Martin(us) van Marum (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈmɑrtɪɱ vɑ ˈmaːrʏm]; 20 March 1750 – 26 December 1837) was a Dutch physician, inventor, scientist and teacher, who studied medicine and philosophy in Groningen. Van Marum introduced modern chemistry in the Netherlands after the theories of Antoine Lavoisier, and several scientific applications for general use. He became famous for his demonstrations with instruments, most notable the large electricity machine, to show statical electricity and chemical experiments while curator for the Teylers Museum.

Martin van Marum | |

|---|---|

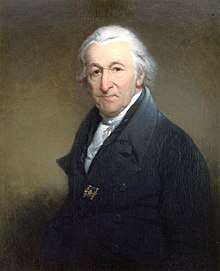

Van Marum portrait by Charles Howard Hodges. | |

| Born | March 20, 1750 |

| Died | December 26, 1837 (aged 87) |

| Known for | Large electricity machine |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | Teylers Museum |

He researched on the validity of Boyle's law on gases other than air. He found that ammonium gas deviated from Boyle's law with increasing pressure, and it liquified at 7 atm. With this, he was the first to liquify ammonium.[1]

Biography

editEarly career

editBorn in Delft, Van Marum moved to Haarlem in 1776 "because the Haarlemmers had more taste in the sciences than anywhere else in the Netherlands"[by whom?].[2] After his arrival in Haarlem he began to practise medicine, but devoted himself mainly to lecturing on physical subjects and creating instruments to demonstrate physical theory. He must have made a big impression on Haarlem society, because he became a member of the Dutch Society of Science in the same year, but was named director and curator of their cabinet of curiosities in the next year.[3]

Van Marum received at first no salary, but by scaring off the former cabinet concierge Nicolaus Linder, he was able to collect Linder's' annual salary of 100 guilders, and when the cabinet moved later in 1777 to new quarters in the Grote Houtstraat 51, Van Marum lived there as concierge.[3] He managed to scare off Linder by obtaining permission from the society to allow his servants to keep tips they received from cabinet visitors; a source of income that Linder had come to rely on. Then Van Marum increased this salary to 300 from 100 by adding responsibilities to his list of duties, such as a summer garden in the Rozenprieel and eliminating other expenses.[3]

Curator of two museums

editIn 1779, he was entrusted with the care of the Second society left to Haarlem by Pieter Teyler van der Hulst (1702–1778), which led under his direction to the foundation of the Teylers Museum. The Teyler legacy was split into three societies, one for religion, one for science, and one for the arts, known as the first, second, and third societies. The caretakers had to meet in Teyler's home weekly, and each society had 5 caretakers, so all of the gentlemen involved lived in Haarlem.

In 1794, Van Marum became secretary as well as director of the Dutch Society of Science. Under his management, both societies were advanced to the position of the most noted in Europe. Period travelogues mention both Museums.[4]

Besides being involved with the Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen, he was an ordinary member (5 December 1776) and a corresponding member (from 25 December 1776) of the Provinciaal Utrechtsch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, a member of the Bataafsch Genootschap der Proefondervindelijke wijsbegeerte from 1784, a member of the Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen from 27 August 1782, corresponding member of the Académie des Sciences from 1783, and a member of the Vergadering van Notabelen voor het departement Zuiderzee from 29 March 1814. In 1808 he was asked by Louis Bonaparte to be a member of the committee for the formation of the Koninklijk Instituut along with Jeronimo de Bosch, Jean Henri van Swinden, and Martinus Stuart. He became member of the institute the same year.[5]

Merging societies, separate collections

editUnder his guidance the two societies slowly merged. His name is associated with the Electriseermachine, the largest electricity demonstration machine with Leiden jars built in the 18th century and at the time a crowd pleaser for the young Teylers museum. The demonstration model is still on display, as is a smaller version in the Museum Boerhaave of Leiden. Van Marum's researches (especially in connection with electricity) were remarkable for their number and variety.

The Teyler's Museum kept its role as a museum of scientific research (some of the periodical subscriptions he started are still running) and is a repository of important scientific demonstration models from the period. Not only items regarding electricity, but also weather stations, industrial models, steam engines, and other examples of the budding industrial revolution were collected and lovingly displayed. The collection of the Teyler's was mostly based on scientific theory, while the collection of the Dutch Society of Science was mostly based on scientific practise. The rooms in the Grote Houtstraat were filled with stuffed animals and other "naturalia", while the summer garden was a modern continuation of Linder's old Linnaeus hortus once located behind the original city hall quarters in the Prinsenhof. Since Linder had not known any Latin, it was easier for Van Marum to entertain foreign visitors with stories of Linnaean trivia and of course, the Haarlem story of tulip mania.

Teylers Museum

editIn 1784, when the Teylers Museum opened its new 'Oval Room', the artist Vincent Jansz van der Vinne was hired as curator of the art collection and lived in Pieter Teyler's former residence that was called the "Fundatiehuis" as concierge and caretaker of the art collection.[6] He left the next year because of continuous disagreements with Van Marum over art and the opening hours of the museum.[6]

Van der Vinne was an artist born into an important Haarlem artist family – he was the great-grandson of Vincent van der Vinne. The Teyler's museum replaced him with another local artist, Wybrand Hendricks, who painted the famous oval room and many other Haarlem scenes. Hendricks is largely responsible for the Teyler's collection of Old Master prints, most notably the purchase in Rome 1790 of a print & drawing collection formerly owned by Christina of Sweden.[6] Apparently he got along under Van Marum, but when he left in 1819 at the age of 75, the Teyler's decided to discontinue the purchase of art "for the decline in art enthusiasts in this city".[6]

During the tenure of Hendriks, Van Marum himself was busy giving public demonstrations of electricity in the Oval room, but was also collecting in this period (this is why he was so involved with the lifestyle of the concierge of the Fundatiehuis, since he was there every day).[6] He concentrated on scientific publications for the Teyler library. He concentrated his efforts on three aspects: 1) Greek and Latin authors, among them the church fathers, 2) Works of natural history including travelogues, and 3) natural history periodicals, including all publications of the Royal Society of London and all publications of the Dutch Society of Science, which Teyler had been a member of, but could not be on the board of, due to religious differences with the board. The criteria for purchase was always expense. If a Society member could afford to purchase it himself it was not worth adding to the collection. Any member could suggest purchases, however, which explains why the collection is filled with richly illustrated examples of contemporary publications. The most impressive of these are the large illustrated books of travellers. To view the collection, Van Marum organised gentleman evenings in Pieter Teyler's library, a tradition that still exists.

Legacy

editThough the public is allowed access during the day to the museum rooms, the private rooms of Pieter Teyler in the "Fundatiehuis" are only open one day a year, on Monument Day. Because of its rich scientific tradition, many noted scholars of Physics moved to Haarlem to work at Teyler's, including Nobel Prize in Physics winners Pieter Zeeman and Hendrik Lorentz.

Of Van Marum's three categories, only the first was discontinued at the close of the 19th century. The collection of periodicals which has been expanded through exchange networks, contains uninterrupted series that are among the oldest in the world.

The Teyler's museum created a new wing in 1996 to house a rotational display of Van Marum's library collection, such as the works of John James Audubon in combination with contemporary stuffed birds of Naturalis.

References

edit- ^ Ford, P. J. "Towards the absolute zero: The early history of low temperatures." South African Journal of Science 77.6 (1981): 244-248.

- ^ Deugd boven geweld – Een geschiedenis van Haarlem 1245–1995. Historisch Werkgroep Haarlem en Gemeentearchief, 1995.

- ^ a b c Johannes Abraham Bierens de Haan, De geschiedenis van een verdwenen Haarlemsch museum van natuurlijke historie. Het Kabinet van Naturalien van de Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen 1759–1866. Haarlem, F. Bohn, 1941.

- ^ p 188 van Marum's museum in Journal of a horticultural tour through some parts of Flanders, Holland, and the North of France, in the autumn of 1817 by Patrick Neill, on the Google Books Library Project

- ^ "Martinus van Marum (1750–1837)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Van kastelein tot directeur. Teylers museum in de 20ste eeuw. Stichting Vrienden van Teylers Museum (1975–2000), ISBN 90-71835-13-8

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Marum, Martin van". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

edit- Noord-Hollandsarchief Archives of North Holland

- Teylers Museum

- Dutch Society of Science (in Dutch)