The Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus), also known as the Alameda striped racer, is a federally threatened subspecies of California whipsnake (M. lateralis). It is a colubrid snake distinguishable by its broad head, large eyes, black and orange coloring with a yellow stripe down each side, and slender neck. The California whipsnake is found in California's northern and coastal chaparral. The Alameda whipsnake is a wary creature known for its speed and climbing abilities utilized when escaping predators or hunting prey. In winter months, the Alameda whipsnake hibernates in rock crevices and rodent burrows.

| Alameda whipsnake | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Masticophis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | M. l. euryxanthus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus (Riemer, 1954)

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

Since 1992, the Alameda whipsnakes have been eliminated from 35 of 60 historical localities. The snake was first collected by Archie Mossman and later described by Riemer[5] in 1954. Unlike the parent species, the California whipsnake, the Alameda whipsnake has been reduced to just five areas with little or no interchange due to habitat loss, alteration, and fragmentation. The biggest threat to the Alameda Whipsnake is human development in the snake's habitat. Urban sprawl is increasing at a rapid rate, and introducing the snake to direct alteration like construction of development, and indirect like pets and public recreation.

The California Environmental Quality Act and California Endangered Species Act afforded the Alameda whipsnake some conservation benefits prior to the federal listing, but these laws by themselves were far from adequate to protect the species. The listing of the Alameda whipsnake as federally threatened increases the ability of public land agencies to promote conservation and management plans that take into consideration the specialized environmental and biological needs of this snake.

Behavior

editDiet

editThe Alameda whipsnake is a diurnal ectotherm that is often seen foraging in the daytime. As it searches for food, the head and the front half of the body are held off of the ground for the most optimal vision to find prey. The snake has two seasonal peaks in activity, one during the spring mating season and the other during late summer or early fall. In the spring, males tend to forage and search for mates while females stay in hibernation. Female peak activity only tends to be a few days in the spring when they are looking for egg laying sites. When the Alameda striped racer finds prey, such as the Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis) or the Western skink (Eumeces skiltonianus), it takes the prey quickly, holds it tight under the loops of its body, and swallows it whole without constriction. Alameda whipsnakes are great climbers and are able to quickly move through trees and shrubs to hunt prey or escape predators (US Fish and Wildlife 2006).[6][7]

Reproduction

editCourtship and mating are observed from late March through mid-June. During this time, males move around throughout their home ranges, but females appear to remain at or near their hibernacula, where mating occurs. Female egg laying sites are typically located in grasslands with scattered shrub habitat. Copulation commences soon after emergence from winter hibernacula (Swaim 1994). Females begin laying eggs in mid-late May. Average clutch size is just greater than 7 eggs with a significant correlation between body size and clutch size (Goldberg 1975). Once the female lays her eggs, it will be about 3 months of incubation before the young appear in the late summer and into the fall (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2002).[8][9][10][11]

Life history

editThe Alameda whipsnake is an ectotherm. It might first emerge by sliding its head out of its burrow into the sun. Then it will bask its whole body until its temperature is 91.4–93.4 °F (33.0–34.1 °C). It has two annual peaks in activity. The first extends from March, when it leaves its hibernaculum, until mid-June, following courtship and mating. Hatchlings have been located during the second smaller peak in activity, from August through November. Afterwards, like mature snakes, they will seek out a hibernaculum for winter hibernation. Alameda whipsnakes require 2–3 years to reach maturity, may live for eight years, and can reach a length of five feet. The Alameda whipsnake's home range may have one or more core areas and specific retreats. They are good climbers, and are able to escape into scrub or trees (US Fish and Wildlife 2006).[6][7][10]

Description and physiology

editAdults reach a length of 3 to 4 feet (0.91 to 1.22 m). Their back is colored sooty black or dark brown with a distinct yellow-orange stripe down each side. The front part of the Alameda whipsnake's underside is orange-rufous colored; however, the midsection is cream colored, and the rear section and tail are pinkish. The Alameda whipsnake is a slender, fast-moving, diurnal snake with a broad head, large eyes, and slender neck.

Habitat and distribution

editHistorical range

editThe whipsnake once had a continuous range in the inner Coast Ranges in western and central Contra Costa and Alameda counties (California) which is now fragmented into five populations (US Fish and Wildlife Service 1997).[12]

Present population size and range

editThe Alameda whipsnake population has been fragmented into five mostly isolated subpopulations whose numbers are unknown, but which are certain to be rapidly declining as suitable habitat is lost to urban development. Little population abundance data exists for the Alameda whipsnake. Almost all trapping studies targeting this subspecies have been designed to determine presence or absence for regulatory purposes and assessing impacts to potential habitat. As such, monitoring is most often habitat based; assuming snake abundance is positively correlated with the amount of coastal scrub or chaparral vegetation and rock lands present.

The Alameda whipsnake is non-migratory, so distribution is not large. The current distribution has been fragmented into five populations; the Tilden-Briones, Oakland-Las Trampas, and Mount Diablo-Black Hills populations in Contra Costa County, the Hayward-Pleasanton Ridge population in Alameda County, and the Sunol-Cedar Mountain population largely in Alameda County with extensions into San Joaquin and Santa Clara Counties, with little to no interaction between the populations. It is estimated that the snakes go no more than 1 mile away from core coastal shrub habitat.

This subspecies inhabits a variety of different chaparral, which includes vegetation composed of broad-leaved evergreen shrubs, bushes, and small trees usually less than 2.5 m. The cover is typically dense and dry during the striped racer's peak activity. Although this is where they reside, they forage in other communities in the inner Coast Range, like grasslands, pond and stream edges, and woodlands. Rock outcrops are favorable whipsnake habitats as well, as they provide dens, refuge for predators, and cool areas to escape from excessive heat. Whipsnake prey is also abundant in rocky outcrops, giving the snake plenty of foraging opportunity. The habitat must be a good mix of sunny and shady sites, partially open shrubland, and foraging sites for the whipsnake to meet its biological needs.

Human impact and major threats

editThe most significant threat to the Alameda whipsnake is human impact. Approximately, 60 percent of the snake's habitat is owned by the public. One of the major threats to the Alameda whipsnake is habitat loss as a result of urban expansion. Road and highway construction has been increasing, making the snake even more vulnerable of extinction. Even if urban development is not directly ruining the habitat, adjacent development can have a major impact as well. Being near humans can increase the likelihood of being hunted by feral pets, or killed by the public in recreation activities. Another human impact is fire suppression efforts, as it can alter habitat in two significant ways. It increases the chances of catastrophic fires in overgrown habitat, and would result in a buildup of flammable fuel in the shrubland. Also, fire suppression can reduce biodiversity of the habitat the snake requires.[citation needed] Pest control efforts near protected habitat also introduces rodenticides, burrow fumigants, herbicides, and pesticides that may harm the Alameda Whipsnake directly.

Aside from human impact, the Alameda whipsnake must avoid its predators. The Alameda whipsnake's predators are California kingsnakes, raccoons, striped skunks, opossums, coyotes, gray foxes, red foxes, hawks, feral pigs, dogs, and cats.[10]

Current conservation efforts

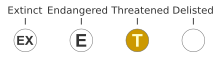

editESA listing history

editThe Alameda whipsnake was first listed as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act in 1971 and the US Endangered Species Act listed it in 1997. The first 5-year review was established in 2011 and recommended no change from current listing. The California Environmental Quality Act and California Endangered Species Act afforded the Alameda whipsnake some conservation benefits prior to its being federally listed, but these laws by themselves were far from adequate to protect the snake. The listing of the Alameda whipsnake as federally threatened will increase the ability of public land agencies to promote conservation and management plans that take into consideration the specialized environmental and biological needs of this snake. These plans include an increased ability to conduct prescribed burns throughout the whipsnake's range; control native, introduced, and feral predators; regulate recreational use, and develop educational programs for the benefit of the Alameda whipsnake. With appropriate management, areas of open space managed by the East Bay Regional Park District, East Bay Municipal Utilities District, and Mount Diablo State Park may be better utilized to protect the Alameda Whipsnake.[6][12]

References

edit- ^ NatureServe (7 April 2023). "Coluber lateralis euryxanthus". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "Alameda whipsnake (=striped racer) (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ 62 FR 64306

- ^ "Masticophis lateralis subsp. euryxanthus (Riemer, 1954)". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Riemer, William J. (1954-02-19). "A New Subspecies of the Snake Masticophis lateralis from California". Copeia. 1954 (1): 45–48. doi:10.2307/1440636. ISSN 0045-8511. JSTOR 1440636.

- ^ a b c Alvarez, Jeff A.; Davidson, Kelly A.; Villalba, Fernando; Amador, Denise; Sprague, Angelica V. (2021). "Notes: Atypical Habitat Use by the Threatened Alameda Whipsnake in the Eastern Bay Area of California" (PDF). Western Wildlife. 8 (1): 8–12. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b Alvarez, Jeff A.; Murphy, Amanda C. (2022). "Arboreality in the California Whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis): Implications for Survey Techniques". Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences. 121 (1): 34–40. doi:10.3160/0038-3872-121.1.34.

- ^ Goldberg, Stephen R. (1975-10-27). "Reproduction in the Striped Racer, Masticophis lateralis (Colubridae)". Journal of Herpetology. 9 (4): 361–363. doi:10.2307/1562941. ISSN 0022-1511. JSTOR 1562941.

- ^ Hammerson, Geoffrey A. (1978-04-24). "Observations on the Reproduction, Courtship, and Aggressive Behavior of the Striped Racer, Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus (Reptilia, Serpentes, Colubridae)". Journal of Herpetology. 12 (2): 253–255. doi:10.2307/1563418. ISSN 0022-1511. JSTOR 1563418.

- ^ a b c Swaim, Karen E. (1998-12-14). Results of a live trapping survey for the Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) at the Site 300 facilities of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (Report). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. doi:10.2172/8320. Retrieved 26 April 2023 – via UNT Digital Library.

- ^ "Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles". Evolution. 19 (2): 268. June 1965. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1965.tb01719.x. ISSN 0014-3820. S2CID 221728532.

- ^ a b Schafer, D.W.; Robeck, K.E. (1980-06-01). Threatened and endangered fish and wildlife of the Midwest (Technical Report). Argonne National Lab. doi:10.2172/5073320. OSTI 5073320. ANL/EES-TM-101.

External links

edit- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS): Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus species Account — (Alameda Whipsnake).

- CaliforniaHerps.com: Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus — Alameda Striped Racer (Alameda whipsnake)

- [1]

- [2]

- Alameda Whipsnake - Amphibians and Reptiles, Endangered Species Accounts | Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office

- Alameda whipsnake

- Alameda Striped Racer - Coluber lateralis euryxanthus