MacConkey agar is a selective and differential culture medium for bacteria. It is designed to selectively isolate gram-negative and enteric (normally found in the intestinal tract) bacteria and differentiate them based on lactose fermentation.[1] Lactose fermenters turn red or pink on MacConkey agar, and nonfermenters do not change color. The media inhibits growth of gram-positive organisms with crystal violet and bile salts, allowing for the selection and isolation of gram-negative bacteria. The media detects lactose fermentation by enteric bacteria with the pH indicator neutral red.[2]

Contents

editIt contains bile salts (to inhibit most gram-positive bacteria), crystal violet dye (which also inhibits certain gram-positive bacteria), and neutral red dye (which turns pink if the microbes are fermenting lactose).

Composition:[3]

- Peptone – 17 g

- Proteose peptone – 3 g

- Lactose – 10 g

- Bile salts – 1.5 g

- Sodium chloride – 5 g

- Neutral red – 0.03 g

- Crystal violet – 0.001 g

- Agar – 13.5 g

- Water – add to make 1 litre; adjust pH to 7.1 +/− 0.2

- Sodium taurocholate

There are many variations of MacConkey agar depending on the need. If the spreading or swarming of Proteus species is not required, sodium chloride is omitted. Crystal violet at a concentration of 0.0001% (0.001 g per litre) is included when needing to check if gram-positive bacteria are inhibited. MacConkey with sorbitol is used to isolate E. coli O157, an enteric pathogen.[4]

History

editThe medium was developed by Alfred Theodore MacConkey while working as a bacteriologist for the Royal Commission on Sewage Disposal. [5]

Uses

editUsing neutral red pH indicator, the agar distinguishes those gram-negative bacteria that can ferment the sugar lactose (Lac+) from those that cannot (Lac-).

This medium is also known as an "indicator medium" and a "low selective medium". Presence of bile salts inhibits swarming by Proteus species.

Lac positive

editBy utilizing the lactose available in the medium, Lac+ bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter and Klebsiella will produce acid, which lowers the pH of the agar below 6.8 and results in the appearance of pink colonies. The bile salts precipitate in the immediate neighborhood of the colony, causing the medium surrounding the colony to become hazy.[6][7]

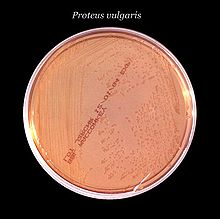

Lac negative

editOrganisms unable to ferment lactose will form normal-colored (i.e., un-dyed) colonies. The medium may also turn yellow. Examples of non-lactose fermenting bacteria include Salmonella, Proteus, and Shigella spp.[4]

Slow

editSome organisms ferment lactose slowly or weakly, and are sometimes put in their own category. These include Serratia[8] and Citrobacter.[9]

Mucoid colonies

editSome organisms, especially Klebsiella and Enterobacter, produce mucoid colonies which appear very moist and sticky and slimy. This phenomenon happens because the organism is producing a capsule, which is predominantly made from the lactose sugar in the agar.

Variant

editA variant, sorbitol-MacConkey agar, (with the addition of additional selective agents) can assist in the isolation and differentiation of enterohemorrhagic E. coli serotype O157:H7, by the presence of colorless circular colonies that are non-sorbitol fermenting.[4]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "MacConkey Agar". Texas Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2008-11-04.

- ^ Anderson, Cindy (2013). Great Adventures in the Microbiology Laboratory (7th ed.). Pearson. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1-269-39068-2.

- ^ "MacConkey Agar Plates Protocols". Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- ^ a b c Doern, Christopher D. (2018). Pocket Guide to Clinical Microbiology (4th ed.). ASM Press. p. 149. ISBN 9781683670063.

- ^ Smith, Kenneth (2019-10-14). "The Origin of MacConkey Agar". American Society for Microbiology. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ MacConkey AT (1905). "Lactose-Fermenting Bacteria in Faeces". J Hyg (Lond). 5 (3): 333–79. doi:10.1017/s002217240000259x. PMC 2236133. PMID 20474229.

- ^ MacConkey AT (1908). "Bile Salt Media and their advantages in some Bacteriological Examinations". J Hyg (Lond). 8 (3): 322–34. doi:10.1017/s0022172400003375. PMC 2167122. PMID 20474363.

- ^ Luis M. De LA Maza; Pezzlo, Marie T.; Janet T. Shigei; Peterson, Ellena M. (2004). Color Atlas of Medical Bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. p. 103. ISBN 1-55581-206-6.

- ^ "Medmicro Chapter 26". Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2008-12-11.