.[8] Nonetheless, hostilities continued, as the Wetzel brothers repulsed a raid on Beeler's Station in 1782.[9] In 1784, General George Washington was among the veteran patriots who bought or established land claims in Ohio County (in what later became Marshall County) as the revolutionary war ended. Clark's Fort had been built in 1779 on Wheeling Creek at what became the Pennsylvania/Virginia boundary.[10] Several additional blockhouses and forts were built in 1784, including Baker's Station at Cresap (where the Warrior's Trail reached the Ohio River), and another Clark's Fort at Sherrard (on Wheeling Creek at what became the intersection of routes 88 and 86), and Martin's Fort and Himes Blockhouse where Fish Creek joined the Ohio River. John Wetzel died during a raid on Baker's Station in 1787.[9]

Hostilities with local tribes did not formally end until the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.[11] The following year the Virginia General Assembly split off the northernmost part of Ohio County as Brooke County, but what became Marshall County remained in Ohio County. (Point Pleasant, the location of the critical 1774 battle became a different county's seat when Mason County was split from Kanawha County in 1804.)

Towns, roads and railroads

editThe first town in what became Marshall County, Elizabethtown (which would later become Moundsville), was established in 1798 and named for Joseph Tomlinson's wife. In 1831 a second community, Mound City, was established across Grave Creek, which ultimately joined with the first and jointly became known as Moundsville. A road between Wheeling and Elizabethtown was opened through the efforts of Ohio County officials in 1810. The following year, the U.S. Congress began funding construction of the National Road, running from Cumberland, Maryland across the Appalachian Mountains to Uniontown, Pennsylvania and Washington, Pennsylvania then Wheeling and points westward. The road reached Wheeling (upstream from Elizabethtown) in 1818, and in 1830 Congress authorized rebuilding and improvement of the road using macadam. This led to the establishment of taverns and inns, including in Marshall County, although Wheeling (at the end of the Ohio River narrows as well as where the National Road crossed the Ohio River) would become the only city developed in Ohio County in this era. The National Road received additional impetus when the Wheeling Suspension Bridge across the Ohio River was completed in 1848, although by this time railroad and steamboat technology had improved and superseded the roadway.

The Virginia General Assembly created Marshall County from part of Ohio County on March 12, 1835, the same year Congress gave the National Road (and its maintenance responsibilities) to the states. It was named in honor of John Marshall, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, who died that year.[12] Its local government was organized in June, with its county seat at Elizabethtown. Jacob Burley, Benjamin McMechen, John Parriott, Samuel Howard and Zadock Masters became the new county's first Justices of the Peace, and Elbert H. Caldwell was selected as first Commonwealth attorney.[13] The first courthouse was finished the following year, and replaced in 1875. The building was the seat of county government, and underwent major renovations in 1974.[14]

Agriculture was the main industry during the first decades of Marshall County history, but trade continued along the Ohio River and the National Road. Early businesses included the River Shore Flour Mill (1832) and the Mound City Flour Mill (1845).[14] Marshall County's first newspaper began printing in Elizabethtown in 1831.

An iron forge was established at Benwood near the Ohio river and Wheeling/Ohio County border in 1850, and that industrial area would develop following the Civil War.[15] The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad reached the Ohio River when two construction crews met at Rosbys Rock in Marshall County about five miles from Moundsville on December 24, 1852.[16] In 1857, the railroad first crossed the Ohio river downstream, near Parkersburg. Although both towns and the railroad proposed a bridge linking Benwood and Bellaire, Ohio long before, litigation by the pre-existing ferry company as well as the Civil War discussed below, meant the bridge was not completed until 1870, although refurbished, the B & O Railroad Viaduct remains in use today and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Civil War

editThe Civil War divided Marshall County. Western Virginian Southern Unionists collected in the Wheeling Convention after the Virginia Secession Convention of April 1861. Jacob Burley's son, a farmer and Whig who also served as sheriff and then local Justice of the Peace since 1850, James Burley had been easily elected as Marshall County's delegate at the Secession Convention. His father-in-law was Bushrod W. Price, who had served as delegate in the Virginia General Assembly.[17] Burley voted against secession during both votes, which caused the secessionists to expel him from that convention, but he later won election to the West Virginia Senate in 1863 and 1867.[18] Marshall County's delegates to the Wheeling Convention included Remembrance Swan (whose son Remembrance M. Swan would fight for the Union as an Iowa volunteer),[19][20] C. H. Caldwell and Robert Morris. Ultimately, the Wheeling Convention process led to the creation of the State of West Virginia in 1863.

Meanwhile, James M. Hoge, who had briefly been Elbert Caldwell's successor as the Marshall County commonwealth attorney, but who moved downriver and owned slaves in Putnam County (which sent no delegates to the Wheeling Convention) was elected by Marshall County Confederate troops as Marshall County's delegate in the Virginia General Assembly.

Marshall was one of fifty Virginia counties that were admitted to the Union as the state of West Virginia, at the height of the war on June 20, 1863. Later that year, the counties were divided into civil townships, with the intention of encouraging local government. This proved impractical in the heavily rural state, and the townships would be converted into magisterial districts in 1872.[21] Marshall County was initially divided into nine townships: Cameron, Clay, Franklin, Liberty, Meade, Sand Hill, Union, Washington, and Webster.[22]

Postwar

editIn 1866, after prisoners escaped from local jails, West Virginia's legislature authorized the purchase of land in Moundsville for the new state's penitentiary. The wooden structure was replaced by a gothic-style stone and brick building (West Virginia Penitentiary now operated as a tourist attraction), probably modeled upon a facility opened in 1858 in Joliet, Illinois. It remained West Virginia's maximum security penitentiary from 1876 until 1995 (with a section for female inmates until construction of a separate facility in the 1940s). A more modern set of buildings at the town's outskirts is now the northern regional jail. The Marshall County courthouse was rebuilt in 1876.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had dealt with flooding on the Ohio River as interference to navigation long before the American Civil War, and in 1870 adopted a plan for construction of 13 locks and dams between Pittsburgh and Wheeling, and a few years later Congress authorized funding of a new prototype with adjustable gates near Pittsburgh to secure a 6-foot water flow. As the 20th century began, a series of appropriations funded 18 locks and dams, finally finished in 1929. These were built for flood control, and the canals of 9-foot depth between them facilitated transportation of heavy raw materials (including coal and iron ore) and finished goods (including steel). The McMechen Lockmaster Houses on the Ohio River (built in Marshall County in 1911) are among the few that remain (and have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1992).

In 1872, Marshall County's nine townships were converted into magisterial districts. Their names and boundaries remained largely unchanged, with only minor adjustments over the next century. In the 1970s, Marshall's nine historic districts were consolidated into three new magisterial districts: District 1, District 2, and District 3.[22]

In the late 19th century, several industries, including manufacturers of brooms, buggy whips, bricks, building supplies, steel and glassware developed in Marshall County. In 1892, the Fostoria Glass Company began producing quality tableware in Moundsville (the plant closed in 1986), and in 1901 the United States Stamping Company began producing enameled cooking ware. In the former sheep-farming community of Glen Dale, Wheeling Metal and Manufacturing Company opened a plant in 1904. Industries which developed locally in the early 20th century included: paper box manufacturing, building materials, pottery, well-drilling tools, women's clothing, guns, and chemicals (in World War II). Most of the buildings in the Moundsville Commercial Historic District date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. On April 28, 1924, a mine in Benwood that supplied Wheeling Steel experienced the then-worst mining disaster in West Virginia history, killing an entire shift (119 men; now the state's third worst mining disaster). Between the 1890s and 1941, Benwood, McMechen, and Moundsville were connected by an electric railway. Coal mining remains important in Marshall County, with two mines producing 9.1 million tons of coal in 2009.[23]

In 1924, Marshall County elected the first woman to serve as a West Virginia legislator, Dr. Harriet B. Jones. On August 4, 1927, Charles Lindbergh landed near Moundsville, and by the decade's end the Fokker Aircraft Company established a plant, which became a major employer in the area, and in 1934 was transformed into a toy factory (which closed in 1980).[23] Part of northern Marshall County is now within the city of Wheeling.

In 1968, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada established New Vrindaban near the historic village of Limestone. In 1972, his followers built Prabhupada's Palace of Gold. Both have now become tourist attractions, although New Vrindaban also operates a substantial farm.

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 312 square miles (810 km2), of which 305 square miles (790 km2) is land and 6.7 square miles (17 km2) (2.2%) is water.[24]

Major highways

editAdjacent Counties

edit- Ohio County (north)

- Washington County, Pennsylvania (northeast)

- Greene County, Pennsylvania (east)

- Wetzel County (south)

- Monroe County, Ohio (southwest)

- Belmont County, Ohio (northwest)

National protected area

editDemographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 6,937 | — | |

| 1850 | 10,138 | 46.1% | |

| 1860 | 12,997 | 28.2% | |

| 1870 | 14,941 | 15.0% | |

| 1880 | 18,840 | 26.1% | |

| 1890 | 20,735 | 10.1% | |

| 1900 | 26,444 | 27.5% | |

| 1910 | 32,388 | 22.5% | |

| 1920 | 33,681 | 4.0% | |

| 1930 | 39,831 | 18.3% | |

| 1940 | 40,189 | 0.9% | |

| 1950 | 36,893 | −8.2% | |

| 1960 | 38,041 | 3.1% | |

| 1970 | 37,598 | −1.2% | |

| 1980 | 41,608 | 10.7% | |

| 1990 | 37,356 | −10.2% | |

| 2000 | 35,519 | −4.9% | |

| 2010 | 33,107 | −6.8% | |

| 2020 | 30,591 | −7.6% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 30,115 | [25] | −1.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] 1790–1960[27] 1900–1990[28] 1990–2000[29] 2010–2020[1] | |||

2020 census

editAs of the 2020 United States census, there were 30,591 people and 11,811 households residing in the county. There were 14,728 housing units in Marshall. The racial makeup of the county was 94.1% White, 0.9% African American, 0.4% Asian, 0.1% Native American, 0.4% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 1.2% of the population.

Of the 11,811 households, 50.7% were married couples living together, 28.6% had a female householder with no spouse present, 16.1% had a male householder with no spouse present. The average household and family size was 3.18. The median age in the county was 46.1 years with 19.3% of the population under 18. The median income for a household was $52,371 and the poverty rate was 14.5%.[30]

2010 census

editAs of the 2010 United States census, there were 33,107 people, 13,869 households, and 9,359 families residing in the county.[31] The population density was 108.4 inhabitants per square mile (41.9/km2). There were 15,918 housing units at an average density of 52.1 units per square mile (20.1 units/km2).[32] The racial makeup of the county was 98.0% white, 0.5% black or African American, 0.4% Asian, 0.1% American Indian, 0.1% from other races, and 0.9% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 0.8% of the population.[31] In terms of ancestry, 26.2% were German, 17.6% were Irish, 13.0% were English, 9.6% were American, 7.0% were Polish, and 6.6% were Italian.[33]

Of the 13,869 households, 28.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.4% were married couples living together, 11.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 32.5% were non-families, and 28.0% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.85. The median age was 44.3 years.[31]

The median income for a household in the county was $34,419 and the median income for a family was $43,482. Males had a median income of $41,193 versus $26,585 for females. The per capita income for the county was $21,064. About 13.9% of families and 18.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.5% of those under age 18 and 9.8% of those age 65 or over.[34]

2000 census

editAt the census of 2000, there were 35,519 people, 14,207 households, and 10,101 families residing in the county. The population density was 116 inhabitants per square mile (45/km2). There were 15,814 housing units at an average density of 52 units per square mile (20 units/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 98.40% White, 0.43% Black or African American, 0.11% Native American, 0.25% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.12% from other races, and 0.67% from two or more races. 0.64% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 14,207 households, out of which 29.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.80% were married couples living together, 10.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.90% were non-families. 25.60% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 2.91.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 22.80% under the age of 18, 7.30% from 18 to 24, 27.10% from 25 to 44, 26.40% from 45 to 64, and 16.30% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 94.80 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.60 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $30,989, and the median income for a family was $39,053. Males had a median income of $31,821 versus $19,053 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,472. About 12.40% of families and 16.60% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.30% of those under age 18 and 11.30% of those age 65 or over. 0% of those under age 18 and 11.30% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

editMarshall County was usually Democratic between the New Deal and Bill Clinton, after having previously been a Unionist and Republican county since the Civil War. Since 2000 it has been won by Republican candidates.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 10,435 | 74.11% | 3,455 | 24.54% | 190 | 1.35% |

| 2016 | 9,666 | 72.39% | 2,918 | 21.85% | 769 | 5.76% |

| 2012 | 8,135 | 62.77% | 4,484 | 34.60% | 341 | 2.63% |

| 2008 | 7,759 | 55.42% | 5,996 | 42.83% | 246 | 1.76% |

| 2004 | 8,516 | 56.50% | 6,435 | 42.70% | 121 | 0.80% |

| 2000 | 6,859 | 50.81% | 6,000 | 44.45% | 639 | 4.73% |

| 1996 | 4,460 | 32.35% | 7,045 | 51.11% | 2,280 | 16.54% |

| 1992 | 4,463 | 29.33% | 7,298 | 47.95% | 3,458 | 22.72% |

| 1988 | 6,793 | 45.96% | 7,903 | 53.47% | 83 | 0.56% |

| 1984 | 8,615 | 51.85% | 7,947 | 47.83% | 54 | 0.32% |

| 1980 | 7,252 | 45.56% | 7,832 | 49.21% | 832 | 5.23% |

| 1976 | 6,705 | 43.69% | 8,641 | 56.31% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1972 | 10,966 | 63.23% | 6,378 | 36.77% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1968 | 7,252 | 42.46% | 8,449 | 49.47% | 1,379 | 8.07% |

| 1964 | 6,175 | 34.44% | 11,757 | 65.56% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 9,147 | 49.86% | 9,197 | 50.14% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 10,223 | 57.80% | 7,463 | 42.20% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 9,271 | 51.62% | 8,689 | 48.38% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 6,986 | 46.20% | 7,989 | 52.83% | 147 | 0.97% |

| 1944 | 7,800 | 52.09% | 7,174 | 47.91% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 9,324 | 51.16% | 8,900 | 48.84% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 7,967 | 46.21% | 9,198 | 53.35% | 76 | 0.44% |

| 1932 | 7,416 | 47.40% | 7,994 | 51.09% | 237 | 1.51% |

| 1928 | 9,204 | 65.22% | 4,785 | 33.91% | 123 | 0.87% |

| 1924 | 7,413 | 55.56% | 4,710 | 35.30% | 1,219 | 9.14% |

| 1920 | 7,208 | 58.22% | 4,814 | 38.89% | 358 | 2.89% |

| 1916 | 3,699 | 53.42% | 2,997 | 43.28% | 229 | 3.31% |

| 1912 | 1,610 | 25.24% | 2,405 | 37.71% | 2,363 | 37.05% |

Cities

edit- Benwood

- Cameron

- Glen Dale

- McMechen

- Moundsville (county seat)

- Wheeling (mostly in Ohio County)

Unincorporated Communities

edit- Adaline

- Bannen

- Balls-Andersonville

- Beeler’s Station

- Belton (Denver)

- Big Run

- Board Tree (Georgetown)

- Calis (Seatonville)

- Captina

- Chestnut Hill/Archville/Thompson/Round Bottom

- Clouston

- Cresap (Woco)

- Dallas/West Union

- Ella

- Fairview

- Franklin

- Glen Dale/McMechen Heights

- Glen Easton

- Golden

- Graysville (Hornsbrook)

- Howard

- Kausooth

- Knoxville (Goosetown)

- Limestone (Maysville)

- Loudenville

- Lynn Camp

- Majorsville

- McKeefry/Washington Lands

- Meighen

- Millsboro

- Mount Olivet

- Mozart

- Natrium

- Sherrard

- Pleasant Valley

- Poplar Springs

- Proctor

- Rock Lick

- Rosbys Rock

- Saint Joseph (German Settlement)

- Sand Hill

- Teutonia

- Viola

- Welcome

- Wolf Run

- Wood Hill

- Woodlands

- Woodruff

Magisterial Districts

editCurrent

edit- District 1

- District 2

- District 3

Historic

edit- Cameron

- Clay

- Franklin

- Liberty

- Meade

- Sand Hill

- Union

- Washington

- Webster

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "WVDCH-Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex". www.wvculture.org. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 23, 2001. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Marshall County Historical Society. History of Marshall County, West Virginia. Marceline, Mo., Walsworth, 1984.975.416 M367m.

- ^ Marshall County Historical Society, History of Marshall County, West Virginia 1984 (third printing 1989) pp. 6, 8.

- ^ a b Marshall County 1984 History, p. 10.

- ^ Scott Powell, History of Marshall County, West Virginia (1925; reprinted by Heritage Books Inc. 1998) pp. 14–17 ISBN 0-7884-0920-4

- ^ a b History. County Marshall wvculture.org

- ^ "Lawrenceville, West Virginia | Discovering Lewis & Clark ®". April 2, 2021.

- ^ Marshall County 1984 History, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 200.

- ^ Marshall County 1925 History, pp. 105–107.

- ^ a b Marshall County 1984 History, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Marshall County history sources". Archived from the original on April 13, 2016.

- ^ "E-WV | Rosbys Rock".

- ^ NRIS for Bushrod Washington Price House at Section 8 p. 3 available at http://www.wvculture.org/shpo/nr/pdf/marshall/95001326.pdf

- ^ "Biographical Sketches: James Burley". Archived from the original on September 8, 2015.

- ^ Leckey, Howard L.; Leckey (June 2009). The Tenmile Country and Its Pioneer Families. Genealogical Publishing Com. ISBN 9780806350974.

- ^ "Civil War Notebook: Remembrance M. Swan". August 25, 2010.

- ^ Otis K. Rice & Stephen W. Brown, West Virginia: A History, 2nd ed., University Press of Kentucky, Lexington (1993), p. 240.

- ^ a b United States Census Bureau, U.S. Decennial Census, Tables of Minor Civil Divisions in West Virginia, 1870–2010.

- ^ a b "E-WV | Marshall County".

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021". Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 27, 2018.