The Metropolitanate of Karlovci (Serbian: Карловачка митрополија, romanized: Karlovačka mitropolija) was a metropolitanate of the Eastern Orthodox Church that existed in the Habsburg monarchy between 1708 and 1848.[1] Between 1708 and 1713, it was known as the Metropolitanate of Krušedol, and between 1713 and 1848, as the Metropolitanate of Karlovci. In 1848, it was elevated to the Patriarchate of Karlovci, which existed until 1920, when it was merged with the Metropolitanate of Belgrade and other Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions in the newly established Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to form the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Metropolitanate of Karlovci Карловачка митрополија Karlovačka mitropolija | |

|---|---|

Coat of Arms of Metropolitanate of Karlovci | |

| Location | |

| Territory | Habsburg monarchy |

| Headquarters | Karlovci, Habsburg monarchy (modern Sremski Karlovci, Serbia) |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Eastern Orthodox |

| Sui iuris church | Self-governing Eastern Orthodox Metropolitanate |

| Established | 1708 |

| Dissolved | 1848 |

| Language | Church Slavonic Slavonic-Serbian |

History

editDuring the 16th and 17th centuries, all of the southern and central parts of the former medieval Kingdom of Hungary were under Turkish rule and organized as Ottoman Hungary. Since 1557, Serbian Orthodox Church in those regions was under jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć. During the Austro-Turkish War (1683–1699), much of the central and southern Hungary was liberated and Serbian eparchies in those regions fell under the Habsburg rule. In 1689, Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III Crnojević sided with Austrians, and moved from Peć to Belgrade in 1690, leading the Great Migration of the Serbs. In that time, a large number of Serbs migrated to southern and central parts of Hungary.[2][3]

Important privileges were given to them by Emperor Leopold I in three imperial chapters (Diploma Leopoldinum) the first issued on 21 August 1690, the second a year later, on 20 August 1691, and the third on 4 March 1695.[4] Privileges allowed Serbs to keep their Eastern Orthodox faith and church organization headed by archbishop and bishops. In next two centuries of its autonomous existence, autonomous Serbian Church in Habsburg monarchy was organized on the basis of privileges originally received from the emperor.[5] As the Serb settlers were granted religious freedom and eclestical autonomy without separate diet, the Metropolitanate of Karlovci developed not only into religious but also quasi-political institution with its assembly effectively functioning as a Serb estates diet.[6]

Creation and reorganization (1708–1748)

editUntil death in 1706, head of the church was Patriarch Arsenije III who reorganized eparchies and appointed new bishops. He held the title of Serbian Patriarch until the end of his life. New emperor Joseph I (1705–1711), following the advice of Cardinal Leopold Karl von Kollonitsch abolished that title, and substitute it with less distinguished title of archbishop or metropolitan. In his decree, Emperor Joseph I stated, "we must make sure that they never elect another Patriarch since it is against the Catholic Church and the doctrine of the Fathers of the Church". According to that, future primates of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the new Kingdom of Serbia of the Habsburg Monarchy will bare the title of archbishop and metropolitan. The only exception from the Imperial decree was the case of later Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta (1725–1748) who brought his title directly from the historic see of Peć (1737).[7]

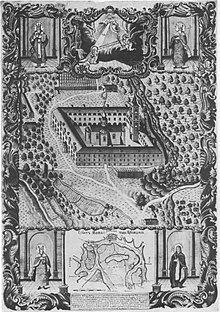

After the death of Patriarch Arsenije III (1706), the Serbian Church Council was held in the Krušedol Monastery in 1708 and proclaimed Krušedol to be the official cathedral seat of the newly elected Archbishop and Metropolitan Isaija Đaković, while all administrative activities were moved to the nearby city of Sremski Karlovci. The Krušedol Monastery was bequest of the late medieval Serbian Branković dynasty in the beginning of the 16th century, which was the main historical and national reason for the Serbs to choose this monastery as their Church capital.[8]

Between 1708 and 1713, the seat of the Metropolitanate was in the Krušedol Monastery, and in 1713 it was moved to Karlovci (modern Sremski Karlovci, Serbia). The new archbishop Vikentije Popović-Hadžilavić (1713–1725) moved all administration from Krušedol to Karlovci.[1] So, the new capital of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Habsburg Monarchy became Sremski Karlovci which was confirmed by the seal of Imperial approval in the charter of Emperor Charles VI issued in October the same year.

During the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718), regions of Lower Syrmia, Banat, central Serbia with Belgrade, and Oltenia were liberated from Ottoman rule, and under the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718) became part of the Habsburg Monarchy.[9] Political change was followed by ecclesiastical reorganization. Eparchies in newly liberated regions were not subjected to the Metropolitan of Karlovci, mainly because Habsburg authorities did not want to allow the creation of unified and centralized administrative structure of the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Monarchy. Instead of that, they supported the creation of a separate metropolitanate for Eastern Orthodox Serbs and Romanians in liberated regions, centered in Belgrade. The newly created Metropolitanate of Belgrade was headed by metropolitan Mojsije Petrović (d. 1730). New autonomous Metropolitanate of Belgrade had jurisdiction over Kingdom of Serbia (Belgrade was the capital city) and Banat, and also over Oltenia.[10]

The creation of new metropolitan province was approved by Serbian Patriarch Mojsije I (1712–1725), who also recommended future unification. Shortly after, two metropolitanates did merge, in 1726, and by the imperial decree of Charles VI, the administrative capital of Serbian Orthodox Church was moved from Sremski Karlovci to Belgrade in 1731. Metropolitan Vikentije Jovanović (1731–1737) resided in Belgrade.[11]

During the Austro-Turkish War (1737–1739), Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta (1725–1748) sided with the Habsburgs and in 1737 left Peć and came to Belgrade, taking over the administration of the Metropolitanate. He received imperial confirmation, and when Belgrade fell to Ottomans in the autumn of 1739, he moved the church headquarters to Sremski Karlovci.

Consolidation of the Metropolitanate (1748–1848)

editIn 1748, patriarch Arsenije IV died, and church council was held for the election of a new primate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the Habsburg Monarchy. After the short tenure of metropolitan Isaija Antonović (1748–1749), another church council was held, electing the new metropolitan Pavle Nenadović (1749–1768).[12] During his tenure important administrative reforms were undertaken in the Metropolitanate of Karlovci. He also tried to help the patriarchal mother-church in Peć, under the Ottoman rule, but the old Serbian Patriarchate could not be saved. In 1766, the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was finally abolished, and all of its eparchies that were under Turkish rule were overtaken by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. Serbian hierarchs of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci had no intention to submit themselves to the Greek Patriarch in Constantinople, and the Ecumenical Patriarchate also had enough wisdom not to demand their submission. From that time, Metropolitanate of Karlovci continued functioning as the fully independent ecclesiastical center of Eastern Orthodoxy in the Habsburg Monarchy, with seven suffragan bishops (Bačka, Vršac, Temišvar, Arad, Buda, Pakrac and Upper Karlovac).[13]

The position of Serbs and their Church in Habsburg Monarchy was further regulated by reforms brought about by Dowager-Empress Maria Theresa, Queen of Hungary (1740–1780). The Serbian Church Council of 1769 regulated various issues in a special act named "Regulament" and, later, in similar act called the Declaratory Rescript of the Illyrian Nation, published in 1779.[5] The death of Maria Theresa in 1780 marked the end the old imperial and royal House of Habsburg, highly respected among Orthodox Serbs, and succession passed to the new dynasty, called the House of Habsburg-Lorraine that ruled until 1918. Enlightened reforms of emperor Joseph II (1780–1790) affected all religious institutions in the Monarchy, including the Metropolitanate of Karlovci.

Serbian metropolitans of Sremski Karlovci promoted the Enlightenment by introducing western education in the schools established in Sremski Karlovci (1733), and in Novi Sad (1737). In order to counter the Roman Catholic influence, the school curricula was exposed to cultural influence of the Russian Orthodox Church. As early as in 1724 the Holy Synod of Russian Orthodox Church sent M. Suvorov to open a school in Sremski Karlovci, which graduates were thereof passed on to Kievan seminary, and the more gifted to the Academy in Kiev.[14] The Church liturgical language became Russian Slavonic, called the New Church Slavonic. On another hand, Baroque influence became visible in the church architecture, iconography, literature and theology.[15]

During the eighteenth century the Metropolitanate maintained close connections with Kiev and the Russian Orthodox Church. Many Serbian theological students were educated in Kiev. A Seminary was open in 1794 which educated Orthodox priests during the nineteenth century for the needs of the Karlovci Metropolitanate and beyond.[5]

By the end of the 18th century, the Metropolitanate of Karlovci included a large territory that stretched from the Adriatic Sea to Bukovina and from Danube and Sava to Upper Hungary. During the long tenure of highly conservative metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović (1790–1836),[16] internal reforms were halted, resulting in the gradual formation of two fractions that would subsequently mark the life of Orthodox Serbs in the Metropolitanate, and later Patriarchate of Karlovci throughout the 19th century. First fraction was clerical and conservative. It was led by majority of bishops and higher clergy. Second fraction was oriented towards further reforms within the church administration, in order to allow more influence on decision making to lower clergy, laity and civil leaders. In the same time, aspirations towards Serbian national autonomy within the Empire gained great importance, leading to historical events of 1848–49.[17]

Eparchies under direct or spiritual jurisdiction of Karlovci

editThe Metropolitanate included the following eparchies:

| Eparchy | Seat | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Eparchy of Arad | Arad | |

| Eparchy of Bačka | Novi Sad | Bačka |

| Eparchy of Belgrade | Belgrade (Beograd) | (1726–1739) |

| Eparchy of Buda | Szentendre (Sentandreja) | |

| Eparchy of Gornji Karlovac | Karlovac | |

| Eparchy of Kostajnica | Kostajnica | (1713–1771) |

| Eparchy of Lepavina | Lepavina | (1733–1750) |

| Eparchy of Mohács | Mohács (Mohač) | (until 1732) |

| Eparchy of Pakrac | Pakrac | Now Eparchy of Slavonia |

| Eparchy of Râmnicu | Râmnicu Vâlcea (Rimnik) | (1726–1739) |

| Eparchy of Srem | Sremski Karlovci | Syrmia |

| Eparchy of Temišvar | Timișoara (Temišvar) | Banat |

| Eparchy of Valjevo | Valjevo | (1726–1739) |

| Eparchy of Vršac | Vršac | Banat |

| Eparchy of Transilvania | Sibiu (Sibinj) | Spiritual jurisdiction only |

| Eparchy of Bukovina | Chernivtsi (Černovci) | Spiritual jurisdiction only |

| Eparchy of Dalmatia | Šibenik | Spiritual jurisdiction only |

Heads of Serbian Orthodox Church in Habsburg Monarchy, 1690–1848

edit| No. | Primate | Portrait | Personal name | Reign | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arsenije III Арсеније III Arsenius III |

Arsenije Čarnojević Арсеније Чарнојевић |

1690–1706 | Archbishop of Peć and Serbian Patriarch | Leader of the First Serbian Migration | |

| 2 | Isaija I Исаија I Isaias I |

Isaija Đaković Исаија Ђаковић |

1708 | Metropolitan of Krušedol | ||

| 3 | Sofronije Софроније Sophronius |

Sofronije Podgoričanin Софроније Подгоричанин |

1710–1711 | Metropolitan of Krušedol | ||

| 4 | Vikentije I Викентије I Vicentius I |

Vikentije Popović-Hadžilavić Викентије Поповић-Хаџилавић |

1713–1725 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 5 | Mojsije I Мојсије I Moses I |

Mojsije Petrović Мојсије Петровић |

1726–1730 | Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci | ||

| 6 | Vikentije II Викентије II Vicentius II |

Vikentije Jovanović Викентије Јовановић |

1731–1737 | Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci | ||

| 7 | Arsenije IV Арсеније IV Arsenius IV |

Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta Арсеније Јовановић Шакабента |

1737–1748 | Archbishop of Peć and Serbian Patriarch | Leader of the Second Serbian Migration | |

| 8 | Isaija II Исаија II Isaias II |

Isaija Antonović Јован Антоновић |

1748–1749 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 9 | Pavle Павле Paul |

Pavle Nenadović Павле Ненадовић |

1749–1768 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 10 | Jovan Јован John |

Jovan Georgijević Јован Ђорђевић |

1768–1773 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 11 | Vićentije III Вићентије III Vicentius III |

Vićentije Jovanović Vidak Вићентије Јовановић Видак |

1774–1780 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 12 | Mojsije II Мојсије II Moses II |

Mojsije Putnik Мојсије Путник |

1781–1790 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 13 | Stefan I Стефан I Stephen I |

Stefan Stratimirović Стефан Стратимировић |

1790–1836 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 14 | Stefan II Стефан II Stephen II |

Stefan Stanković Стефан Станковић |

1836–1841 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | ||

| 15 | Josif Јосиф Joseph |

Josif Rajačić Јосиф Рајачић |

1842–1848 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | Elevated to Patriarch at the May Assembly |

Timeline

edit

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Ćirković 2004, p. 150-151.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 144, 244.

- ^ Draganić 2010, p. 257.

- ^ a b c Mario Katic, Tomislav Klarin, Mike McDonald: Pilgrimage and Sacred Places in Southeast Europe: History, Religious Tourism and Contemporary Trends, LIT Verlag Münster, Oct 1, 2014 page 207

- ^ Calic, Marie-Janine (2019). The Great Cauldron: A History of Southeastern Europe. Harvard University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9780674983922.

- ^ Todorović 2006, p. 12-13.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 150.

- ^ Dabić 2011, p. 191-208.

- ^ Točanac-Radović 2018, pp. 155–167.

- ^ Todorović 2006, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 165.

- ^ Bojan Aleksov: Religious Dissent Between the Modern and the National: Nazarenes in Hungary and Serbia 1850-1914, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006 page 33

- ^ Aidan Nichols: Theology in the Russian Diaspora: Church, Fathers, Eucharist in Nikolai Afanasʹev (1893–1966), CUP Archive, 1989 page 49

- ^ Augustine Casiday: The Orthodox Christian World, Routledge, Aug 21, 2012 page 135

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 167, 171.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 200-202.

Sources

edit- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.

- Bocşan, Nicolae (2015). "Illyrian privileges and the Romanians from the Banat" (PDF). Banatica. 25: 243–258.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Dabić, Vojin S. (2011). "The Habsburg-Ottoman War of 1716-1718 and Demographic Changes in the War-Afflicted Territories". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 191–208.

- Đorđević, Miloš Z. (2010). "A Background to Serbian Culture and Education in the First Half of the 18th Century according to Serbian Historiographical Sources". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 125–131. ISBN 9783643106117.

- Draganić, Ifigenija (2010). "Greek and Serbian in the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy in the 18th and at the Beginning of the 19th Centuries". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 257–265.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Serbian Orthodox Church". Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 519–520. ISBN 9781438110257.

- Гавриловић, Славко (2006). "Исаија Ђаковић: Архимандрит гргетешки, епископ јенопољски и митрополит крушедолски" (PDF). Зборник Матице српске за историју. 74: 7–35.

- Грујић, Радослав (1929). "Проблеми историје Карловачке митрополије". Гласник Историског друштва у Новом Саду. 2: 53–65, 194–204, 365–379.

- Грујић, Радослав (1931). "Пећки патријарси и карловачки митрополити у 18 веку". Гласник Историског друштва у Новом Саду. 4: 13–34, 224–240.

- Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate: A History of Its Metropolitanates with Annotated Hierarch Catalogs. Wildside Press LLC.

- Martin, Joannes Baptista; Petit, Ludovicus, eds. (1907). "Serborum in Hungaria degentium synodi et constitutiones ecclesiasticae". Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio. Vol. 39. Parisiis: Huberti Welter, Bibliopolae. pp. 497–956.

- Pavlovich, Paul (1989). The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian Heritage Books.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850654773.

- Popović, Radomir V. (2013). Serbian Orthodox Church in History. Belgrade: Academy of Serbian Orthodox Church for Fine Arts and Conservation.

- Puzović, Predrag (2004). "Pavle Nenadović (1699–1768)". 100 most eminent Serbs. Belgrade: Princip. pp. 108–114.

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248. ISBN 9780470766392.

- Radić, Radmila (2015). "The Serbian Orthodox Church in the First World War". The Serbs and the First World War 1914-1918. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. pp. 263–285.

- Schwicker, Johann Heinrich (1881). "Die Vereinigung der serbischen Metropolien von Belgrad und Carlowitz im Jahre 1731". Archiv für österreichische Geschichte. 62: 305–450.

- Šuletić, Nebojša (2021). "Usurpations of and Designated Successions to the Throne in the Serbian Patriarchate: The Case of Patriarch Moses Rajović (1712-24)" (PDF). Balcanica. 52: 47–67.

- Точанац, Исидора Б. (2007). "Београдска и Карловачка митрополија: Процес уједињења (1722-1731)" (PDF). Историјски часопис. 55: 201–217. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- Точанац, Исидора Б. (2008). Српски народно-црквени сабори (1718-1735). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ. ISBN 9788677430689.

- Точанац-Радовић, Исидора Б. (2014). Реформа Српске православне цркве у Хабзбуршкој монархији за време владавине Марије Терезије и Јосифа II (1740-1790). Београд: Филозофски факултет.

- Точанац-Радовић, Исидора Б. (2014). "Настанак и развој институције Српског народно-црквеног сабора у Карловачкој митрополији у 18. веку (The appearance and the development of the institution of Serbian national-clerical council in the Metropolitanate of Karlovci in 18th century)" (PDF). Три века Карловачке митрополије 1713-2013. Сремски Карловци-Нови Сад: Епархија сремска, Филозофски факултет. pp. 127–144.

- Точанац-Радовић, Исидора Б. (2015). "Српски календар верских празника и Терезијанска реформа" (PDF). Зборник Матице српске за историју. 91: 7–38.

- Točanac-Radović, Isidora (2018). "Belgrade - Seat of the Archbishopric and Metropolitanate (1718–1739)". Belgrade 1521-1867. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 155–167.

- Todorović, Jelena (2006). An Orthodox Festival Book in the Habsburg Empire: Zaharija Orfelin's Festive Greeting to Mojsej Putnik (1757). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754656111.

- Вуковић, Сава (1996). Српски јерарси од деветог до двадесетог века (Serbian Hierarchs from the 9th to the 20th Century). Евро, Унирекс, Каленић.

External links

edit- About Metropolitanate of Karlovci (in Serbian)