Me and Orson Welles is a 2008 period drama film directed by Richard Linklater and starring Zac Efron, Christian McKay, and Claire Danes. Based on Robert Kaplow's novel of the same name, the story, set in 1937 New York, tells of a teenager hired to perform in Orson Welles's groundbreaking stage adaptation of William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar who becomes attracted to a career-driven production assistant.

| Me and Orson Welles | |

|---|---|

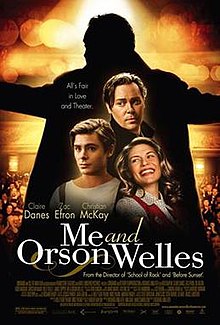

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Linklater |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Me and Orson Welles by Robert Kaplow |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dick Pope |

| Edited by | Sandra Adair |

| Music by | Michael J McEvoy |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 113 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[3] |

| Box office | $2.3 million[3] |

The film was shot in London and New York and on the Isle of Man in February, March and April 2008, and was released in the United States on November 25, 2009, and the United Kingdom on December 4, 2009.

McKay's portrayal of Welles was recognized with a multitude of accolades, and Me and Orson Welles was named one of the top ten independent films of the year by the National Board of Review.

Plot

editIn New York City in the fall of 1937, 17-year-old high-school student Richard Samuels meets Orson Welles, who unexpectedly offers him the role of Lucius in Caesar, the first production of his new Mercury Theatre repertory company. The company is immersed in rehearsals at its Broadway theater. Charmed by Welles, Richard learns that he is having an affair with the leading actress while his wife is pregnant. Richard finds ambitious production assistant Sonja Jones is attracted to him.

Welles tells Richard a few days before the premiere that he is worried, because he has recently had nothing but good luck; he fears that he will finally have bad luck with the premiere, and that the play will be a flop. During rehearsals Richard sets off the sprinkler system, soaking the entire theatre. When accused by Welles he denies having anything to do with the deluge, and suggests that the catastrophe was the bad luck that Welles needed to get out of the way.

Welles decides the entire production crew would benefit from a coupling game, and Richard cheats to ensure he is paired with Sonja. Richard spends the night with Sonja, but becomes jealous when she spends the next night with Welles. He confronts Welles, mentions his pregnant wife, and is fired. An apparent reconciliation follows, and Richard performs on the first night. The anti-fascist adaptation of Caesar is a huge success, but after the premiere, Richard is told that Welles only needed him in order to secure a successful first-night production and, that done, he has again been fired.

The broken-hearted but wiser Richard spontaneously recites lines from Julius Caesar in his high school English class, to his classmates' applause. He later meets up with a likely new girlfriend, Gretta Adler, a young aspiring playwright whom he met in a music store at the film's beginning. With Richard's and Sonja's assistance, Adler manages to get a story published in The New Yorker, and she invites Richard out, to help her celebrate.

Cast

edit- Zac Efron as Richard Samuels

- Christian McKay as Orson Welles

- Claire Danes as Sonja Jones

- Ben Chaplin as George Coulouris

- James Tupper as Joseph Cotten

- Eddie Marsan as John Houseman

- Leo Bill as Norman Lloyd

- Kelly Reilly as Muriel Brassler

- Patrick Kennedy as Grover Burgess

- Travis Oliver as John Hoyt

- Zoe Kazan as Gretta Adler

- Al Weaver as Sam Leve

- Saskia Reeves as Barbara Luddy

- Imogen Poots as Lorelei Lathrop

- Rhodri Orders as Stefan Schnabel

- Michael Brandon as Les Tremayne

- Janie Dee as Mrs Samuels

- Jo McInnes as Jean Rosenthal

- Aidan McArdle as Martin Gabel

Production

editHolly Gent and Vincent Palmo Jr. adapted the film's screenplay from Robert Kaplow's novel of the same name about a teenager (in reality, the 15-year-old Arthur Anderson, who played Lucius in Welles' production[4]) involved in the founding of Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre.[5] After receiving funding from CinemaNX, a production company backed by the Isle of Man film fund, and an offer from Framestore Features to co-finance the film, Richard Linklater came on board to direct Me and Orson Welles.[5] Zac Efron signed on as the lead in early January 2008,[6] claiming he decided to take the role of Richard Samuels because "It's a completely different project than I've ever done before,"[7] while Claire Danes joined the cast as the protagonist's love interest Sonja Jones in late January.[5]

In the theatre, Christian McKay had portrayed Orson Welles in the one-man play Rosebud: The Lives of Orson Welles at a number of venues, including the Edinburgh Festival[8] and King's Head (London).[9] He reprised the role in the U.S. at the 2007 "Brits Off Broadway" festival,[10] where Linklater saw his performance and then cast McKay as Welles, retaining him over the subsequent objections of the project's producer.[11]

| "We went in at the deep end by taking Richard Linklater's Me and Orson Welles out of New York to shoot on the Isle of Man and at Pinewood. With the dollar rate fairly consistent at 2 to 1 against us, we really did show that we could put together a competitive financing and producing package." |

| — CinemaNX chairman Steve Christian[12] |

Me and Orson Welles underwent filming in the Isle of Man, Pinewood Studios, London and New York from February to April 2008.[13] Filming in London commenced first in mid-February,[7] before scenes in the Isle of Man were shot February 24 – March 14, 2008, where filming locations included Gaiety Theatre and various other parts of Douglas.[14][15] During filming in Douglas, Efron and Danes believe they sighted a ghost, or "supernatural" being, outside a window on set at Gaiety Theatre.[16]

Filming in Britain resumed in late March for six weeks at Pinewood Studios.[17] Other locations included Crystal Palace Park, where a façade of New York's Mercury Theatre was set up for a scene.[18] Actor James Tupper claimed that the best replica of an old New York theater was in England, while many of the actors who filled the company were from the Royal Shakespeare Company.[17] The production crew only briefly visited New York; photographs were taken and footage shot to be added into the film as digital effects. Every exterior shot was filmed on a single street built at Pinewood Studios with a green screen at one end; different angles and slightly altered set designs were used between shots to make the street appear different each time.[19]

Release

editSelect footage of Me and Orson Welles was screened at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival[20] where financing and sales agency Cinetic Media were looking to sell the film to a distributor.[21] Before its Cannes premiere, The Hollywood Reporter predicted that the film would attract distributors with Linklater's résumé and Efron's teen "heartthrob" status to appeal to a younger demographic,[22] but Me and Orson Welles failed to secure any American acquisitions.[20] Its first full screening was at the 2008 Toronto International Film Festival, running September 4–13, 2008.[23] In spite of its failure to find a buyer at Cannes, Toronto's co-director Cameron Bailey predicted that it would be "one of the hottest films" in the lineup,[24] Anne Thompson of Variety magazine also believed that the film would be one of "only a few lucky winners" to secure a seven-figure deal.[25]

Again, however, the film's distribution rights were not purchased and it went on to show at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas.[26] In May 2009, production company CinemaNX announced that it would distribute Me and Orson Welles itself, sharing marketing and advertising costs with Vue Entertainment.[27] Freestyle Releasing was hired as the US distributor with Hart/Lunsford Pictures in exchange for participation in revenues paid the $4 million prints and advertising cost.[1]

It was screened at the Woodstock Film Festival in September 2009, where Linklater was honored as the winner of the 2009 Maverick Award.[28] it opened the New Orleans Film Festival on October 9, 2009;[29] and it was screened at the St. Louis International Film Festival in November 2009.[30]

The film was released in the US on November 25, 2009,[31] and in the UK on December 4, 2009.[32] IndieWIRE reported, "The do-it-yourself release of Richard Linklater's Me and Orson Welles got off to a very nice start, averaging $15,910 from its four theaters, the highest PTA of all debuting films. ... While Orson Welles is one of the first examples of such a high-profile film going to the DIY route, if it proves successful, it's going to be done a lot more in the future."[33]

Reception

editBox office

editDuring its theatrical release (November 25, 2009 – February 25, 2010), Me and Orson Welles grossed a total of $1,190,003 in the United States and $2,336,172 worldwide.[3]

Critical response

editThe film has received positive reviews from critics. It currently holds an 85% positive rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 156 critic reviews, with an average rating of 7.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Me and Orson Welles boasts a breakout performance by Christian McKay and an infectious love of the backstage drama that overcomes its sometimes fluffy tone."[34] It holds a weighted average score of 73 out of 100 on Metacritic from 30 critics.[35]

Film critic Roger Ebert called Me and Orson Welles "one of the best movies about the theater I've ever seen ... not only entertaining but an invaluable companion to the life and career of the Great Man".[36] Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter praised the film for its "terrific acting" and called it "a must for lovers and students of the theater".[37] Variety magazine's Todd McCarthy labelled McKay's performance "an extraordinary impersonation" of Welles, though he wrote that "Efron never feels like a proper fit for Richard".[38] Karen Durbin of The New York Times praised McKay in the Welles role, saying he brought "a watchful, assessing and subtly excited gaze that makes him thrilling and a little dangerous."[39]

"I've never seen a backstage movie that was truer to the experience of putting on a show," wrote Wall Street Journal drama critic Terry Teachout, who reserved special praise for the design team's recreation of Welles's production of Julius Caesar:[40]

Like most Welles stage shows, alas, this one left few traces. No part of the production was filmed, and nothing else survives but the design sketches and some still photographs taken in 1937. ... What makes Me and Orson Welles uniquely interesting to scholars of American drama is that Mr. Linklater's design team found the Gaiety Theatre on the Isle of Man. This house closely resembles the old Comedy Theatre on 41st Street, which was torn down five years after Julius Caesar opened there. Using Samuel Leve's original designs, they reconstructed the set for Julius Caesar on the Gaiety's stage. Then Mr. Linklater filmed some 15 minutes' worth of scenes from the play, lit according to Jean Rosenthal's plot, accompanied by Marc Blitzstein's original incidental music and staged in a style as close to that of the 1937 production as is now possible.[40]

Teachout wrote that he "was floored by the verisimilitude of the results", and that "you will never get any closer to the Welles Julius Caesar than by watching Me and Orson Welles, whose DVD version also includes a special feature comprising footage of the reconstructed scenes, not all of which made the final cut."[40]

In 2015, Mercury actor Norman Lloyd (who is portrayed by Leo Bill in the film) praised Christian McKay's performance as Orson Welles as "the best rendition of him I've ever seen." However, he otherwise "hated" the film and he criticized the accuracy of the characters: "It bears no relation to truth, or to what happened when you worked with Orson and so forth. I thought McKay was very good, but the rest of the characters are just ridiculous. They're all made up! I didn't even recognize myself ... and then I thought, Well, thank goodness I can't!" Lloyd named George Coulouris as an example, who was shown as "neurotic and afraid to do his scene", while in reality he was someone "you couldn't stop from acting, for Christ's sake!".[41]

Accolades

editMe and Orson Welles was named one of the top ten independent films of 2009 by the National Board of Review.[42] It was listed as one of the year's top ten films by critics including Philip French of The Observer, David Denby of The New Yorker, and Michael Phillips and A. O. Scott of At the Movies.[43]

The film earned two awards from the Austin Film Critics Association – the Austin Film Award to director Richard Linklater. and the Breakthrough Artist Award to Christian McKay.[44] McKay received many accolades for his portrayal of Orson Welles, including Best Supporting Actor awards from the San Francisco Film Critics Circle and the Utah Film Critics Association. He received a BAFTA nomination for Best Supporting Actor,[45] and Best Supporting Actor nominations from the Boston Society of Film Critics (second place),[46] Broadcast Film Critics Association,[47] Chicago Film Critics Association,[48] Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association, Denver Film Critics Society, Detroit Film Critics Society,[49] Houston Film Critics Society,[50] International Cinephile Society,[51] National Society of Film Critics,[52] New York Film Critics Circle (second place),[53] Online Film & Television Association,[54] Toronto Film Critics Association,[55] and in the Chlotrudis Awards,[56] Independent Spirit Awards[57] and the Village Voice Film Poll (second place).[58] McKay was nominated in the Best Actor category in the Evening Standard British Film Awards,[59] London Critics Circle Film Awards and 2009 San Diego Film Critics Society Awards.

Home media

editOn August 17, 2010, Warner released Me and Orson Welles on DVD (ISBN 1-4198-9754-3) for exclusive sale at Target in the United States.[60] Entertainment One Films released the DVD in Canada on the same date.[61] The film has not been released on Blu-ray in the U.S., though it is available in the format in Italy and Germany.[citation needed]

Soundtrack

editThe original motion picture soundtrack for Me and Orson Welles was released on CD November 24, 2009, by Decca Records (5323762).[62]

- "This Year's Kisses", Benny Goodman and His Orchestra

- "I'm Shooting High", Louis Armstrong and His Orchestra

- "Sing, Sing, Sing", Benny Goodman and His Orchestra

- "One O'Clock Jump", Count Basie and His Orchestra

- "Ode to Krupa", Michael J McEvoy

- "Let's Pretend There's a Moon", Jools Holland and His Rhythm and Blues Orchestra featuring Eddi Reader

- "Let's Pretend There's a Moon", Christian McKay

- "Let Yourself Go", Ginger Rogers

- "Solitude", The Mills Brothers

- "Aftershow Jam", Michael J McEvoy featuring Huw Morgan on trumpet

- "They Can't Take That Away from Me", Fred Astaire

- "In a Sentimental Mood" (Instrumental), Benny Goodman and His Orchestra

- "The Music Goes Round and Round", Tommy Dorsey and His Clambake Seven

- "I Surrender Dear", Jools Holland and His Rhythm and Blues Orchestra featuring Eddi Reader

- "You Made Me Love You", Jools Holland and His Rhythm and Blues Orchestra featuring Eddi Reader

- "Have You Met Miss Jones?", James Langton and His Solid Senders

- "Sing, Sing, Sing", James Langton and His Solid Senders

References

edit- ^ a b Goldstein, Patrick (September 16, 2009). "The Big Picture". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ "Me and Orson Welles (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. July 9, 2009. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Me and Orson Welles (2009)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Byrnes, Paul (July 31, 2010). "Me and Orson Welles". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c Dawtrey, Adam (January 31, 2008). "Claire Danes joins Linklater film". Variety. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ "Zac Efron in 'Me and Orson Welles'". Entertainment Weekly. January 18, 2008. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Adler, Shawn (February 7, 2008). "Zac Efron Gets Serious For 'Orson Welles And Me'". MTV News. MTV. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Gardner, Lyn (August 17, 2004). "Rosebud (Assembly Rooms, Edinburgh)". The Guardian. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Costa, Maddy (January 9, 2006). "Rosebud (King's Head, London)". The Guardian. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Bellafante, Gina (June 6, 2007). "Finding Room for an Actor Fit for the Stage". The New York Times. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Clarke, Cath (October 15, 2009). "First sight: Christian McKay". The Guardian. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (May 18, 2008). "CinemaNX boards trio". Variety. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Richards, Olly (February 1, 2008). "Claire Danes, Me And Orson Welles". Empire. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ "Actor James Tupper to sample Isle of Man scenery". Isle of Man Today. Johnston Press. March 10, 2008. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ "Me and Orson Welles". Government of the Isle of Man. 2008. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Fletcher, Alex (March 13, 2008). "Efron scared by ghost on 'Orson Welles'". Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Schaefer, Glen (July 8, 2008). "James Tupper comes down from the Trees". The Gazette. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ Lee, Cara (April 4, 2008). "Film makers find Crystal Palace Park to be the perfect setting". Croydon Guardian. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (October 16, 2008). "Director P.O.V.: Richard Linklater". Variety. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Anthony (May 27, 2008). "Weak U.S. Market Reflected at Cannes". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (May 20, 2008). "Buyers proceed with caution at Cannes". Variety. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg; Zeitchik, Steven (May 16, 2008). "Tasty titles tempt Cannes buyers". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ Garcia, Chris (August 13, 2008). "Linklater's latest at Toronto". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ^ Knegt, Peter (August 19, 2008). "Toronto Co-Director Cameron Bailey". IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (August 21, 2008). "Independents change tactics". Variety. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- ^ Garcia, Chris (March 18, 2009). "Linklater's new film to screen at SXSW". Austin American-Statesman. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ Kemp, Stuart (May 14, 2009). "CinemaNX signs 3-pic deal with Vue". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ Lussier, Germain (April 29, 2009). "Richard Linklater named 2009 Maverick Award winner by the Woodstock Film Festival". Times Herald-Record. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Scott, Mike (November 16, 2009). "New Orleans Film Festival lineup to feature bold-faced names". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ Hudson, David (September 16, 2009). ""Me and Orson Welles" and "The Road"". MUBI. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ Riemer, Emily (September 10, 2009). "Richard Linklater Gets Long-Awaited Release Date for Orson Welles Biopic". Paste. Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ "December Release for "Me and Orson Welles" in UK Cinemas". Isle of Media. July 31, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Knegt, Peter (December 2, 2009). "Box Office 2.0: The Curious Case of "Orson Welles"". IndieWire. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Me and Orson Welles (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "Me and Orson Welles Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 9, 2009). "The artist as a young ego". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (September 6, 2008). "Film Review: Me and Orson Welles". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (September 6, 2008). "Film Review: Me and Orson Welles". Variety. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Durbin, Karen (September 10, 2009). "Dazzling Performances to Gild the Résumés". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c Teachout, Terry (October 29, 2010). "Relishing a Lost Production". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ Harris, Will (November 5, 2015). "Norman Lloyd on upstaging Orson Welles and playing tennis with Chaplin". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "2009 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ French, Lawrence (January 16, 2010). "Christian McKay wins the Wellesnet Award for Best Supporting Actor". Wellesnet. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "2009 Awards". Austin Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Me & Orson Welles Scoops Major Bafta Nomination - Isle of Man Film Press Release". Visit Isle of Man. Isle of Man Government. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Boston film critics speak". Boston.com. December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (December 14, 2009). "'Basterds,' 'Nine' lead Critics' Choice noms". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Chicago Film Critics Awards - 2008-". Chicago Film Critics. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Detroit Film Critics Announces Nominations". IndieWire. December 12, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Dansby, Andrew (December 18, 2009). "Houston critics judging films". Chron. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Stevens, Beth (June 14, 2010). "2010 ICS Award Nominees". International Cinephile Society. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Knegt, Peter (January 3, 2010). ""Locker" Tops National Society of Film Critics". IndieWire. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Oscar Watch: NY, LA critics boost 'Hurt Locker'". New York Post. December 15, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "14th Annual Film Awards (2009) - Online Film & Television Association". Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "Toronto Film Critics Association Awards 2009". Toronto Film Critics. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "2010, 16th Annual Awards, March 21, 2010". Chlotrudis Society for Independent Film. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "2010 Indie Film Spirit Award Nominations". Deadline Hollywood. December 1, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Village Voice (December 22, 2009). "10th Annual Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Evening Standard British Film Awards". Awards Daily. February 8, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Kane, Mondo (July 6, 2010). "Aug 17 - Target exclusive: ME AND ORSON WELLES on DVD (Warner Bros.)". DVD Town. Archived from the original on July 9, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ^ "Entertainment One Home Video". Archived from the original on July 10, 2011.

- ^ "Me & Orson Welles – Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. RhythmOne. Retrieved July 15, 2014.