In mathematics, a knot is an embedding of the circle (S1) into three-dimensional Euclidean space, R3 (also known as E3). Often two knots are considered equivalent if they are ambient isotopic, that is, if there exists a continuous deformation of R3 which takes one knot to the other.

A crucial difference between the standard mathematical and conventional notions of a knot is that mathematical knots are closed — there are no ends to tie or untie on a mathematical knot. Physical properties such as friction and thickness also do not apply, although there are mathematical definitions of a knot that take such properties into account. The term knot is also applied to embeddings of S j in Sn, especially in the case j = n − 2. The branch of mathematics that studies knots is known as knot theory and has many relations to graph theory.

Formal definition

editA knot is an embedding of the circle (S1) into three-dimensional Euclidean space (R3),[1] or the 3-sphere (S3), since the 3-sphere is compact.[2] [Note 1] Two knots are defined to be equivalent if there is an ambient isotopy between them.[3]

Projection

editA knot in R3 (or alternatively in the 3-sphere, S3), can be projected onto a plane R2 (respectively a sphere S2). This projection is almost always regular, meaning that it is injective everywhere, except at a finite number of crossing points, which are the projections of only two points of the knot, and these points are not collinear. In this case, by choosing a projection side, one can completely encode the isotopy class of the knot by its regular projection by recording a simple over/under information at these crossings. In graph theory terms, a regular projection of a knot, or knot diagram is thus a quadrivalent planar graph with over/under-decorated vertices. The local modifications of this graph which allow to go from one diagram to any other diagram of the same knot (up to ambient isotopy of the plane) are called Reidemeister moves.

-

Reidemeister move 1

-

Reidemeister move 2

-

Reidemeister move 3

Types of knots

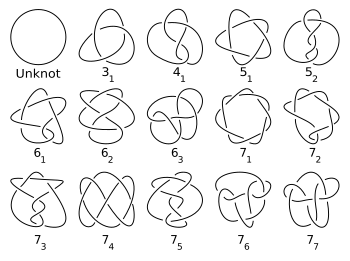

editThe simplest knot, called the unknot or trivial knot, is a round circle embedded in R3.[4] In the ordinary sense of the word, the unknot is not "knotted" at all. The simplest nontrivial knots are the trefoil knot (31 in the table), the figure-eight knot (41) and the cinquefoil knot (51).[5]

Several knots, linked or tangled together, are called links. Knots are links with a single component.

Tame vs. wild knots

editA polygonal knot is a knot whose image in R3 is the union of a finite set of line segments.[6] A tame knot is any knot equivalent to a polygonal knot.[6][Note 2] Knots which are not tame are called wild,[7] and can have pathological behavior.[7] In knot theory and 3-manifold theory, often the adjective "tame" is omitted. Smooth knots, for example, are always tame.

Framed knot

editA framed knot is the extension of a tame knot to an embedding of the solid torus D2 × S1 in S3.

The framing of the knot is the linking number of the image of the ribbon I × S1 with the knot. A framed knot can be seen as the embedded ribbon and the framing is the (signed) number of twists.[8] This definition generalizes to an analogous one for framed links. Framed links are said to be equivalent if their extensions to solid tori are ambient isotopic.

Framed link diagrams are link diagrams with each component marked, to indicate framing, by an integer representing a slope with respect to the meridian and preferred longitude. A standard way to view a link diagram without markings as representing a framed link is to use the blackboard framing. This framing is obtained by converting each component to a ribbon lying flat on the plane. A type I Reidemeister move clearly changes the blackboard framing (it changes the number of twists in a ribbon), but the other two moves do not. Replacing the type I move by a modified type I move gives a result for link diagrams with blackboard framing similar to the Reidemeister theorem: Link diagrams, with blackboard framing, represent equivalent framed links if and only if they are connected by a sequence of (modified) type I, II, and III moves. Given a knot, one can define infinitely many framings on it. Suppose that we are given a knot with a fixed framing. One may obtain a new framing from the existing one by cutting a ribbon and twisting it an integer multiple of 2π around the knot and then glue back again in the place we did the cut. In this way one obtains a new framing from an old one, up to the equivalence relation for framed knots„ leaving the knot fixed. [9] The framing in this sense is associated to the number of twists the vector field performs around the knot. Knowing how many times the vector field is twisted around the knot allows one to determine the vector field up to diffeomorphism, and the equivalence class of the framing is determined completely by this integer called the framing integer.

Knot complement

editGiven a knot in the 3-sphere, the knot complement is all the points of the 3-sphere not contained in the knot. A major theorem of Gordon and Luecke states that at most two knots have homeomorphic complements (the original knot and its mirror reflection). This in effect turns the study of knots into the study of their complements, and in turn into 3-manifold theory.[10]

JSJ decomposition

editThe JSJ decomposition and Thurston's hyperbolization theorem reduces the study of knots in the 3-sphere to the study of various geometric manifolds via splicing or satellite operations. In the pictured knot, the JSJ-decomposition splits the complement into the union of three manifolds: two trefoil complements and the complement of the Borromean rings. The trefoil complement has the geometry of H2 × R, while the Borromean rings complement has the geometry of H3.

Harmonic knots

editParametric representations of knots are called harmonic knots. Aaron Trautwein compiled parametric representations for all knots up to and including those with a crossing number of 8 in his PhD thesis.[11][12]

Applications to graph theory

editMedial graph

editAnother convenient representation of knot diagrams [13][14] was introduced by Peter Tait in 1877.[15][16]

Any knot diagram defines a plane graph whose vertices are the crossings and whose edges are paths in between successive crossings. Exactly one face of this planar graph is unbounded; each of the others is homeomorphic to a 2-dimensional disk. Color these faces black or white so that the unbounded face is black and any two faces that share a boundary edge have opposite colors. The Jordan curve theorem implies that there is exactly one such coloring.

We construct a new plane graph whose vertices are the white faces and whose edges correspond to crossings. We can label each edge in this graph as a left edge or a right edge, depending on which thread appears to go over the other as we view the corresponding crossing from one of the endpoints of the edge. Left and right edges are typically indicated by labeling left edges + and right edges –, or by drawing left edges with solid lines and right edges with dashed lines.

The original knot diagram is the medial graph of this new plane graph, with the type of each crossing determined by the sign of the corresponding edge. Changing the sign of every edge corresponds to reflecting the knot in a mirror.

Linkless and knotless embedding

editIn two dimensions, only the planar graphs may be embedded into the Euclidean plane without crossings, but in three dimensions, any undirected graph may be embedded into space without crossings. However, a spatial analogue of the planar graphs is provided by the graphs with linkless embeddings and knotless embeddings. A linkless embedding is an embedding of the graph with the property that any two cycles are unlinked; a knotless embedding is an embedding of the graph with the property that any single cycle is unknotted. The graphs that have linkless embeddings have a forbidden graph characterization involving the Petersen family, a set of seven graphs that are intrinsically linked: no matter how they are embedded, some two cycles will be linked with each other.[17] A full characterization of the graphs with knotless embeddings is not known, but the complete graph K7 is one of the minimal forbidden graphs for knotless embedding: no matter how K7 is embedded, it will contain a cycle that forms a trefoil knot.[18]

Generalization

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) |

In contemporary mathematics the term knot is sometimes used to describe a more general phenomenon related to embeddings. Given a manifold M with a submanifold N, one sometimes says N can be knotted in M if there exists an embedding of N in M which is not isotopic to N. Traditional knots form the case where N = S1 and M = R3 or M = S3.[19][20]

The Schoenflies theorem states that the circle does not knot in the 2-sphere: every topological circle in the 2-sphere is isotopic to a geometric circle.[21] Alexander's theorem states that the 2-sphere does not smoothly (or PL or tame topologically) knot in the 3-sphere.[22] In the tame topological category, it's known that the n-sphere does not knot in the n + 1-sphere for all n. This is a theorem of Morton Brown, Barry Mazur, and Marston Morse.[23] The Alexander horned sphere is an example of a knotted 2-sphere in the 3-sphere which is not tame.[24] In the smooth category, the n-sphere is known not to knot in the n + 1-sphere provided n ≠ 3. The case n = 3 is a long-outstanding problem closely related to the question: does the 4-ball admit an exotic smooth structure?

André Haefliger proved that there are no smooth j-dimensional knots in Sn provided 2n − 3j − 3 > 0, and gave further examples of knotted spheres for all n > j ≥ 1 such that 2n − 3j − 3 = 0. n − j is called the codimension of the knot. An interesting aspect of Haefliger's work is that the isotopy classes of embeddings of S j in Sn form a group, with group operation given by the connect sum, provided the co-dimension is greater than two. Haefliger based his work on Stephen Smale's h-cobordism theorem. One of Smale's theorems is that when one deals with knots in co-dimension greater than two, even inequivalent knots have diffeomorphic complements. This gives the subject a different flavour than co-dimension 2 knot theory. If one allows topological or PL-isotopies, Christopher Zeeman proved that spheres do not knot when the co-dimension is greater than 2. See a generalization to manifolds.

See also

edit- Knot theory – Study of mathematical knots

- Knot invariant – Function of a knot that takes the same value for equivalent knots

- List of mathematical knots and links

Notes

edit- ^ Note that the 3-sphere is equivalent to R3 with a single point added at infinity (see one-point compactification).

- ^ A knot is tame if and only if it can be represented as a finite closed polygonal chain

References

edit- ^ Armstrong (1983), p. 213.

- ^ Cromwell 2004, p. 33; Adams 1994, pp. 246–250

- ^ Cromwell (2004), p. 5.

- ^ Adams (1994), p. 2.

- ^ Adams 1994, Table 1.1, p. 280; Livingstone 1993, Appendix A: Knot Table, p. 221

- ^ a b Armstrong 1983, p. 215

- ^ a b Charles Livingston (1993). Knot Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-88385-027-5.

- ^ Kauffman, Louis H. (1990). "An invariant of regular isotopy" (PDF). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 318 (2): 417–471. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1990-0958895-7.

- ^ Elhamdadi, Mohamed; Hajij, Mustafa; Istvan, Kyle (2019), Framed Knots, arXiv:1910.10257.

- ^ Adams 1994, pp. 261–2

- ^ Trautwein, Aaron K. (1995). Harmonic knots (PhD). Dissertation Abstracts International. Vol. 56–06. University of Iowa. p. 3234. OCLC 1194821918. ProQuest 304216894.

- ^ Trautwein, Aaron K. (1998). "18. An introduction to Harmonic Knots". In Stasiak, Andrzej; Katritch, Vsevolod; Kauffman, Louis H. (eds.). Ideal Knots. World Scientific. pp. 353–363. ISBN 978-981-02-3530-7.

- ^ Adams, Colin C. (2004). "§2.4 Knots and Planar Graphs". The Knot Book: An Elementary Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Knots. American Mathematical Society. pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-0-8218-3678-1.

- ^ Entrelacs.net tutorial

- ^ Tait, Peter G. (1876–1877). "On Knots I". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 28: 145–190. doi:10.1017/S0080456800090633.

Revised May 11, 1877.

- ^ Tait, Peter G. (1876–1877). "On Links (Abstract)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 9 (98): 321–332. doi:10.1017/S0370164600032363.

- ^ Robertson, Neil; Seymour, Paul; Thomas, Robin (1993), "A survey of linkless embeddings", in Robertson, Neil; Seymour, Paul (eds.), Graph Structure Theory: Proc. AMS–IMS–SIAM Joint Summer Research Conference on Graph Minors (PDF), Contemporary Mathematics, vol. 147, American Mathematical Society, pp. 125–136.

- ^ Ramirez Alfonsin, J. L. (1999), "Spatial graphs and oriented matroids: the trefoil", Discrete and Computational Geometry, 22 (1): 149–158, doi:10.1007/PL00009446.

- ^ Carter, J. Scott; Saito, Masahico (1998). Knotted Surfaces and their Diagrams. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs. Vol. 55. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-0593-2. MR 1487374.

- ^ Kamada, Seiichi (2017). Surface-Knots in 4-Space. Springer Monographs in Mathematics. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-4091-7. ISBN 978-981-10-4090-0. MR 3588325.

- ^ Hocking, John G.; Young, Gail S. (1988). Topology (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. p. 175. ISBN 0-486-65676-4. MR 1016814.

- ^ Calegari, Danny (2007). Foliations and the geometry of 3-manifolds. Oxford Mathematical Monographs. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-19-857008-0. MR 2327361.

- ^ Mazur, Barry (1959). "On embeddings of spheres". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 65 (2): 59–65. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1959-10274-3. MR 0117693. Brown, Morton (1960). "A proof of the generalized Schoenflies theorem". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 66 (2): 74–76. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1960-10400-4. MR 0117695. Morse, Marston (1960). "A reduction of the Schoenflies extension problem". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 66 (2): 113–115. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1960-10420-X. MR 0117694.

- ^ Alexander, J. W. (1924). "An Example of a Simply Connected Surface Bounding a Region which is not Simply Connected". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 10 (1). National Academy of Sciences: 8–10. Bibcode:1924PNAS...10....8A. doi:10.1073/pnas.10.1.8. ISSN 0027-8424. JSTOR 84202. PMC 1085500. PMID 16576780.

Bibliography

edit- Adams, Colin C. (1994). The Knot Book: An Elementary Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Knots. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-2393-6.

- Armstrong, M. A. (1983) [1979]. Basic Topology. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 0-387-90839-0.

- Cromwell, Peter R. (2004). Knots and Links. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809767. ISBN 0-521-83947-5. MR 2107964.

- Farmer, David W.; Stanford, Theodore B. (1995). Knots and Surfaces: A Guide to Discovering Mathematics. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-7265-9.

- Livingstone, Charles (1993). Knot Theory. Mathematical Association of America Textbooks. Vol. 24. The Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 9780883850008.