Maurice Ralph Hilleman (August 30, 1919 – April 11, 2005) was a leading American microbiologist who specialized in vaccinology and developed over 40 vaccines, an unparalleled record of productivity.[2][3][4][5][6] According to one estimate, his vaccines save nearly eight million lives each year.[3] He has been described as one of the most influential vaccinologists ever.[2][6][7][8][9][10] He has been called the "father of modern vaccines".[11][12] Robert Gallo called Hilleman "the most successful vaccinologist in history".[13] He has been noted by some researchers as having saved more lives than any other scientist in the 20th century.[14][15]

Maurice Hilleman | |

|---|---|

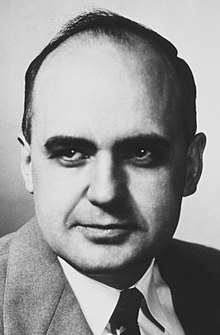

Hilleman c. 1958, as chief of the Dept. of Virus Diseases, Walter Reed Army Medical Center | |

| Born | Maurice Ralph Hilleman August 30, 1919 |

| Died | April 11, 2005 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Montana State University University of Chicago |

| Occupation(s) | Microbiologist, vaccinologist |

| Known for |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

Of the 14 vaccines routinely recommended in American vaccine schedules, Hilleman and his team developed eight: those for measles, mumps, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, chickenpox, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae bacteria.[4][7] During the influenza pandemic in Southern China, his vaccine is believed to have saved hundreds of thousands of lives.[7][15][16] He also played a key role in developing the vaccine for the Hong Kong flu.[7] He also played a role in the discovery of antigenic shift and drift, the cold-producing adenoviruses, the hepatitis viruses, and the potentially cancer-causing virus SV40.[3][6][17][18][19]

Biography

editEarly life and education

editHilleman was born on a farm near the high plains town of Miles City, Montana. His parents were Anna (Uelsmann) and Gustav Hillemann, and he was their eighth child.[20] His twin sister died on the day the twins were born, and his mother died two days later. He was raised in the nearby household of his uncle, Bob Hilleman, and worked in his youth on the family farm. He credited much of his success to his work with chickens as a boy; since the 1930s, fertile chicken eggs had often been used to grow viruses for vaccines.[4]

His family belonged to the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod. When he was in the eighth grade, he discovered Charles Darwin, and was caught reading On the Origin of Species in church. Later in life, he rejected religion.[21] Due to lack of funds, he almost failed to attend college. His eldest brother interceded, and Hilleman graduated first in his class in 1941 from Montana State University with family help and scholarships. He won a fellowship to the University of Chicago and received his doctoral degree in microbiology in 1944.[22] His doctoral thesis was on chlamydia infections, which were then thought to be caused by a virus. Hilleman showed that these infections were actually caused by a species of bacterium, Chlamydia trachomatis, that grows only inside of cells.[4]

Career

editAfter joining E.R. Squibb & Sons (now Bristol-Myers Squibb), Hilleman developed a vaccine against Japanese B encephalitis, a disease that threatened American troops in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. As chief of the Department of Respiratory Diseases at Army Medical Center (now the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research) from 1948 to 1957, Hilleman discovered the genetic changes that occur when the influenza virus mutates, known as antigenic shift and Antigenic drift, which he theorized would mean that a yearly influenza vaccination would be necessary.[2][23]

In 1957, Hilleman joined Merck & Co. (Kenilworth, New Jersey), as head of its new virus and cell biology research department in West Point, Pennsylvania. It was at Merck that Hilleman developed most of the forty experimental and licensed animal and human vaccines for which he is credited, working both at the laboratory bench as well as providing scientific leadership.

Hilleman served on many national and international advisory boards and committees, academic, governmental and private, including the National Institutes of Health's Office of AIDS Research Program Evaluation and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the National Immunization Program.[citation needed]

Asian flu pandemic

editHilleman was among the first to recognize that a 1957 outbreak of influenza in Hong Kong could become a huge pandemic. Working on a hunch, after nine 14-hour days he and a colleague determined that it was a new strain of flu that could kill millions.[6][24] Forty million doses of vaccines were prepared and distributed.[25] Although 69,000 Americans died, the pandemic could have resulted in many more deaths in the United States. Hilleman was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal from the American military for his work. His vaccine is believed to have saved hundreds of thousands of lives.[7][16]

In 1968, during the Hong Kong flu pandemic, Hilleman and his team also played a key role in developing a vaccine, and nine million doses became available in 4 months.[7][26]

SV40

editHilleman was one of the vaccine pioneers to warn about the possibility that simian viruses might contaminate vaccines.[27] The best-known of these viruses is SV40, a viral contaminant of the polio vaccine, whose discovery led to the recall of Salk's vaccine in 1961 and its replacement with Albert Sabin's oral vaccine. The contamination occurred in both vaccines at very low levels, but because the oral vaccine was ingested rather than injected, it did not result in any harm.[citation needed]

Mumps vaccine

editIn 1963, his daughter Jeryl Lynn came down with the mumps. He cultivated material from her, and used it as the basis of a mumps vaccine. The Jeryl Lynn strain of the mumps vaccine is still used. The strain is used in the trivalent (measles, mumps and rubella) MMR vaccine that he also developed, the first approved vaccine to incorporate multiple live virus strains. Like many other vaccines and medications of that time period, the vaccine was tested in children with intellectual disabilities who lived in group homes; this was because, given the poor hygiene and cramped quarters of their accommodations, they were at much higher risk of infectious disease.[28]

Hepatitis B vaccine

editHe and his group invented[4] a vaccine for hepatitis B by treating blood serum with pepsin, urea and formaldehyde. This was licensed in 1981, but withdrawn in 1986 in the United States and replaced by a vaccine that was produced in yeast. The latter vaccine is still in use. By 2003, 150 countries were using it and the incidence of the disease in the United States in young people had decreased by 95%. Hilleman considered his work on this vaccine to be his single greatest achievement. Liver transplant pioneer Thomas Starzl said "...controlling the hepatitis B virus scourge ranks as one of the most outstanding contributions to human health of the twentieth century...Maurice removed one of the most important obstacles to the field of organ transplantation".[29]

Later work and life

editIn his later life, Hilleman advised the World Health Organization. He retired as senior vice president of the Merck Research Labs in 1984 at its mandatory retirement age of 65. He then directed the newly created Merck Institute for Vaccinology where he worked for the next twenty years until his death in 2005.[30]

At the time of his death in Philadelphia on April 11, 2005,[21] at the age of 85, Hilleman was Adjunct Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Method and personality

editHilleman was a forceful man yet at the same time, modest in his claims. None of his vaccines or discoveries are named after him. He ran his laboratory like a military unit, and he was the one in command. For a time, he kept a row of "shrunken heads" (actually fakes made by one of his children) in his office as trophies representing each of his fired employees. He used profanity and tirades freely to drive his arguments home, and once, famously, refused to attend a mandatory "charm school" course intended to make Merck middle managers more civil. His subordinates were fiercely loyal to him.[4]: 128–131

Awards and honors

editHilleman was an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences,[31] the Institute of Medicine, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences,[32] and the American Philosophical Society.[33] In 1988, President Ronald Reagan presented him with the National Medal of Science, the nation's highest scientific honor. He received the Prince Mahidol Award from the King of Thailand for the advancement of public health, as well as a special lifetime achievement award from the World Health Organization, the Mary Woodard Lasker Award for Public Service and the Sabin Gold Medal and Lifetime Achievement Awards. In 1975, Hilleman received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[34]

Legacy

editIn March 2005, the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine's Department of Pediatrics and The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, in collaboration with The Merck Company Foundation, announced the creation of The Maurice R. Hilleman Chair in Vaccinology.[citation needed]

Robert Gallo, co-discoverer of HIV (the virus that causes AIDS), said in 2005: "If I had to name a person who has done more for the benefit of human health, with less recognition than anyone else, it would be Maurice Hilleman. Maurice should be recognized as the most successful vaccinologist in history."[8]

In 2005, Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that Hilleman's contributions were "the best kept secret among the lay public. If you look at the whole field of vaccinology, nobody was more influential."[2] In addition, Fauci said that "Hilleman is one of the true giants of science, medicine and public health in the 20th century. One can say without hyperbole that Maurice has changed the world."[7][35]

In 2007, Paul Offit published a biography of Hilleman, entitled Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases.[4]

In 2007, Anthony S. Fauci wrote in a biographical memoir of Hilleman:[7][36]

Maurice was perhaps the single most influential public health figure of the twentieth century, if one considers the millions of lives saved and the countless people who were spared suffering because of his work. Over the course of his career, Maurice and his colleagues developed more than forty vaccines. Of the fourteen vaccines currently recommended in the United States, Maurice developed eight.

In 2008, Merck named its Maurice R. Hilleman Center for Vaccine Manufacturing, in Durham, North Carolina, in memory of Hilleman.[37]

In 2009, the American Society of Microbiology (ASM) established the Maurice Hilleman/Merck Award in Vaccinology[38] to honor major contributions to pathogenesis, vaccine discovery, vaccine development, and/or control of vaccine-preventable diseases. The annual award was presented from 2008 to 2018. The first laureate was Stanley Plotkin. Subsequent awardees were Samuel L. Katz (2010), Albert Z. Kapikian (2011), Myron Levine (2012), Emil Gotschlich and R. Gwin Follis-Chevron (2013), Dan M. Granoff (2014), Peter Palese (2016) and Stephen Whitehead (2018)

In 2016, a documentary film titled Hilleman: A Perilous Quest to Save the World's Children, chronicling Hilleman's life and career, was released by Medical History Pictures, Inc.[39]

In 2016, Montana State University dedicated a series of scholarships in memory of its alumnus Hilleman, called the Hilleman Scholars Program,[40] for incoming students who "commit to work at their education beyond ordinary expectations and help future scholars that come after them".[41]

References

edit- ^ "About Dr. Hilleman". hillemanfilm.com.

- ^ a b c d Newman, Laura (2005-04-30). "Maurice Hilleman". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 330 (7498): 1028. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1028. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 557162.

- ^ a b c Dove, Alan (April 2005). "Maurice Hilleman". Nature Medicine. 11 (4): S2. doi:10.1038/nm1223. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 15812484. S2CID 13028372.

- ^ a b c d e f g Offit, Paul A. (2007). Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases. Washington, DC: Smithsonian. ISBN 978-0-06-122796-7.

- ^ "Maurice Hilleman". www.telegraph.co.uk. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ a b c d "Maurice Ralph Hilleman (1919–2005) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia". Arizona State University. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World". Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 9780128045718. PMC 7150172.

- ^ a b Maugh, Thomas H. II (2005-04-13). "Maurice R. Hilleman, 85; Scientist Developed Many Vaccines That Saved Millions of Lives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ^ "Dr. Maurice Hilleman: "The father of modern vaccines"". Merck.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ Levine, Myron M.; Gallo, Robert C. (2005). "A Tribute to Maurice Ralph Hilleman". Human Vaccines. 1 (3): 93–94. doi:10.4161/hv.1.3.1967. S2CID 71919247.

- ^ "The Unknown (Vaccine) Hero: Dr. Maurice Hilleman | Immunize Nevada". www.immunizenevada.org. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- ^ Winston-Macauley, Marnie (2022-11-20). "This Doctor Saved Tens of Millions of Lives, Yet Few Know his Name". Aish.com. Retrieved 2023-12-12.

- ^ II, Thomas H. Maugh (2005-04-13). "Maurice R. Hilleman, 85; Scientist Developed Many Vaccines That Saved Millions of Lives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Reed, Christopher (2005-04-14). "Maurice Hilleman". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ a b Simpson, J. Cavanaugh (2020-04-19). "The Man Who Beat the 1957 Flu Pandemic". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ a b Offord, Catherine (2020-06-01). "Confronting a Pandemic, 1957". The Scientist Magazine. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ Kurth, Reinhard (April 2005). "Maurice R. Hilleman (1919–2005)". Nature. 434 (7037): 1083. doi:10.1038/4341083a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15858560. S2CID 26364385.

- ^ Oransky, Ivan (2005-05-14). "Maurice R Hilleman". The Lancet. 365 (9472): 1682. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66536-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 15912596. S2CID 46630955.

- ^ Poulin, D. L.; Decaprio, J. A. (2006). "Is There a Role for SV40 in Human Cancer?". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (26): 4356–65. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7101. PMID 16963733.

- ^ "World Who's who in Science: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Scientists from Antiquity to the Present". 1968.

- ^ a b "Maurice Hilleman". The Independent. April 19, 2005. Archived from the original on 2022-05-12. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Newman, L. (2005). "Maurice Hilleman". BMJ. 330 (7498): 1028. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1028. PMC 557162.

- ^ Offit, Paul A (2008). Vaccinated : one man's quest to defeat the world's deadliest diseases (1st Smithsonian books paperback ed.). [Washington, D.C.]: Smithsonian Books. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-06-122796-7. OCLC 191245549.

- ^ Simpson, J. Cavanaugh. "The Man Who Beat the 1957 Flu Pandemic". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ "This virologist saved millions of children—and stopped a pandemic". National Geographic. 2020-05-29. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ "Vaccine for Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic". History of Vaccines. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ Bookchin D, Schumacher J (2004). The Virus and the Vaccine. St. Martin's Press. pp. 94–98. ISBN 0-312-27872-1.

- ^ Offit, Paul (2008). Vaccinated : one man's quest to defeat the world's deadliest diseases (1st Smithsonian books paperback ed.). [Washington, D.C.]: Harper Collins. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-06-122796-7. OCLC 191245549.

- ^ Offit, Paul (2007). Vaccinated : one man's quest to defeat the world's deadliest diseases (1st Smithsonian books paperback ed.). [Washington, D.C.]: Smithsonian Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-06-122796-7. OCLC 191245549.

- ^ Levine, Myron M.; Gallo, Robert C. (2005-05-23). "A Tribute to Maurice Ralph Hilleman". Human Vaccines. 1 (3): 93–94. doi:10.4161/hv.1.3.1967. ISSN 1554-8600. S2CID 71919247.

- ^ "Maurice R. Hilleman". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ "Maurice Ralph Hilleman". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Maurice R. Hilleman, 85; Scientist Developed Many Vaccines That Saved Millions of Lives". Los Angeles Times. 2005-04-13. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S. (2007). "Maurice R. Hilleman, 30 August 1919 · 11 April 2005". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 151 (4): 451–455. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 25478459.

- ^ "Merck & Co., Inc., Dedicates Durham Vaccine Manufacturing Facility in Honor of Merck Scientist Maurice R. Hilleman, Ph.D." Business Wire. Berkshire Hathaway. October 15, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "Maurice Hilleman/Merck Award" (PDF). 30 January 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Hilleman – A Perilous Quest to Save the World's Children". hillemanfilm.com. Vaccine Education Center at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ "MSU Hilleman Scholars Program". Montana State University. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ MSU News Service. "MSU inaugurates Hilleman Scholars Program for Montanans in honor of world's most famous vaccinologist". Montana State University. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

External links

edit- Hilleman – A Perilous Quest to Save the World's Children (a documentary about his life)